Real Estate

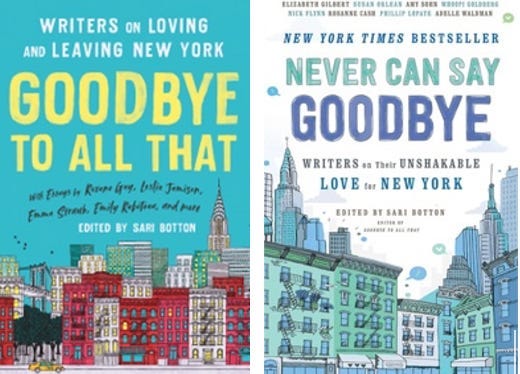

An excerpt of Goodbye to All That: Writers on Loving & Leaving NY

By

“I’m hearing the words, ‘Don’t give up the apartment.’ ”

It was my first of what would eventually add up to ten yearly appointments with Sophie, a psychic who was popular among media types—a ritual I’d later refer to as my “annual checkup.”

We were seated in the run-down, rent-controlled sixth-floor walk-up Sophie herself had held on to for twenty-odd years at the corner of Mott and Prince Streets. In the fall of 1993 that neighborhood was still considered Little Italy. It would be another few years before realtors would rebrand it as “Nolita.”

Petite and tomboyish in her forties, Sophie sat across from me at a table strewn with tarot cards, alternately flipping them and pushing back her little-girl bangs with the heel of her hand.

“Yes, that’s definitely the message,” she said, after closing her eyes for a moment. “Don’t give up the apartment.”

Well, no shit, I thought. I had a lease on a marginally decrepit but livable rent-stabilized one-bedroom in a tenement on East 13th Street, for which I paid about $600 a month. I didn’t need a clairvoyant to caution me against relinquishing it.

Besides, real estate advice was hardly what I wanted for my $150. No, I wanted Sophie to tell me what most people go to psychics to hear: that there was love on the horizon.

***

I was 28, two years out of an ill-considered marriage I’d entered at 23. Add to the usual difficulties associated with finding love in New York that I was a bit of an odd bird, difficult to match. All my life I’d been a strange mix of loner, social butterfly, and musical theater geek, sometimes painfully shy and awkward around people, at other times charming and entertaining. I felt like some kind of alien, out of step with the kids I grew up with (even fellow theater geeks thought I was weird), my classmates in college, and my coworkers at the assorted publications where I worked over the years. I didn’t like the same clothes, hairstyles, movies, music, and food that most of my peers did, and I had this insistent need to do most things my own peculiar way, even if it made no sense.

Not only would a man in my life have all that to contend with, but he’d also have stiff competition for my attention from the city itself. My idea of a good time—pretty much the best time—was walking leisurely around Manhattan and Brooklyn from neighborhood to neighborhood by myself, with no particular destination or goal. I preferred it to doing just about anything with anyone.

“I’m hearing the words, ‘Don’t give up the apartment.’ ” Sophie the psychic said. Well, no shit, I thought. Besides, real estate advice was hardly what I wanted for my $150.

Walking the city aimlessly alone had been my favorite activity since I was fourteen. I got the idea after some older camp friends brought me along for an afternoon of simply kicking around, mostly in the Village. That day, New York City transformed for me. It stopped being some kind of Oz, the fancy place where you went to see Broadway shows, the Little Orchestra Society at Lincoln Center, my singer dad’s operatic concerts, and all manner of culture with a capital C. This New York, the one my friends showed me, was a different kind of exotic. It was gritty and real; a place to take your time and people-watch; a place where what was happening outside, in the streets, on the sidewalks, in the parks, was the main attraction.

Soon after that day, for the first of many times, I lied to my mother the way other girls lied about hanging out with boys, telling her I was taking the Long Island Rail Road only four stops to see a friend in Lynbrook, but instead riding all the way to Penn Station so I could wander the city for hours, as far as my babysitting money would take me. I would sip hot chocolate as I observed the skaters at Rockefeller Center. I’d eat soup in Chinatown and observe the other “bridge-and-tunnel” diners in from the suburbs as they greedily inhaled their spare ribs and chow mein. I’d browse vintage clothing stores in the West Village and hang around Washington Square Park so I could observe the buskers around the fountain and the colorful, loud tourists cheering them on. I liked to observe non-loner-alien people, and New York City was the best place to do that.

The bonus: I could do it all without having to ask my mother to drive me from place to place as I had to on Long Island. Here, on foot, I was free. Wherever my feet took me, I was happy to have the city as my sole companion. I loved the feeling of being alone but among people.

