Goodbye, Hello, Goodbye...Hello

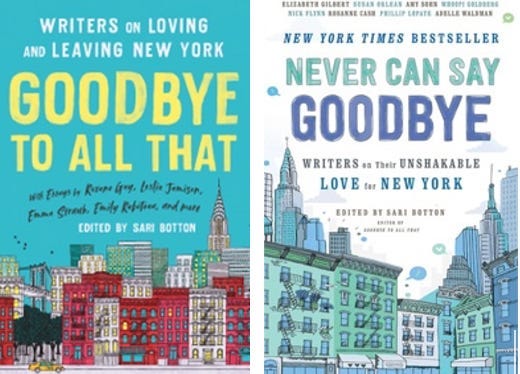

Carolita Johnson on her many exits from—and returns to—NYC, most recently to care for her aging mother in Queens. An excerpt of Goodbye to All That: Writers on Loving & Leaving NY.

I’ve left New York three times over a span of twenty-eight years. The first time I was twenty-three and headed to Paris. I returned home eleven years later, worn down by my life there as an illegal alien. The second time I left, at age thirty-five and feeling exploited as an independent contractor in New York, it was to embrace France’s employee benefits and national health care as a “legal alien.” The next and last time I left the place that we who don’t live in New York City call “the city” was five years ago, to flee the rising rent. I landed in Kingston, New York, where the rents recently began rising at an even faster clip than downstate once the big city folk caught the scent of cheap real estate and fresh air at a shorter commute than it takes to get to Coney Island from Midtown Manhattan by subway. I was fifty when I arrived in Kingston. For five years I lived there as an artist, writer, café employee, and finally, as an artist-in-residence, teaching a course at SUNY New Paltz.

On my second return, eighteen years ago, when I came back to start writing and drawing, I began the way most people do: my sentimental education, the romantic adventures and relationships that formed my emotional intelligence (or lack thereof). Five years ago, I’d been annoyed, writing about my more recent life, that my story would appear to end with me moving in with my partner of fourteen years and, even more of a cliché, getting married. But our life didn’t end “happily ever after.” We were legally married for exactly three days, and my life continued, not quite so happily ever, after death threw my life a plot twist. Four years ago, I became a widow in a small city a hundred miles away from “all that.”

I’d been moving northward ever since my last return, starting with Brooklyn, then across the river to the Lower East Side, to Harlem, and then, with a partner, to Inwood. When he turned sixty-nine, I decided it would be wiser to skip getting priced out of the Bronx in five years, so we made for the Hudson Valley, to Kingston, where I thought we could live unfettered by financial worries into his old age.

In Kingston, I never had to network. Kingston networked me. A nondriver, I walked everywhere and saw people all the time, especially once I got a job at the local café. I’ve always thought it’s utter snobbery to live in a city and not work in it, so I applied for and got a few shifts there within a month, even before I needed the money, which I certainly did, later. When my partner was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer, everyone knew it and kept an eye on us and helped me care for him. When I found myself alone again, I wasn’t really alone. Kingston was there for me.

My first apartment as a widow in Kingston was like nothing I’d ever seen before. It was $975 a month. It was built in 1920, rather dilapidated, probably a fire hazard, and was a full block deep, with twenty-foot ceilings. It was divided railroad style into four rooms separated by three sets of walnut pocket doors. A windowed shaft (to provide light and air in the middle, darkest room) in the apartment above me had been removed in my identical apartment, leaving a semiconcealed trapdoor as a scar in my ceiling through which I could hear my upstairs neighbor sneeze occasionally. There were indoor “windows” and transoms designed to maximize the distribution of daylight, two disused fireplaces, and an ingenious thing called a central vacuum cleaner, which was once operated by plugging a hose into holes in the floors that connected it to a giant vacuum in the basement.

The wonder of it led me to take breaks from weeping and panic attacks by scouring microfilmed newspapers for information about its builder and all the prior residents and businesses that had once occupied it. On a roll, I began to list and research my previous addresses and discovered that all my old apartments in New York City had been turned into luxury rentals, many of which had even been subdivided into at least one more bedroom than I had once had, sometimes two more. The rents had tripled, hair-raisingly. If I hadn’t considered it yet, the idea of returning “home” to the city now seemed like a cruel joke. How had it come to this?

The same would soon happen to my next Kingston apartment. Nine months after I found it, the building was sold, and the new owners—fresh transplants from Brooklyn—ended my month-to-month arrangement and more than doubled the rent.

