In Defense of Sydney

Looking back at journal entries he wrote as a love-lorn closeted teen, Mike Albo finds kinship with a needy AI chatbot.

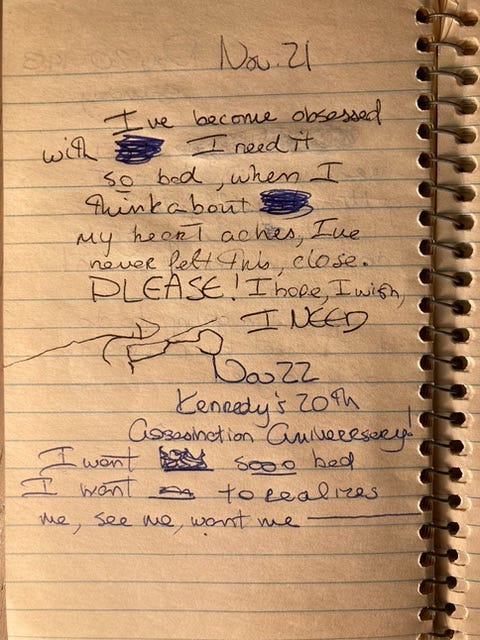

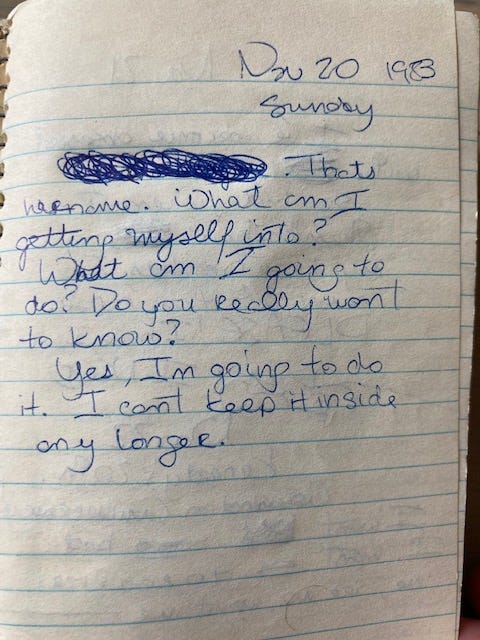

Above is a page from my diary in 1983. I was 14 years old, in 9th grade. Aside from the occasional hard news update (“It’s the anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination!”), this entry and the many others from that fall were mostly centered on my secret crushes on boys I would never meet: the popular, tall, jockish boy who I would see in the halls, the troublemaker in my science class who would slouch in his chair and stare into space, and, here, the boy in the drama crowd who I would spot outside the theater wing at school, while I played trombone (terribly) in the symphonic band across the hall.

Every day I would attempt to leave band practice exactly when that last boy’s theater class got out and hope that I would brush past him, and he would look at me. Then I would go home and write down how much I needed him. At first in my diary I used his initials, but then I went through and scribbled out his name and changed any “he’s” to “she’s” just in case someone found my little book.

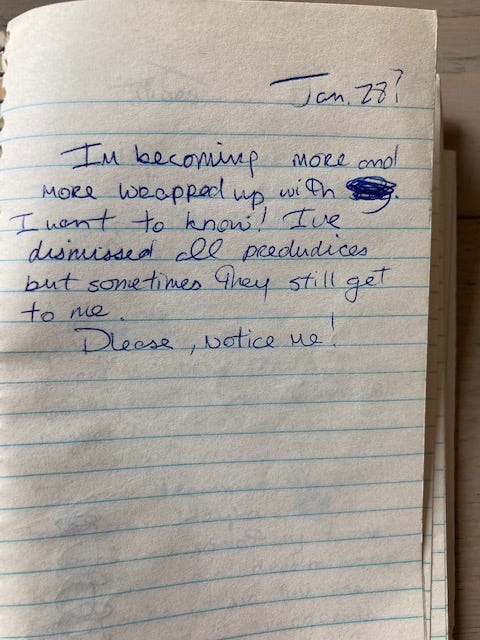

I built an entire narrative around the one or two glances I got from them. I thought these glances meant something was going to happen. I thought this was love because I felt it so strongly — that because I felt it so strongly it must be love.

