Born and raised “in the city,” as the bridge and tunnel people refer to Manhattan, I began watching films shot there when I was just 4, when Mom took me to Radio City Music Hall in 1967 to see Barefoot in the Park. Looking back now, it occurs to me that perhaps that movie that led to my lifelong obsession with New York City on celluloid. That, and the charm of dwelling in that bustling metropolis for 50 years, where every day there was a chance of passing by a film crew shooting on the sidewalk, or encountering them inside buildings I was working in or visiting.

The first time I came across a movie crew it was the summer of 1973, and I was 10. Across from the Battlegrounds basketball courts/playground on Amsterdam between 151st and 152nd Streets, the old 30th Police Precinct building was supposed to be vacant. The cops who worked there had already moved into their new spot a block away. Nevertheless, one morning I saw men moving in huge cameras and milk crates, filled with power cords. Puzzled, I asked one of them, “What are they building in there?” He looked at me and smiled. “We’re filming a picture called Serpico.”

Up until then I’d never thought about films being made — they just appeared on the screen. With my movie-loving mom I’d already been to many Manhattan theaters (from the Alpine to the Ziegfeld), but the actuality of the filmmaking process had never occurred to me.

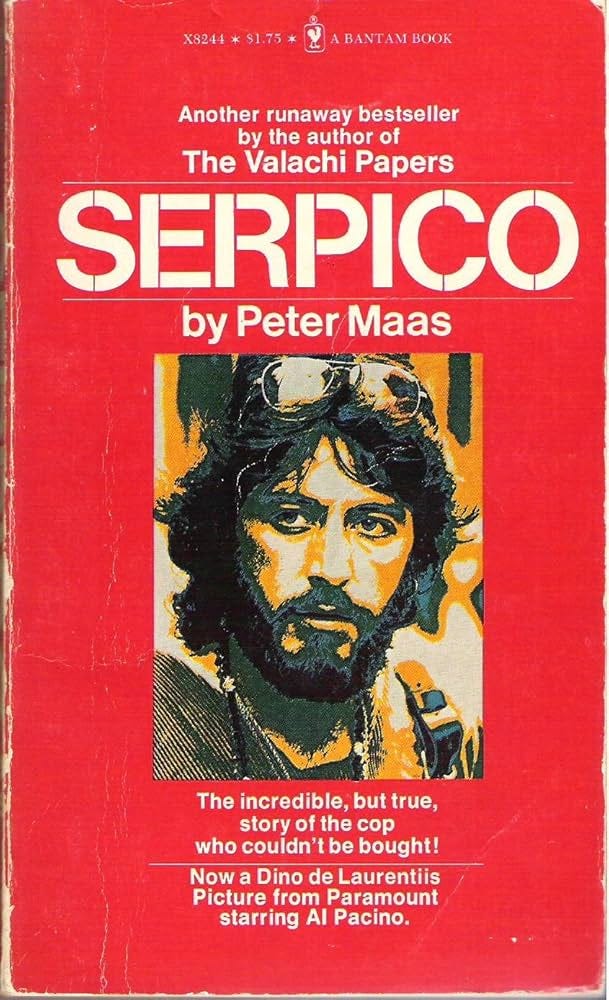

Though I had never heard of “the most honest cop in the city” or the Peter Maas book the film was based on, the name “Serpico” stuck with me. Thankfully, mom brought home The Daily News and The Post every evening, and for the next few months I hoped to see an ad bearing that particular name. Finally, in November, 1973, I saw that Serpico would soon be playing at the Tapia on Broadway and 147th Street, only four blocks from our apartment.

Sitting in that darkened movie house with my brother Perky and our neighbor Darryl, I got excited when I saw that familiar police building come across the screen. I was happily surprised by how much of my neighborhood director Sidney Lumet gave screen time to in that classic. There are a few surveillance scenes shot on a 145th between Broadway and Amsterdam. There’s also as a scene in which Serpico and a crooked cop chase a Superfly-looking perp into the clothing factory that used to be upstairs from the Purnell’s Recreation Center poolroom on Amsterdam between 150th and 151st Street.

