Mirrors

In her 20s, Natalie Serber looked in the wrong places for the woman she hoped to become.

If it was just a shopping spree, why was I in tears? Alone in my old Volvo (a cassette player zip-tied beneath the cracked dashboard) I told myself I made the drive for the sale rack at I. Magnin. But really—lonely in my marriage, afraid of the future—I headed forty-five miles south through stubborn fog, past dusty artichoke fields, to posh Carmel with its lingerie-style marine layer, bits of sky-blue peeping through the mist, for the doting attention of the saleswomen.

It was 1984 and I was 22. Stepping through the glass doors in a moth-bitten vintage skirt and a shrunken sweater that revealed a sliver of belly when I moved my arms, my plastic Candies heels ground down from walks I took each night preferring the cool evening to the seat on the couch beside my husband, I entered a realm of elegance and calm. Piano music delicate as a souffle, thick carpet, gentle lighting, my shoulders relaxed. I breathed deeply the air perfumed with White Shoulders, or L’air du Temp, both out of my reach save for the tiny, plastic-capped vials handed out as samples.

It became a regular endeavor. I’d select a few garments from the sale rack, a Mohair sweater in July, sleeveless blouse and linen slacks in October, which a saleswoman deposited in a vast dressing room with what my diet-conscious mother would’ve called a “skinny mirror,” one in which you always looked inexplicably lovelier, livelier. I’d thought my marriage would be such a mirror, an upgrade from my real life, a shelter from loneliness. The saleswomen knew my size and often added more clothes for me to try on, things that needed dry cleaning, a pleated wool skirt, a jewel-toned silk blouse, a paisley scarf. All more Nancy Reagan than me—too short, too broke, too young. The women, with their chignons and powdered cheeks, buttoned, zipped, and held my hair off my neck as they gazed over my shoulder at my reflection and told me I was lovely. Had there been such a thing as online shopping, virtual carts to fill alone at night in front of my laptop, I’d have missed the saleswomen who tended to me like devoted Aunties, who showed me possibilities beyond the girl who’d walked through the doors.

When we were dating, my then husband-to-be told corny dad jokes, gave thoughtful gifts, paid our rent, and dealt cocaine. He was the perfect blend of stable and reckless. He adored my energy, my nimble body, my willingness to appreciate new things like sailing, folk music, raucous sex, and car maintenance.

Nineteen to his 33, I urged him to pop the question and he did, in a rowboat, which nearly tipped when I lunged into his arms. I said yes to him to be sure, but also yes to dinner parties, buying a couch on credit, a Cuisinart, all the things that felt grown-up and committed. These things had evaded my mother who, as a young woman in 1962, found herself accidentally pregnant and raising me on her own. She spent my childhood seeking security in a man, going out weekend nights to “find you a dad.” We moved thirteen times. I attended five elementary schools. When I was 16, my mother decided enough! She was done healing her once-again-broken heart. She bought her own house and consigned to sleeping alone.

I’d thought my marriage would be such a mirror, an upgrade from my real life, a shelter from loneliness.

Enough for me meant sleeping beside my solid-as-the-interstate husband every night. Enough meant not moving again. Enough meant feeling wanted. Enough meant never being lonely.

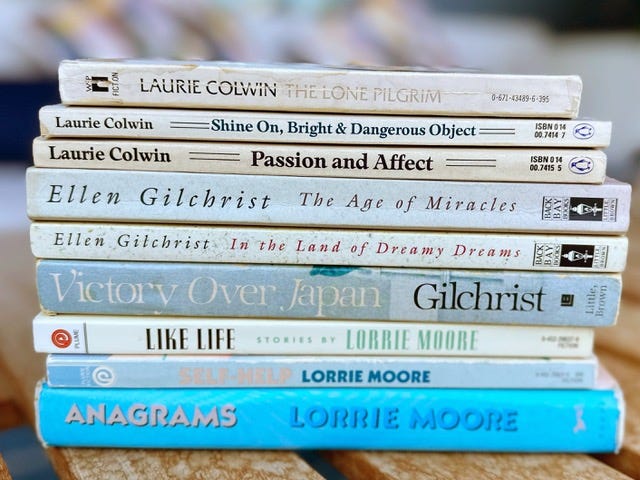

Until I was 22 and it wasn’t enough. One night I found myself cleaning the stove with a toothpick at three in the morning and decided to quit snorting coke. I transferred from community college to university and graduated with an English degree. I wore a beret, not ironically. My husband played the tuba, not ironically. I read Laurie Colwin, Lorrie Moore, and Ellen Gilchrist. I wanted someone to read beside me in bed, to have conversations about books, not watch Joanie Loves Chachi, snort a line, and mess around. The last thing I wanted to do with my husband was mess around. When he laughed his nose crinkled up so high I could see inside his nostrils. He hated my cool detachment.

One time he was late coming home and when he called to tell me he’d hit a deer, I didn’t realize I hadn’t asked if he was okay until he said, “Yeah, I’m not hurt.” The phone turned molten against my ear. He was not reflecting back a better me because I seemed to have misplaced my best self.

