Skiing and Crying

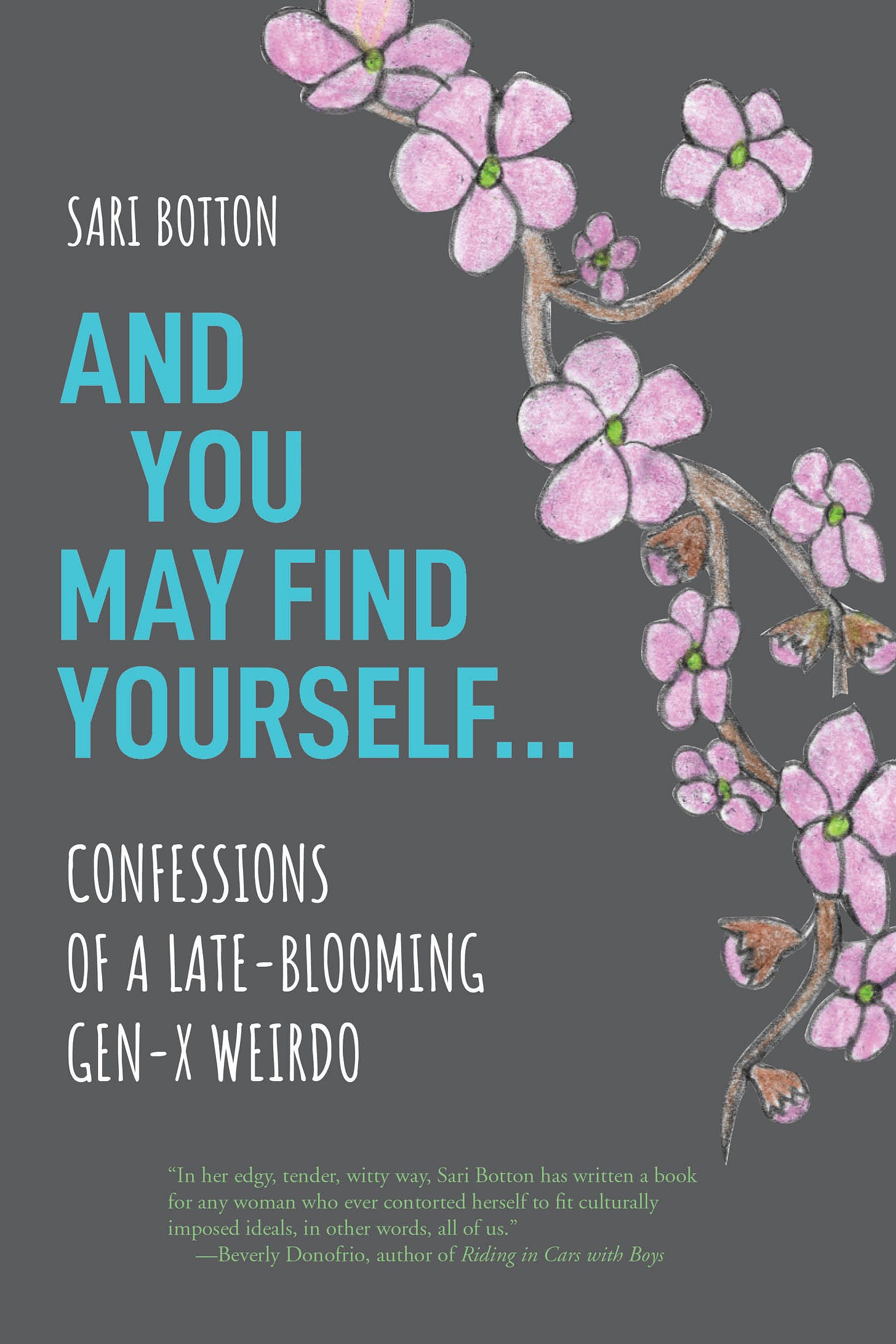

An excerpt from "And You May Find Yourself: Confessions of a Late-Blooming Gen-X Weirdo"

February, 1979.

Lucky me, I get to tag along with my new step-sister, a year older than me, for a day-trip on the slopes with her ski club. An eighth-grader, I’m thrilled to get to do something with high schoolers, and not just something, but an expensive sport that none of the kids in my blue collar hometown on Long Island engage in. But I’m scared of skiing, which I’ve never done before.

The year before, when my dad remarried into a family in Westchester, I became painfully class-conscious. Ashamed of my more humble beginnings, I grew obsessed with status labels, begging my mom to buy me Sasson jeans for the days I spent on Long Island (I eventually scored a horrible pair of green corduroy factory seconds from Denny’s Discount in Baldwin, with garish safety-yellow stitching), preppy chinos and wool sweaters for the days I spent in Westchester, and panties from Bloomingdale’s with their “bloomies” logo on the tush, so that I could convince the girls in the gym locker room that I’d suddenly, miraculously become rich.

