Déjà Vu

Human/Animal author Amie Souza Reilly on repetition, revisiting past experiences in new contexts, and Derrida's concept of "iterabillity."

I bumped a woman at the grocery store. My cart hit the open glass door she’d propped open to reach for some lettuce. She looked at me through the glass, surprised, probably rightly annoyed. Even though I had never seen her before, her face was familiar. I opened my mouth to apologize and floated a little bit out of my body, as if my thoughts were happening ahead of time. I remember thinking whatever I said next had to be right, as if this grocery store moment had been prearranged, my déjà vu an uncanny test and I couldn’t make a mistake. The woman’s baby smiled at me, and I couldn’t remember whether I was supposed to smile back.

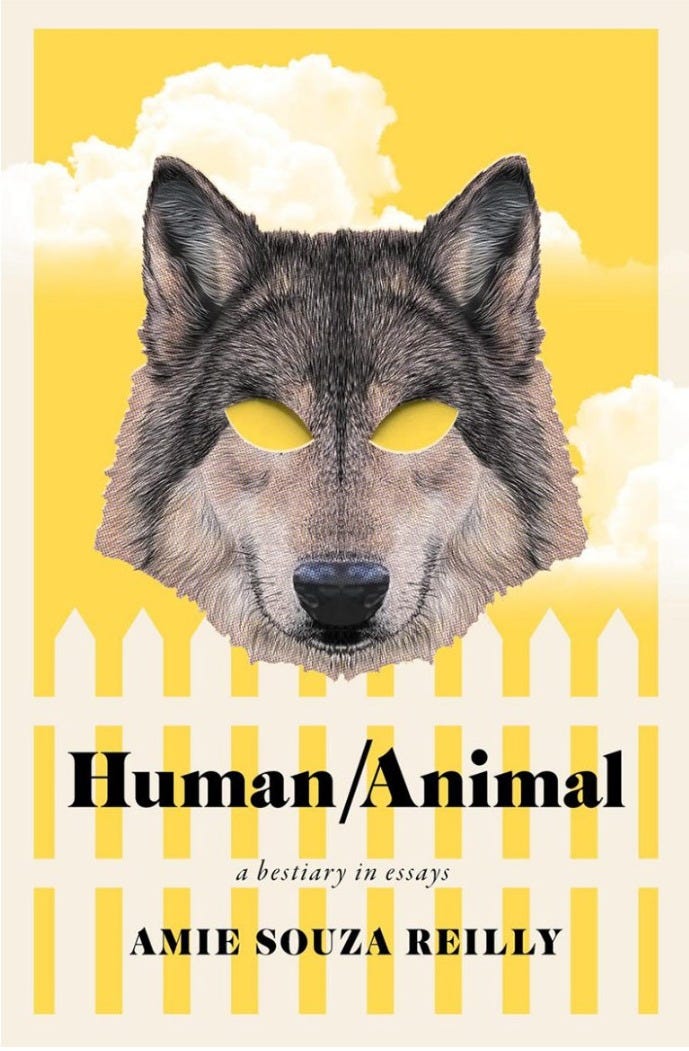

I recently published a book that is unequal parts criticism, bestiary, and personal narrative. I spent years reading and rereading stacks of theoretical texts about gender, race, disability, literature, history, film, culture, and animal studies trying to contextualize the personal narrative, which is about the two brothers who used to live next door to us. Those men tried for years to push me and my family out of our house so they could buy it, even though they already owned two of their own houses. It was the narrative about the brothers that was the hardest part to write and is still the more difficult part for me to read.

In fact, five days before the book’s launch party, I still hadn’t read it, hadn’t read it at all in months, not since the last round of copy edits. It’s not that I wasn’t thrilled—I had taken pictures with it, signed a few early releases, answered some interview questions, even bought an outfit and a new pair of shoes. However, despite my excitement, despite knowing I needed to reread it to choose excerpts to share aloud and prep for questions, I just...couldn’t.

I recently published a book that is unequal parts criticism, bestiary, and personal narrative. I spent years reading and rereading stacks of theoretical texts about gender, race, disability, literature, history, film, culture, and animal studies trying to contextualize the personal narrative, which is about the two brothers who used to live next door to us. Those men tried for years to push me and my family out of our house so they could buy it, even though they already owned two of their own houses. It was the narrative about the brothers that was the hardest part to write and is still the more difficult part for me to read.

