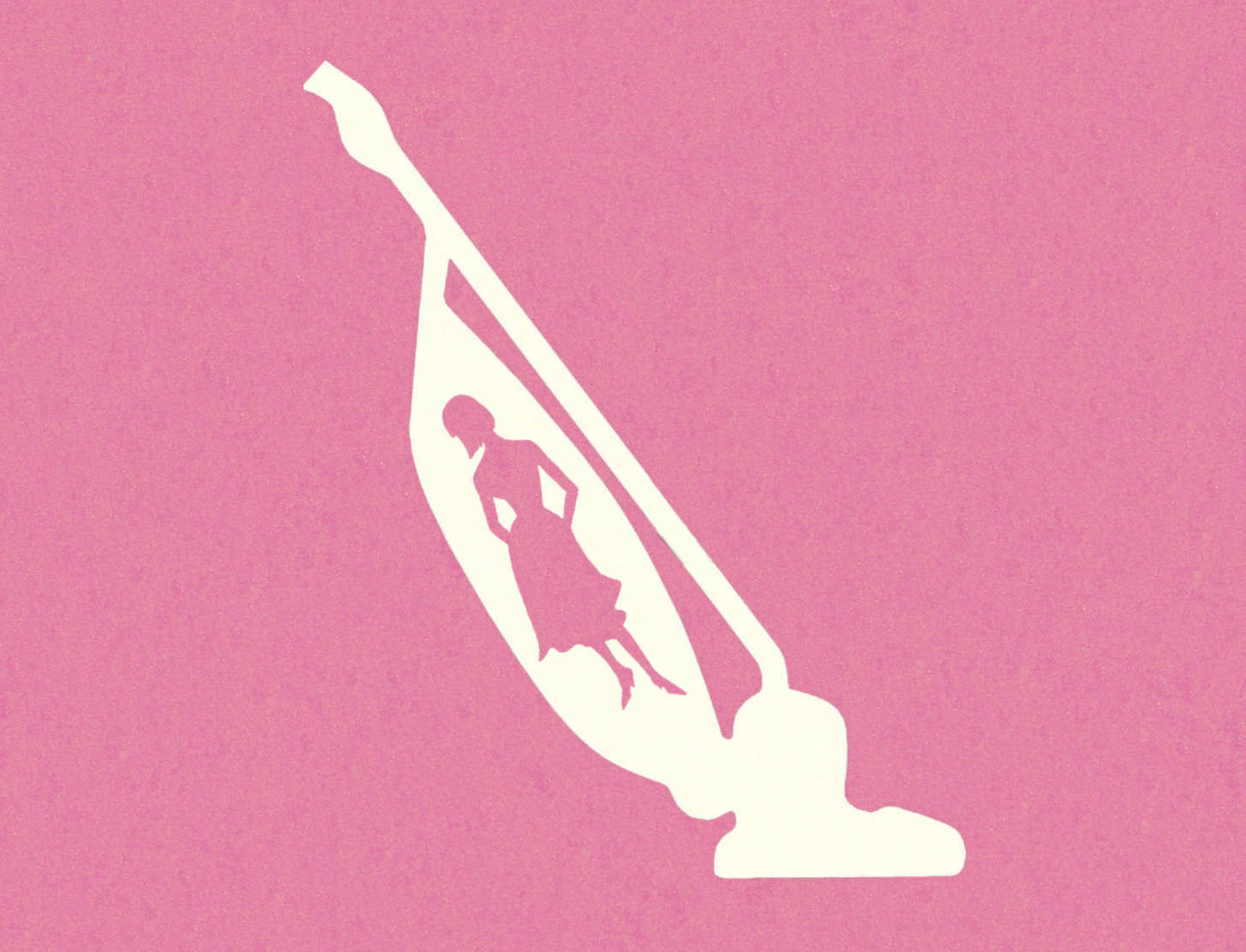

I hate vacuuming: the smell of heated dust, the low roar as dead skin cells, mites, food bits escape and mist around me. I hate the machine’s heavy body and the retractable cord that snaps out of the wall and whips my ankles. When I change the bag, I turn the canister on its side, on its bottom, on its other side until the release valve pops open and spews grey furred dirt onto my bedroom rug.