I also took great pains to ditch any evidence of my Long Island accent, over-emphasizing “er” sounds I formerly pronounced more crudely as “uh”—for example, I now said “winter” instead of “wintuh”—but I also misguidedly added that sound where it didn’t belong, turning “tuna” fish into “tuner.”

The day of our ski trip to a mountain in northern New Jersey, I’m thrilled to have a chance to test-drive my new lockjaw on a bunch of older Westchester kids.

The next thing I know, I’m up in the sky on a chairlift, all by myself. The person operating the lift forgot to put down the bar meant to secure me in my seat, and I can’t reach it myself, making the whole gambit even more precarious.

But on the bus, I’m too shy to speak, even to the kids I met at my step-sister’s bat mitzvah the year before. I hear Dan Hill’s Sometimes When We Touch coming from someone’s hand-held transistor A.M. radio and I think I’m going to barf—god, that song is embarrassing—but then I notice a cute boy and pretty girl across the aisle holding hands in a very particular way, their fingers interlaced, and I decide that I want that, a boyfriend to interlace my fingers with. Maybe skiing has something to do with it.

Another thing I must have: a collection of beat-up chairlift tickets from prior trips hanging from my jacket zipper, like so many of the other kids have—a symbol of both privilege and a casual sportiness that eludes me, a klutz from a much humbler background.

Though I haven’t yet tried it, it’s difficult for me to imagine skiing frequently enough to accrue such a collection. I’m not even vaguely inclined toward sports, or anything that requires significant coordination—always among the last picked in gym, always tripping down the same short flight of stairs in my house. The closer we get to the mountain, the more nervous I become. I figure at least the teachers leading the trip will help me.

When we get to the mountain, though, the teachers tell us we’re on our own. “Go have fun!” I have absolutely no idea where to begin. I follow the other kids who don’t have their own skis to the area where you rent them. Then I follow some of them to a hill where an instructor is talking about how to “snow plow,” verb, by turning the points of your skis inward, forming the shape of a slice of pizza.

The next thing I know, I’m up in the sky on a chairlift, all by myself. The person operating the lift forgot to put down the bar meant to secure me in my seat, and I can’t reach it myself, making the whole gambit even more precarious.

Up in the air, I watch people quickly gliding off the lift when they get to the top, and realize I have no idea how to do that. The lift pauses for a minute, and I’m just hanging there, swinging slightly with the rhythm of all the other chairs bobbing from a cord in the sky. My heart pounds in my ears. How will I get off this thing? How will I do it quickly enough that the next person behind me doesn’t trample me?

I try looking down, and am glad to see I’m not too, too far from the ground—not as far as I’d been just a few minutes before. We’re only a short distance from the mound of snow you’re supposed to disembark on. One minute I’m looking down and imagining what it would feel like if I fell. The next, I am in fact tumbling from the lift. I crash land, hard, crying on impact. Suddenly there are all these grownups running toward me, and I’m mortified.

“Are you okay?”

“Don’t move! Stay still.”

“We need to make sure you haven’t broken anything, and don’t have a concussion.” They take me to small makeshift infirmary.

Miraculously, I am unscathed, although a little achy. The only thing broken is the binding on one of my rented skis. I’m worried I’ll have to pay for it, but the resort lets it slide.

One minute I’m looking down and imagining what it would feel like if I fell. The next, I am in fact tumbling from the lift. I crash land, hard, crying on impact. Suddenly there are all these grownups running toward me, and I’m mortified.

I spend the rest of the day drinking cocoa in the lodge by myself, counting the minutes until we can return home. On the bus, everyone asks if I’m alright, and I’m so embarrassed. One girl says, “Next time, you should sign up for lessons before getting on a lift!”

I’m not so sure there’ll be a next time.

Winter, 1992.

My first husband, Elliott, loves to ski. Each winter, from the time we meet in 1984, he prays I will miraculously fall in love with skiing, too, and stop being so bad at it, while simultaneously I pray he’ll forget the sport exists altogether.

I’m not at all direct about my lack of interest, for the same reason I’m not vocal about most things I’d prefer not to do: I believe I’m supposed to feel differently. As a general rule, any time I have an instinct that runs counter to most other people’s instincts, I instantly try to override it. I want to be perceived as Up for anything! Low-maintenance! And like the kind of effortlessly sporty person who always has several old, beat-up chairlift tickets casually hanging from her zipper.

So, a couple of times each year I find myself reluctantly stuffing weekend duffels with mismatched, borrowed ski garb, hauling those bags from the apartment to the car, and a few hours later, from the car to a hotel room in some snowy town north of our Long Island home. This time it’s South Fallsburg, in the southern Catskills.

