My dad is dying.

Very slowly, but also very fast.

I visit him once a month from New York City, where I work editing behind-the-scenes footage for horror films overnight and try to make it as a filmmaker by day.

On this visit in 2011 I am trying to hang a mirror. The blue metal nail punctures straight through the wall. For the third time I’ve missed the stud. There’s a small constellation of pinholes scarring the white wall. My knuckles tap as I listen, testing for something solid behind thin sheetrock.

“Careful, my lease says I can’t leave holes in the walls,” my dad says, as he lights a cigarette and starts a coughing fit that shakes his 98-pound 65-year-old frame. I’m not used to his thinness; if anything I’m more accustomed to his slightly puffy face from a long-term prednisone prescription.

“Your lease also says you can’t smoke,” I say.

Air fresheners are placed strategically all over the small apartment. Motion-triggered, they make small snake-like “psst-psst” sounds when I pass them.

The hissing catches me off guard, making me jump even after months of visiting. One freshener sits on top of the refrigerator above the toaster. When we make toast the spring of the toaster triggers the air freshener and a mist of “fresh apple-vanilla scent” sprays right over the bread. It’s disgusting and also embarrassing.

I pull a check out of my wallet made out to him. “That’s great, will get me through this month,” he says.

“Only problem is there is a whole new month that comes right after this one, and then another one after that,” I say, gently. He laughs.

My dad’s apartment is a small studio. There is a bed where he lies, and an old, worn-out couch on one side of the room. On the other, an untouched, fully set dining table, ready for four. The plates are coated in a thin layer of dust and each dish still has its price sticker on the bottom. The napkins are placed in round holders. My dad, it seems, is perpetually waiting for dinner guests who never arrive.

I pull a check out of my wallet made out to him. “That’s great, will get me through this month,” he says…“Only problem is there is a whole new month that comes right after this one, and then another one after that,” I say, gently. He laughs.

I open the door and windows to let in the Vermont mountain air. The curtains move as wind tunnels through the apartment, drowning out the click and mechanical exhale of Dad’s oxygen machine, which hides, like a monster, in the closet. A long clear tube runs from the machine to my dad’s face, getting tangled up in various objects as he shuffles around the apartment.

“Right here?” I hold the heavy framed mirror up against the wall for him to see.

“Yeah, that’s great,” he says.

This time the hammer drives the nail into the stud. I sink a second nail directly across, lift the mirror and hope the alignment is right.

“Okay, dad, look!”

His eyes are small and always blinking behind his thick glasses. His hair is so thin I can’t believe he once used a pick to tame its mass of curls. In his youth he was a ladies’ man. “A free spirit,” his latest ex-wife calls him. He has a bevy of ex-wives who show up to take care of him now, but he is unattached for the first time in his life. I come to help take care of him, too, about once a month. He’s living in Jeffersonville, the town adjacent to Stowe, a fancy tourist destination in Vermont. Jeffersonville is where the workers who serve Stowe’s tourists stay.

Dad’s body is breaking down from a condition the doctors call, “failure to thrive.” Since 18, when he was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, an autoimmune disorder in which the body attacks itself, he has been constantly in and out of hospitals.

“I must’a bought those doctors three or four luxury cars by now,” he says.

Dad’s mother repeated her biggest regret in life, over and over again: “I could have married Doctor Kelkainy, he wanted to marry me. A doctor! Instead I married Bud.” Poor Bud had turned out to be nothing more than a bum, passed out in the hallway where his young son had to step over his body to enter their apartment. My dad asks me to sort through a batch of photos tossed loosely in an old wooden trunk. We are taking a final inventory of his things, of his life.

In his youth he was a ladies’ man. “A free spirit,” his latest ex-wife calls him. He has a bevy of ex-wives who show up to take care of him now, but he is unattached for the first time in his life. I come to help take care of him, too, about once a month.

The trunk smells of forgotten things, hidden from light. It’s lined with threadbare cotton that falls apart when I touch it, leaving powder on my fingers, like moths’ wings. He doesn’t know if the people in these photos are actually our relatives or strangers. My grandmother had a habit of collecting other people’s memories at garage sales. She also hoarded piles of costume jewelry, animal print clothes, and wigs of all colors. She was the first drag queen in my life. She read The National Enquirer for the latest “medical breakthroughs” and conspiracy theories. She was a fabulist depressive, refusing to accept the smallness of her life.

She would pace and rant about all those who did her wrong, her small son by her side, the only man left in her life — aside from the husband passed out in the hall and the much older son, Chuck, who ran far, far away to Panama, to Boston, to a middle-class wife, but eventually circled back to the bottle and his place on the floor, passed out like his father, in her hall.

