Happy Messes

Thanksgiving: A holiday about family and food and connection…except when it isn’t.

There are many ways to cook a turkey, all of which require heat. When I was 12, in 1974 my mother forgot to turn on the oven. Thanksgiving afternoon I idled through the rooms of our small bungalow, reading Jaws, playing with my toddler cousin while the adults, my uncle and aunt, and my mother, drank wine and tequila and laughed in the dining room. I’d already set the table for five with our bamboo placemats and the red gingham napkins my mom loved, tucked beneath our mismatched silverware. A pinecone and construction paper turkey which I’d made back in elementary school sat next to the ashtray. Their lit cigarettes, maybe a joint too, offered up tendrils of smoke.

I don’t remember much happening in the kitchen. I peeled potatoes and dropped them in a pot of water on the back of our old enamel stove. But I do remember the absence of roasting turkey smells. When my mom decided it was time to baste, she discovered she’d forgotten to turn on the oven. Hilarity for the grown-ups, my mom laughing and rushing to the bathroom to pee. My tiny cousin fell asleep on the couch. Hungry, I scooped up bourbon yams, my uncle’s signature dish, straight from the casserole.

We did eat turkey, around midnight. The streetlight shone through the dining room windows, stubby candles flickered, and the ashtray had been moved. The grownups had coffee with their meal. We passed a small pitcher of my aunt’s ridiculously smooth gravy; her secret was cornstarch, lemon, and constant stirring. No one cared about the crater I’d made in the yam casserole or the late hour, and my little cousin, sitting on her mother’s lap, stabbed a fork into the canned cranberry sauce.

***

“Thanksgiving is a crap holiday. We should fast this year.” My mother repeatedly made this announcement in the fall of 1977 when I was 15. She’d be unloading groceries in the kitchen—plain yogurt, honey, coffee—and suggest we drive up the coast Santa Cruz to Año Nuevo Beach. The last time she took me “up the coast” she ate psylocibin and tripped while I watched the waves, too big to play in, read James Michener, and worried. This was during her Carlos Castañeda period, a time during which she was seeking insights.

Lucky for me my aunt and uncle put the kibosh on her fasting and beach plan. Next she suggested using the Weber grill to cook the turkey and everyone, remembering the cold oven and late meal, said absolutely not.

“I’ll make the turkey,” I said.

The three adults turned to me, my mom allowing a closed smile, my uncle squinting and dropping a hand on my shoulder. My aunt asked, “Are you sure?”

Of course I was sure. No one is more certain than a 15-year-old who’s never done it before. I’d perfected chicken and dumplings from the back of the Bisquick box. How much harder could a turkey be? And so, the mantle was passed.

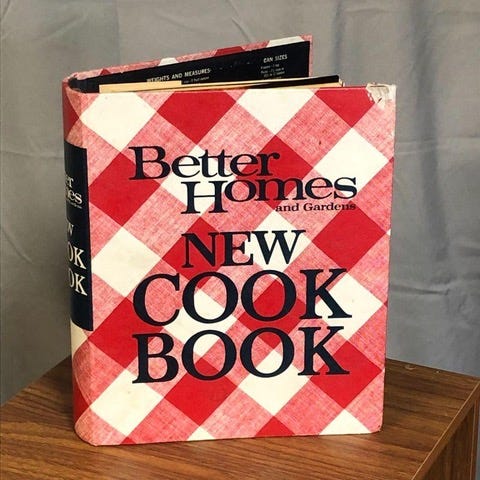

I studied the red and white checked Better Homes cookbook my grandmother had given me. I kept lifting and dropping the needle on Carol King’s Tapestry album while I chopped herbs with the Ginsu knives my mom and her boyfriend had ordered from an infomercial at two in the morning.

Morning glories climbed the fence just outside our kitchen window, shining their proud blue faces at competent me. I knew to thaw the turkey in the kitchen sink. We all did back then. I made stuffing with Pepperidge Farm mix, adding apples and onions, then jammed the cavity full. Once I’d smeared butter all over the skin, I slid the bird in a slow oven.

My best friend and I had been making cut-offs from our jeans, trying them on, slipping them off. Cutting them shorter. More leg, half-moons of butt flesh revealed, the white fabric of the pockets hanging down.

When I checked the turkey, the skin was bronzing too quickly. I’d read about tenting, placing a folded foil hat over the breast, to prevent burning.

“What’s this?” My mom, who’d been grading student papers most of the day, stood behind me with her sudden opinions. I described the tent and its function. Maybe it was her bad mood, or my know-it-all tone, but my mother was now in my business.

“No way.” She crumpled the foil and threw it aside.

“Mom! I’m doing this.” I smoothed the wrinkles.

“You think you know everything?” She leaned close. “How do you think I made it this far?” She swept her arm grandly around the kitchen.

I insisted, she refused. The tent became the most important issue of the day.

“It’s my turkey!” The tent ripped and I yanked a second, dramatic, overly long piece from the roll, relishing the small thunder clap of rattling foil.

“Over my dead body!” This from the woman who’d wanted to fast.

“Your choice.” I blocked the oven door with my body. It was my first turkey. It was Thanksgiving. A holiday about family and love, the most important turkey I could imagine. My mom stomped away, slamming her bedroom door. My friend and I hopped on our ten speeds and pedaled to the cliffs overlooking Seabright beach. Distant fog lumbered toward puny waves breaking near the shore. Soon we’d be wrapped in the gauze of it. We tipped our bikes onto the ice plant, sat in the dirt in our new cutoffs, and passed a joint. The shift in mood that came with the weed, the slight floaty sensation in my brain, made me laugh.

