Bargaining For My Life in 'The Sanctuary of the Woods'

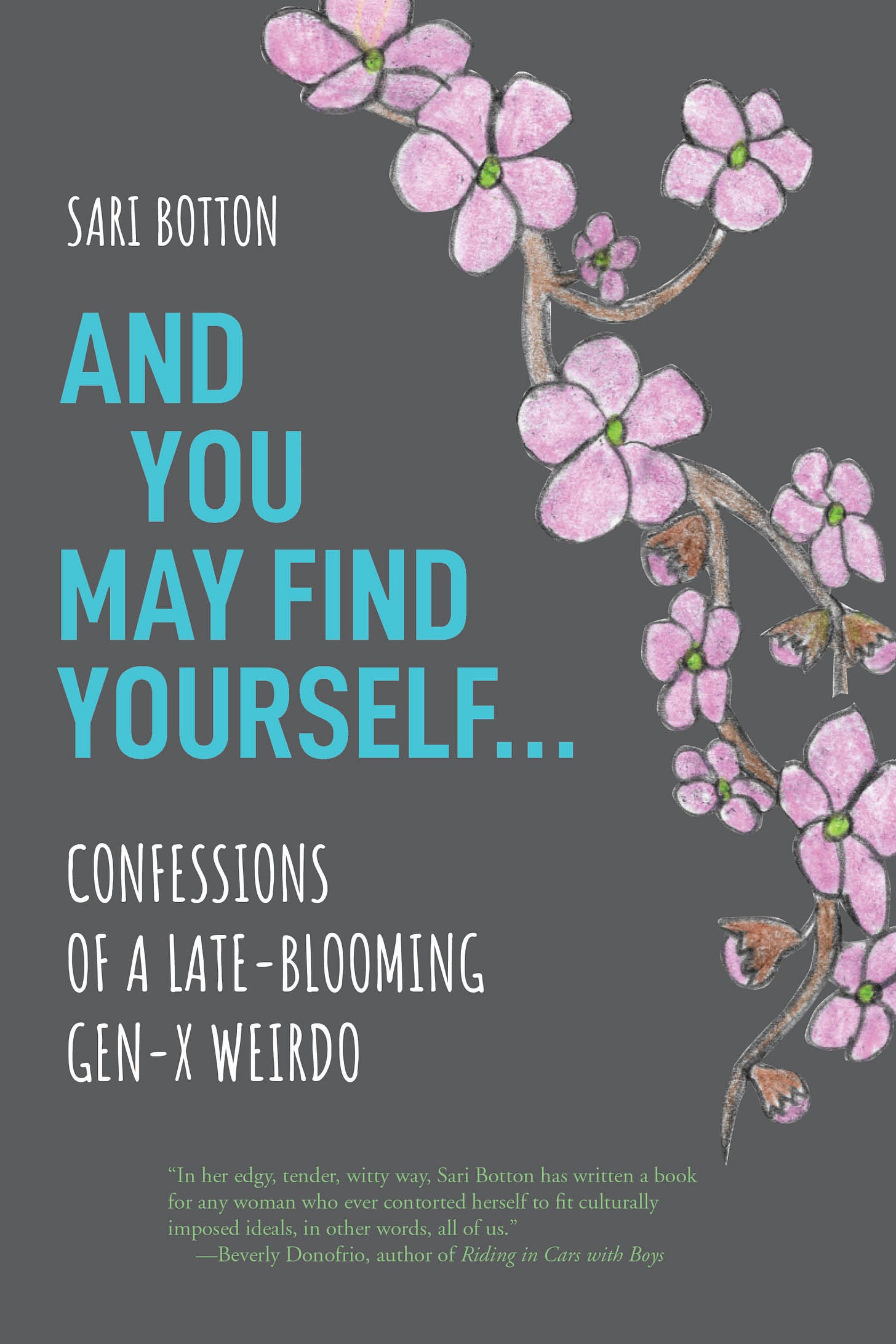

"It would be many years before I realized that no one was punishing me but me." An excerpt of "And You May Find Yourself..."—a memoir by Sari Botton.