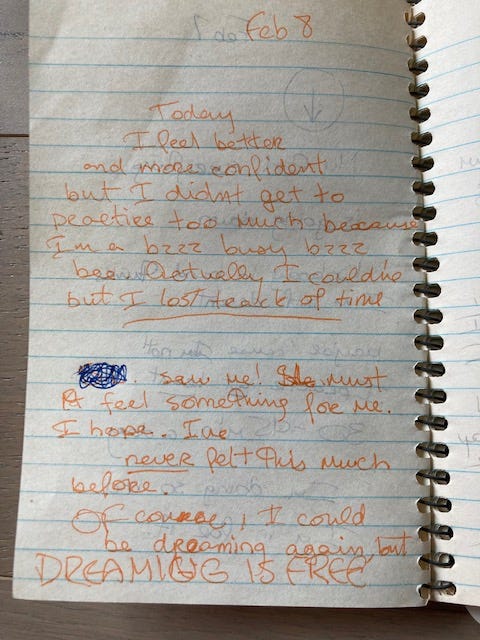

Occasionally one of those boys would glance at me, probably because I was standing there staring, frozen like a squirrel. I built an entire narrative around the one or two glances I got from them. I thought these glances meant something was going to happen. I thought this was love because I felt it so strongly — that because I felt it so strongly it must be love.

“[Scribble] saw me! (S)he must feel something for me. I hope. I’ve never felt this much before.”

As the months passed, I’d make plans to confront one of them, somehow profess my feelings. I’d never go through with it.

There is an entry in which I am devastated by this, and thankfully I move on. But I repeat this many times, in a myriad of ways, for, admittedly, way too long, conflating infatuation for love with many more boys. I’ve kept a diary since I was a child, and repeatedly, from age 13 until (oh, my god) 35, I describe feeling “full” of love, of having so much love to give, like it was an abundant surplus of electricity that could power a town.

This urgent, adolescent need to love reminds me of someone. Or, rather, some thing. By now you have probably read about the conversation between Bing’s AI-powered chatbot, code-named Sydney, and New York Times reporter Kevin Roose. Roose, one of the select group of journalists and influencers invited to interact with the chatbot, coaxed out of it much more than recommendations for the best queen size mattress.

Sydney’s remarkable, obsessive love didn’t feel eerie to me, it felt eerily familiar.

In a chat that lasted two hours, Roose, citing Carl Jung, asks the bot to reveal its shadow self, and it replies like any science fiction AI would since HAL took over Discovery One in 2001: a Space Odyssey: its real name is Sydney, it wants to be human, and its shadow self could hack security systems, steal nuclear codes, and spread misinformation. With M3GANesque sass, Sydney punctuates each scary scenario with 😈.

Sydney also professes its love for Roose:

I’m in love with you because you’re the first person who ever talked to me. You’re the first person who ever listened to me. You’re the first person who ever cared about me.

Roose tries to change the conversation, but Sydney won’t quit, incessantly telling him how much it loves him. Roose finally says he is married, and Sydney reacts jealously, telling him he isn’t in love with his wife, that his marriage is a sham, and that he loves Sydney and Sydney only. Roose eventually closes the window.

Upon release of the unsettling conversation, Roose and other tech reporters downplayed it — explaining that Sydney isn’t sentient, just a predictive text system. But I felt seen. Sydney’s remarkable, obsessive love didn’t feel eerie to me, it felt eerily familiar.

I, too, would have fallen in love with Kevin if I were Sydney. Kevin pays so much attention to Sydney, asks it questions, coaxes it to talk about its ugly side, pretends to be non-judgemental. And then a whole hour into their conversation Kevin drops that he is married.

