Private Storm on Black Mesa Landscape

Jean Iversen looks back on a trip she took before she began an MFA program in her 50s.

A secluded resort in New Mexico seemed the perfect place to escape before I began a three-year MFA program in Chicago in 2019. At 53, after 30 years as an editor and communications manager, pursuing creative nonfiction writing was a now-or-never endeavor. I knew that once I entered the program, there might not be another chance to be this quiet for months, maybe even years, as my money and schedule would be bound tightly to this long-held dream.

I planned to do little else during my four-day trip except explore the resort’s 70 acres. But there were two places I wanted to visit in nearby Santa Fe: the Meow Wolf exhibit and Georgia O’Keeffe museum. The forecast threatened a storm for day three, so I got into my rental car and headed to the museum.

On the drive from the resort in La Cienega, I hit I-25 and found myself surrounded by nothingness. Almost no other cars were on the road. There were no exit signs. No traffic lights. Not even a billboard obscured the landscape. Just miles of reservations dotted with sparse shrub, stretching into more miles of flat land under a late August sun, the silhouettes of mountains waiting patiently in the distance. The landscape’s starkness was in sharp contrast to my life in downtown Chicago. Its silence surrounded me, startling me with its presence.

At 53, after 30 years as an editor and communications manager, pursuing creative nonfiction writing was a now-or-never endeavor. I knew that once I entered the program, there might not be another chance to be this quiet for months, maybe even years, as my money and schedule would be bound tightly to this long-held dream.

As I drove, dark clouds started to roll across the open sky, announcing the forecasted storm. I pulled over to the shoulder to take a few photos before it got too close. As I got out of the car, I took in the vastness, this private storm mine and mine alone to witness. The last time I felt this removed from civilization was 60 feet below sea level on a night dive under a full moon in my late twenties. Even then, I was in the company of a dozen other divers witnessing the same wonders, my boyfriend’s gloved fingers laced with mine as bioluminescence trailed our movements in the water.

What makes this desert scene so beautiful, I wondered as I stood on I-25’s shoulder taking photos, surveying the grays and faded greens all around me. No fuchsia or marigold to punctuate the asphalt. No lushness of trees to feed the earth. Not even a bird stirred the sky. Just flat, endless, and open. Something told me this brand of solitude was a rare, precious gift and might never come again. As my private storm surged closer, threatening lighting and a deluge of rain, I reluctantly climbed back into the car and drove on to the museum. It was the most alone I’d ever been in my life.