I pick up a photo taken in the early ‘50s. In it my grandmother and father, by her side, are visible in a mirror. She’s holding the camera at her waist. They stare at their own reflections, behind them in the empty apartment. It’s beautiful and haunted, like a photograph by Diane Arbus. Next, I pick up a portrait of a black terrier. Tippy Witcomb is written on the back. This is definitely not from our family. This dog is out of our class, by name alone. I pocket the photo.

My grandmother had a habit of collecting other people’s memories at garage sales. She also hoarded piles of costume jewelry, animal print clothes, and wigs of all colors. She was the first drag queen in my life.

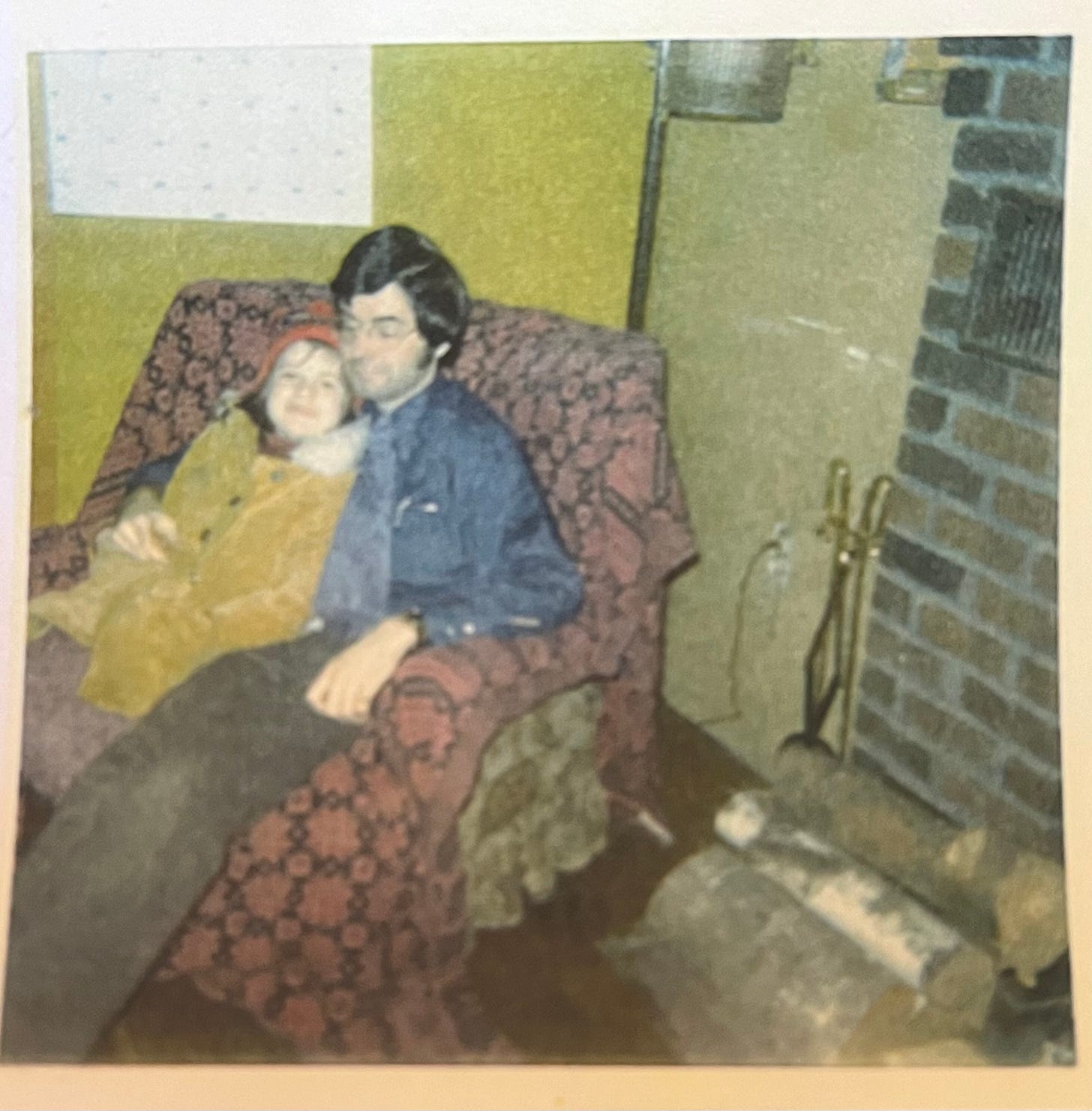

Dad and I look through a photo album his last ex-wife has dropped off. In it are pictures of him in his youth with captions she’s added over the images like “family matters” and “capture the action.”

We go through the album my mother dropped off. There are only a few pictures of me and Dad in it. My parents divorced when I was a baby, shortly after marrying and having me at 17. My mother left us, left me in the care of Dad. Her photos consist of shot after shot with no faces in the frame. Pictures of arms raising glasses in a toast; a bunch of balloons with the top of my head; an older man’s legs and slippered feet, arm extended, holding up a mug of beer.

