Eleven True Things

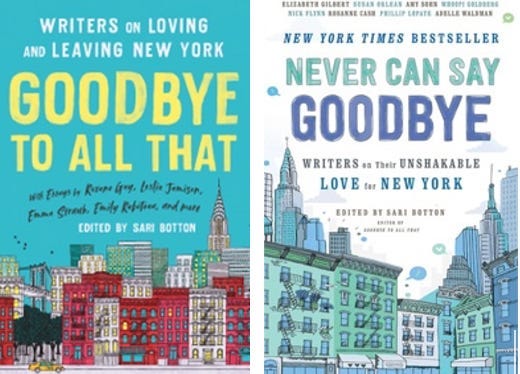

Ada Limón looks back on her time in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. An excerpt of Goodbye to All That: Writers on Loving & Leaving NY.

1. The Planter in Times Square

I hate everything about the moment the City starts to leave me. That’s what it feels like. Not as if I am ready to leave, but that the City is pulling away from me. Like a relationship you know is over and still you go on kissing each other on the cheek and silently grinning through your teeth because how can it possibly be over, a love as big as this? I am standing near Times Square by my office and my stepmother has just died and I am putting my hands in an enormous concrete planter and before I know it I am crying from the feel of dirt, the real leaves of something living. I don’t want my life anymore, not the way it is. I need more space. More time to think and make things. Someone hits me from behind accidentally while coming out of the subway. They don’t apologize. Some part of me is embarrassed, because I am stopped in the middle of the sidewalk in midtown which feels like the middle of everything; a real New Yorker would know better. A real New Yorker doesn’t look up or down, they look straight ahead. They are propelled by momentum. They don’t stop.

2. Things That Cost a Dollar

When I first move to New York I beg my friend T to meet me at the airport. T has already been in New York for two weeks and when I call her she says,“No one picks up anyone at the airport in New York.” She is already a New Yorker. I know this. I fly a discount airline that no longer exists and somehow T meets me outside. I have three-thousand dollars saved from working as a receptionist for King County Water and Land Resources Division. It’s August. I am twenty-three. I start graduate school at New York University in three days. Though I know very little about poetry, I am going to study it. T has short hair and a pager attached to her jeans when she picks me up. No one but drug dealers or medical personnel have pagers back in Seattle. Pagers are fancy. In the cab she keeps talking about the street food you can buy for a dollar. She says a slice of pizza is a dollar, pizza rolls are a dollar for like a whole bag, soft pretzels are a dollar, hot dogs are a dollar. Then, she turns to me and asks to borrow a hundred dollars. The blur of traffic and gray exhaust-filled air, the tall buildings, the rush of pedestrians, the cabdriver who doesn’t seem to care where we want to go, I want to remember all of it. Mostly, I remember T showing up. Even though she said real New Yorkers don’t show up at the airport.

3. Nothing Costs a Dollar

Discovering New York is like discovering a different color. Something you’ve never seen before that’s on par with both beauty and agony, and looks both terrible and fantastic on everyone. I walk everywhere. One day I walk from Battery Park to Central Park all while carrying the fat Norton Anthology of Poetry in my backpack. It’s impossible to look cool wearing a backpack. I don’t have a cellphone or a pager. I have an actual fold-out map that is small enough to fit in my pocket. I walk because I want to see the city. I also walk because I am terrified of taking the subway. The subway is a color I recognize. Something like a putrid yellow of disgust and urine and florescent lights and warmth and danger all at once. I discover jaywalking in earnest and how it’s best done together as a heard. When I get lost, I look downtown and see the twin towers. The towers always mean that way is south. A bottle of water is a million dollars. Drinks are a million dollars. I am losing money so fast and suddenly it seems ridiculous that anyone would go to New York to be a poet, and not a banker instead.

4. The Shirt

I have one nice shirt that was given to me by my friend Diana. It’s Pierre Cardin and it’s black, long-sleeved, ribbed. It somehow never fades or stretches out. T and I have to swap this shirt on street corners if either of us have to go to some place nice. We only ever call it, “The shirt.” I still have it. We hand wash it, not because we are being delicate with it but because it is needed more than twice a week. If we have to go some place nice together we are screwed, because who gets to wear “the shirt”?

5. The Literary Wing

T and I move to Greenpoint, Brooklyn in 2000. Everything is done in cash. We hand over 2400 dollars and it’s more money than we’ve ever seen. From then on we pay rent to a twelve-year-old who brings it back to her parents. We give her cash and hope she gets home okay. T says to her while she counts out the hundred-dollar bills, “Well here’s a hundred dollars for every year you’ve been alive.” We get the go-head to paint the walls. We stay up late, listen to a classic radio station, take mushrooms a friend has given us, and paint the whole apartment terra cotta. For years you can still see areas where we got distracted and the paint thinned out. I write poems. T writes plays. T’s father sends mail to us that is addressed to “Apartment 2L, The Literary Wing.” We do our laundry at a laundromat where you can smoke inside and get grape soda out of the vending machine. We don't get many channels on our small television and one night the lady at the laundromat stays open late so we can finish watching the Academy Awards while we smoke and drink grape soda. We love our laundromat. We love our apartment. We love our deli. We are living the dream.

I need more space. More time to think and make things. Someone hits me from behind accidentally while coming out of the subway. They don’t apologize. Some part of me is embarrassed, because I am stopped in the middle of the sidewalk in midtown which feels like the middle of everything; a real New Yorker would know better. A real New Yorker doesn’t look up or down, they look straight ahead. They are propelled by momentum. They don’t stop.