After my husband Jerry’s fourth amputation, the removal of infected bone from his foot, he returned from the hospital attached to a vacuum. His Wound Vac pumps blood, fluid, and infection from the deep hole on the side of his foot through clear plastic tubing to a see-through collection canister.

It’s more than I can bear. While we eat, read the newspaper, watch tv, the machine sits on his lap or hangs on the arm of wheelchair, gurgling, beeping, refusing to let me forget, for even a second, the mess of illness and old age.

I can’t. I can’t do this anymore, I say to myself, my mantra, my cantra, the same thing I said when he first needed a wheelchair, when he first became incontinent.

When we married, I was thirty-six and Jerry, a vital, seemingly healthy fifty-two. Before our first anniversary, he needed an angioplasty. Thirty-five years later, we’ve been together through more heart stents, femoral artery stents, a rare salmonella infection that lodged in his groin, spine surgeries, hand surgeries, sinus surgery, and the repeated foot wounds and amputations resulting from his diabetes. His hands are clawed by nerve damage making it difficult for him to hold utensils and vascular dementia limits his ability to understand his condition or make decisions about his care.

I can’t. I can’t do this anymore, I say to myself, my mantra, my cantra, the same thing I said when he first needed a wheelchair, when he first became incontinent.

For the first two months he’s attached to the Vac, a wound care nurse comes to the house three times a week to change his dressings and switch out the collection canister.

“Can we get a new one today?” I ask the nurse, turning away from the see-through container, its sides coated with pus and blood, what the instruction manual refers to as “exudate.”

“Medicare pays for one a week. Yours isn’t full yet.” She snaps off her nitrile gloves.

I sigh.

“Okay. I’ll look in my car. Maybe I can find you one.”

I follow her out to the street. Our next-door neighbor, Mr. Kim, waves hello. We’ve been renting this house for the two years since Jerry’s illness forced us to sell the big house we’d lived in for thirty-five. Goodbye Moroccan tile, green paneled library, Wolf range, panoramic views. Covid began just a few months after we moved and the few conversations I’ve had with Mr. Kim have been muted through masks. I wonder what he thinks of the frequent ambulances. I wonder if he knows that I’m sixteen and a half years younger than my husband, that I miss salsa dancing, that I want to go to Barcelona, or if he just sees me as part of the old couple who live next door.

***

“You’re wearing leather pants. And jazz oxfords.” Jerry said to me the night we met. “And is that a cape?” He gestured at my shoulder, where my asymmetric red tunic snapped with big hardware.

He didn’t know how seductive I’d found his attention to my clothing, his awareness of fashion. That night, I found out that he was acting in a play at my favorite local theatre, that he loved crosswords, and that he’d written a book of logic puzzles. A few weeks later, he gave me a yellow index card with all the two-letter scrabble words, a gift I use to this day. We slept together on our fourth date. His passion for books and reading, the way he flexed his chest so that his snap-front denim shirt popped open, told me that I’d met my match.

When I moved into his house a year later, I found his battered old Hoover in the garage, its dark brown plastic body splattered with white paint.

“It’s from the store,” he told me.

His father owned a chain of shoe stores. By the time we met, Jerry was no longer practicing law, but handled the stores’ finances to support his acting. My family had been in the garment trades too. Early on, the discovery that we’d both grown up in family businesses, that our ancestors came from the same parts of Poland and Russia, that we’d both been raised by elegant, stylish mothers, made me feel that we’d been family before we’d met.