This is the fourth essay in the First Person Singular series from Memoir Monday. Usually these essays are paywalled, but this one is for everyone, paid and free subscribers alike.

It was a big deal when I told my two sets of parents that on Yom Kippur, instead of attending either of their two synagogues, I’d be hiking and camping in “the sanctuary of the woods.” It was the fall of 1999, and I was turning 34—certainly old enough to make my own decisions with regard to religious observance. My parents weren’t too happy about it. They thought I was “rebelling,” but that wasn’t at all the case. It wasn’t something I was doing to them, it was something I was doing for me.

From the time I was 11 I’d had issues with the divisions religion could cause, and all the violence committed in the name of god. I’d recoiled in Hebrew school when teachers would express anti-Palestinian sentiments, and was told that to question or challenge that was to be a self-hating Jew. But it sounded to me like bigotry, and didn’t jibe with the golden rule or other tenets of Judaism I’d been taught. Also, as with just about all religions, there were sexist aspects to Jewish law that sat at odds with my nascent feminism. In my mid-thirties, it felt like high time I retreat from this thing that had troubled me, and was so deeply enmeshed through every layer of my existence that I couldn’t get any perspective on it.

Calling the Adirondacks “the sanctuary of the woods” was spin, not just for them, but for me. I half-believed myself when I said that the object of my trip was some sort of spiritual communing with nature to soothe my troubled soul. At a deep level, though, I knew there was going to be nothing soothing about this weekend adventure. I was going with Tim, an emotionally unreachable man ripped straight from the pages of Pam Houston’s Cowboys Are My Weakness, whom I’d been seeing on and off for close to three years. And we were hanging by a thread.

I half-believed myself when I said that the object of my trip was some sort of spiritual communing with nature to soothe my troubled soul. At a deep level, though, I knew there was going to be nothing soothing about this weekend adventure. I was going with Tim…

Two-and-a-half years before, in January of 1997, a few months after I’d turned 31, Tim appeared as if out of nowhere. The night I met him, I almost hadn’t gone out. A jazz singer I liked and hoped to interview for a profile was performing at a bar called Arlene’s Grocery on the Lower East Side. But I was feeling down, and resistant to braving the cold. I knew some of why I felt down was that in the midst of a six-month dry spell in my dating life, I was lonely; ironically, in winter, when you most need to seek out others’ company, you are least inclined to leave the house to do so. Somehow, as if some external force was leading me, I pushed myself out the door.

Tim and I were the only two people in the audience. It was a wintry weeknight, and the clientele at Arlene’s tended to be more into rock than jazz. I’d spotted him when I walked in—a slight guy in worn chinos and a plaid shirt, his shaggy brown hair framing a striking, chiseled face. “He’s like a brunette Gary from thirtysomething,” I would tell a friend the next day. I was seated at a table far from his, and minutes after I felt his piercing blue eyes on me, he moved in my direction with his half-finished pint.

The main reason I ventured out that night was to meet the singer and set up an interview. But once male attention was on the table, I forgot my intentions. I also forgot my manners, largely ignoring the singer I’d come to hear as I joined Tim in conversation.

Tim had the gift of gab, peppering me with questions and telling me all about himself, at a mile a minute. He was a science teacher, he told me. When I said I was a writer, he started talking books—turned out he was a reader, too. Not bad, I thought. He talked in a hyper-animated way that struck me as slightly off, as if he’d just emerged from the desert and hadn’t spoken to another human in years. He seemed like one of those New York City lonely people, who despite being surrounded, wall-to-wall, by humans, rarely interacted with them. Why on earth does this cute, smart guy seem so intensely lonely? I wondered. Only in hindsight would I recognize it as a red flag.

