The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #90: Rich Benjamin

"This story, this book, had been demanding to be written ever since my family—my mother, especially—refused to discuss their past. This book is a restitution of my family’s story."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

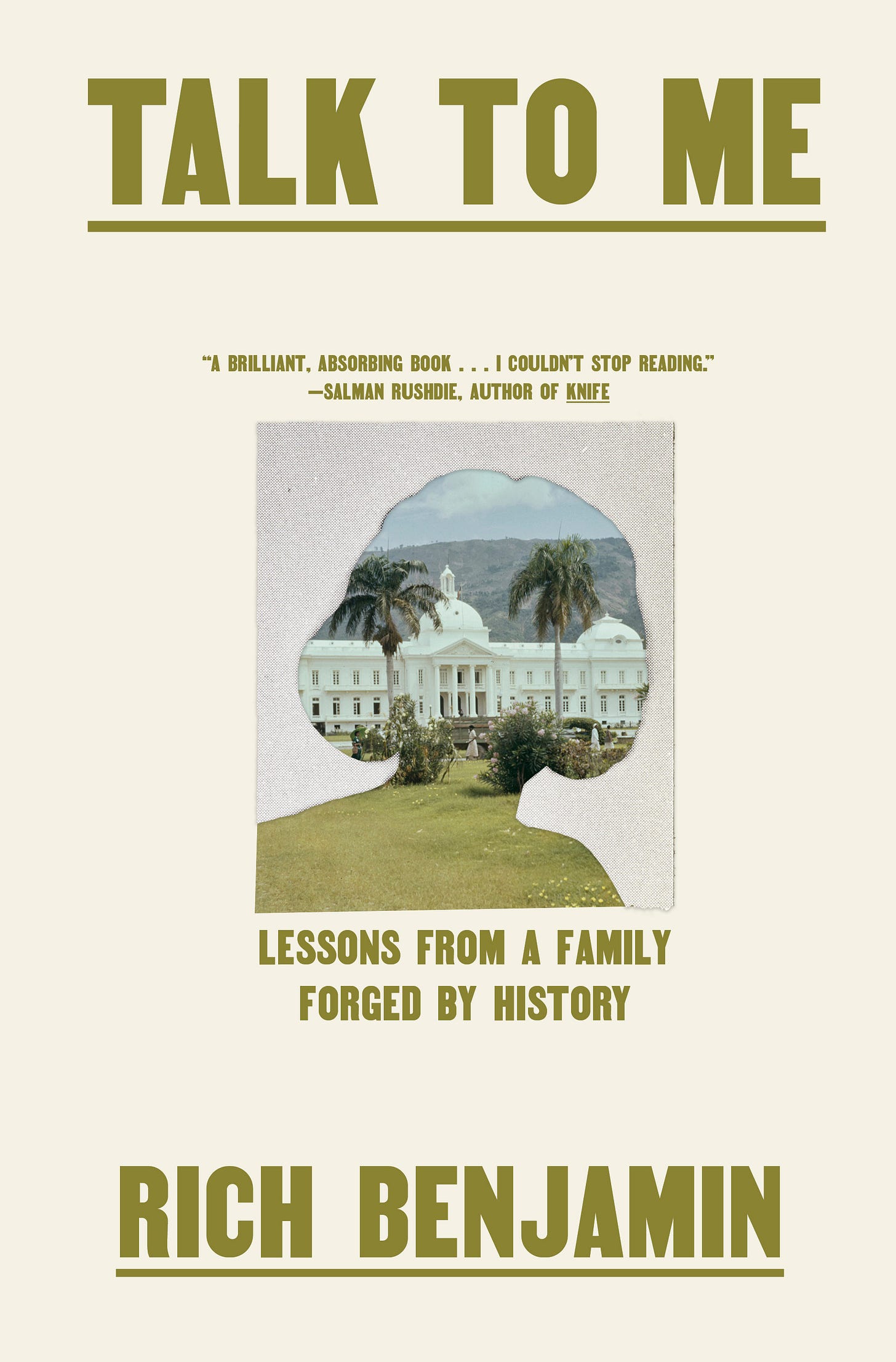

Here’s the 90th installment, featuring Rich Benjamin, author of Talk to Me: Lessons from a Family Forged by History. -Sari Botton

P.S. Check out all the interviews in The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire series.

RICH BENJAMIN is the author of Talk to Me: Lessons from a Family Forged by History, a newly-released family memoir. Benjamin’s first book, Searching for Whitopia: An Improbable Journey to the Heart of White America (2009), was selected for an Editor’s Choice award from the American Library Association. Now in its second printing, this groundbreaking anthropological study is one of the first to have illuminated in advance the rise of white anxiety, white nationalism, and what would become Trumpism, in current US life. Benjamin’s writing appears in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and elsewhere, and he’s interviewed often in the international and US media, including on NPR, MSNBC, and PBS.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I have been writing since I was 8 years old. Now, I am age-queer. Numbers are so hard and normative and settled. Even, odd. Small, big. So binary. I don’t have an age. I am age-nonbinary.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Talk to Me: Lessons From a Family Forged by History, published February 11th, 2025.

What number book is this for you?

Second. My first was Searching for Whitopia: An Improbable Journey to the Heart of White America, published in 2009.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

Talk to Me is a family memoir, a work of creative nonfiction, which blends archival research, oral history, political analysis, and lyricism.