Another day, I entered our bathroom to find the Playmate-of-the-Month propped open on the sink—lips and toenails cherry red, everything in between round and creamy—a bottle of lotion and a hand towel on the lip of the tub. He blocked the door and said, “What do you expect?” I guess I expected not to be assaulted by his needs, which I was trying my best to ignore by sleeping with my back to him. I expected not to feel shame for not wanting sex with him. I expected to have the freedom to grow up. I expected him to be delighted in my burgeoning, like a parent would be, but he was not my parent. I had a mess of expectations. I wanted out and I didn’t want out and I didn’t know how to go about anything.

So, I drove south to shop at I Magnin. I don’t remember my conversations with the saleswomen. I remember feeling cared for, being cooed over. When they passed me the application for a credit card, I filled it out, and on the basis of my two jobs, aerobics instructor and waitress, I was granted one. I started to buy a few things—a small handbag, a cashmere sweater, too large and on sale, fuchsia lipstick in a chic case with a mirror. I purchased things for another life and when I got home, I put the tissue-wrapped parcels in the closet like a trousseau.

My husband took me skiing, something he’d done with his family and something I’d done once. When he deposited me atop a blue run, I remember being horrified by the drop-off. Angry that I’d trusted him to keep me safe and yet, poised in the wind at the top of the hill, I was not safe. A blue slice of lake glimmered in the distance. Snow sparkled in thin winter sunlight, there was a biting smell of pine from trees that cut a green river down one side of the slope. Skiers whooshed by me. My husband expertly pitched down the hill, cut an elegant turn to halt and wait halfway down, grinning up at me. I shivered. I cursed him, side-stepping over the lip.

I wanted out and I didn’t want out and I didn’t know how to go about anything.

This is not a story of me being brave and experiencing exhilaration. Skis fell off. Snow invaded my boots. I don’t remember words. I remember volume. All the fear and sadness I’d been stuffing poured out in an ugly rant full of spittle and declarations of hate—for the indoor/outdoor carpet in the kitchen, for him and his love of weak coffee, for the boring way we lived. I was vile. Abandonment was likely what I wished for—a way to leave the marriage that didn’t require action from me. On the way home, I lay in the back seat, a petulant child/woman, watching through the window as the sky turned from pale blue to determined blue. I was lulled by the tires, by the Kingston Trio on cassette, which I didn’t have the energy to hate. He woke me, gently shaking my shoulder, when we arrived home.

Women did not work in the shoe department at I Magnin. Perhaps the way the men straddled the shopper’s naked foot, tenderly cupping a heel like a beau was too intimate. When I found the peau-de-soie pumps on the sale rack, no Prince Charming salesman placed one on my foot. I dropped it to the floor and slipped my foot inside. A discreet peek-a-boo window below the bow made them more Audrey Hepburn than Nancy Reagan. I pivoted in the tiny foot mirror. They were nearly $70, the same as my car payment. I had nowhere to wear them, but the shoes, simple and elegant, seemed necessary. Yes, I’d added to my growing I. Magnin debt, and yes, I planned on becoming a woman who wore silk shoes.

And I did, around our apartment. I carried myself the same way I did at I. Magnin’s, taller, straighter. I hummed. I admired my feet when I sat on the toilet, washed lettuce, and made strong coffee.

After a bit he stuck his head out the front door. “You’re leaving me aren’t you?”…His words frightened and exhilarated me. “Yes,” I said, to him, but also to my future.

One Saturday I decided to change the spark plugs on my Volvo. My husband had taught me basic car maintenance: check the tire pressure, check the oil, change dirty spark plugs. I pulled my hair back in a ponytail, slipped into overalls. The hood was up. I had tools, ArmorAll and a whisk broom, Windex and paper towels. Taking care of my car, paying my bill each month, the clothes of my future in the closet, the stirring desire to become a writer, I felt independent and confident.

My husband watched from our living room window, one hand thrust deep in his pocket, the other gripping a mug. I leaned into maw of the hood, using a matchbook to measure sparkplug gaps, adjusting the tiny canyon for sparks to leap. After a bit he stuck his head out the front door. “You’re leaving me aren’t you?”

A light, a firefly really, hovered in my throat. His words frightened and exhilarated me. “Yes,” I said, to him, but also to my future.

I did not rush to my husband when he began to cry. That night he was gone. Of course it wasn’t the snowy tantrum, the Playboy, the peau de soie shoes, or the saleswomen who tended to me, who knew my size and showed me possibility. It was everything. It was time.

Yes, I was afraid—the specter of my mother’s half-empty bed was real. But that fear seemed more surmountable than the loneliness of the present. My husband did not reflect back a lovelier, livelier me, he reflected just me, another struggling human. If I required a mirror, I wouldn’t find it at I Magnin either, it would have to live inside of me.

I love your writing style! I liked the parallels you draw multiple times and the introspective nature of this slice of memoir. I'm writing one myself too - the story of my own divorce and how I found myself after it, so this resonated lots. 😉

Wonderful piece, thank you Natalie. Brought back memories of an earlier marriage.