I was horribly lonely and wanted to find that one other outsider who was put on this strange planet just for me—one who would, of course, give me plenty of space for my loner activities. So far, I only knew how to get that from guys who were difficult to pin down, emotionally withholding, and typically addicted to at least one substance, which is to say even less available than I was. Say what you will about unavailable guys, but you don’t run the risk of making them feel neglected when you want to do your own thing.

The preference for my own company naturally made it difficult to couple up too comfortably as an adult. I was horribly lonely and wanted to find that one other outsider who was put on this strange planet just for me—one who would, of course, give me plenty of space for my loner activities. So far, I only knew how to get that from men who were difficult to pin down, emotionally withholding, and typically addicted to at least one substance, which is to say even less available than I was. Say what you will about unavailable men, but you don’t run the risk of making them feel neglected when you want to do your own thing. Dating them so I wouldn’t feel hemmed in turned out to be a faulty strategy, though, because they drained me of my psychic energy—when they were around and when they weren’t—so I never really got to be alone when I was alone, and when we were together, I was never fulfilled.

As for nice, available guys, I seemed to be utterly allergic to them as mates but great at being friends with them. And so I introduced all my male friends to female friends. When the second of three couples married, they dubbed me “The East Village Yenta.”

The matchmaker had no talent for setting herself up, though. This job I’d have to outsource. That’s where Sophie came in.

***

“I see the letter B,” she said in her flat western New York accent. “Hmm. Who could that be? Pick nine cards.”

When I was done choosing, she shifted the cards around into different formations. “Okay. So, this person whose name begins with B. He’s got a goatee, maybe? I see him in a room with sharp angles, and a buffet with really mediocre food.”

For years afterward, I would scrutinize intently the “angles” of one mediocre-buffet-filled room after another to determine whether they might in fact be “sharp.”

Just then Sophie’s cat jumped onto the table. “Oh, Edie,” she said, stroking her. “You know what this means?” No, I didn’t. “When she climbs on the table during a reading, it’s usually a sign of true love. This guy with the letter B—this could be something! Yeah, look at that: the nine of cups,” she said, pointing. “That card can mean marriage. You might have a marriage to a guy whose name starts with B.”

Oh, great. I’d just divorced a guy whose name started with B. There went $150.

It’s a wonder I went back a second time, a year later. At that first appointment with Sophie, I didn’t yet know about the strange, random accuracy of at least some of her predictions—like the suggestion I keep my eye out for a good job offer from “someone named Horace—no, Horst” three years before I’d receive an assignment to ghostwrite a book for a guy with the unusual name of . . . Horst.

Incidentally, a three-year gap between a prediction and its coming to fruition was relatively short in Sophie-time. As she explained, “What I see here could happen in ten minutes, or ten years from now. It’s all very Agatha Christie. I’ll hear a name, or I’ll see an article of clothing, and ten years from now you’ll go, ‘Oh, my God—there’s that guy with the red shoes Sophie was telling me about!’ And he might not actually be your guy. But you can bet he will have something to do with your guy.”

Ten minutes or ten years? Couldn’t she pinpoint the timing of her predictions just a little more accurately?

“But time isn’t linear, dear.” Whatever that meant.

***

I was also eager to hear from Sophie whether there was a career break in my near future—some high-profile writing job or assignment that would both pay out and put an end to my six years languishing in the humdrum world of trade magazines. I’d wanted to be a writer living in New York City since I was a teen, after my grandparents took me to dinner at a restaurant in the East sixties and I spotted a woman eating by herself, with a notebook and pen as her only companions. I’d already been writing since I was in grade school. (I won the school-wide essay contest two years in a row.) But that woman writing and eating by herself put images in my head of a writing life located specifically in the city.

Not included in those images, to the best of my recollection, was one of me toiling endlessly at trade magazines with names like Body Fashions/Intimate Apparel, Fashion Jewelry Plus!, and Home Furnishings News, at the last of which I grudgingly covered the most bizarre assortment of beats: luxury linens, decorative pillows, air purifiers, and car alarms. I was always flying out from LaGuardia to housewares trade shows in Vegas and Chicago, where I’d moderate panel discussions on such exciting topics as whether HEPA air filtration was more or less effective than ionic particulation. I put in long hours at my desk, lunching and sometimes dinnering on salty soups and flavorless packaged salads from the nearest Smiler’s deli in the bland, sprawling corporate park that is much of Midtown. That particular New York seemed galaxies away from the one I wanted to inhabit. I wanted Sophie to tell me I’d soon get to put that all behind me and move on to more glorified and satisfying assignments. And, more importantly, success with my own creative writing.