She could never figure out where the viewfinder was on her camera so she just placed her eye against the body of the instamatic and took a shot. I like the photos a lot. They’re unintentionally unsentimental and artistic.

There is an inherent link of absence to a photo. A vining of capture and loss, catch and release. As a filmmaker, I obsess over the frame, stringing images together to reconstruct reality over and over again. The frame, what’s in the frame, but often most telling, what lies outside the frame. Perhaps the story lives in between the ones I tell.

Avant-garde screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière called filmmaking a form of subterfuge, in which reality and truth bends its will to the power of images; that film opens, “a new chapter in the age-old history of the lie.” Or as my uncle Chuck would say, “Telling someone a good story is a gift, it doesn’t matter if it’s true or not.”

***

Years of television had prepared me. My arms out, elbows straight, knees locked, both hands on the handle, finger on the trigger.

“Freeze!” I yelled as I pointed a gun directly at my dad.

My dad did freeze. He froze in a manner that was most literal. Every muscle in his body froze, his eyes widened. My toy gun became real at that moment.

Then he snapped out of it. When he did, he yelled. He shook and yelled, and pointed in that Dad-as-ruler-of-all-the-universe pointing way, toward my room. The plastic gun was confiscated. I was 9 and my father had just been taken hostage at a car dealership where he worked on that particular hot-concrete day of summer in a town appropriately named Rutland.

My father wakes up and retells the story. “Maybe I was a hero once,” he says.

CRACK. The glass bent and wobbled but did not break.

My dad flinched, catching the attention of his co-workers, who laughed.

The black bird fell limp to the grass below, its shiny chest moving up and down rapidly. My dad looked back and joined the laughter. “Jesus Christ.”

Three of the four walls at Nolan’s Chevrolet of Rutland were made of glass. The lot held 70 new cars spaced two feet apart in perfect rows. Dad stared at the hard blue sky, the dew-covered lawn, at the smudge on the once clean glass, and went to fetch the dead bird.

Back in his office, he moved a stack of manila folders with lists and plans for a business of his own. “A man needs to be his own boss, needs to be a man with a plan,” he said. He had a second wife, me, a child from his first marriage, and an old golden retriever. He was 26. Every night he vowed to quit this job.

Avant-garde screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière called filmmaking a form of subterfuge, in which reality and truth bends its will to the power of images; that film opens, “a new chapter in the age-old history of the lie.” Or as my uncle Chuck would say, “Telling someone a good story is a gift, it doesn’t matter if it’s true or not.”

The other salesmen entered the dealership as Dad sat behind his desk learning the specs for new car models. In order to sell you must believe in the need for the thing you’re selling. His brother, Chuck, despite being on welfare, bought a used Cadillac every couple of years. “As long as you have a car, you have a place to live,” Chuck told his little brother.

A new car smell is an intoxicating reek of promise, escape, power, mobility (upward or at very least horizontal), and status. Dad knows this as he convinces the prospective buyer to sit behind the wheel and close the door.

The dealership had its dramas. Matty, whose sales were down, had lost his confidence. He’d started to think that every new buyer was out to get him and it showed in his attitude. So after a few complaints, Ron, the owner, had fired him. Dad liked Matty, but there wasn’t anything he could do.

The day after, it was business as usual. Ron called to say he was stuck at the dentist; a second pot of coffee was brewing and the receptionist came in smiling at Dad. Their eye-contact was broken by a car burning rubber as it turned into the lot. The driver drove too fast and too close to the main showroom window, parking sideways. Dad’s muscles tightened. When Matty got out he looked rearranged. Like the thoughts he’d been thinking all night physically changed his face. Dad almost didn’t recognize him. The receptionist saw it too and smiled nervously as Matty walked in and demanded to see Ron.

“He’s out for the day, Matty,” Dad said.

“Well that’s too bad because I drove all the way here to shoot him,” Matty said.

Everyone stopped and turned slowly in a thickening wave of silence as they noticed the gun in Matty’s hand. It tapped against his leg, in a jumpy and loose way, like a hooked tout.

“He just let me go. You can’t just let someone go like that,” Matty said.

“I’m sure he’ll talk to you Matty, but he won’t be in all day,” Dad said, making sure to look him in the eyes.

“If I can’t shoot him then I’m just gonna have to shoot one of you, unless he comes down here.”

My dad once had a pyromaniac's desire for chaos, but also a knack for discovering grace in crisis. He was setting practice fires, maybe, or knew the way a forest needs to burn to grow.

Eight people stood in the showroom, spread out around a new beige car on display. Matty stood on one side of it with his gun out in front of him. A couple entered through the door. Click, click as it swung open then a whoosh, whoosh sound as Matty turned around. Could that be true, Dad thought. How could he hear the sound of Matty’s turn? But he remembered that sound distinctly.