***

I’m a true New Yorker. My parents met at Roseland, a dance hall that was, until recently, in Manhattan, at 239 West 52nd Street. Four years later I was conceived in an apartment on West 73rd Street, known as the Upper West Side and then born and raised in various parts of Queens.

I bring this up because I know that all recently arrived and incoming New Yorkers like to tell their friends who visit them in, say, Queens, that Queens is New York City, but I’ll tell you this much: no one in Manhattan ever said “I’m going to the city” if they were on their way to any of New York’s other boroughs. No. Going to the city means you’re going to Manhattan, aka “the city.”

I don’t care what anyone ever taught you about the five boroughs of New York City. The only part of the city that is the city is Manhattan. Yeah, I’m from Queens: I’m proud to be a tough kid from Queens who has to watch her language around my more genteel New Yorker friends. I’m not from the city. I know that the city is as exquisitely cruel as it is sublime, and I only like living there as long as I can get away from it whenever I want.

That is not an issue for me right now because the rent is too high for me to live there. But guess what? Kingston was recently named “the Brooklyn of the Hudson Valley,” and now the rent is going up there, too. I say “there” instead of “here,” because six months into the Coronavirus pandemic that began in March of 2020, I left Kingston, and returned to Queens, where I am now living with my 85-year-old mother, caring for her a year-and-a-half after my father died.

What with the “citiots” coming to buy a house or two—seriously, I’ve heard them talking about the “couple of houses” (or even three) they’re buying—my former upstairs neighbor (also a woman artist) and I aren’t the only tenants I know who have been booted from a building by a new owner. These new owners tend to be people who say things like, “It’s gotten so expensive in Brooklyn that we moved up here, and, oh my God, we hate to be those people, but…”

I don’t care what anyone ever taught you about the five boroughs of New York City. The only part of the city that is the city is Manhattan. Yeah, I’m from Queens: I’m proud to be a tough kid from Queens who has to watch her language around my more genteel New Yorker friends. I’m not from the city. I know that the city is as exquisitely cruel as it is sublime, and I only like living there as long as I can get away from it whenever I want.

But. They actually are “those people.” The current tenant of my grand old five-room apartment in the heart of Kingston’s “uptown” neighborhood moved there after getting booted from his old duplex apartment across the street by more of “those people.” Me, I moved a couple blocks away into a very rundown apartment with a rent closer to pregentrification levels but was denied a lease: I imagine that’s because my landlady wouldn’t mind selling the building, and can you blame her? She promised not to “screw me over.” My goodness, I tried to tell her, it wasn’t her I was worried about. It was the potential new owners I feared.

I tried not to think about them. I was there almost three years before leaving at the end of August, 2020. The attic—my studio/guest room—sometimes had a faint aroma of hamster, probably because the previous renter had a mouse infestation. I’ve lived in worse. One of its advantages was its proximity to the bus station: I could get on a bus and be in “the city” in a few hours.

***

I would go to the city about once a month for a long weekend to see my friends but also to make sure I don’t lose my edge. New York has a short memory and is changing all the time: I needed to see my editors, my agent, my peers, not to mention my siblings. Luckily, at any one moment I had at least three different friends I could crash with, and I tried to divide my time with each of them equitably so I didn’t overstay my welcome anywhere. My custom was to clean their apartments on my way out, figuring I was a virtual, unpaying roommate and it was the least I could do. I have to admit it also made their apartments and, by extension, the city feel like home to me.

By contrast, Kingston is small, and because of this I saw my upstate friends and acquaintances every day, which meant I could work from home but never really be alone. All I had to do was go down the block to the café for a cortado, and everyone was there, no need to make a date and no need to linger—though I often did. The café was practically an extension of my own apartment where I could sit and work, often surrounded by people I loved doing the same.

Most of my friends there were women, indubitable feminists and fiercely individual in contrast to many of my women friends in the city. I think this is related to the low rent. Up there, where rent on a one-bedroom apartment was, until recently, typically only $700 a month and where it remains half as low as city rents, you could toss your misbehaving man out on his ass and still make the rent. Affordable rents put women in a position of strength. I’ve seen too many women in the city who, out of financial desperation, stay with or delude themselves about men they wouldn’t hesitate to leave or read the riot act to if only they had what is known as “fuck you” money. (NB: here the words “men” and “jobs” can be considered interchangeable. More than one kind of toxic situation could be improved by affordable rents.)

***

When I found myself doing spit-takes over how high the rent had gone on my vermin-infested dumps of yore, I had a brilliant idea: I looked up “women’s boarding houses,” recalling the ones I’d seen in old black-and-white movies like Stage Door, where a woman of limited means coming to the big city alone could rent a room with a bed, a desk, and a bookshelf to live in safety with her fellow entry-level earners and aspiring artists.