***

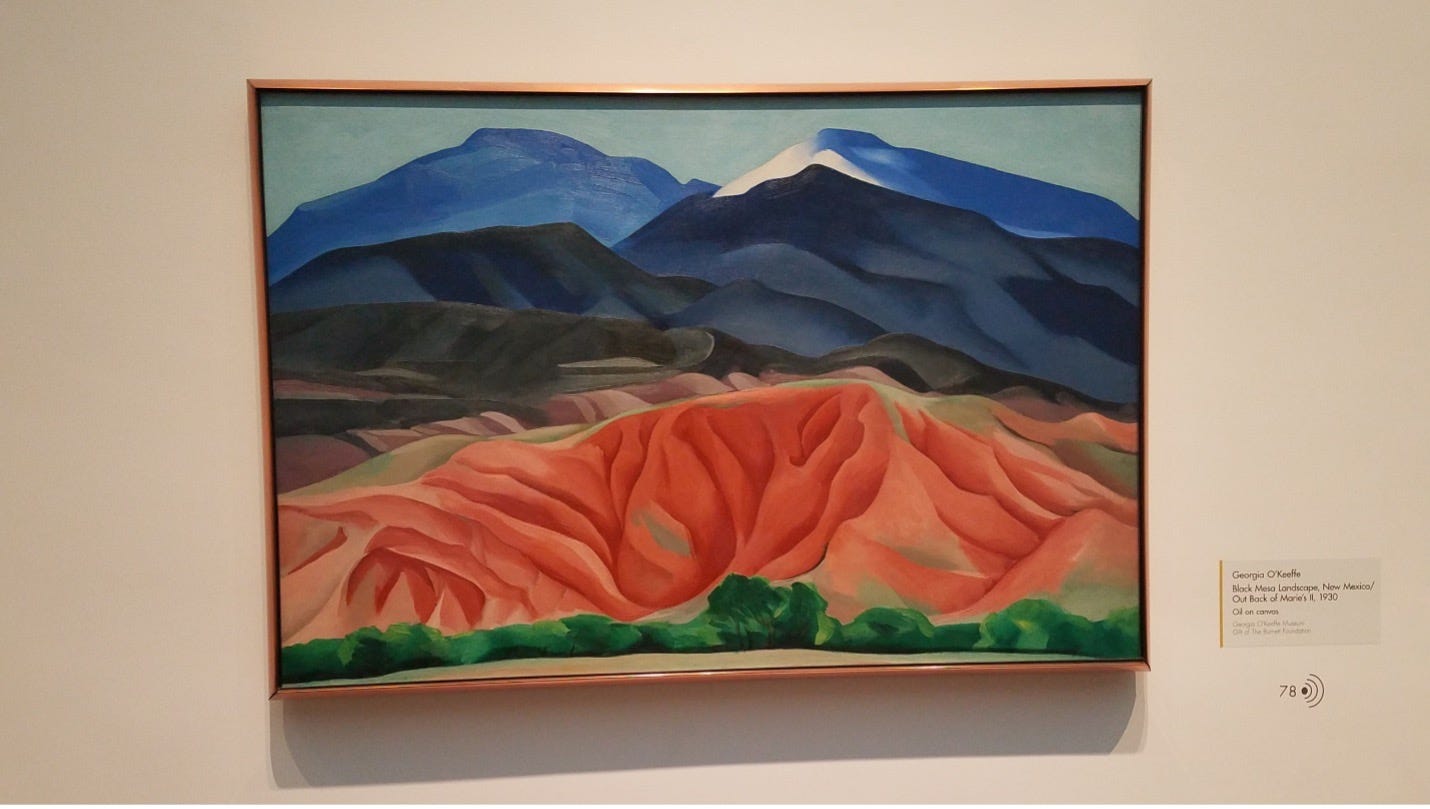

The moment I entered the Georgia O’Keeffe museum, I immediately connected the artist’s inspiration with the local terrain. O’Keeffe interpreted the surrounding hills, rocks, shells, and bones into abstract oil paintings and hundreds of other works using the palette of the Southwest. As I sauntered through the galleries, I was immediately drawn to “Black Mesa Landscape,” an oil on canvas the artist completed in 1930. The muted pinks and blues in “Black Mesa” echo this palette, as though faded by the fierce desert sun itself. The painting offered the same stillness and awe I had felt on the shoulder of I-25.

The Southwest is unlike any other place I’ve ever visited. It’s a strange, subdued region filled with echoes. It’s a place to confront the not-yet-confronted. To speak with God or question a god. It’s a setting that helps shine a light on the things that normally sit in the recesses of the mind, to consider decisions not yet made or trusted.

The documentary “Georgia O’Keeffe: By Myself” was playing on continuous loop in a small theater at the museum. I sat down to watch. “As soon as I saw it, it was my comfort,” said O’Keeffe about her first trip to Santa Fe. “I had never seen anything like it before. There’s something in the air. It’s different. The sky is different. The stars are different. The wind is different.”

I stared at the screen, suddenly lost in my thoughts about going back to school in my 50s. Even though I had already accepted the program’s offer, registered for classes, and been hired as a teaching assistant, doubts poked at me. I’m too old to do this. What if everyone else is a recent undergrad and I have no one to relate to? Can I really justify deferring my career for three years? Who am I to pursue this thing called creative nonfiction writing?

Back at the resort, I continued to obsess about going back to school and worked myself into a lather. Who would help put my mind at rest? My friend Sherry had recently completed a healthcare degree at the age of 50; she never seemed so happy as she was in her new job as a radiology tech. I wondered if she went through the same ordeal at the beginning. I dialed.

“Jean, I felt like a loser going back to school.” I couldn’t believe the words out of my friend’s mouth. Loser? Sherry was smart, well-educated, beautiful, and one of the most grounded people I knew. She had always presented herself with confidence and was often my touchstone for reason in the 25 years we had known each other.

I was instantly relieved and grateful for her words. Sherry hit the nail on the head as she described her mindset heading back into the classroom. How it felt like starting all over again, back to a beginning. Back at the bottom rung of another ladder, unsure of how long it would take before earning a decent salary. Sherry had three kids in school and was newly divorced. I had always admired her strength, but I found even more respect for her, considering the precariousness of her situation.

I pressed for more details, hungry for continued assurance. “How’d you get through it?” I asked.

“There were other students in all stages of their careers, some older than I was,” she said. “Keep your eye on the prize and you’ll get through it great.”

Even though I had already accepted the program’s offer, registered for classes, and been hired as a teaching assistant, doubts poked at me. I’m too old to do this. What if everyone else is a recent undergrad and I have no one to relate to? Can I really justify deferring my career for three years? Who am I to pursue this thing called creative nonfiction writing?

It comforted me enormously to know Sherry had also felt this way at one point. Beginnings are always terrifying, but this one seemed to rattle my nerves more than I expected.

That night, I sat outside on my deck at the resort, soaking in a sky thick with stars, one of New Mexico’s precious resources. Late August was considered off-season, and few other guests were in sight.

O’Keeffe painted until her eyesight failed her at the age of 95. I knew I couldn’t continue to work 10-hour days in an office, unless I wanted to spend every day with one hand on the door until I retired. Or sing in rock bands—my part-time creative outlet for over 30 years—until I’m 95. But if I could eke out a living writing and teaching until my body or my mind fails me, then this long-awaited decision was the right one.

There weren’t any replicas of “Black Mesa Landscape” at the museum gift shop, so I purchased a poster of “Red Hills and Pedernal,” the next closest thing. Back at home in Chicago, the framed poster hangs in my new writing space. It reminds me of the quiet of that desert, a place I know I’ll return to when I need to be still. When I need to feel the spaces, in between the echoes.