What the Prior Tenant Gave Me

I owe my favorite decade in the city to a gore-obsessed artist who got evicted.

It was an apartment I once thought only a true New Yorker could love, with lopsided floors, rotting window sills, lumpy plaster walls, the world’s tiniest bedroom — seven by seven-and-a-half, just big enough for my full-size bed — and a bathroom in the kitchen.

I first looked at it on a brutal February day in the early 90s. There was a long line down four flights of stairs to see this “spacious” railroad apartment that had been advertised as a “two-bedroom” in the Village Voice.

At the end of the line, I figured I didn’t have a chance. But then I saw that the line was moving quickly — almost too quickly. When it was finally my turn to look around, I got to see why everyone else before me had left so abruptly, without even filling out an application: outsider artist Joe Coleman, the existing tenant who was being evicted, was there. And he was freaking people out.

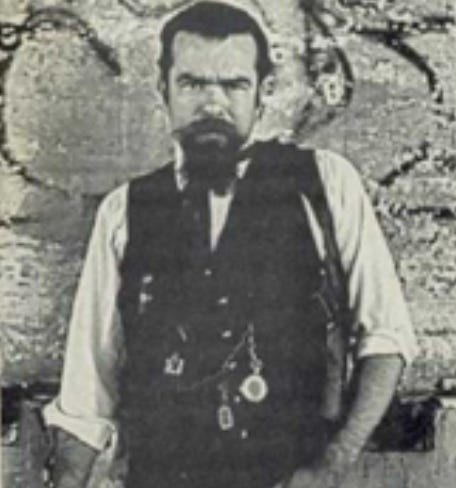

At the time, I didn’t know he was “outsider artist Joe Coleman,” known for painting the poster for Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer, and later the subject of a documentary, Rest in Pieces: A Portrait of Joe Coleman, narrated by Jim Jarmusch and others, and a coffee-table art book, Original Sin: The Visionary Art of Joe Coleman. I just knew he seemed a bit off, and maybe a little menacing. He was decked out in Civil War regalia and had long, wide mutton chop sideburns. He was missing some teeth, and was scowling, aggressively, at the realtor, from a corner of the kitchen – presumably not too happy about being evicted.

His place was freaking people out, too. It had a creepy feel. The cramped, closet-like space that was to become my bedroom was filled, floor to ceiling with newspapers and garbage. You couldn’t even walk in. The living room had thick, black velvet curtains, and the most curious things on display: a fetus in a jar; wax renderings of bloody, severed limbs; illustrations of people with their guts pouring out.

Still, I couldn’t imagine I was the only person who could see past all of Coleman’s gore to the exposed brick walls, the decent amount of overall space for one person, the low rent — $825, initially. But apparently I was; no one applied for the place but me.

Two weeks after I signed the lease, and before I moved in, I was stopped dead in my tracks by the cover of the Village Voice on a newsstand. Staring out from it rather eerily was Coleman, seated in the apartment’s living room — which he’d dubbed the “Odditorium” — accompanied by the severed limbs and “Junior,” the pickled fetus. The headline read, “Serial Killers and the People Who Love Them.” It turned out Coleman was famous for intricate folk art portraits of serial killers, and he had a cult following.

Not just that, but a cable access show, too, broadcast right from the “Odditorium.” On the show, he would bite the heads off of mice, and pretend to blow himself up, among other stunts.

When I finally moved in, I found the place hadn’t been renovated as promised. There was a massive hole in the sagging kitchen floor, many of the walls were peeling, and ceilings were buckling, threatening to collapse.

More curiously, though, there were jewelry boxes stashed in corners here and there. I nearly died when I opened one — it was a coffin for a dead mouse. I opened a second — another dead mouse. I quit at two, gathered them all in a garbage bag, and ran them down to the pails in front of the building as quickly as I could.

***

One morning four years after I signed the lease, the bathroom ceiling collapsed just as I was stepping out of the shower, a chunk of plaster grazing my head. There was still a gaping hole in the kitchen floor, along with all the other disrepair I’d been complaining about to no avail. The rent was now over $900 a month, which was a lot in the mid-90s, at least for me. That’s when a friend told me how to find out if you’ve been overcharged and take your landlord to court for “treble damages” — three times the amount you’ve overpaid.

As instructed, I requested a rent history from the New York State Division of Housing and Community Renewal's (DHCR) Rent Administration, and learned that Coleman had been paying just $234 for the place. The landlord had more than tripled that for my original $825 lease without making a single improvement, which was against rent stabilization laws.

I tried in vain to get in touch with Coleman to confirm the numbers. Then I saw that Rest in Pieces was going to be screening at Anthology Film Archives, and Coleman would be there. So I went.