The first time I came across a movie crew it was the summer of 1973, and I was 10. Across from the Battlegrounds basketball courts/playground on Amsterdam between 151st and 152nd Streets, the old 30th Police Precinct building was supposed to be vacant. The cops who worked there had already moved into their new spot a block away. Nevertheless, one morning I saw men moving in huge cameras and milk crates, filled with power cords. Puzzled, I asked one of them, “What are they building in there?” He looked at me and smiled. “We’re filming a picture called Serpico.”

The building’s entrance was a shadowy doorway bookended by giant grey pillars at 1828 Amsterdam Avenue. When I was in 4th grade at St. Catherine of Genoa, my friend’s mother worked behind a sewing machine in that factory, and I had gone up there several times. I’ll always remember the scene when the dirty cop finally catches the “bad guy,” he sticks the guy’s face in the toilet and flushes it, because the dude is late with the payoff money. Having grown-up in an era when “Officer Friendly” visited our school for safety lessons and stand-up cop Joe Bolton was presenting television programs on WPIX-channel 11, seeing corrupt cops on screen was shocking.

A month after running into the Serpico crew, I witnessed the filming of a scene from the now-classic Blaxploitation-era film Claudine on the corner of my block. It starred Diahann Carroll as the beautiful welfare mama title character, who was dating cool trash man “Rupert,” played by burly James Earl Jones. One highlight of the night was getting Carroll’s autograph. The other was simply seeing a film being shot. Observing the movie-making process for the first time was fascinating, but also frustrating, as I saw director John Berry film Carroll and Jones walking from his car to the apartment building at 601 West 151st Street multiple times. Before that, I had no idea that it was all so tedious and time-consuming.

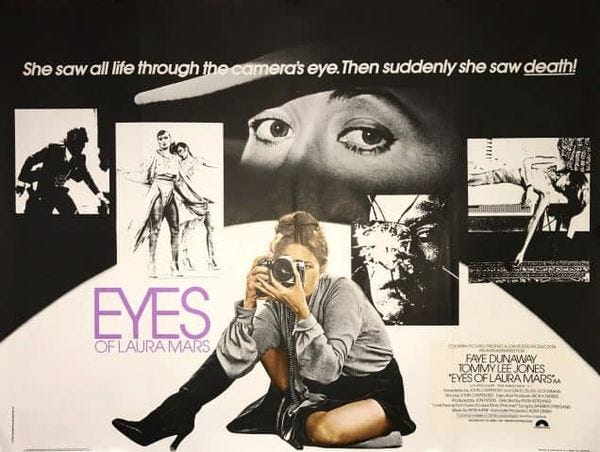

In 1977 I stumbled onto a movie scene that I mistook for real life. That afternoon I was at Columbus Circle, where I had gone to catch a flick at the now demolished Paramount Theatre. After coming upstairs from the subway station, I noticed a wild, highly-styled photo shoot happening half-a-block away. There were burning cars and scantily clad models in garters and furs as the photographer squatted close to the sidewalk snapping shots.

It wasn’t until I realized actress Faye Dunaway was the one snapping the pictures that I grasped the real deal. Today I know that the set-up was an homage to risqué fashion photographer Helmut Newton, but back then I just assumed it was another freak show day on the streets of Manhattan. A year later I saw the trailer for Eyes of Laura Mars featuring that memorable scene.

A month after running into the Serpico crew, I witnessed the filming of a scene from the now-classic Blaxploitation-era film Claudine on the corner of my block. It starred Diahann Carroll as the beautiful welfare mama title character, who was dating cool trash man “Rupert,” played by burly James Earl Jones. One highlight of the night was getting Carroll’s autograph. The other was simply seeing a film being shot.

In 1981 I enrolled at Long Island University, Brooklyn Campus, where I was in the English Department. Two months later I met Jerry Rodriguez, a media arts major who had wanted to be a writer/director. Although I was already a movie buff, Jerry helped heighten my knowledge of cinema through our conversations, lending me books on the subject, and our constant VCR-watching nights.