He talked in a hyper-animated way that struck me as slightly off, as if he’d just emerged from the desert and hadn’t spoken to another human in years. He seemed like one of those New York City lonely people, who despite being surrounded, wall-to-wall, by humans, rarely interacted with them.

“Have you read the English Patient?” he asked. I hadn’t. He had, and was planning to see the movie that weekend. “Would you like to join me?”

Before the movie he made me dinner at his place, a crammed, claustrophobic two-room studio in a run-down tenement on the Lower East Side. Another red flag: Tim owned only one plate. We shared it that first night, and many others, after that.

***

Having been on a few prior hiking and camping trips with Tim, I knew that this one, to the Adirondacks, would be challenging. It had become an established part of the deal that these endeavors were always at a level way more difficult for me than for him. These were Tim’s adventures. I was always “welcome to join” him, even though we traveled in my car. In the fall of 1997, we’d camped in a different area of the Adirondacks, and in 1998, we’d spent a weekend backpacking through three Catskill peaks.

The last day of that Catskills trip, we descended in a major thunderstorm, and the path was treacherous. As we approached the last quarter mile of our hike out, I slipped on a wet tree root and pitched forward, my 25-pound backpack intensifying the impact when my forehead made contact with stone. The pain was instant, but it was mitigated significantly by how concerned Tim seemed. Tired of being patient with my slower pace, he’d gotten a bit ahead of me. But when he heard me fall and scream, he came running back.

It had become an established part of the deal that these endeavors were always at a level way more difficult for me than for him. These were Tim’s adventures. I was always “welcome to join” him, even though we traveled in my car.

“Are you okay?” he asked, helping me up, then embracing me more warmly than he ever had before. I’d been trying not to cry, but the hug cracked me open. I melted into him, enjoying a taste of what I’d been holding on for, all that time. (Some feminist I was.) When we got to the nearby cabin we were staying in, he tended to the egg-sized welt on my head with ice, and was tender toward me.

***

This trip, there was an added danger factor: the week leading up to our outing, a major hurricane had ripped through the Northeast. I caught something on the news, then read in the paper about how it had devastated many Adirondack trails. There’d been mudslides, and many trees were down, blocking major paths. I assumed we would be canceling our plan.

“Are you kidding?” Tim said. “This is great news. It means fewer other people will go. We’ll have our pick of campsites!”

As the owner of the car we’d be using, I should have realized I had the power to shut our plan down. Or I could have loaned Tim my car, and let him go by himself, which he likely would have preferred. But things between us had been so rocky, I was afraid to make waves. He’d recently broken up with me for the fourth time in less than three years. Shortly afterward, he’d returned to me, and I took him back, more desperately than I ever had before, even though I was fully aware of how miserable I was with him. I was in a low place, self-esteem-wise, and work-wise—I’d been bullied by a misogynist boss into quitting my last job.

As soon as Tim was finished with work that Friday, we jumped in the car. The plan was to spend the first night at the home of his friends upstate, then leave early Saturday for “the ‘Dacks” as Tim and the other initiated outdoorspeople called them. As soon as we arrived, his friend voiced his concern. “You’re still going, even though the hurricane has made a mess up there?” he asked. “I’ve heard some of the trails are completely washed out. You might want to cancel your trip, buddy.”

This trip, there was an added danger factor: the week leading up to our outing, a major hurricane had ripped through the Northeast…There’d been mudslides, and many trees were down, blocking major paths. I assumed we would be canceling our plan.

I took a breath and looked to Tim, hoping he would be able to recognize a voice of reason when it was coming from someone other than me. Please cancel, I thought. Please cancel. Please cancel. Please cancel. Please cancel. Please cancel… It became a mantra in my head for the long 20 seconds it took him to respond.

“No way,” Tim said, with a devilish laugh. “This is going to be the best. We’ll be the only ones. We’ll have it all to ourselves.”

Great, I thought. There’d be no one around if anything bad happened, no one to alert rescuers if we got hurt. I still could have shut the whole thing down, or taken a bus back to the city, letting Tim take my car on his own. That I didn’t is a testament to how desperate I felt, how much power I’d given Tim, how oblivious to my own power I was.

