Please Wait

The flicker of hope that kept me alive, courtesy of Morrisey.

Concern warning: suicidal ideation

Sissy Thompson and I played husband and wife every day after we got off the bus in kindergarten. I was the construction worker, off to some imaginary job site, while Sissy stayed home, cooking, cleaning, and waiting for me to return. It was a boring game—one I'd much rather have swapped for Legos or a Star Wars adventure with my brother—but there were two things that made it worthwhile.

The first was the kiss goodbye before I went to work. The second? The kiss hello when I came home. Those moments made my heart race, the rest of the game fading into the background. I never wanted it to end. But it always did, too soon, when Sissy had to go back to her house.

One day, we were sitting on her pink canopy bed, and I was secretly hoping for another kiss. Instead, she asked, “You want me to show you what my parents do?”

Before I could even process the question, she got on top of me, moving her body in a way that sparked something intense and exciting I had never felt before. I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to do with all of the overwhelming feelings that were stirring inside me. I lay there, frozen, unsure of what I was supposed to do or say and trying to appear calm.

“Husband and Wife” with Sissy was a boring game—one I'd much rather have swapped for Legos or a Star Wars adventure with my brother—but there were two things that made it worthwhile. The first was the kiss goodbye before I went to work. The second? The kiss hello when I came home. Those moments made my heart race, the rest of the game fading into the background.

When she finally stopped, she asked, “Do you like it? It’s called Hump.”I didn’t know what to say. How was I supposed to feel? Was this a trick? While I contemplated my response I tried to play it cool. Appear nonchalant. But, inside, my thoughts were screaming, “ARE YOU FUCKING KIDDING ME?! HELL YES, I WANT YOU TO DO THAT AGAIN! I WANT US TO DO HUMP FOR THE REST OF OUR FUCKING LIVES!”

But, I was too scared to say it. I settled for a neutral, “Um, I don't know,” like she’d just shown me her grandfather’s stamp collection.

Sissy moved away after kindergarten, and without her, I felt lost. There was one mild kiss with another girl, Grace, in first grade, but it was nothing like what I'd felt with Sissy. As I grew older, it became clear this wasn't a phase. But it also became clear that being different was dangerous.

Sometimes, when my mom took me to McDonald's for lunch, I’d see a woman there. I sensed I had something in common with this lady. She wore a mechanic’s jumpsuit, which admittedly, I loved. But, she also let her upper lip hair grow wild. I didn’t want to look like that. Somehow I already knew that being her, that being me, it made people angry.

The first time I learned what a lesbian was, I was home sick from school, watching Donahue. The show featured lesbians. I watched in horror as people shouted with an untethered rage, “Why do you have to advertise it? It’s not natural!” The audience confirmed my instinct. We didn’t just make people mad, we made them ruthless.

By fourth grade, I was hiding in daydreams. In one, I imagined Laura, my sister’s friend, watching me as I pulled off a slam dunk at the buzzer. In my fantasy, my teammates carried me on their shoulders, across the basketball court, all the way into Laura’s arms. “Julie Novak," she would say as we embraced and locked eyes, "you’re my hero!” I always wanted to be the hero.

But reality always had a way of yanking me back. One day, the doorbell rang. My mom called up to me from downstairs, “Julie, it’s for you! Remember your old friend Sissy?” Turns out she’d moved back to town. My heart leapt. Could it be that she remembered our secret? Was she different too?

We walked around the block, catching up, and I decided to test the waters. “You know,” I stammered, “I had a dream that I was kissing a girl.”

The first time I learned what a lesbian was, I was home sick from school, watching Donahue. The show featured lesbians. I watched in horror as people shouted with an untethered rage, “Why do you have to advertise it? It’s not natural!” The audience confirmed my instinct. We didn’t just make people mad, we made them ruthless.

Her reaction hit me like a punch to the gut. “But you’re a girl! Gross!” The shame was immediate and crushing. I wished I could take it back, bury the words I had just revealed. I knew then I’d never be with a woman. I’d never find anyone like me.

