On Rejection

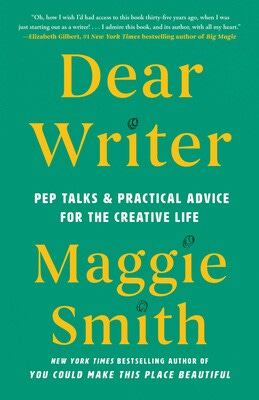

An excerpt from "Dear Writer: Pep Talks & Practical Advice for the Creative Life" PLUS a brief video interview with Maggie Smith about the book.

Once upon a time, when I first began submitting poems to journals, rejections arrived in the mail. They were often on colored strips of paper inside a self-addressed stamped envelope you’d sent with your poems and cover letter. Yes, the handwriting on the envelope that contained your rejection was your own. Yes, that felt strangely intimate and complicated.

The strip of paper inside was certainly a no. Sometimes the strip was so narrow that ten or twelve rejections were likely cut from one sheet of paper. Some were hardly larger than fortune cookie slips. How economical!

If the envelope felt thick enough to include a full sheet or two of paper, it might be a yes. But not always. It might have been a no printed on a full sheet of paper—the luxury!—and a sheet of paper advertising the magazine’s next contest.

If you were lucky, there was a note scrawled in ink on the strip of paper or the bottom of the letter: Close or Try us again or We liked these.

Like many writers, I kept my rejections like battle scars. A few I tacked up; others I filed away. My graduate school friends and I joked about decoupaging coffee tables with them. (You could put your feet up on the rejection table. You could set your drink down, no coaster needed.)

These days a rejection usually arrives as an impersonal email, one an editor must select from a drop-down menu in the journal’s online submission system. Working for a literary magazine—like judging book contests—has helped me to see rejection in a new way. I know how much stunning, worthy work is out there, and I know how little room we have to publish it. The decisions are sometimes excruciating. A no is a subjective no to one specific batch of work at one specific moment in time by one particular reader for a variety of reasons.

It bears repeating: A no is not a rejection of you. It’s not even a rejection of your work as a whole, or your worth as a writer. It’s not a no to your talent.

I also want to say this about rejection: Every no makes room for a yes.

Picture your CV or résumé: it’s a few pages (or many pages, if you’re a longtime academic) of accomplishments, experiences, and awards. It’s all of the yeses in black and white. Now imagine

if you had a CV or résumé of every no you’ve ever received: every job or promotion you didn’t get; every rejection from an editor or publisher; every grant, award, or fellowship you didn’t land.

That’s your shadow CV, and it’s many, many pages longer than your actual one. Each of us has racked up many more noes than yeses, and those noes are often invisible to others. In the shadows.

We may not share them, but they’re there.

Or, to use another metaphor: Your CV is the tip of the iceberg we can all see above the surface; your shadow CV is the enormous portion underwater, unseen. I want us to acknowledge the size of the iceberg under the water, the length of the list of noes. It could sink a ship. It won’t sink mine. It won’t sink yours, either.

I tell my students about the long road to publication. I tell them that almost all of my poems were rejected, often multiple times, before they found a home at a magazine.

Before Meryl Streep read “Good Bones” at Lincoln Center, before the poem was featured on an episode of Madam Secretary, before it went viral and was read by millions of people, before it was published by the online journal Waxwing, “Good Bones” was rejected by a few other magazines. I sent the poem out to a few print journals I admired, and it was rejected by all of them. (No, I’m not naming names.)

Sometimes you don’t know that a loss isn’t a loss, because what it makes space for is better—a good reminder for all of us working on creative projects, putting ourselves out there, trying, and then trying again. My point is this: I didn’t know it at the time, but those early rejections were a gift. If “Good Bones” had been published in one of those print journals, it wouldn’t have gone viral.

By talking about and normalizing each no—each misstep, failure, disappointment—we remind one another that no one succeeds all of the time, and certainly not quickly. We’re all playing the long game, and the only way to fail at the long game is to give up. To refuse to play.

In Keep Moving, I wrote, as a pep talk to myself, let me remind you: “Think about geologic time: how the slightest shifts, imperceptible daily, carve canyons and make mountains. Trust that you are making progress even if you can’t yet see it. Keep moving.”

To say it another way: There are many paths in the creative life, and none of them is the autobahn.

Here’s some good news, too, from Maya Angelou: “You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

Recently a friend of mine brought something remarkable to my attention: Violets create a second set of flowers that remain underground for the life of the plant. These flowers are cleistogamous—fully closed, self-pollinating. They don’t contain chlorophyll or engage in photosynthesis, but they mature and set seed. What does this have to do with writing? Growth isn’t always visible. Sometimes the most essential work we do goes unnoticed, in dark and quiet places. And sometimes the failures clear a path for something better.

I totally do this — the list of rejections. I’m always a little excited to add to my spreadsheet a new rejection. It means I can add to my list. It makes me feel more experienced.

Academics share these experiences, including automation, except that we normally get referee reports on how bad our papers are. "Desk rejections", where the paper is sent straight back are less common.

Having been a prolific writer of journal articles for most of my career, and being located outside the charmed circle of high-status US universities (where you can shop your article around before submitting it), I've accumulated hundreds of rejections. I once got three rejections in one day.

As Maggie Smith says, you need to learn not to take this personally. One thing I have learned to do is to think "if/when this journal rejects me, here's the next one I will try"