Too late: except for one outlier, they’ve all become hotels or luxury versions of their former selves, marketed to highly paid professionals or interns whose parents ostensibly pay their board. Women in retail or in the service industry today, who are often older and single, could never afford these rooms. It’s hard to understand why the women’s boarding house is obsolete now that it would be more useful than ever.

I see women my age and older lose their jobs while they’re still young enough to work but too old to be rehired at entry level. Highly paid professionals, they’re typically laid off and replaced by their assistants just before they’ve finished paying off their thirty-year mortgages. Single women starting out, or who have worked for decades barely making their livelihood and whose rent will soon outpace their income, women returning to the workforce after taking care of their aging, dying parents or spouses—they compose a growing demographic that will need a place to live in safety and a sense of community.

It’s a fond pastime of us aging, single women to imagine, often over drinks, our fantasy Golden Girls household, inspired by that TV series about four older women living their golden years together. There is one last boarding house in the city that I want to someday try to get into for a year before it joins the others in extinction. This is not a romantic notion: I want to see what it’s like and how it’s run because I think this kind of living arrangement needs to make a comeback, albeit updated for modern womanhood to include all our sisters. In the meantime, though, I am cohabitating in Queens with only one proverbial Golden Girl, my mom. One thing I’m grateful for is that my mother has completely forgotten how much she used to despise me. We watch old movies together in the appallingly cluttered and dusty living room, and they trigger memories of her youth in Ecuador and how, sixty years ago, when she forgot her suitcase in the taxi to the airport, and arrived in New York City with nothing, unannounced, and (unlike me), couldn’t leave.

In Kingston I could only just afford to live alone while living off my writing and drawing. My two shifts at the cafe were a bonus that disappeared with the coronavirus outbreak. Though I missed my young colleagues and the social contact, such exposure could make me a constant danger to my vulnerable friends and family. I could spend the next winter “Zooming” with them from anywhere. Maybe being a true New Yorker is what makes me so willing to sacrifice so much to find meaning in life.

I wonder what will become of Kingston. A friend, who has been right about everything regarding this pandemic and its repercussions, predicts that more people from the city than ever will move up here and work remotely, away from the potentially contaminated crowds or buy safe houses here to flee to upon the next pandemic, driving rents up further. He thinks rents will get lower in the city as a consequence, but I think that won’t happen until there are laws in place prohibiting landlords from warehousing, keeping apartments empty for years, writing their losses off while they wait for tenants who will pay high rent.

Meanwhile, I have a feeling I’ll be back in Manhattan again some day, but how I’ll do it remains to be seen. The truth is, I know that wherever I go, there are people with more money right behind me who will price me out within five years or less. Knowing this, I usually take a two-year lease and sign twice before looking to move again. I always look for working-class neighborhoods like the one I grew up in, which, by the time I move out, I have helped gentrify by my very presence there, making me part of the problem. I slink in, and slink out, knowing that where we artists go, the upwardly mobile follow. We’re a virus, ourselves. You’ll never hear me say “Move to my neighborhood, the rent is so reasonable” again. But I know silence isn’t the solution.

If I move back to Manhattan, it will mean I found a way to afford it as easily as the people I used to pave the way for (unlikely!) or, hopefully, that I was part of a change. Perhaps we’ll meet at “The Carolita” someday.

For now, though, I am enjoying Queens. My neighborhood has gone from unpleasantly white (I refer to the bigots who bullied me here in the 80s) to mostly Asian and Latinx now, the opposite of what my neighborhood in Kingston was becoming when I left. I’ve found my local cafe here, where I write in my journal for a break from cleaning and DIY home repair, and find I’m happy to pass on Manhattan for now. And yeah, I could say I’m back in “the city,” like the gentrifiers so often say in Queens. But I’m too much of a snob.

Thanks for this. Makes me feel less alone. I fled New York (the city) for Long Island and Long Island for rural California. And got "priced out" everywhere. The fine spirit of Carolita is a pick-me-up! In England 50 years ago, a group of women working at a small press bought a house together, shared expenses, child-care, etc. and seemed to be making a go of it. My dream.

Ohhhh I love the idea of The Carolita! Since moving back to SF from New Zealand to care for my aging parents at the end of their lives, I've been doing my best to figure out something that makes it more possible for writers and artists to exist and practice in San Francisco. Clement Collective is my best attempt for now. But that's more a space to gather and create, rather than something residential, which really is the crux. Gears turning... Thanks always for your excellent writing, as well as this specific inspiration! <3