But after living with Jerry for a few months, I saw that the only housework he did was emptying garbage and washing dishes. Part of my attraction to him was his spontaneity. He’d presented himself to me on our first Christmas morning together naked but for a string of lights. I couldn’t find the words to broach the mundane subject of chores.

So I dusted, cleaned the bathrooms, swept the kitchen floor, and pulled the heavy vacuum up and down the stairs. Clearly, a straight-forward conversation about the division of labor was in order but I was afraid to find out that Jerry and I disagreed.

He happily supported me while I wrote and taught part-time, but did that obligate me to clean? My writing kept me closer to home, but was my work less significant than his vetting leases for the stores? I considered myself a feminist, but if the upheaval of the sixties changed who cleaned the toilets, I wasn’t sure how to enact the revolution in my own home.

“This house is a lot to keep up,” I began one night when he got home from work, his tie loosened like a sit-com husband’s.

“Don’t feel that you have to clean for my sake,” he said.

It wasn’t the answer I wanted.

“My mother,” I switched direction. “We always had a housecleaner, a person who came once a week.”

“Hire someone,” he said immediately.

In photos from the first ten years of our marriage, I’m always pressed up against or draped across Jerry’s body. I loved the tight set of his ears, his long thighs, his soft curly hair.

My neck un-tensed. The talking points I’d been rehearsing in my head quieted. We hired a housekeeper and avoided an important discussion, setting expectations for the upkeep of our home. Not a great precedent, but I felt relieved.

In photos from the first ten years of our marriage, I’m always pressed up against or draped across Jerry’s body. I loved the tight set of his ears, his long thighs, his soft curly hair. His size twelve feet were especially handsome, long second toes and soft, princely skin with not a corn or callous or the bunions that had already started to distort the shape of my own feet. I liked sniffing the back of his neck and giving him little bites. In bed, I rubbed my face across his chest, drinking him in.

“Closer, closer,” he whispered when we made love.

My big breasts resisted flattening, but we mashed together, no space between us, for that moment, melded to one.

“You’re beautiful,” he whispered. “Inside and out.” His eyes glistened the green brown of wet trees.

“You too,” I breathed.

But our marriage wasn’t all easy attraction. After I had four miscarriages and he refused to adopt, I cooled. He’d been married before, had lost an eleven year old son in a car accident. I suffered PTSD from being raped as a teenager. We both brought, and I hated the word, unless it was filled with beautiful clothing, “baggage.” But I still loved us together, close, but independent.

In his mid-seventies, his health worsened. I’d understood intellectually that because of our age difference he would probably face serious illness before I did but I’d never colored in the pictures. I never thought that we’d stop replacing his damaged teeth. I never anticipated the difficulty of transferring him from his wheelchair to our bathtub shower bench or deciding that his shower could wait another day. I never imagined I’d have dozens of close-up photos of necrotic foot wounds on my phone, his once lovely feet now oozing infection, pics I sent to his doctor with the subject line: “Should I bring him to the emergency room?”

***

“Do I want an electric car?” I ask him softly.

He’s prone on his recliner, two hours into a fidgety nap and I’m lonely for the person I used to discuss everything with, for the brain that used to beat me at Scrabble, for the partner I used to have.

I thought that we’d always be attractive, that I’d always desire him, that he’d always smell good. I’d never pictured being married to an old man with greasy hair and a food-stained shirt.

“Would you wear that shirt with those pants?” I barked at one of our aides the day she’d dressed him in navy blue sweat pants with red stripes down the sides and a pilled green and brown plaid polyester shirt. The worst shirt in his closet. “Have some respect!”

I’d had a bad morning: the stove broken for a second week with no response from the landlord, a rejection from a magazine I’d convinced myself would love my work, and a bad reaction to the drug I’d been prescribed for my recent diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

I apologized to the aide a few minutes later. How could I be so petty, so unappreciative, so superficial? She changes his diapers, checks his skin for bedsores, his feet for wounds. She squirts eye drops, nose drops, administers enemas, pills, insulin. She washes his clothes.