***

I’ve read that addiction is established through intermittent gratification. When you’ve been gratified by something or someone, and then the source of that gratification is withdrawn, you naturally become consumed with recapturing it.

Tim and I had interlocking addictions: he chased the fleeting gratification of being numbed by booze, cigarettes, and weed. I chased the fleeting gratification of getting Tim’s attention in the rare moments he wasn’t completely numbed out—or pushing me away. I lived for whatever crumbs I could get from him, any vague expression of affection. Although, increasingly the only attention he gave me was snide criticism, couched as good natured teasing.

Tim and I had interlocking addictions: he chased the fleeting gratification of being numbed by booze, cigarettes, and weed. I chased the fleeting gratification of getting Tim’s attention in the rare moments he wasn’t completely numbed out—or pushing me away.

Tim seemed incapable of drawing me close without also counteracting that in some way, to create distance. Every kind gesture was tempered with a broken promise—he wouldn’t call or show up when he’d said he would—or an off-putting “joke” about the shape of my body, petite with a more than ample behind. When we began hiking together the first year we dated, he came up with another term for my backside: he called it my “third foot,” because often, when descending frighteningly steep passages, I would resort to sitting and sliding at least part of the way down on my butt. “Are you just gonna hike the whole way down on your third foot?” he’d ask, dismissively.

“Frighteningly steep” was pretty much the default setting for the hiking Tim and I did together, most of it far out of my league—and far outside the realm of what I would have chosen to do with my time if I weren’t trying to seem like the kind of person Tim would choose. I am uncommonly clumsy. Prior to meeting Tim, I’d only engaged in hiking so tame, at so little of an incline, that it was hard to distinguish it from plain walking. I’d been to Harriman State Park with a prior boyfriend, and again with some friends, but only on short trails with the lowest grades of elevation. I’d been on short hikes up something called “Rattlesnake Hill” with a writing mentor who lived in the Adirondacks, but it was, in fact, a hill. I thought that was what hiking meant.

I’d also never camped out overnight before, despite having attended sleep-away camp. Every year, the nature counselor would bring each age group into the woods with tents and sleeping bags, and I was always glad that my being cast in musicals, which rehearsed on those nights, rendered me exempt. Back in my bunk, I’d count my blessings that I wasn’t sleeping on the ground, fighting off insects, snakes, and wildlife.

Don’t get me wrong—I enjoyed being out in nature, preferably at the beach, where I grew up. I also enjoyed being in the woods, although preferably under less death-defying conditions. Years later, I’d move upstate and happily hike up and down a small mountain in town most mornings—but I’d steer clear of the steep, unwieldy scrambles over boulders in nearby mountain ranges, even though they were much easier than the scrambles over boulders in the high peaks that I’d agonize through with Tim. At my mom’s apartment, I spent many summer nights sleeping out under the stars, on a chaise lounge on her small terrace overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. But I was no one’s idea of an outdoorswoman. Certainly not Tim’s idea of one. I was merely who was around, and I had wheels, so I was “welcome” along.

When I told my parents that for my birthday I wanted money so that I could stock up on outdoor gear, they looked at me as if I had grown a second head. In fact, I’d grown a whole new persona, “Outdoorsy Sari” a rugged, unfussy, low-maintenance version of myself who nearly got Regular Sari killed.

That vague offer was all it took for me to make a beeline to Paragon and Campmoor in search of serious hiking boots, a sleeping bag and mat, a backpack, polypropylene and fleece clothing, and other outdoor gear. The first year I was dating Tim, when I told my parents that for my birthday I wanted money instead of any other gift so that I could stock up on gear, they looked at me as if I had grown a second head. In fact, I’d grown a whole new persona. Like that, “Outdoorsy Sari” was born—a rugged, unfussy, low-maintenance version of myself I very much wanted to believe was real. She not only eclipsed Regular Sari for a few years; she nearly got Regular Sari killed.

