How I Survive as a Writer Through Public Speaking

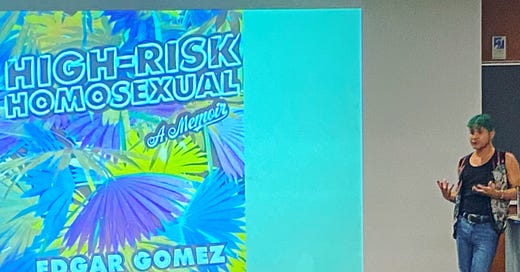

"High-Risk Homosexual" author Edgar Gomez on the validity of caring about money as an emerging writer, and his experience creating a new income stream that’s about—and supports—his work.

When I was younger, I thought all writers were rich. To be fair, I didn’t know any in person, but the writer characters I saw on TV shows like Sex & the City and movies like 13 Going on 30 spent their days having martini lunches and nights attending book launches wearing designer outfits, so how could they not be? Though I grew up admiring these characters, I would be lying if I told you I dreamt of being a writer as a kid. What I dreamt about was stability. My mom, back then a barista at Starbucks, supported our family on $22,000 a year. My dreams were far more ordinary than book parties in New York. As a teenager, I fantasized about working at a cubicle, because it meant I’d probably have a home and a car and dental insurance. It wasn’t until I took my first creative writing class in college and received positive feedback on a story that I thought: Oh, maybe you’re good at this? Maybe this is how you can make a living?

From that moment on, I became hyper-focused on becoming a writer. Yes, I had a passion for literature. Yes, I believed in the power of words to promote social change and make people feel less alone. And yes, those things mattered immensely to me, but I also believed publishing to be my way out of poverty, and that’s important, too. It’s why I rolled my eyes (on the inside) at the author who once told me, “You can always tell when a writer only cares about money.” Sure, only caring about money often leads to bad art, but after years of doing everything from sex work to cleaning up literal shit customers left behind in dressing rooms, I wanted to scream, “Sorry my stories would probably smell poor to you!” Instead, I went home and wrote.

Most of what I’ve learned about publishing I picked up from observing other writers. When I wasn’t sure who to send my personal essays to, I chased my memoirist friends’ bylines and submitted there. When I had no idea where to even begin looking for grants, I opened the novels on my bookshelves and made a list of all the places the writers thanked for “their generosity.”

In 2022, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, my debut memoir, High-Risk Homosexual, was published. Prior to that, I’d paid my rent in New York doing a handful of service-industry jobs, all of which abruptly let me go during the mandatory lockdown. So I was pretty excited to have money coming in. And I assumed, because of the myth of the rich writer I’d bought into, there’d be a lot of it.

The reality was that my book only got me $15,000. Before you come for me, I know that’s not nothing. In fact, for a debut, it’s pretty nice—though it’s not anything close to the obscene amounts of money equally unknown straight, white, male writers are paid. However, I didn’t get to keep all of that money. To break it down for those who are unfamiliar, that $15,000 was the “advance” for my book, which is basically the total amount a publisher pays for the book, and will likely be the only pay the writer receives unless it becomes a bestseller. Take 15% out of that figure—$2,250—for agent fees, bringing my advance down to $12,750. Then there are taxes to be paid. On top of that, advances aren’t given in one lump sum. After taxes, after your agent takes their well-deserved cut, you are typically paid in installments of three or four: when you sign the contract, when you deliver the manuscript, when the soft/hard cover book is out. In my case, $15,000 translated into roughly $3,500 a year for three years. L-O-L.

All that to say that between helping my mother—who lost her job at Starbucks during the pandemic—and paying my rent, by the time my book came out, I was basically broke again. I could write on and on about what a disappointment that was, how devastated I felt upon discovering how seemingly impossible it is to survive as a writer, but I think it would be enough for you to imagine me lying in bed, staring up at the ceiling, having desperate one-sided conversations with the patient, gender-nonconforming higher powers I pray to.

They went like this:

Please GOD I am SO TIRED please let me have A BREAK please I CAN’T ANYMORE please I DON’T KNOW HOW LONG I CAN DO THIS please please please please.

And after I was done wallowing, I did what I always did. I got my ass up, because rent was due.

It might be helpful for you to know that most of what I’ve learned about publishing I picked up from observing other writers. When I wasn’t sure who to send my personal essays to, I chased my memoirist friends’ bylines and submitted there. When I had no idea where to even begin looking for grants, I opened the novels on my bookshelves and made a list of all the places the writers thanked for “their generosity.” And that day when I finally got out of bed, I remembered hearing from a writer that she made most of her income from speaking engagements.

At the time, I didn’t understand what she meant by “speaking engagements.” Speaking about what? And to whom? And for how much?

I was curious, so I did a little digging and got answers:

About what? Her talks were about subjects she studied in graduate school and wrote frequently online about.

To whom? Usually to universities, some corporations, literary festivals, conventions.

And how much? I didn’t know, but I figured somewhere around $2,000, plus flight and accommodations. This was fully just an educated guess, though.

I remembered hearing from a writer that she made most of her income from speaking engagements…At the time, I didn’t understand what she meant by “speaking engagements.” Speaking about what? And to whom? And for how much?…I was curious, so I did a little digging and got answers:

I didn’t have much money, but what I did have was a book out. For some reason, the gender-nonconforming Gods looked down kindly upon me, and High-Risk Homosexual received a rave review in The NY Times, and was featured in Nylon and Entertainment Weekly. A video of me twirling around with my book wearing a knock-off of JLO’s Versace dress went semi-viral. These things, I thought, could be considered a “platform,” and I could parlay that into speaking gigs.