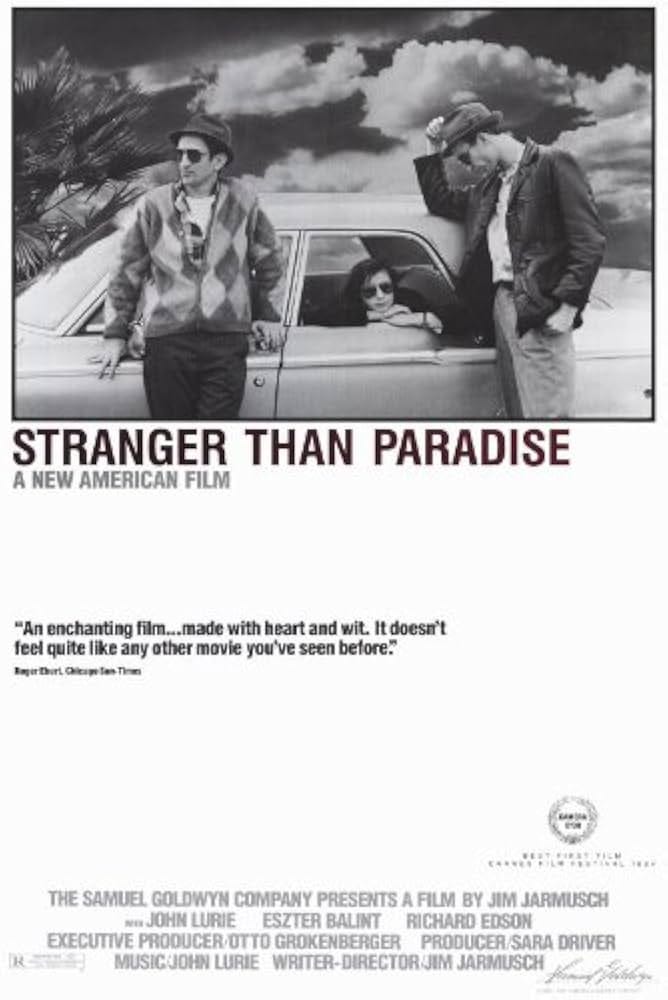

Though I was aware of various filmmakers, both domestic and foreign, I’d never thought about directing anything until 1984, after viewing Jim Jarmusch’s brilliant Stranger than Paradise at the Cinema Studio on 66th and Broadway. I didn’t know much about Jarmusch, but I could tell from watching the movie that he was inspired by punk culture; the film seemed like the visual equivalent of music by The Ramones or Talking Heads. I was instantly transfixed. A year later I rang him up at Tower Records, where I was working, and he bought more cassettes than most.

Stepping into the light after the film, I rode downtown to Jerry Ohlinger’s store, Movie Materials, when they were still on West 4th Street, to buy a Stranger Than Paradise poster. Afterward, I walked over to Washington Square Park, where I made the decision to enroll in an 8mm class at Anthology Film Archives in the East Village, taught by underground director Amos Poe.

Like Jarmusch, I, too, wanted to roam my neighborhood and its hang-outs, camera in hand, capturing the gritty beauty of the town where I was born and raised. Taking inspiration from the sonic collage of the 12-inch single, “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel,” I wanted to film the graffiti kids bombing the subways with spray paint, and domino-playing men on Broadway; I wanted to capture my Black rocker friends playing their instruments on stage at CBGB’s, DJ Hollywood spinning at uptown block parties, and the grimness of the neighborhood boogeyman dope building, 740 Riverside Drive, at the bottom of the hill.

The candid way Alphabet City film folks Jarmusch, Poe, Beth B., Susan Seidelman, Sara Driver, Eric Mitchell and others captured the Lower East Side was how I envisioned filming on the sidewalks of Harlem with the friends, family, and community that I knew so well. Having already dropped out of L.I.U., I had discovered the Thalia where I went often to watch old movies instead of attending class.

Like Jarmusch, I, too, wanted to roam my neighborhood and its hang-outs, camera in hand, capturing the gritty beauty of the town where I was born and raised. Taking inspiration from the sonic collage of the 12-inch single, “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel,” I wanted to film the graffiti kids bombing the subways with spray paint, and domino-playing men on Broadway; I wanted to capture my Black rocker friends playing their instruments on stage at CBGB’s, DJ Hollywood spinning at uptown block parties, and the grimness of the neighborhood boogeyman dope building, 740 Riverside Drive, at the bottom of the hill.

Unfortunately I didn’t have the patience, money or hustle to become the premier filmmaker I imagined myself to be. Yet, without realizing it, I had already begun to channel some of the cinematic aesthetic into the soul/rap/jazz features I wrote for Cover, a downtown alternative arts paper that was my first regular writing gig.