What’s the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Talk to Me is a memoir tracing the fall-out in my family as a result of the CIA-backed coup that ended my grandfather’s presidency of Haiti in 1957, the secrecy that shrouded that catastrophe within my family, and how these events rippled into my own life, coming of age in Reagan’s America. Talk to Me weaves large scale espionage history with intimate stories of individual family members: grandfather, mother, me.

In this book, I don’t paint just the portrait of my family, but a bold, pugnacious portrait of America—of the human cost of the country’s hostilities abroad, the experience of migrants on these shores, and how the indelible ties of family endure through triumph and loss, from generation to generation. And so, Talk to Me also is an original portrait of a family’s hope and resilience in America from the Cold War to Trumpism.

Talk to Me is a memoir tracing the fall-out in my family as a result of the CIA-backed coup that ended my grandfather’s presidency of Haiti in 1957, the secrecy that shrouded that catastrophe within my family, and how these events rippled into my own life, coming of age in Reagan’s America. It weaves large scale espionage history with intimate stories of individual family members: grandfather, mother, me.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

Most of my life, the wounds in my mother’s early life were kept from me. I didn’t hear about the violence she’d suffered as a girl. Her refusal to address that agony, and my inability to ask, corroded our relationship. Galled by my mother’s silence, I resolved to get to the bottom of it all. It would take me fourteen years to piece together the turmoil that carried forward from my grandfather, to my mother, to me, and then to bring that story to light.

I am certain I would not have endured as a writer were it not for Toni Morrison. Through her work, Morrison gave a ragtag group of people like me the inspiration and permission to write. “There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear,” Morrison once said. “If there is a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, you must be the one to write it.” This story, this book, had been demanding to be written ever since my family—my mother, especially—refused to discuss their past. This book is a restitution of my family’s story.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

Mostly, I am a cultural anthropologist. My happy place is to study other people and whole societies. Writing so intimately about my family and my self was the hardest part of writing this book.

Over the years, as my mother studiously evaded questions that I asked about our family’s past, my curiosity only intensified. My scholarly, detective instincts kicked in. Chafing against my tight-lipped mother, I decided to look for her father elsewhere: the archives. After all, he was a Cold War historical figure. In 2010, I took a bus to the National Archives, just outside of DC. I arrived with modest expectations as to what I might find. Instead, rummaging through the Archives’ cavernous basement over the course of two weeks, I hit a goldmine: more than three hundred pages of memos, spying on my grandfather and tracking his activities.

Dating from 1946 to 1957, these “CLASSIFIED” memos were composed by top-level American diplomats in Port-au-Prince and directed to the U.S. State Department in Foggy Bottom. One of the hardest parts of writing this book was getting some of this material declassified: I had to sue the US State Department in federal district court to have the materials revealed. My suit was rejected multiple times. It was a yo-yo experience of hope and disappointment.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

Every person mentioned in this memoir is real. No one is fabricated. Every family member of mine and every public figure is referred to by her or his real name. However, the names of two acquaintances, with whom I partied at The Cock, a ramshackle, drug-addled gay club in New York City, have been changed.

In this book, I don’t paint just the portrait of my family, but a bold, pugnacious portrait of America—of the human cost of the country’s hostilities abroad, the experience of migrants on these shores, and how the indelible ties of family endure through triumph and loss, from generation to generation. And so, Talk to Me also is an original portrait of a family’s hope and resilience in America from the Cold War to Trumpism.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

James Baldwin, Nobody Knows My Name. Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking. Yiyun Li, Dear, Friend, from My Life I write to You in Your Life. Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Toni Morrison, Beloved. Nicholas Thompson, The Hawk and The Dove.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Do the work. Do the work well. There are no shortcuts, nor substitutes, to a first-rate book. And so, the other important components to literature will matter: public relations, book reviews, conversations.

What do you love about writing?

I relish combing the world for unreported events, neglected topics, misunderstood circumstances; that is, figuring out the stuff of a book. What stories need writing, but haven’t been written? I love knitting my research, corralling my thoughts, and finding the just the right means to express them. Next, I love the daily challenge of putting words together, carefully selected, and in their best order. I love the mastery of thinking and language.

What frustrates you about writing?

When I haven’t figured out what I mean to say, and then my sentences come out sideways.

What about writing surprises you?

I am surprised all the time by what lands on the page—and by how strangers respond to what I have put on the page.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

Yes. I write in the morning regularly, before checking email or glancing on-line.

Most of my life, the wounds in my mother’s early life were kept from me. I didn’t hear about the violence she’d suffered as a girl. Her refusal to address that agony, and my inability to ask, corroded our relationship. Galled by my mother’s silence, I resolved to get to the bottom of it all. It would take me fourteen years to piece together the turmoil that carried forward from my grandfather, to my mother, to me, and then to bring that story to light.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I love traveling. If I don’t travel regularly and to stimulating, new places, then I cannot write.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

Yes. I am working on a book about big money—extreme wealth and risk (financial, investing, romantic, sexual, and life-choice).

Oh shit, I have to read this book. Thanks for the feature.

You are a gift to the world Rich, you, whom Anne Lamont was taking about when she wrote: "we are every age we ever were." As long as you, and passionate souls like you, continue to think, work, excavate, persist, and create, there is still hope for humanity.