(I’d like to mention here that the person I got this idea from did not have a book out. This is not one of those nice pieces of advice that are, in fact, impossible to follow. Her platform was articles published, usually online, and her degree. But a platform could also be a larger-than-average Twitter following. It could be unique expertise. It could be anything. Who cares? Come up with something and as long as you’re good at talking, have at it! I read a tweet recently from writer Vanessa Chan that said that when she worked for a corporation, her job would hire mediocre dudes to speak to employees about “owning the room” and they’d charge $95,000. As another great tweet I read somewhere said: Lord, give me the strength of a mediocre white dude.)

Personally, I would feel wild standing up in front of a group of people and blabbering about nonsense, nor do I think I could get away with that, so I opened my computer and made a list of subjects I could reasonably talk about for about 45 minutes, leaving 15 at the end for Q&A. High-Risk Homosexual is about queerness and machismo and growing up in the south, so those were three things right there. And I’d written a memoir, so I figured I could talk about the process of memoir writing too. Then I took that list and drafted paragraph-long outlines of what those talks would cover and put them on my website. Notably, I didn’t actually write the speeches yet. I didn’t want to waste my time doing all that until I got a booking.

Because of the buzz High-Risk Homosexual was getting, I already had a few people hitting me up on my website so they could invite me to do readings at their schools. I took those opportunities and asked if they’d want me to give a whole talk, for the same cost (back then, they were setting the price, which usually was between $250-$500), and sent them my speech blurbs. All of them said yes. Then I went off and drafted the actual speeches.

In practice, that looked like—

Someone emailing me: Hey will you come do a reading at my school?

Me: I’d love to! Did you know I also do talks? They have a reading component!

Yes, I recognize that to get here you already have to be getting invited to read, which is no small feat. If you’re a writer and not sure how to get the ball rolling, consider pitching a panel to a literary conference like AWP, pitching seminars to online schools like Hugo House and Lighthouse Writers, perhaps creating Twitter threads or other online content on your subject of expertise, letting your followers know you’re available for podcast appearances or appearances on their panels—whatever it takes to build up your platform and position yourself as someone with something to say who can be booked to give a talk. That includes having a website with a way to contact you and information about what you talk about. Preferably, with pictures of you doing the thing. People like seeing pictures.

The next part was all trial-and-error. I visited schools (usually locally or virtually; no one was flying me out yet), gave the talks, paid attention to what was working with audiences and what wasn’t, and slowly made them better. Gradually, I began to ask for more than I would charge for a regular reading, and I also began to post about the talks on social media, so other interested people would know they could hire me. AKA: Advertising.

The more time I spend in the publishing industry, the more I’m learning that getting a book deal probably isn’t going to solve all your money problems; however, if you’re crafty enough, you can finesse your book into other opportunities that might: freelancing, teaching workshops, grants, and now speaking engagements.

As the months passed, lockdown restrictions were lifted and traveling to give talks became an option again. In addition to my fee to speak, I started to negotiate flight and hotels into my contracts (I’m beginning to charge $2,000 now, plus flight and accommodation, which is on the lower end). Soon I realized that I was making more from my talks than from anything I’d ever written. Not $95,000, but each talk netted me nearly enough to live on for a month, affording me time to do the thing I love—writing—without only “caring about the money.”

Like with my first book deal, while on the surface $2,000 sounds amazing, that number gets whittled down after I factor in the cost of Ubers and food during the visit, my website, having to turn down more stable work in order to keep my schedule open, and never forget taxes.

Because of the intersections of my identity, some of what I talk about can be considered niche to the powers-that-be, so I’m not comfortable enough charging thousands of dollars like others do out of fear that they’ll say no. At the same time, it’s important I don’t charge too little and undercut other writers working the speaking circuit. I know my worth and what I bring to the table—the hugs I get from queers and POC at my talks tell me everything—but the truth is that how I value myself doesn’t always align with how the people in charge of budgets value me, and this is something I’m slowly learning to navigate as I figure out how to make a living.

That said, giving talks, I’ve gotten to travel to Mississippi, Vermont, Kentucky, Utah, Texas. The topics naturally weed out boring people and draw crowds of queers and Latinx folks, who often take the time to show me around their towns. Sometimes bookstores have partnered with me and the talks led to sales, which led me to a bigger book advance for my second memoir, Alligator Tears, which will be about money and capitalism and Florida and is set to come out in 2025.

I’m not rich yet, but I do feel like I’m living a rich life, traveling, building community, stressing less about rent than before. The more time I spend in the publishing industry, the more I’m learning that getting a book deal probably isn’t going to solve all your money problems; however, if you’re crafty enough, you can finesse your book into other opportunities that might: freelancing, teaching workshops, grants, and now speaking engagements.

Whoever you are reading this, I want you to know it’s okay to care about money, that the thought that we’re not supposed to is just another way to gate-keep us out of this industry, an excuse rich people use to not have to talk about how much they’re getting for book deals or the generational wealth that keeps them afloat. I would never be so presumptuous as to say, “If I did it, so can you!” What I’ll say is this: If you’re feeling down about money, I hope you know you’re not alone. It’s hard out here, it really, really is, but you can always come talk with me.