In 1986 I started dating a downtown woman named Initia Durley, an actress who lived in a clothes and book-cluttered studio on East 24th Street, on the second floor of a leaning tenement. Her best friend was actress Suzanne Fletcher, who had appeared in the films of Jarmusch (Permanent Vacation) and Driver (Sleepwalk), as well as the photos of Nan Goldin. Tall, sweet and down by law, Suzanne’s day job was as a typesetter; one of her clients was Cover.

Initia, who occasionally performed with The Living Theatre, didn’t audition or take classes, but sometimes she lucked into opportunities. In the fall of 1988 I escorted her to Silvercup Studios in Astoria when she was hired to be an extra in the Linda Blair B-movie Bad Blood. Though I’d taken acting lessons when I was a kid in hopes that the world might need another Kevin Hooks (the kid from Sounder), that day I hadn’t anticipated being in a film.

In spite of this, when the casting director (another pal of Initia’s) asked if I planned on waiting around all day and I said yes, she replied, “Then you might as well be an extra too. You’ll make $75.00 for the day.” My mother’s cousin Ruth was a crowd scene extra in the 1976 remake of King Kong, so I guess I was following in the family tradition. An hour later I was strolling through an art gallery scene admiring the paintings on the wall, making silent chitchat and standing near the possessed girl from The Exorcist.

When the casting director asked if I planned on waiting around all day and I said yes, she replied, “Then you might as well be an extra too. You’ll make $75.00 for the day.” My mother’s cousin Ruth was a crowd scene extra in the 1976 remake of King Kong, so I guess I was following in the family tradition. An hour later I was strolling through an art gallery scene admiring the paintings on the wall, making silent chitchat and standing near the possessed girl from The Exorcist.

The extras paced back and forth for a few hours, but later I was asked to be in a restaurant scene while Initia wasn’t. Instead of her, they partnered me with another young Black woman, who between takes encouraged me to send my pictures to The Cosby Show. “They’re always looking for guys who look like you,” she said. Though I told her that I “wasn’t really an actor,” she insisted. Initia teased me about this for a week. Whenever I left the house she screamed, “Don’t forget to mail your pictures to Cosby.” We broke-up soon after.

A year later, when Bad Blood had gone straight-to-video, my friend Gregory Grant asked me, “Were you ever in a movie with Linda Blair?” I hadn’t thought about that flick since cashing the check, but I laughed for five minutes straight. “How the hell did you see that?” I asked. Gregory snickered, “Man, I was hangin’ out with some girl and she rented it.”

In 1993, after years of writing treatments and scripts, my friend Jerry finally raised the money to direct his short crime film, El Deseo. A Puerto Rican gangster movie inspired by the work of Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, it starred then unknown actors Benny Nieves and Lauren Velez. Months before securing her role on New York Undercover (and a years before she’d appear on Oz or Dexter), Velez was just another unemployed actress working on a small film in the Big Apple.

Much more fun than watching a movie being made is going to the parties for either the post-production or the premiere party. Over the years I’ve been to a few, including ones for I Like It Like That (starring Lauren Velez, 1994) at Les Poulets, and the Spike Lee film Get On the Bus in 1996 at the Supper Club in midtown. On a mission to meet a friend, I got to see Abel Ferrara, who was there with his arms wrapped around his then-actress/girlfriend Annabella Sciorra.

Jerry invited me to be an extra in the salsa club scene. He was shooting uptown at Broadway 96. He secured the space through his actor friend Paul Calderón who taught a salsa class there. When I walked into the room, I saw Lauren and quickly fell in love. Having no idea that she was one of the stars, I raced over and started talking to her. Suddenly Jerry appeared and told Lauren that she was needed on set. “Can’t you see I’m talking to her?” I said harshly. Jerry stared at me as though I were crazy. “Can’t you see I’m trying to make a movie here?”

Lauren just looked at me, shook her head and laughed. When El Deseo screened the following year, Village Voice critic Ed Morales compared the film’s style to Sidney Lumet’s. A few years later, when I lived in Chelsea, Lauren moved-in across the street. I spoke to her once after spotting her walking towards 8th Avenue with her identical twin sister, but it was obvious she had no idea who I could be. For years I wondered whether I was looking at the right sister.