“Don’t you tent that turkey!” my friend said.

It was hilarious. We were hilarious, and young, with long, bare legs.

We stayed at the beach, high and hungry on Thanksgiving, just as my mother had initially suggested.

***

At 19 and married to my first husband, I was a student of all things Martha Stewart, trying for a new life. Thanksgiving was decidedly not a crap holiday. For my new husband, I’d decided to double stuff this turkey, my fourth. I’d make two stuffings, one without bread of any kind, just sausage and onions and herbs, which I would carefully spread between the skin and the flesh of the bird, as Martha had directed. The second stuffing included chestnuts and pears, hazelnuts and cornbread, and would fill the cavity.

Not only was I going to be reliable, I’d be stellar. I’d gone to Macy’s and bought a paisley red skirt and blouse, suitable for Nancy Reagan, along with kitten-heeled pumps. I pulled my hair into a chignon and tied a white apron around my waist. From a yard sale I bought someone else’s family heirloom, a silver platter I made my own. I planned on making an entrance.

And I did. Only the sausage stuffing had relocated like old pillow stuffing, misshaping the turkey, giving it lumps and bumps in all the wrong places. My aunt whisked her gravy at the stove, my mother set out the napkins, filled wine glasses. “That’s some turkey,” she said, grinning. Somewhere there is a picture of me, holding the platter in the doorway between my mother’s kitchen and dining room.

I am so young. I am so disappointed in myself.

***

In my 30s the Thanksgiving meal became a prelude to the main event. Our family was deeply committed to Mafia, a conceptual parlor game. We squished together on the plaid sofas in our living room, sat cross legged on the floor, balancing plates of apple pie on our knees.

“Night falls on the village,” the game began. “Day breaks and ____________ (a family member) is dead!”

We killed each other late into the night, trying to win, to discover who was Mafia and who was a mere villager. Cousins and boyfriends, my forever husband, our children, strays, my aunt and uncle, my mother, we all leaned in. We had leaves in the table, linen napkins, the turkey bought fresh from a farm. Bourbon yams, my aunt’s gravy, winter squash and laughter. We walked on the beach to catch the sunset, good pinot noir in our coffee cups, arranging ourselves on a log, snagging a stranger to snap a picture. These were the Thanksgivings I had dreamed of in my Martha Stewart days, only with a smidge of danger.

“Night falls on the village.”

One year, perhaps in my zeal to discover who was mafia, or to hide my own mafia connections, I killed my daughter, only 6. What kind of mother does that? Kills her girl? Her face went red, she stomped from the room. Everyone turned to me; even I turned to me, shocked.

***

After my bi-lateral mastectomy we were reeling, waiting to learn about oncotypes and tumor grades, about sentinel nodes and the future. My cousin hosted Thanksgiving while my immediate family fell apart. Our children, now in college, fought hard over things like who rode shotgun, who got the better room in the Airbnb. My mother, sullen, silent, and afraid, booked herself a massage.

My husband flitted from person to person, trying to assuage. I couldn’t roast a turkey, peel a potato, or lift my arms over my head. When my jittery husband ran a red light on the way to my cousin’s home for the meal, our 19-year-old son exploded, made a speech insisting that everyone but him was falling apart, and now he would have to be the patriarch of the family. Which was hilarious and somehow broke us up in the best way.

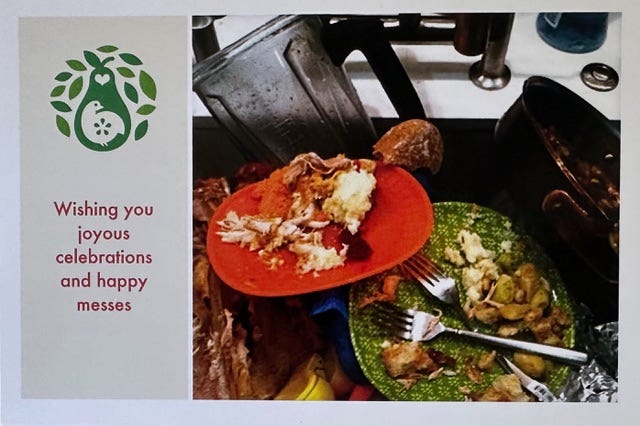

We did not get a family photo for the holiday card. Instead, before I slipped away to nap, I snapped a picture of heaped dirty dishes in the sink. It was the best we could do.

Wishing you joyous celebrations and happy messes, the card said. We sent it to 100 friends.

***

And isn’t that the way of it? Happy Messes should be perfect for Thanksgiving, family around the table, lumpy turkeys, dinner at midnight. Perhaps avoid fasting or killing our babies, but perfection is not what I seek.

Last year we declared Thanksgiving a crap holiday, a lie about imperialism and appropriation, extermination and forced migration. We switched up the whole tradition to a South Asian feast and a Tom Hanks movie binge. Butter turkey! Forest Gump!

I don’t know what this year will bring, other than a grilled turkey, stuffing on the side, roasted carrots with cumin, mashed yams, my aunt’s gravy, a pear cranberry pie, all the family together. My mother will repeat herself and remember little that’s said. My late uncle will still be gone. My aunt will nod and smile, hearing little but so happy to look down the table at all of our faces. There will be new babies. My cousin’s husband will lift the bird from the grill. I’ll toss a salad with a garlicky vinaigrette. We’ll walk on the beach, ask a stranger to take a picture of our happy-in-this-moment, messy family.

Love this and the people in it!

This is the best tribute to messy families and messy holidays and our great aspirations- thank you so much!