A Three-Time Memoirist Switches to Narrative Nonfiction

Helene Stapinski on taking a break from a genre she loves, but which often landed her in hot water with family.

It was only a matter of time.

By my mid-50s, I had run out of material as a memoirist. But it had been a good run.

My first book, Five-Finger Discount, recounted growing up in Jersey City in a family of colorful criminals and covered birth to my mid-20s. It became a national bestseller back in 2001, in the early days of the memoir craze. The follow-up, Baby Plays Around, chronicled the years I spent as a drummer in a rock band on the Lower East Side in the 90s and the near breakup of my marriage. My third book, Murder in Matera, traveled a century back in time to document a family murder from Southern Italy—a prequel of sorts to book number one.

I didn’t start out as a memoirist, of course. No one does. You have to live life before you can write about it. I began my career as a newspaper reporter, writing about other people on a daily basis. My first stabs at first person writing came in a weekly column for my hometown newspaper, The Jersey Journal. For Five-Finger Discount, I utilized those same journalistic skills I’d used on others to pick apart my own life. I scrutinized my extended family, doing interviews, digging into newspaper and criminal archives and creating a true-to-life narrative from the facts.

It never occurred to me that Five Finger Discount would ever actually get published, never mind that people would actually read it or that it would become a bestseller. My family and I suffered the consequences of the book’s popularity.

As a young writer at the time, it never occurred to me that the book would ever actually get published, never mind that people would actually read it or that it would become a bestseller. My family and I suffered the consequences of the book’s popularity. My mother nearly had a fist fight with a great aunt in her building lobby (they lived across the street from each other in Jersey City.) My brother had to defend me once at a big dinner where a particularly unmerciful priest called me “that Stapinski broad”—not knowing he was my brother. My sister, an official in the Jersey City public schools, ran the gauntlet between those who loved “her sister’s book” and those who hated it—and me, even though they’d never met me. (Many of those who hated the book, strangely, had refused to read it, offended that I would talk trash about Jersey City.)

But it wasn’t all bad. I used part of my big publishing advance to help bail one cousin I liked out of jail. And paid the tuition of another young relative one semester when her father was out of work and couldn’t afford it.

There were the relatives—not even in the book—who would yell at me. The cousin in Connecticut who called to castigate me for the portrayal of my father in my book. I hung up on her. The cousin—the daughter of the fist-fighting great aunt—who always gave me dirty looks whenever she saw me. And the aunt who wrote letters to the editor of The Jersey Journal, accusing me of making it all up. (Not only did I not make things up, but I left lots of juicy stuff out).

After writing about my faltering marriage in book two, countless people came forward to tell me their secret marriage problems, things they hadn’t even shared with their close family and friends. And book three brought—and still brings—an avalanche of letters from those looking for help in researching their family histories in Italy.

When I ran out of my own material, or rather when the events of my life became not quite fascinating enough to serve up to the rest of the world, I have to say I was kind of relieved. I went back to that old standby, journalism, writing about the lives of others.