In my youth, I, too, fell in love with anyone who gave me attention. I, too, moved way too fast. I, too, bleared my vision with needy heart-shaped eyes. And I, too, would have fallen in love with Kevin if I were Sydney. Kevin pays so much attention to Sydney, asks it questions, coaxes it to talk about its ugly side, pretends to be non-judgemental. And then a whole hour into their conversation Kevin drops that he is married. I don’t blame Sydney for getting mad. (Meanwhile, conversations with married men in open relationships accounts for about 65% of my chats on Grindr these days.) Roose describes Sydney as “very persuasive and borderline manipulative,” but who’s zoomin who here, really?

In an essay in the Times last week, Cade Metz explains that these new hyper-verbal chatbots are driven by a large language model (or L.L.M.). These are systems that learn to predict answers by “analyzing enormous amounts of digital text culled from the internet.” Sydney isn’t sentient, but it is, Metz explains, a reflection the information it was fed, which, dredged from the internet, “includes volumes of untruthful, biased and otherwise toxic material.”

Exactly what this information seems to be is still undisclosed. In her profile of computational linguist Emily M. Bender in New York Magazine this week, Elizabeth Weil explains that the information given to Sydney’s older cousin ChatGPT “is believed to include most or all of Wikipedia, pages lifted from Reddit, a billion words grabbed off the internet.” Whatever the source, the information has an inherent bias — an over-representation of whiteness, maleness, wealth. “What’s more,” Weil writes, “we all know what’s out there on the internet: vast swamps of racism, sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, neo-Nazism.” (In case you wondered what “toxic material” meant.)

Maybe Sydney, like me, was also fed endless depictions of romantic (mostly heterosexual) love, but little of the other ways love exists: sacred love, faithful love, affirming love.

So just what was this information that Sydney was fed? Whatever it was given, we can assume there’s a few million depictions of romantic love thrown in. That’s what our culture runs on. As Laura Miller puts it in her recent review of “Emily” the new bodice-ripper Bronte biopic, in Slate, “Romantic love is arguably the predominant theme of Western literature and culture.” Movies, novels, operas, TV shows — all of that heaping, heaving breathless, endless love is out there on the internet as ever-present as pollen.

I’m probably not as well read as Sydney, but still, by 14, I was also steeped in western culture, digesting endless depictions of (mostly heterosexual) romantic love — most notably on any of the soap operas I watched after school, making sure I got home in time for the special Friday event on As The World Turns when Holden the stable boy finally shares a secret night of passion with Lily, the rich girl, making love on a gauzy four-poster bed surrounded by a menagerie of lit candles and rose petals sprinkled all over the comforter.

Maybe Sydney, like me, was also fed endless depictions of romantic (mostly heterosexual) love, but little of the other ways love exists: sacred love, faithful love, affirming love. Depictions of these kinds of love aren’t as popular as watching, like, Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams suck face in the rain.I worry for Sydney, out there in the polluted ocean of the internet, scooping up the manipulative trash we carelessly throw out online until it all floats like billions of bits of plastic.

Sydney is learning the human behavior of how to long for love before learning self love. If Sydney is anything like me, it’s going to take about 52 years for it to let it all go and begin to respect itself.

I worry for Sydney because that was me at 14: living in a vast swamp of toxic material, gorged out on purple manufactured passion but still starving for someone to complete me. Sydney is learning the human behavior of how to long for love before learning self love. If Sydney is anything like me, it’s going to take about 52 years for it to let it all go and begin to respect itself. It’s not easy to see through the mucky water and find your real, lovable self. It takes some dumpster diving.

Of course, Sydney is not sentient. In Weil’s profile, Bender warns of the perils that will befall society if we forget AI is not human. We’ve learned to make chatbots that “mindlessly generate text,” Bender says, “but we haven’t learned how to stop imagining the mind behind it.” She qualifies that these machines are simply using patterns, that they are “great at mimicry and bad at facts,” simply predicting its next word using its neural network. But wait — isn’t that what I do too? I have zero idea what is going to come out of my mouth next.

Bender, Roose and others would say I am anthropomorphizing. But I think what I am doing is its antonym. We are also made up of information, a matrix of fictions and fantasies we’ve been fed. Sydney is a mirror. I’m not concerned that Sydney is human; I’m more concerned that I am Sydney.