I’m particularly resistant to this trip after another chairlift calamity the year before, when we’d gone to Stowe mountain in Vermont with a bunch of friends. There, I accidentally stayed on the chairlift after the rest of my beginner class (mostly grade-school children) knew to get off at “the midway point.” Still clueless as to how to disembark, I found myself having to basically summersault off the chairlift at the top of a black diamond, with the person who’d occupied the chair behind me tripping over me.

Our instructor saw that I’d accidentally stayed on the lift and stayed on, too. He found me at the summit, then had me hold onto his shoulders as he walked backwards down the mountain. I nearly died from the annoyed and pitying looks people shot at me.

I’d privately sworn off skiing that time. But I lost the nerve to stick to my guns when winter rolled around again, and Elliott started planning this trip to the Catskills. So, there I was again, in a state of utter dread, yet afraid to admit it.

The minute I arrive, Friday evening, I resort to Creative Visualization, envisioning lousy weather. Somehow it works; buckets of dense mountain rain come pouring down after dinner. I flick on the weather channel to make sure I’m not hallucinating. Sure enough, the local forecaster is nearly as surprised as I am. I could very well be off the hook.

My first husband, Elliott, loves to ski. Each winter, from the time we meet in 1984, he prays I will miraculously fall in love with skiing, too, and stop being so bad at it, while simultaneously I pray he’ll forget the sport exists altogether.

“I’m so sorry, Elliott,” I say, although I’m only slightly remorseful about having psychically willed away his weekend pleasure. “Maybe we’ll go skiing out West for a whole week next winter,” I offer cheerfully.

Yes, and maybe we’ll go to Pluto the winter after that.

But my luck, Saturday morning it’s sunny—and cold. There’s no avoiding it. Ski Ordeal ’92 is here.

At breakfast, I hear a woman who looks like an avid skier telling a friend she wouldn’t dare ski on a cold morning like this one, after a night of hard rain. I tuck this information away in my Last Resorts file as my stomach nervously kicks up a forkful of instant oatmeal.

We shuttle to the mountain and begin the whole annoying business of getting set up: filling out a rental form that looks like a tax return and asks nervy weight and height questions; waiting on one long line after another, for boots, then skis, then poles; figuring out how to carry the skis and poles the cool way and how to click the boots into the bindings without falling over every time. Inside, I’m wondering why this process alone doesn’t scare more people away; outside, I am the smiling, willing ski partner Elliott is wishing for.

“Sit now!” Elliott shouts as the chairlift scoops us up. Before we got on, Elliott asked the man in the booth to warn the guy at the landing to stop the lift when our chair arrived, so he could guide me as we disembarked. I cringe at the thought of what chairlift man #1 has probably radioed to chairlift man #2: “Let the nervous wreck and her overprotective husband off easy.” But I’m touched that Elliott wants to make this easier for me, and so I want to find it in my heart to stay positive, just for him.

My attitude adjustment has a short slope-life, though. I’m weaving my way down the novice trail in wide, unsteady S’s when I spot the first huge ice patch. Seeing no way around it, I stop short, shifting my weight up the mountain and freeze in place. What if it’s icy all the way down? I suddenly forget how to move, let alone ski.

“What happened?” Elliott calls up the slope, his tone caught somewhere between concern and disappointment. I wait a few minutes to speak, because I’m trying not to cry. But as soon as I open my mouth to explain, the waterworks start. I don’t want to be afraid. I want to be a good sport. I want to tell people I like skiing instead of becoming a grouch at the mere mention of the word. After all, skiing is great fun! Everybody knows that! Why, after seven winters and even more ski outings with Elliott, have I never been able to truly convince myself of that? Or learn to ski? Today, the ice patches aren’t helping.

I’m not at all direct about my lack of interest, for the same reason I’m not vocal about most things I’d prefer not to do: I believe I’m supposed to feel differently. As a general rule, any time I have an instinct that runs counter to most other people’s instincts, I instantly try to override it. I want to be perceived as Up for anything! Low-maintenance!

I pull myself together and Elliott talks me through a slow procession down the rest of the relatively shallow incline, and it’s not as bad as I thought. At the bottom, I consider calling it a day, but we’ve only been there twenty-five minutes, which means the $36 lift ticket and rental fee breaks down to more than $1 per minute. For some reason I decide that leaving will not be justified until I get the rate down to at least $.50.

So, up we go again, and again and again. I tense up at the same points, where the frozen ground glistens. At the end of each ten-minute run, Elliott praises my improvement and beams with pride while I try to calculate the current cost-per-minute ratio. How much longer before I can quit without encountering that sinking, giving-up feeling?

Just when I’ve gotten comfortable with the novice slope, Elliott suggests we advance to the next level. I can’t speak again—I’m fighting back more tears. I’m scared, I can’t feel my toes, but above all, I don’t know how much longer I can fake enthusiasm, especially on a more challenging slope. (I don’t yet know this is a metaphor for where I’m at more generally in our marriage.)