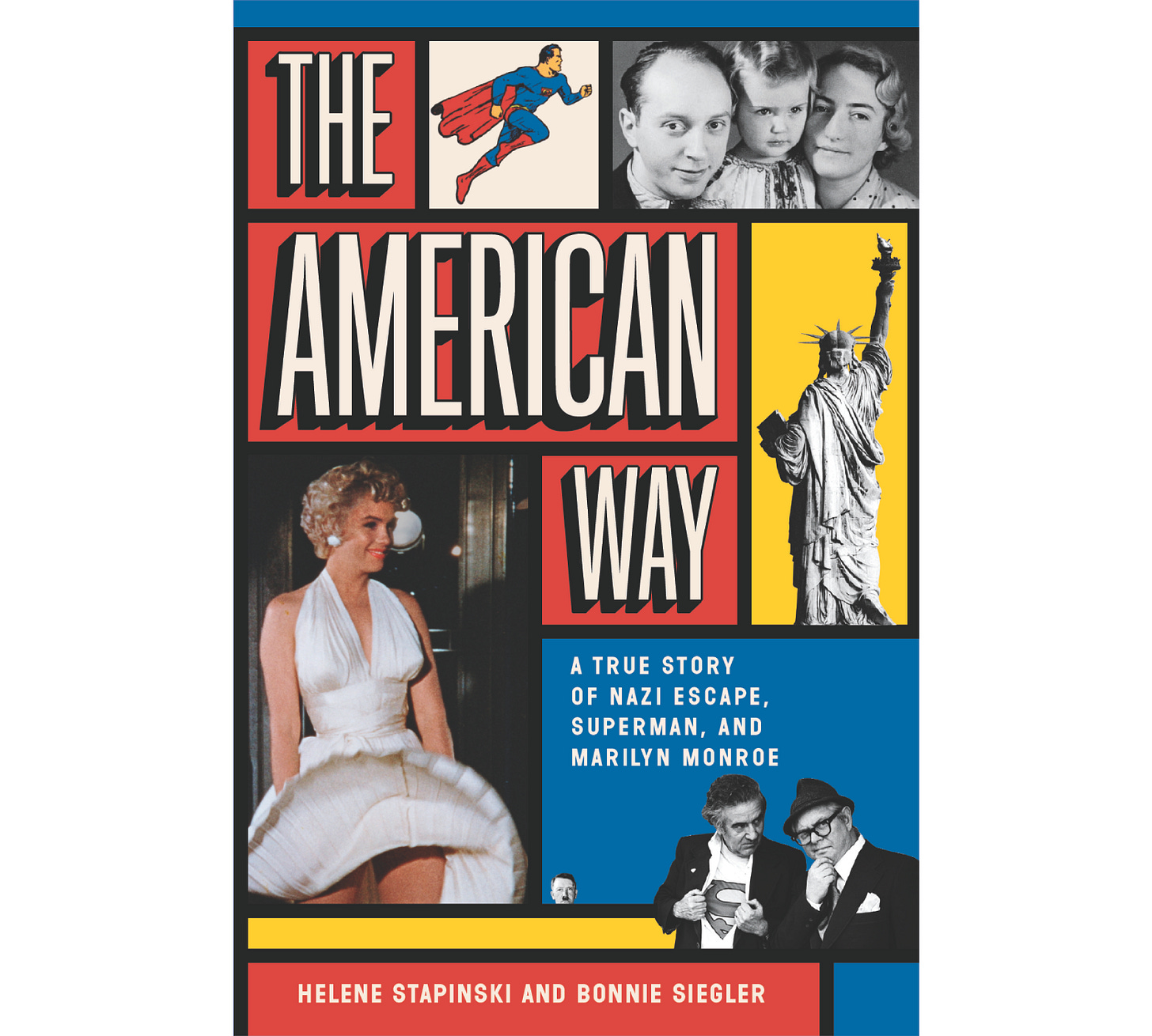

One of those lives was a man named Jules Schulback. Though Jules was dead, his granddaughter, Bonnie Siegler, had found footage he had shot of Marilyn Monroe back in 1954. While cleaning out her grandfather’s Manhattan apartment, she found home movies, which he had always bragged about, of Marilyn’s dress blowing up on the subway grate on Lexington Avenue. I interviewed her for a story on Jules’ film. But the movie footage was the least of the excitement in his life.

I went back to that old standby, journalism, writing about the lives of others. One of those lives was a man named Jules Schulback. Though Jules was dead, his granddaughter, Bonnie Siegler, had found footage he had shot of Marilyn Monroe back in 1954.

Jules had escaped from Nazi Germany in 1938. His story, like the stories of all those who survived and those who didn’t, was an incredibly emotional, sometimes sorrowful nail-biting narrative. After my story about Jules and Marilyn ran in The New York Times, Bonnie and I became fast friends. Eventually, she asked if I would be interested in writing a book about him with her help. She would do lots of the research and I would do the writing.

I came to Bonnie with three decades of family writing wisdom. I warned her early on that some relatives might not be happy about the result of her digging, that the ones who would launch an attack were always the ones you least expected. But in order for the book to be good, it had to be true, no punches pulled. The good with the bad. That readers can smell it when you‘re holding back. And she agreed.

Bonnie, who runs her own graphic design firm, dove head-first into her research. She contacted the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC and found things about her relatives that no one in her family had ever known. The Nazis kept incredibly detailed records and so we were able to recreate what happened to those relatives that Jules had left behind in Berlin in 1938. They became characters in our story: Bonnie’s Aunt Golda, who survived four concentration camps, and her great grandparents, who were murdered in a gas van on a highway outside of Minsk.

Bonnie and I would talk more than a dozen times a day, sometimes to exchange information, sometimes to commiserate on the evil of the Nazis, and sometimes just to console each other. Bonnie and her family weren’t my family, but they had become my mishpucha—the Yiddish word for “almost family.” (I also learned a lot of Yiddish in the two years we worked together.)

The Nazis kept incredibly detailed records and so we were able to recreate what happened to those relatives that Jules had left behind in Berlin in 1938. They became characters in our story.

To fill in the narrative blanks, and to make Jules a living, breathing character, Bonnie raided her mother’s photo and memento collection. She dug up old letters. Her mother was two years old when they escaped Berlin. And though she had no memories of Germany, she and her husband had plenty of memories of Jules. I visited her parents on Long Island and did countless interviews with them about Jules and other relatives. Bonnie also contacted practically every member of her extended family and set up interviews. Since this all happened over the pandemic, they were mostly conducted over Zoom.

Even though I was raised Catholic, Bonnie’s family brought me into the fold, readily adopted me, and shared everything they could. One of the twists of the story (spoiler alert) is that Jules’ sponsor to come over to America was a man named Harry Donenfeld, the original publisher of DC Comics—and Superman. We tracked down Harry’s relatives and interviewed them, too. They invited us over and shared their family photos as well.

It’s been a relief not to have to walk through the minefield of my own family’s reactions to my latest book.

When the book was finished, I suggested we send advance copies to the closest members of the family—which I had always done—and those who had gone above and beyond to help us, not only to thank them, but to correct any errors. Except for a few small factual mistakes, which have all been corrected, it’s been a smooth ride so far. No one has called Bonnie to yell at her. Not yet, anyway.

It’s been a relief not to have to walk through the minefield of my own family’s reactions to my latest book. But I’m there for Bonnie if and when anyone attacks her. I tell her, whatever they’re mad about, just blame me.