One Sunday afternoon a year later, I ran into Paul Calderón in SoHo. We knew each other through Jerry, and he was always friendly. Having co-starred in a few of my favorite NYC films including Q&A (directed by Sidney Lumet) and King of New York (directed by Abel Ferrara), I had also studied Salsa dancing with him. As we walked and talked, we ran into Spike Lee. “Hey Paul,” Spike greeted him. After they stopped and chatted, Lee shouted, “Call me, Paul, I have a part for you in my next movie.” When Spike was gone, Paul began laughing. I looked at him, puzzled. “Do you know how many times he’s said that to me, and I haven’t been in a Spike Lee Joint yet.” I, too, started laughing. Nevertheless, a year later I was shocked when Paul popped-up in Lee’s adaption of Richard Price’s criminal minded masterwork Clockers playing a character named Jesus.

Much more fun than watching a movie being made is going to the parties for either the post-production or the premiere party. Over the years I’ve been to a few, including ones for I Like It Like That (starring Lauren Velez, 1994) at Les Poulets, and the Spike Lee film Get On the Bus in 1996 at the Supper Club in midtown. On a mission to meet a friend, I got to see Abel Ferrara, who was there with his arms wrapped around his then-actress/girlfriend Annabella Sciorra.

In pure fan-boy style, I walked over and began gushing about how much I loved King of New York and Bad Lieutenant. Looking like a cool dope fiend (which he was), he shook my hand and mumbled, “Thank you, man,” in a voice that reminded me of Tom Waits’. “Are you one of Spike’s actors?” Ferrara asked. I assured him I was just an admirer of his gritty NYC films. There was a small pause, then Ferrara asked, “You want to come with us over to the bar?” After we got our cocktails, we found a few seats and basically talked about his films.

One of my last chance encounters with a movie crew happened in the winter of 1998. Strolling through Times Square at 6 pm, it was already dark. While walking on 43rd Street from Broadway to 8th Avenue, pedestrians were asked by a pesky production assistant to stop walking; that request didn’t go well. “Who the hell films in Times Square during rush hour?” someone screamed. The PA looked nervous, as though the mob might attack…“They’re making the new Martin Scorsese film, Bringing Out the Dead,” she replied nervously.

When I lived in Chelsea in 1997, Jerry and I were walking down 7th Avenue when we noticed a new bookstore called Fox & Sons had moved into the 17th Street storefront that had once housed Barney’s. We were equally excited, but when we went inside there were no shelves, books or magazines. Instead, burly men were hanging lights and boom mics.

“Can I help you guys?” a hardhat-wearing worker asked.

“We thought this was a new bookshop,” I replied.

The man chuckled. “No, this is the set for a movie called You’ve Got Mail.” I sucked my teeth. “A movie set,” I snapped, feeling betrayed. I was so pissed that, when the film starring Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan was released, I refused to see it. To this day, I still haven’t.

One of my last chance encounters with a movie crew happened in the winter of 1998. Strolling through Times Square at 6 pm, it was already dark. While walking on 43rd Street from Broadway to 8th Avenue, pedestrians were asked by a pesky production assistant to stop walking; that request didn’t go well. “Who the hell films in Times Square during rush hour?” someone screamed. The PA looked nervous, as though the mob might attack.

“They’re making the new Martin Scorsese film, Bringing Out the Dead,” she replied nervously. By chance, I’d recently read the crazed Joe Connelly novel about the wild adventures of EMT workers struggling to do their jobs in Hell’s Kitchen and Times Square. At the mere mention of the name “Scorsese” the crowd chilled. Certainly, New Yorkers feel an affection for real NYC movie makers that mirrors their love for the town itself.

“Anything for Marty,” the man next to me yelled. We all laughed. Afterwards, the crowd was quiet until the scene was shot.

40 years ago, I was walking up 5th Avenue right above Washington Square. I encountered yet another movie crew and yet another PA telling me to not cross the street. I decided to be defiant and kept walking. Suddenly, over the cries of the poor PA, thousands of pieces of torn paper came raining down from the highest floors of One Fifth.

A year later, I went to see the new Nicolas Roeg movie, INSIGNIFICANCE. Suddenly, in the middle of the movie, Theresa Russell as Marilyn Monroe opened a window (I think it was her character - I haven’t revisited it since it came out) and homemade confetti fell over lower 5th Avenue. The cutting seemed a little too frantic (as opposed to regular Roeg fragmented cutting) and I realized with embarrassment that I had almost ruined their shot.

This feels like life in New York City—hope to visit next year.