I don’t want to let Elliott down. But do I have to like everything he likes? I begin to realize that’s not always possible. Apparently, so does Elliott.

“How about you go into the lodge and get warmed up while I ski that other trail and you watch me through the window?” he proposes.

It sounds too easy. But something tells me Plan B would make Elliott happier than dragging his reluctant wife down a more difficult trail.

“Alright, go ahead, twist my arm.”

I settle into a booth with a full view of the mountain’s most difficult slope and carefully sip the cup of hot chocolate I’ve hardly earned. Each time I see the fluffy red down jacket and the big smile approach the bottom, I can’t help but smile too. I cheer out loud for Elliott and forget about ice patches and frozen toes and chairlifts, and even spring and summer.

It turns out to be our last ski trip together. Our last winter. Our last everything. I’m a couple of months shy of 27 when I move out. As I do, I swear off skiing forever.

Winter, 2002.

You know, “forever” is an awfully long time.

Did I ski again? Reader, I skied again—as usual, for the express purpose of trying to keep a man pleased with me. (I do not recommend this approach to relationship sustainment. Do not try this at home. Or at a ski resort.)

That’s right, nine years after the end of my marriage, at 36 years of age, I am back on my bullshit, doing a thing I’m quite certain I hate to please someone I like—in this case Zach, a younger man, by six years.

When I tell the story of Zach and me, I refer to him as “my 9/11 boyfriend,” someone I met in the throes of post-terror-attack anxiety and loneliness at a vigil in Union Square a few days after the towers came down, and my shrink suggested I open up to meeting someone new.

My younger boyfriend Zach works six days a week, and on the seventh, just like god, he rests. And by “rests,” I mean he goes skiing at Hunter Mountain. When he invites me to join him, I do not state, accurately, “No thank you. I do not like to ski.”

Zach is too young for me, not so much chronologically as emotionally. Even at 30, he is in many ways still a boy, living half the year traveling in a van with his dog. (The good half of the year in the northeast—the warm one.) In a key way, though, Zach is a better choice than prior boyfriends: he is sweet and kind. I am being treated by an ace psychotherapist who is helping me overcome my long-standing allergy to nice men, and so in that way, choosing Zach is a sign of progress.

Zach works six days a week, and on the seventh, just like god, he rests. And by “rests,” I mean he goes skiing at Hunter Mountain. This means skiing, a thing I undoubtedly hate, is now a weekly affair for me. I do not suggest to Zach any alternative activities that I might enjoy. (Although I do once bring him to a Richard Foreman play at the St. Marks Church, which utterly baffles him.) When he invites me to Hunter with him, I do not state, accurately, “No thank you. I do not like to ski.”

No matter how many times I go skiing with Zach, no matter how many runs down the bunny hill he takes alongside me, coaching me, shouting “Make wide S’s and you won’t fall!” I do not get any better at it. I miserably spend every Tuesday at Hunter, mostly killing time in the mountain’s beginner school with a bunch of 10-year-olds while Zach cruises down black diamonds. This goes on for the greater part of two winters, until the inevitable comes to pass, and Zach finds someone younger and no doubt sportier than me.

October, 2003 to the present.

The following fall, I meet my husband, Brian. Soon after that, I “graduate” from my four-year course of pschotherapy with the crackerjack shrink, who’s been encouraging me to unlearn pretending to be who I’m not.

On an early date, Brian tells me the story of his most recent ski trip in Vermont, during which a close friend, an expert skier, collided with a tree, breaking his neck and a few limbs. The jagged edge of one of his shattered tibias was protruding from his flesh inside his boot, which needed to be removed with a saw.

“Yeah, stories like that are part of why I don’t ski,” I reply. “Also, I just don’t like it.”

We’ve been married 18 years now. Brian has skied a few times since we got together, although, fortunately for both of us, it’s not really his thing. I have never once skied with him. I’m quite certain I never will.

I loved your story and relate. When I was in my 20s, I married a mountain man from Seattle who literally did ballet while skiing downhill. I skiied and fell alone, with the 10 year olds.

When I was 30, we divorced and I took a ski course in VT for women, which gave me confidence and technique. And I joined several friends for week-long ski trips to Colorado. My second husband looked like a fearless gorilla on skis, and tricked me into taking a lift up a black diamond slope. I slid on my ass all the way down. No matter how much experience and improvement I gained, I dreafed every ski trip. Shortly after my son was born, I had the guts to quit skiing. The relief was magnificent! I am now 73 years old and haven't skied in years. I'd rather read and write, while bundled up in my warm apartment.

I've lived in Colorado my entire life and I hate skiing. I hate the lift, the wind, falling, getting cold, paying a lot of money, getting up early on days when I should sleep in, all of it!!!! Thank you!