***

I didn’t invent Outdoorsy Sari, or go hiking and camping, solely for Tim’s benefit. I also wanted to see myself in a more rugged light. Like Ralph Lauren (nee Lifschitz), and so many other Jews before me, I wanted to be accepted into a cool, anti-chic milieu I’d never been exposed to in my suburban Jewish world.

When I heard my WASPy writing mentor, or Tim, toss off names of Adirondack and Catskill peaks they’d “bagged,” I wanted to speak their vernacular. I wanted entrée into their club. I felt like the stereotypical clumsy, fearful, frail, pale Jewess, and I eagerly wanted to transcend that. See, I didn’t just become Outdoorsy Sari because I aspired to be with Tim; to a degree, I aspired to be with Tim so that I could become Outdoorsy Sari.

Once I began hiking and camping with Tim, I took pride in casually tossing off the names of the peaks I’d “bagged,” too (for the record, I’ve got six peaks in the Adirondacks, and five in the Catskills), along with naming from rote the various kinds and brands of gear. It made me feel tough and sexy in a one-of-the-boys way that had previously seemed off-limits to me.

I didn’t invent Outdoorsy Sari, or go hiking and camping, solely for Tim’s benefit. I also wanted to see myself in a more rugged light. Like Ralph Lauren (nee Lifschitz), and so many other Jews before me, I wanted to be accepted into a cool, anti-chic milieu I’d never been exposed to in my suburban Jewish world.

I’ll admit that I also learned a lot on those adventures, and grew from them, in ways. I discovered I was much more agile and capable than I’d previously known myself to be. I figured out how to get through the hardest stretches by staying in the moment and simply putting one foot in front of the other. At the end of each backpacking trip, I felt surprisingly strong, accomplished, empowered. Still, I didn’t so much enjoy those times in the woods with Tim as I endured them.

I always approached adventures with Tim with a mix of excitement and dread, a balance that had shifted more toward dread the longer we were together. A nice thing about hiking and camping with him was that it usually occurred when he was going through a dry period, drinking-wise. Tim wasn’t a falling-down drunk like another man I’d dated; he was a mean drunk, though, throwing out nasty quips about whoever was around him, which was often only me. (Mystery solved: this was why he was lonely.) That’s not to say that when he wasn’t drinking he was exactly nice. He was still rarely warm, but at least his nastiness in those sober times was tempered.

The dread I experienced before camping trips with Tim was about wondering whether the person sharing a tent with me would be relatively kind, and also about my fears as a newbie hiker traveling with someone much more experienced and naturally athletic than me. Tim was never willing to alter our course to take into consideration my level of ability, or lack thereof.

I figured out how to get through the hardest stretches by staying in the moment and simply putting one foot in front of the other. At the end of each backpacking trip, I felt surprisingly strong, accomplished, empowered. Still, I didn’t so much enjoy those times in the woods with Tim as I endured them.

I also wasn’t keen on sleeping out in the cold. Even on unseasonably warm fall days, the temperature in the mountains would drop drastically after sundown. The only good thing about that was it meant Tim would most likely be especially snuggly in our tent. Oh, the irony of me shivering through the night, sometimes even risking frostbite, for just a little bit of warmth from a cold man.

~

The ground was soaking wet when we arrived in the area of the Adirondacks where we would be hiking and camping, and the sky threatened more rain. We parked the car and hiked a marshy path until the sky opened up. Fortunately there was a big lean-to nearby, and we made a beeline for it. There was a park ranger there, and he was surprised to see us.

“You sure you’re up for hiking in this?” he asked, gesturing to the area around us. “This place got hit pretty hard by the hurricane. Lots of trees down, and it’s pretty slippery.”

In my head, I thought: Please listen to the ranger. Let’s turn around and go home. But I couldn’t find the courage to say those words out loud.

“No, we’re good,” Tim said, and my stomach grew a knot.