Earlier in our marriage, I did his laundry. I felt a romantic, almost erotic charge when I handled his jeans, his chili pepper bikini underpants. I loved that he was a man who wore a lavender flowered shirt. Now, his wardrobe is sad: sweatpants with snaps down the legs for easy diaper access, diabetes socks. And his clothes are dirtier: food, blood, urine, pus. I finally understand the “Sanitary” setting on the washer dial.

The agency lists “light housekeeping” among the aides’ duties, but I have asked them not to wash my clothes. My laundry waits in a separate hamper—a solitary pleasure just for me. Other than cooking, laundry is the only housework I enjoy.

Sometimes I stare through the window on the washing machine mesmerized by the heartbeat chug of my swishing clothes. The transformation from dirty to clean floods me with pleasure. I love flat-drying a hand-washed sweater on a fluffy towel, tugging the sleeves a squinch longer. I love the warmth of fabric straight from the dryer on my arthritic fingers, the heated aromatherapy of my favorite lavender detergent. Novelty socks, the bonsai knee-highs that remind me of my father, the angel socks a friend sent after Jerry’s last surgery, amuse and comfort me. Pairing socks orders the world.

***

It is Monday, garbage night. In the garage I struggle to close the lid of our black pail. I pull on gloves and try to press the bags of Jerry’s soiled diapers lower in the can. The stench of elimination rises around me. I punch the wall button and the garage door grinds open. The wind bays, a sound like a coyote being swung by its tail.

I go outside in my bathrobe and sweatpants, unprotected from the rain. I wheel the cans up the slope of the driveway, water seeping through the soles of my slippers. An “atmospheric river” the meteorologists are calling it, words that marry romantic getaway with catastrophe.

My marriage—most marriage—is eventually all of us facing decline and loss.

Mr. Kim wheels his bins, secured with bungee cords, to the curb too. I envy his control. Whenever I’ve tried cords, they go missing after one use. I know that I’ll wake up one morning and find our cans knocked over. That raccoons or rats or whatever monsters come out at night, will have pulled the bags apart. That everyone will see our shit.

“How are you?” Mr. Kim wears a dark raincoat with a stand-up hood. “How’s your husband?” His mask muffles his voice.

Through his open garage door, I hear a baby’s cry. The Kims have a beautiful, fat-faced boy with a shock of black hair and glittery eyes.

“We’re fine,” I say. “How’s your little son?”

“Getting big.”

I stare at his black pail as he speaks, feel as if I can see through the plastic to a litter of wipes, flattened food pouches, diapers smeared with ointment and poop. Jerry’s mess is not that different from a baby’s, only more voluminous, less adorable.

“I hope you are not disturbed by his crying.” Mr. Kim presses his hands together.

What disturbs me is my marriage. For the last ten years I’ve viewed our difficulties as an afterword, a sad addenda, circumstances so outside my expectations, they seemed to be happening to someone else. Our early heat replaced by caretaking, extravagant gifts by his forgetting our anniversary, home remodels reduced to raised toilet seats and grab bars. My sadness and grief, my rage, have so clouded my vision, it has taken a while for me to see what is obvious. This is marriage too. My marriage—most marriage—is eventually all of us facing decline and loss.

Mr. Kim goes inside. The wind blows back the lid of our bin. Raindrops pelt my face and the unfastened bags. The diapers, soiled gauze, clogged tubing, alcohol wipes, betadine swabs, and used Enluxtra, the priciest dressing, the Lamborghini of bandages, seem to rise in the can, screaming out their existence, demanding their own sloppy place.

I go inside and sit on the corner of Jerry’s hospital bed.

“You’re wet.” He swipes at my face with his fist.

His nail snags my hair but the gesture is tender. I lean in, closer, closer. For one second, the old heat rises. I kiss him goodnight.

Thank-you, Michele. You're not alone either.

Thank -you for the good advice!