The couple at the door smiled at the eight people, then looked at Matty, their faces contorting as they registered the gun and the possibility of danger. Whoosh, whoosh Dad heard again.

“GO!” Matty yelled at them, swinging the gun back to the 8 co-workers standing in a half circle around the beige car.

“I’ll let you go, one by one, until Ron shows up.” “But he’s not coming in, Matty,” Dad said.

“Then I’ll shoot the last person here.”

The Rutland police showed up, six cars parked adjacent to the showroom. The wide-brimmed sheriff’s hat visible behind Matty’s head and shoulders.

“Ok, Sue, you can go,” Matty said to the secretary. She looked at her co-workers, Dad and Gerry. Everyone else had already been released. They gestured for her to go.

Matty paced, looked at the police cars, then back at his co-workers. Dad told me that he still wanted to protect Matty, from himself, from the police. This scared dad more than the gun pointed at him, more than having been taken hostage.

Matty looked at my dad.

“Go,” Matty said to my dad, tilting his head toward the door. Dad looked at Gerry.

I wonder what I would do. I know what I’m supposed to do, but in reality I have no idea what I’m capable of.

Dad walked around the car. He said everything slowed down for him. Time is elastic. It is always this way. As he passed Matty however, he pretended to stumble. Was it pretend? Was it real? Either way he fell. Matty reacted on instinct and reached to help my dad. Gerry moved forward and grabbed Matty’s arms while Dad pinned the gun against the bumper of the new car.

Gerry and Dad wrestled him up to the car hood, like actors in a cop show. They shout clichés, “drop it, now!” They were bad-acting their own lives. The crowd out front, including the police, watched.

Dad and Gerry wrestled Matty, who was holding the gun tightly. My dad couldn’t get Matty’s finger off the trigger. He said the thing that finally made Matty drop the gun was when he gently massaged Matty’s shoulders. Dad just rubbed Matty’s shoulders and repeated softly, “It’s over, it’s all over, let go.” They held each other; it was the closest Dad ever felt to a man.

Dad was a big hero in a small town that day. But Ron worried about letting the story out, didn’t want anyone to get a similar idea, and so he made the newspaper bury it.

“The only difference between a hero and a fool is the outcome,” my dad says, finishing the story, stubbing his cigarette out in the ashtray. He laughs, the way you do when nothing is funny.

The blue haze of smoke that has surrounded him my whole life, hangs between us. In the sunlight it is almost beautiful, this smoke that slowly shuts his system down. He looks into his green plastic cigarette holder. He obsessively checks his oxygen level with a clip that attaches to the end of his finger, reaches for another oxycodone, gingerly places the small white tablet on his tongue, coughs, and lights another cigarette.

“Yeah I felt bad that day after Matty held us up, that I yelled at you like that. I felt really bad. I mean, you didn’t understand how a toy gun could be scary, can’t imagine having an actual gun pulled on you by someone you know. I liked the guy, we joked around together.” All I remember was his fear that day and that I seemed to have caused it and for a brief moment I had a dangerous power.

My dad once had a pyromaniac's desire for chaos, but also a knack for discovering grace in crisis. He was setting practice fires, maybe, or knew the way a forest needs to burn to grow. My dad was a binge drinker and binge leaver. Leaving my step mom and me fending for ourselves at times. When he was of a sober mindset he took care of me, was my protector, fed me elaborate meals, even though we had little to no money. When he was using or drinking, our life was chaotic and at times violent.

When he was of a sober mindset he took care of me, was my protector, fed me elaborate meals, even though we had little to no money. When he was using or drinking, our life was chaotic and at times violent…The story went like this. “You saved my life.” “No, you saved my life.” We said these words to each other. We were to blame, we were the heroes, we were the cause.

The story went like this. “You saved my life.” “No, you saved my life.” We said these words to each other. We were to blame, we were the heroes, we were the cause.

The sky and clouds bloom magenta; the mirror is a perfect square of pink on the white wall. I set a plate of food by him and sit on the bed like a cat as we watch the news. Next month he’ll turn 62. The room freshener sprays as I set my coffee cup down on the dresser.

Everyday he worries about losing his lease on this apartment so I buy him more of the dreaded air fresheners along with packs of cigarettes.

I tilt the mirror one more time until it is level. “How about this?” I ask.

He can no longer lie on his right side, to face the bedroom window with the view he fought so hard for. “That’s perfect. I can see Camel’s Hump… and the clouds.”

I cross to his side of the bed and look up at the mirror. From there I can see the mountains perfectly reflected. He looks up.

“Look at that,” he says, “You made me a new window.”

"My dad, it seems, is perpetually waiting for dinner guests who never arrive." and "They were bad-acting their own lives." Gah! stunner.

A fantastic story, with a story in a story.