***

When the rain let up, we set out again. I took a deep breath, and went into being-in-the-moment mode, negotiating one step at a time. We’d be taking the Gothics Loop Trail over three peaks, one per day—Upper Wolf Jaw, Armstrong, and Gothics—setting up camp in a different spot each night.

As we began to ascend Upper Wolf Jaw, I slipped on a wet tree root, falling in such a way that I badly bruised my left shin. I cried on impact, as I tend to. Tim was a bit ahead of me, and I called out to him. “Tim, I fell!” When he didn’t respond, I called again, this time with more alarm in my voice. I was so afraid he’d gotten far enough away to lose me. I had a shitty Nokia cell phone, but there was no cell service. I called out a third time, “Tim, I fell, and I’m scared! Where are you?” Now I was crying hysterically. Three minutes later, Tim was running toward me. I was on the ground, my heavy pack by my side, holding my shin.

“What’s the problem?” he asked, coldly.

“I fell, and I hurt my shin, and I’m so scared. I don’t know if this is safe.”

The closer we got to the top, the scarier it became. The mountain was literally bald. And steep. The terrain was like nothing I’d ever seen before—like being on another planet. For much of the way, there was nothing to grab onto. At a certain point, I had to stop standing upright because I was sure I was going to fall to my death. If I sneezed and lost my balance, that was it.

That’s when Tim lost it. He began jumping up and down and screaming, “This is joyful for me! Why can’t you be joyful!” He sounded anything but joyful, by the way. He sounded like an overgrown toddler having a tantrum.

This set the tone for the rest of the weekend. Tim was annoyed by my presence, by the sound of my voice, by my every need, by the difference in our abilities. Whether we were hiking or cooking or setting up camp or sleeping, he gave me the silent treatment. I followed him quietly from place-to-place, counting the hours, looking forward to our three-day trip being over. With the ground still saturated, it was slippery and dicey at every turn. And I was terrified by what I’d been told about the third peak we’d be ascending, Gothics, which was bald at the top.

***

I woke up in a panic the third morning, knowing that Gothics Mountain was ahead of me. It was either go over that dreaded peak, or go in reverse, back over the other two peaks we’d already perilously ascended and descended, and there wasn’t enough time for that. I had no choice but to face the challenge.

The closer we got to the top, the scarier it became. The mountain was literally bald. And steep. The terrain was like nothing I’d ever seen before—like being on another planet. For much of the way, there was nothing to grab onto. At a certain point, I had to stop standing upright because I was sure I was going to fall to my death. If I sneezed and lost my balance, that was it.

I got down on my hands and knees and prayed. That’s right; on Yom Kippur I prayed to the god I wasn’t sure existed, the one I’d left behind in synagogue. I prayed and bargained for my life. What did I need to do to get myself inscribed in the Book of Life? To survive “bagging” this peak? Was god punishing me for not attending synagogue? For having issues with religion? For leaving my suburban first marriage for a less conventional life? It would be many years before I realized that no one was punishing me but me.

Tim had gone ahead—way ahead—again. I was all alone with a heavy pack on my back, and in a state of terror. When I got a little further up, I was happy to spot a cable affixed to the mountain face, which I could grab onto and use to pull myself to the top.

I got down on my hands and knees and prayed. That’s right; on Yom Kippur I prayed to the god I wasn’t sure existed, the one I’d left behind in synagogue. I prayed and bargained for my life. What did I need to do to get myself inscribed in the Book of Life? To survive “bagging” this peak?

When I finally got there, Tim was waiting for me. “You made it,” he said. “You didn’t know you could do that, did you?” He was a bit warmer, but not by much. We stopped long enough to eat lunch. Then we descended, made it to the parking lot, and drove the five hours back to the city, mostly in silence.

***

It was in this painful phase of my relationship with Tim that I made a fateful phone call. To a 1-900-phone-psychic.