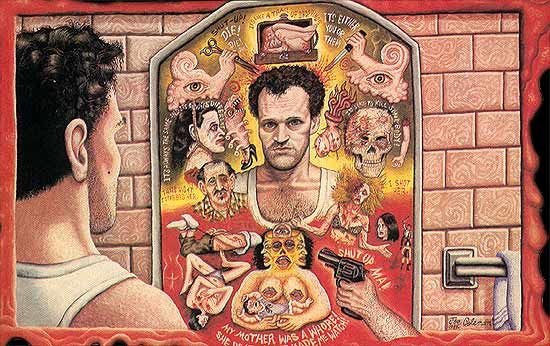

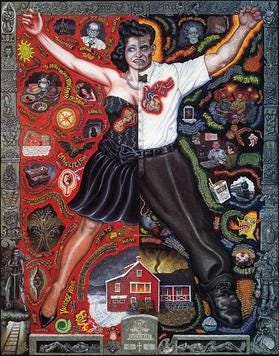

The film was fascinating. Coleman was a carnival character for sure, but also a serious fine artist who was obsessed with the darkest human tendencies. A few years later, Spin Magazine would refer to him as “Abnormal Rockwell.” He made these dark folk portraits of sinister figures, like serial killer and sex offender John Wayne Gacy. Surrounding the portraits were intricate renderings of details from their lives, with the tiniest captions.

When the film and Q&A were over, I waited in line to say hello to Coleman. When it was my turn to be greeted, I quickly told him that I lived in his old space, and had a few questions for him regarding my case against the landlord.

I found him in much better, friendlier spirits than he’d been the first time I encountered him. “Did I leave you any…uh…gifts?” he asked, rather sheepishly, referring, of course, to the mouse coffins.

“Yeah, thanks a million,” I kidded him.

“I’m sorry about that,” he apologized. “I did that to get back at the landlord since I was getting kicked out.”

He confirmed that his rent had been just $234. (He added that he’d been evicted because the lease had been in his ex-wife’s name, and once they were no longer married, he lost the right to stay there.) That bit of rent information was all I needed to persuade my landlord to settle the case, return $8,000 to me, and lower my rent to $633. (By the time I left, the rent had risen to $722.)

That night I became a fan of Joe and his art.

While I lived in that apartment, I did my best to improve the place without investing too much in it — I never thought I’d be there very long but in the end, I spent over a decade there. I painted it, found some decent furniture, kept it sparse.

What’s amazing to me is how, with almost no real structural improvements, my apartment’s stock went up significantly over the years. When I first moved in, friends and family questioned my choice to live in a “slum.” But a few years later, just about everyone wanted to be notified if I had any plans to give it up so I could sign the lease over to them. Other units in the same line, which turned just about every semester, soon crept up to about $2,100 — each filled with three NYU students, or recent grads.

The rents just kept rising from there. Most recently, my unit went for $3700.

In the years that I lived there, it never occurred to me to give the place up, and not just because I psychic had told me, circa 1993, “I’m hearing the words, ‘Don’t give up the apartment.’” Eventually I came to assume I’d have it for life.

But then I met my husband, Brian. When we got engaged, we briefly considered sharing my run-down fourth-floor walk-up to save money, but instead opted to kick his roommates out and take over the under-market-value, three-bedroom duplex loft in a beautiful historic building that he’d lived in for many years, on Tompkins Square Park.

A month after we gave up my place, though, we found out we were losing Brian’s. A year in housing court later we won the case (for $1,000 less than our legal fees), but lost the apartment. We were completely fucked. Unable to afford so much as a studio in Kew Gardens for the $1,350 we’d been paying (plus some cash on the side the landlord had begun requiring), and uninterested in moving to the suburbs, in 2005 we relocated two hours north, to the Kingston area of the mid-Hudson Valley.

***

One summer weekend a couple of years after moving upstate, we stayed at a friend’s West Village apartment and went to breakfast at La Bonbonniere, a greasy spoon institution on Eighth Avenue near Horatio Street. Seated next to us was a heavily made-up woman in her late 80s who wasted no time striking up a conversation.

She seemed to be one of those lonely New Yorkers who spend so much time by themselves that as soon as they come into contact with other humans, they start babbling, almost involuntarily. I’d once been terrified of becoming one of them.

The woman, a onetime musical theater actress, asked us where we were from, and we somehow wound up on the topic of the tenement apartment I’d let go. “I still sometimes kick myself,” I said.

“Listen to me,” she insisted, “a rent-controlled apartment can be a life sentence! I’ve been in my place for over sixty years, and it has kept me from many other things in life.”

She said she’d forgone yearlong U.S. and European tours with musicals, for fear of losing her studio—now $150—if she’d sublet it. The place wasn’t big enough for two, and anytime living with someone or getting married was on the table, she felt too shackled to her low rent to take a chance and move out. There had been two broken engagements. She was filled with regret.

“You made the right choice letting it go,” she said. I can never be 100% sure I did.

Wow, that's a New York story if ever there was one! Beautiful.

Not only a remarkable only in New York story but a testament to the gutsy, fearless gal you are! AMAZING!