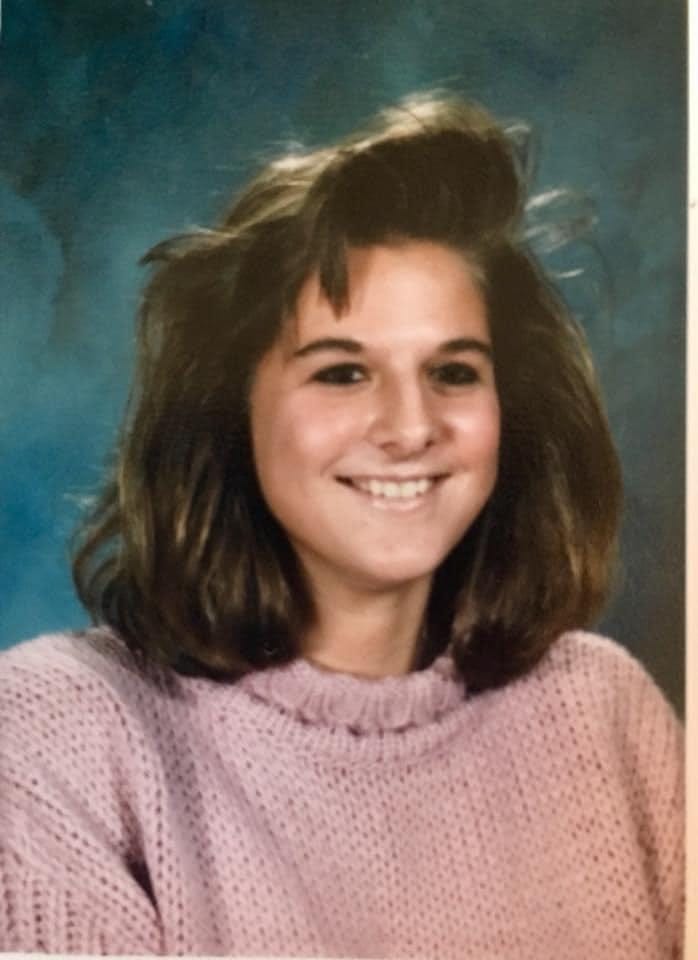

In seventh grade, I hit a wall. I was exhausted from pretending to like boys, from trying to fit into a mold that never fit me. I stopped wearing makeup, dropped the jelly shoes and the Zinc Pink lipstick, and rejected the boys who were interested.

That’s when the backlash began. Mike and Alex, boys I’d turned down, started calling me a “stupid bitch.” Dan Zagarro stuck his finger in my face and sneered, “Now that is ugly.” There was nowhere to turn, no place on Earth where I could be myself.

Music became a lifeline. The first time I heard The Smiths on the college radio station, and a melancholic voice crooned, “Will the world end in the nighttime? I really don’t know,” I felt seen. I wasn’t alone in my misery. Morissey was with me now.

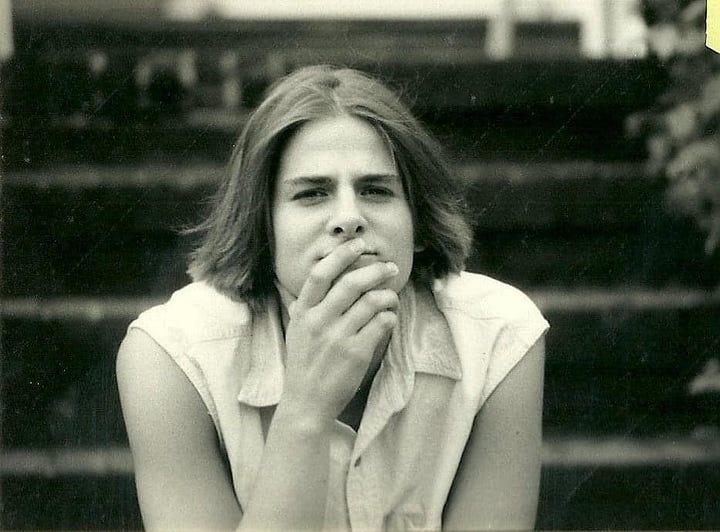

In eighth grade, I found a new group of friends who loved the same music I did. Carissa McCloud was one of them. She was everything I wished I could be: confident, smart, with an asymmetrical haircut that screamed rebellion. I was in awe of her.

On our school trip to Williamsburg, I found a way into her circle, grabbed hold and did not let go. For the rest of the trip, Carissa and I were inseparable. We shared a bed, stayed up late talking about everything—our families, school, music. We held hands and sometimes just looked into each other’s eyes, the air between us electric.

I was sure I was falling in love.

There was nowhere to turn, no place on Earth where I could be myself. Music became a lifeline. The first time I heard The Smiths on the college radio station, and a melancholic voice crooned, “Will the world end in the nighttime? I really don’t know,” I felt seen. I wasn’t alone in my misery. Morissey was with me now.

On the bus ride home, I sat next to Carissa, our shoulders touching. I had never felt more content, more alive.

And then, out of nowhere, she said it. “You know, I can’t wait to get home and see David. We started going together about a week ago. He would think you’re so funny.”

Another punch in the gut. Another blow that knocked the wind right out of me. All those late-night conversations, the hand-holding, the looks—they meant nothing to her. I turned to stare out the window. My eyes stung as I tried to hold back the tears. The lump in my throat felt suffocating. I had no future with her. I had no future with anyone who could ever truly love me back.

As the bus rolled on, I made a decision. That summer, when school was out, I’d end it all. There was no place in this world for someone like me.

I put on my headphones. Morissey was there for me. This time it felt like he channeled a message from God as he whispered in my ear:

My love, wherever you are

Whatever you are

Don't lose faith

I know it's gonna happen someday

To you

Please wait

Please wait

Oh

Wait

Don't lose faith

You say that the day just never arrives

And it's never seemed so far away

Still, I know it's gonna happen someday

To you

Please wait

Don't lose faith

It was a flicker of hope that kept me alive: a belief, however fragile, that somewhere, someone like me existed.

Ouch -- Julie puts into words how terrifying it can be to feel different at your core as a teen. Morrissey is so problematic these days, but back in the day, he saved my life, too.

I always feel honored when someone tells me honestly and courageously what being alive is like for them. Life is such a ball of mercury, isn't it?