I’ve done a lot of embarrassing things in my life, and calling a phone psychic is right up there at the top of the list. I’ve also handed over my hard-earned cash to more than my share of in-person psychics, witches, astrologers, carvers of “magical” candles, and other practitioners of the esoteric arts—which, I’ll admit, is a little weird for a person who rejects religion on the grounds that, among other issues, it seems like a bunch of unfounded hocus pocus. But there’s something extra sketchy and dubious about a pay-per-minute seer you find through a late-night infomercial while watching thirtysomething reruns, when you can’t sleep because your whole life is out of whack.

When I made the call—not my first, mind you—I knew it was a sad and desperate act, but I felt pretty sad and desperate, and didn’t have much shame left. It was the late ’90s, and I was kind of a mess. In my mid-thirties, I was struggling to find enough freelance writing work after a traumatic ending to my last job. I was divorced and single, and I was convinced that was inherently bad. Like most of my generation, I’d been raised in a culture that centered marriage, which turned my struggle to find the one before I aged out of the possibility of childbearing into the central problem of my existence.

Looking back at who I was choosing in those days, it occurs to me that maybe I didn’t really want to settle down just yet. Otherwise, what was I doing dating one emotionally unavailable, non-committal, temperamental man after another? At that early stage in my becoming a feminist, I think on some level I only knew how to maintain a level of independence with men who were even more resistant to commitment than I was. Whatever it was I was doing, at the time, I couldn’t figure it out. All I knew was that the men I was going out with were withholding and difficult to hang onto, and that for some inexplicable reason I wanted to hang onto them. Instead of seeing their inconsistent responses to me as a sign that I should look for someone actually available and interested, I believed it was a problem I could solve by becoming someone else—someone they would more likely be interested in.

I’ve done a lot of embarrassing things in my life, and calling a phone psychic is right up there at the top of the list.

Oh, how many ways I’ve repackaged myself to appeal to different men! I’m not sure where I learned it, but being something of a chameleon in relationships had actually been my standard modus operandi long before I transformed myself into Outdoorsy Sari for Tim and other men—from the time I started interacting with boys as a tween. When my junior high crush told me he hated the color green—one of my favorite colors—I lied and said I hated it too, then promptly threw my favorite green gingham shirt in the garbage. When my first husband and subsequent men in my life wanted to take me skiing, instead of saying, “I’m sorry, but skiing terrifies me and also I’ve tried it enough times to know I don’t like it,” I went along and endured miserable, cold hours upon hours in beginner school.

***

It’s a wonder I made the call that night, after prior calls to the 1-900 number had been so disappointing—usually women “psychics” on the other end with exaggerated, seemingly fake southern or mid-western accents, throwing out wild guesses about my future based on whatever information I gave them. I’d try to bend my mind to believe what they were saying could be real, but it was always a stretch, and always a letdown. After each reading—and after seeing the charges on my credit card—I’d swear off 1-900 calls forever.

But then, after three miserable years on-and-off with Tim, I arrived at a dark, lonely place. I felt hopeless about the future not only with him, but in general. I didn’t have a therapist—couldn’t afford one, and even if I could, I was too emotionally exhausted to consider unspooling my whole backstory again for a new one—and didn’t want my friends and family to know how sad and lonely I was. So I picked up the phone and dialed.

This time a man answered. “How can I help you this evening?”

“Well,” I said, “I wonder if you see things working out between me and this guy I’m dating. Or, if I end it, whether you see someone else on the horizon for me.”

Looking back at who I was choosing in those days, it occurs to me that maybe I didn’t really want to settle down just yet. Otherwise, what was I doing dating one emotionally unavailable, non-committal, temperamental man after another?

“I’m hearing you say you’re thinking of ending things with him,” he said. “What’s that about?” I recognized this as the psychological “mirroring” prior therapists had engaged in with me. Was this guy a psychic or a shrink?