6. Stone Soup

The first temp job that T gets is at GQ Magazine. The first temp job that I get is at GQ Magazine. By the time I get my job at Condé Nast, I’m in my second year of graduate school and T has already gone on to a better job. I shop at secondhand stores to get most of my work clothes and supplement with new cheap things from Rainbow Shop. Everything from the secondhand store smells like body odor and smoke and everything from Rainbow Shop smells like plastic and burnt hair. We cash our small paychecks at a busy check cashing spot in midtown and then walk around with hundreds of dollars of cash in our pockets like our twelve-year-old rent collector. The money we don’t spend on rent, we spend at bars. That’s okay because everyone we know does the same thing. We make a family out of our friends. We are chaotic and unstoppable. We are making stone soup. We are the stones. Our friends provide everything else. We forget where we are from except when it is late and we’ve been drinking and someone gets a little homesick, or wonders whether someplace else is still easier, a little softer. We don’t stay too long in that place of our origins. We pay our tabs and go back into the crackling dirty city that has become our home.

7. Laundry and Trees

I spend most of time in graduate school writing poems about California and using words like eucalyptus and bay laurel and manzanita. When I sit to write a poem, each time, I return in my mind to a place across the street from where I grew up in Glen Ellen, California where the Calabazas creek runs underneath Arnold Drive. I think if I can get to that place of stillness, of curiosity and wonder, I can write a poem. When I look out my window in Brooklyn, I see the square backyards that we can’t access and all the laundry looping from house to house like broken kites. I grow tomatoes on the fire escape. A friend of mine in my same poetry workshop introduces me to someone at a bar and says “This is Ada, she writes poems about horses and rodeos.” Which is strange because I have never written about a horse or a rodeo.

8. Harrison Ford

The towers come down. Nothing is the same. I begin having panic attacks. No one has ever loved New York more. We cry and lean on each other. There’s a fundraiser we volunteer for hosted by our friends who are actors and also own a shop that refurbishes old muscle cars for movies. The fundraiser is for our local firehouse that’s lost men. The fundraiser is also a hipster paradise with live music and a kissing booth and I work the bar for a long time. If I am busy working I do not have a panic attack. At one point someone is walking toward me with the light behind him so I cannot see his face but I know him. It is Harrison Ford. He gives an apologetic smile and I try to pretend that I see him everyday even though he is my favorite actor of my childhood. I do not call him Han. I do not call him Indy. I ask how many beers and tell him it’s donation only. He throws a wad of cash into the bucket and grabs six beers for his friends and two off-duty firefighters. Somehow, now and forever, I associate the terrible grief of September 11th, absurdly, with Harrison Ford.

9. The Impossible Garden

We move into a real house on Metropolitan Avenue between Bedford and Berry. H moves in with us so we can split the whole house which comes with a small backyard. And for the first time in nearly five years, I make a garden. When it’s nice, it’s the only place I want to be. I am working for Martha Stewart and I become a homemaker. I make an herb garden and grow lettuce and tomatoes and an accidental boomer crop of okra that T wanted to plant. That’s the same year I discover I don’t like okra. T and I try to write a song that starts, “When okra was our cash crop.” That’s the year we all start to think about ourselves in the past tense. When the furniture is settled and the house is perfect, H lies on the couch we found on the street and says, “I’m already nostalgic for this time right here.” This is the house I am most happy in. It is the only place I’ve had in New York where I can be outside and alone at the same time.

10. The Last Apartment

I live in the last apartment I’ll have in New York for four years. It’s a small one bedroom with a good bathtub on Manhattan Avenue between Jackson and Withers in Williamsburg. It’s the place where I begin to think about leaving New York for the first time. My stepmother becomes very sick with cancer. I lose my friend who is my same age to cancer. I begin to think about what it might be to live in nature, to stop grieving so much, to be away from concrete, to stop working so hard in jobs I don’t love. I try to save a little money for the first time since I’ve moved to the City. I make a plan for an interim place to live in California. I don’t believe that it will really happen, but someday maybe I will leave this place. But leaving New York is impossible. It’s as if you are the gum and it is the hair; you are stuck and the more you pull away the more it hurts and tears you apart. T and I begin to prepare ourselves for months before I leave. We make a plan. We cry. Six months before I leave, I fall in love. It is most inconvenient. It is feels like a cruel trick New York is playing on me.

11. The First Day

I drive up Moon Mountain Road to where I am renting a small apartment in my hometown of Sonoma, California. It is October and unseasonably warm. As I am driving, I see so many birds along the road. I see bay laurel and California oaks and manzanitas lining the path. I do not have any place to be and nothing is required of me. There are two things happening. I am grieving. I am untangling myself. I cry the whole way up the mountain, but I feel like I should be happy. I suddenly miss even Times Square. I think I’ve made a mistake. I don’t know what to do with myself. I am nothing without the City, without T. Everything is a new color again and this time it is something that hurts to look at it because it is as if I have made the color up. A color I haven’t told anyone about, a private color. I stop in the middle of the country road and take a picture of the sunset and send it to the man I love and then I send it to T. She says it’s so beautiful it makes her want to poke her eyes out. I keep driving. I am propelled by momentum. I do not stop.

I’m having haunted memories of driving my packed car, and my yowling cat, on the BQE under the Brooklyn Promenade, and learning that Harry Chapin had died, and knowing that my life as a New Yorker was over as well. And yet it was also the start of so much for me. You just can’t see it from the bleak promontory of an ending, with everything behind you and nothing but cliffs visible ahead. I popped Steely Dan’s greatest hits into the tape deck and kept going. The cat sang along.

A portrait of nostalgia and the fear and love that's always part of that feeling.