“Well, I am seeing something,” she said. “I’m seeing bookshelves . . .”

Oh, my god, bookshelves. I cut her off. “Do you think that means it’s time for me to write my book?”

A three-year gap between a prediction and its coming to fruition was relatively short in Sophie-time. As she explained, “What I see here could happen in ten minutes, or ten years from now.” Ten minutes or ten years? Couldn’t she pinpoint the timing of her predictions just a little more accurately? “But time isn’t linear, dear.” Whatever that meant.

I was referring to Adventures in Divorce, the memoir I’d been planning to write on the cheerful topic of my family’s legacy of failed marriages, including my own at 26. (Even my stepparents had stepparents.) If Sophie didn’t envision the book being published soon and to critical acclaim, I didn’t want to put myself through the slow torture of sitting quietly at my desk after my day job, enduring loneliness and boredom, recalling painful and embarrassing experiences, and wrestling unwieldy sentences into submission. I wasn’t going to take any chances if the time wasn’t right and if I didn’t already know it was going to be well received.

“Well, let’s ask the cards,” Sophie said. “Pick seven . . .”

And the answer was . . .

“The cards are saying that any time from now on is a good time.” That certainly narrowed things down.

Of course, it was the right answer. It’s always the right time to get started writing. Duh. And it’s always difficult, and there will never be any guarantees. And it’s a process, a slow one. Blah, blah, blah. I’d resisted that wisdom when it was imparted by instructors at the two MFA programs I’d dabbled in before quitting, plus every self-help book on writing I’d ever read, and I was less than thrilled when the distilled essence of it was delivered again by a high-priced psychic.

***

If I wasn’t producing much writing, it wasn’t for lack of space. My East 13th Street apartment had an extra little room for me to write in, and I did, some—mostly freelance articles and essays and a lame proposal for Adventures in Divorce. But I never pushed far enough through the difficulty of writing any one piece of the book for it to really go anywhere.

I had any number of ways to distract myself from that difficulty. There were countless hours of mental gymnastics trying to figure out one intermittently interested guy after another. There were longer and longer runs around the East River Park. There was singing, at the top of my lungs, in my apartment (my upstairs neighbor once popped down to ask, “Can we move the Joni Mitchell hour to a time when I’m not home?”) and at the weekly jazz open mics at Cleopatra’s Needle on the Upper West Side, and Rue B in my neighborhood. I took to the task of organizing casual dinners among the group of friends I considered my East Village family as if I were a professional event planner.

I had a place I could afford to write and live in alone in New York City, and I was squandering my time there. I tried not to think about that, and so I stopped noticing. But the years ticked by, quite linearly I might add, and somehow one day I was 28, and the next I was 38. I assumed I’d have that rent-stabilized apartment forever, which at 28 seemed like a great thing for a struggling writer. But at 38, still lonely and with few details of my life changed, I started to imagine that I’d grow old and die alone in that run-down shoebox, and it scared me.

***

Let me cut to the chase here. Ten years almost to the day after my first reading from Sophie, in the fall of 2003, I met a (goateed) guy named Brian.

Brian. Whose named starts with B.

An hour after our first date, brunch at Life Café, I attended a wedding reception—in a room with sharp angles and a buffet with really mediocre food. Well, the closest any room’s angles had come to being “sharp” in the decade since Sophie had predicted that detail. (The wedding was at the industrial-chic, poured-concrete-walled Tenth Street Lounge, where there were no soft edges. Whatever. Work with me.)

I had a place I could afford to write and live in alone in New York City, and I was squandering my time there. I tried not to think about that, and so I stopped noticing. But the years ticked by, quite linearly I might add, and somehow one day I was 28, and the next I was 38. I assumed I’d have that rent-stabilized apartment forever, which at 28 seemed like a great thing for a struggling writer. But at 38, still lonely and with few details of my life changed, I started to imagine that I’d grow old and die alone in that run-down shoebox, and it scared me.

Brian was a really nice guy, and fortunately, thanks to roughly $20,000 worth of psychotherapy, I no longer had a strong aversion to that. He was cute, smart, funny, creative, and, I would later learn, totally cool with me being a weird loner when I needed to be. He’d also soon come to encourage me to stop making my singing a secret affair, and accompany me on pretty much every instrument on recordings we’d make together.