“I kind of want to break up with him,” I admitted. “I mean, it’s definitely not working out. But what if I give up, before I’ve tried everything? Or, what if I give up and don’t find anyone else? Or—what if I do find someone else, but run into the same problems? Maybe all relationships are hard. Maybe all guys are bad, and every single one that I meet won’t be attentive or kind enough. Maybe I should just make it work with this guy. I don’t know...”

I told him about the backpacking trip we’d just returned from—about all the backpacking trips—and about how, every time I was sure Tim just didn’t like me, and it was over, he’d suddenly be warm and attentive. But it never lasted.

“Okay, I’m going to share with you my key to relationships,” the phone psychic said. “Get a pen and paper, because I think you should write this down.”

I grabbed a pen and paper.

“It’s really simple, but a lot of people don’t realize it. You ready?”

I was.

“Okay. Here it is: Not everyone is going to ‘get’ you. Not everyone is supposed to get you. That’s just how it is. When you’re interested in someone and not getting back what you’re giving, stop for a minute and say to yourself, ‘Well, this person just doesn’t get me. And that’s okay.’ And then just let them go, so you can find someone who does get you. It’s the only way to find a person you can be happy with. Someone you get, who gets you.”

It sounded ridiculously simple.

“That’s it?” I said.

“That’s it.”

“Okay, I’m going to share with you my key to relationships,” the phone psychic said. “Get a pen and paper, because I think you should write this down.”

I thought for a second about what he’d said, and realized that as simple as it sounded, the concept was also utterly foreign to me. Recalibrating myself to appeal to someone who had the power to choose or reject me was all I knew how to do in relationships.

“Write these words down,” he said, “and put them somewhere that you’ll see them: ‘Not everyone is going to get me, and that is okay. Not everyone is supposed to get me. When someone shows that they don’t get me, I accept it, then move on to free myself up for someone who will.’’’

As I wrote the words down, even though on a fundamental level they made so much sense, I found I had to fight my resistance to them. I put the piece of paper in my top desk drawer, where I could easily see it. To my surprise, the more I read those words, the more they sunk in.

Still, it would take me a long time to fully integrate the concept. I still need to remind myself of it today, when I meet new people and friendships don’t quite take off. My initial instinct is to try and become someone else, a version of me they’d likely prefer, at least in my mind. Then I think of my conversation with the 1-900-phone-psychic—my last of those—and remember to just be myself and let the cards fall where they may. Not every potential friend will get me. And that’s okay. Not everyone is supposed to get me. (I also stop and wonder each time, whether the man I spoke with was disgraced journalist Stephen Glass, who admitted to falsifying most of his Harper’s story about working for a 1-900-phone-psychic outfit in the late 90s.)

***

It would take a few more months after the weekend in the Adirondacks before I found the nerve to say goodbye to Tim. I thought I’d never hear from him again, but then, years later, he reached out a few times. In each interaction, he exhibited signs of what appeared, unquestionably, to be mental illness—not new behaviors, but old ones, now more exaggerated and obvious. Or, who knows, maybe exactly the same as before, except I can see more clearly now.

Over lunch one day, Tim mused aloud, “I wonder why I pushed so-and-so away,” and also so-and-so, and so-and-so. “Why do I push people away?” The unasked but implied additional question was why did he push me away, again and again, most perplexingly almost immediately after he drew me in close.

Over lunch one day, he mused aloud, “I wonder why I pushed so-and-so away,” and also so-and-so, and so-and-so. “Why do I push people away?” The unasked but implied additional question was why did he push me away, again and again, most perplexingly almost immediately after he drew me in close. Now I know the answer: the guy is unwell. Pushing people away is what he does. He wasn’t just doing it to me. (Perhaps that’s why he had in his possession only one dinner plate?) The whole time, I’d been taking someone else’s fucked up psychology personally, and tailoring a version of myself to accommodate it.

A lot of other questions went unasked over lunch that day. Tim was utterly incurious about my life, my work, my marriage. It was a relief not to really care, or to have even the slightest inkling that I should try to change that.