There’s an essay by Hanif Abdurraqib called “On Seatbelts and Sunsets” where he writes of, in, and around loss and love through acts of god, acts of man, memories, and repeated images. At one point, he writes of Interstate 270, which loops around Columbus, Ohio. At first, the loop is a comfort—“you might get a couple of shakes from United Dairy Farmers and circle the city with a person who looked perfect first in the sunlight and then the streetlight”—but later in the essay, Abdurraqib’s car is stolen. The car thief ends up on that very same highway, unaware or temporarily forgetting there is no way out of the loop. He flips the car, the seatbelt strangling him to death. The loop, for the car thief, was like a déjà vu mistake.

Depending on what you read, repetition can be a way of working through trauma, or a comfort, or a sign of madness. It is a way for us to remember, and this is why, for example, there are so many epithets in The Odyssey. Regardless of why or what we’re using repetition for, there always needs to be a memory. However, there’s a shift, a break, that happens when the memory moves from one context and becomes associated with another. A repetition becomes a hybrid thing made up of both the memory and something else, something new, other, changed. Derrida called this iterability.

When we were little, I used to sit knee-to-knee with my sister to play a game about time. See now? one of us would say, and then snap her fingers, It’s gone. Over and over again, trying to suspend ourselves between past and present, realizing I think, somehow, that we were moving forward even while sitting still. This is how I understand Derrida’s link between repetition and otherness. Something happens, but even while happening, there’s a haunting of what will happen next: It’s never the same, or is already not the same. Repeatable, but shifted. That feeling of slightly-tilted, a little uneasy, flinging forward while sitting still, also feels to me like déjà vu.

The loop of I-270 in Columbus that Abdurraqib describes is a shape made of repetition. Also, it was once a memory of comfort that becomes a memory of tragedy. When I teach this essay, because I know how it ends, his first description of the highway is already shadowed by my memory of the accident, which has not yet happened for my students. Perhaps that is a little bit how it feels for Abdurraqib, too. Two memories at the same time, on loop, in a loop. See now? Snap. It’s gone.

I couldn’t bring myself to reread the book before the launch party because I knew what was inside would feel like that, too: two memories at the same time, a wrong déjà vu, everything I’d written back then exactly the same, but shifted, not just for me, but for America, too.

One of the many difficulties I had when writing about my neighbors was recalling the sounds of their voices. Not just what they said, but how. The brother most guilty of stalking, yelling, trapping, and violating our privacy spoke in fragmented, repetitive threats. He used repetition to emphasize his power, his verbal tic a reminder that he could and would take up more space. In our driveway, his threats to me circled around and came back. You are a terrible mother. I will report you to authorities. No one rude like you should have children. I can report you. I know people. I know powerful people. I can report you and they’ll believe me. I’m a powerful person.

When we were little, I used to sit knee-to-knee with my sister to play a game about time. See now? one of us would say, and then snap her fingers, It’s gone. Over and over again, trying to suspend ourselves between past and present, realizing I think, somehow, that we were moving forward even while sitting still. This is how I understand Derrida’s link between repetition and otherness. Something happens, but even while happening, there’s a haunting of what will happen next: It’s never the same, or is already not the same. Repeatable, but shifted.

If this description feels familiar, it is because my neighbor spoke just like the president.

Much of the book I wrote contextualizes the brothers’ behavior within larger understandings of white heteropatriarchy, their desire to own more of our neighborhood a microcosm of settler colonizer violence, what some might describe as a déjà vu of cultural memory. The first draft of this book started in 2020. I turned in the finished manuscript in 2024, just before the re-election. I had hoped by the time Human/Animal came out, the microcosm of my family and the macrocosm of the country would both be somehow healing, moving forward. But I was wrong. And now I had to ask others to read it, to hear what I heard, what we are all hearing, again. The same, but different.

I didn’t want to return to the book because I felt I couldn’t hear or speak simultaneous violence. How can we endure the same story twice, let alone endless times? The loop had closed. But the truth is in there, these men, that man, are behind lots of fences.

I opened the book, then I opened my mouth, and I knew what to say.

Now I have to get the book. It will scare me silly. It will bring back . . .

This book blew my mind! And knowing how crafted it is, truly a work of amalgamation, I loved reading behind the scenes here from Amie!