But let’s get to the important stuff: he had real estate, specifically a rambling below-market-value loft in a Gothic Victorian former yeshiva on Avenue B, across from Tompkins Square Park. After our third date, he invited me up. As I stepped in behind him, I couldn’t believe my eyes—1,800 square feet on two levels, three bedrooms, high ceilings, exposed brick, big windows, an arched entryway, and other interesting architectural details. It was run-down with chipping paint, which gave it a bohemian feel similar to that in my apartment. Brian and I shared the same threadbare flea market style, with mismatched furniture, some of it picked up right off the curb—the same place I’d found my writing desk.

Only a few months after we started dating, I moved, unofficially, into that incredible, gaping loft, and began renting out my place on 13th Street—by the weekend, by the week, by the month via a company called New York Habitat, a precursor to Airbnb—as a way to keep it, just in case things with Brian didn’t work out. Eventually, though, toward the end of 2004, my super warned me that I was in danger of getting busted. “The landlord’s been asking me if you really live here,” he said. Brian and I had gotten engaged. There was no question we’d ultimately choose his 1,800 square feet over my 450. Maybe it was time to hand over my keys.

My last day in the apartment, after all my stuff had been moved out, I sat for a while on the scraped-up hardwood floor. I couldn’t decide whether, now that it was empty, the place looked like a spare art gallery or a seedy slum. New York City real estate is like that. How you perceive it is relative, mostly to time and to what other conditions you’ve lived in. The $600 dump I’d moved into with lumpy plaster walls, lopsided floors, and peeling paint hadn’t changed much over the years. Even with new windows, it was probably still a dump by many people’s standards. Although the next tenant would pay $2,150. Tenants, plural, that is. When I stopped by a few months later, the super told me there were four young women, NYU students, sharing the space. (Recently I saw it listed for $3,700.)

My last day in the apartment, after all my stuff had been moved out, I sat for a while on the scraped-up hardwood floor. It struck me that the sunlight streaming in was the same golden hue it had been when I moved in. I swear it could have been the same day. Had any of the things I remembered actually even happened here? The many lonely, gloomy days interspersed with relatively brighter ones? The all-nighters to meet freelance deadlines? Twelve birthdays? The parade of bad boyfriends, first nights together, tearful last nights, promises made and broken? Was this the moment before or the moment after? Maybe time isn’t linear.

Without my furniture, clothes, books, the memory-steeped markers of my time there, the place had a peacefulness to it that I wanted to inhabit for one moment longer. It struck me that the sunlight streaming in was the same golden hue it had been when I moved in. I swear it could have been the same day. Had any of the things I remembered actually even happened here? The many lonely, gloomy days interspersed with relatively brighter ones? The all-nighters to meet freelance deadlines? Twelve birthdays? The parade of bad boyfriends, first nights together, tearful last nights, promises made and broken? Was this the moment before or the moment after?

Maybe time isn’t linear.

***

Brian and I were officially cohabiting at his place on Tompkins Square Park for one measly month when we got the news: we were getting kicked out. The building had been awarded Landmark status, and we were allowed to stay just one more year, with our $1,350 rent nearly tripled. The week after we eloped, at thirty-nine and forty-two, we welcomed two roommates to help us afford the place. Yes—we got married and then we got roommates.

The building would undergo major renovations, and the rents would skyrocket to $6,500 and higher. Michel Gondry, followed by Matt Dillon, would each spend a couple of years living in our space.

First, though, we’d spend a bitter year in housing court trying to fight it. Toward the end of the expensive, infuriating legal process, when it became clear that we were probably going to lose the place, one of our lawyers asked each member of the tenants’ association, “Have you got some other place to go?”

And that’s when I heard it—Sophie’s voice. “Don’t give up the apartment.”

Shit! I gave up the apartment! How could I have given up the apartment?! I was suddenly sure those words Sophie had uttered so many years before pertained specifically to our current situation. I couldn’t believe it. I began to kick myself.

But also at some point during that struggle, Brian and I both found ourselves feeling soured on the East Village and the city as a whole. Never mind that we were getting priced out. The city wasn’t the same anymore. Of course, New York is never the same, from one day to the next. But now it seemed there was a more extreme, rapid level of gentrification. Every neighborhood was starting to appear and feel the same. Each one lost its individual character as nearly every deli, pizza place, shoemaker, or thrift shop was replaced by a Chase or a Duane Reade or a Chipotle, or a pricey, twee mini-cupcake shop. One by one, our favorite restaurants and shops went out of business. A three-dollar umbrella was now five. The Second Avenue Deli was now on Third Avenue. All this made it mercifully easy to leave the island we were getting kicked off anyway.

We moved upstate to Rosendale, a depressed little river town that’s become an outpost of what I’ve labeled the Downtown Diaspora. Nearly all our friends there moved up from either Lower Manhattan or Brooklyn—not realizing at the time that now we were the gentrifiers, upstate.

***

The first few years upstate, we didn’t really miss the city. We’d take the Trailways down as needed. One summer weekend, when we stayed at a friend’s West Village apartment, we went to breakfast at La Bonbonniere, a long-standing greasy spoon on Eighth Avenue near Horatio Street. (I’m obsessed with patronizing old, authentic, non-corporately-owned establishments before they perish.)

Seated next to us was a heavily made-up woman in her 80s who wasted no time striking up a conversation with us. She seemed to be one of those New York lonely people who spend so much time by themselves that as soon as they come into contact with other humans, they start babbling, almost involuntarily. I’d once been terrified of becoming one of them.

The woman, a onetime musical theater actress, asked us where we were from, and we somehow wound up on the topic of the apartment I’d let go. “I still sometimes kick myself,” I said.

“Listen to me,” she insisted. “A rent-controlled apartment can be a life sentence! I’ve been in my place for over sixty years, and it has kept me from the other things in life.” She said she’d forgone year-long U.S. and European tours with shows for fear of losing her studio—now $150 a month—if she’d sublet it. The place wasn’t big enough for two, and anytime living with someone or getting married was on the table, she felt too shackled to her low rent to take a chance and move out. There had been two broken engagements. She was filled with regret. “You made the right choice,” she said. It turned out New York City fell short as a life partner.

The woman, a onetime musical theater actress, asked us where we were from, and we somehow wound up on the topic of the apartment I’d let go. “I still sometimes kick myself,” I said. “Listen to me,” she insisted. “A rent-controlled apartment can be a life sentence! I’ve been in my place for over sixty years, and it has kept me from the other things in life.”

For a while afterward, that encounter helped me make peace with having forgotten Sophie’s first words to me when I finally needed them. But now, twenty years after having left, I am back to kicking myself—sometimes. After nine years, Rosendale got very small on us and we moved a few miles north to slightly bigger, more urban Kingston, trading a town of 6,000 for a city of 24,000. But in Kingston’s nine square miles, there’s still just a tiny fraction of the restaurants, shops, movie theaters, and other establishments that were in even just my neighborhood within the East Village.

I love my life upstate. But I also miss New York. I yearn for it something awful, the way you’d yearn for a lost lover. So what if the Lower East Side is now littered with gleaming glass buildings? So what if the familiar is steadily replaced by the unfamiliar? So what else is new? I miss the crowds. I miss the variety—of everything. I miss having perfect knowledge of where to eat and the latest rerouting of the B, D, Q line. I keep a MetroCard in my wallet at all times to ward off the feeling of being “bridge-and-tunnel” again.

I miss my cute little apartment. I miss having a home base, a place to drop my bags or even just to pee. Most of all, I miss the serendipity of simply walking out of my building, wandering for hours, and seeing where I land.

Every now and then, even without an appointment of any kind, I’ll hop on the Trailways to Port Authority the way I’d once hopped on the Long Island Rail Road, and I’ll walk for hours. I don’t make any plans. I don’t call any friends. I want it to once again be just the city and me.

Appreciate your ongoing "Leaving New York" or finding a workaround to the high cost of being there. So relatable...what is quirky and cool at 28 wears thin by 40. In 1992, I finally gave up my $275 fifth floor walkup with tub in the kitchen when rents were already passing $1000 there and I looked around knowing it was not my destiny to remain there like the older Ukranian folks who lived out their last years in my building. I moved to Colorado.

I wonder if you are still in touch with Sophie--my landsman. I'm also from western NY. I'm still in NYC--now in Queens--but this piece reminded me of my own basement studio apartment on the Upper West Side. $230/month when I moved there in 1977. Bars on the windows, view of the buildings' garbage cans. I attracted Peeping Toms. One hot summer night I was sitting on my little sofa watching my little TV when I noticed a gap in my venetian blinds. Someone's hand had reached in through the open, barred window and was watching me. Then he spoke: "I've got a big one. Wanna see?" I grabbed my fire-engine red landline phone and dragged it into the bathroom, shut the door, and called the police. It took them thirty minutes to come and when they did, they found the guy passed out near the garbage cans. Ah, youth! Last I checked on StreetEasy, my little basement studio now costs $1700 a month. And they have put up a locked gate, so the neighborhood "characters" can no longer access the two below street level windows.