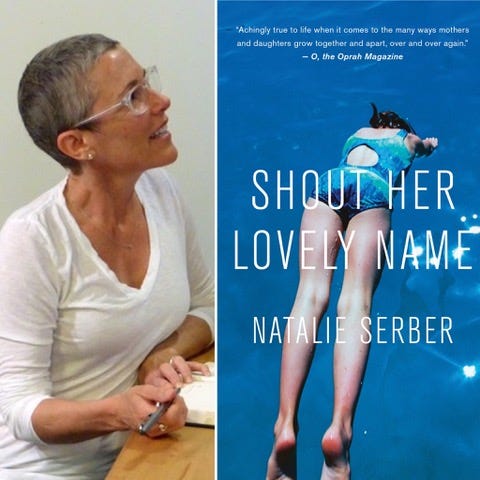

Tell Me, What Do You Think About You?

Natalie Serber surprises herself by repeating some of her mother’s regrettable choices.

CW: Suicide.

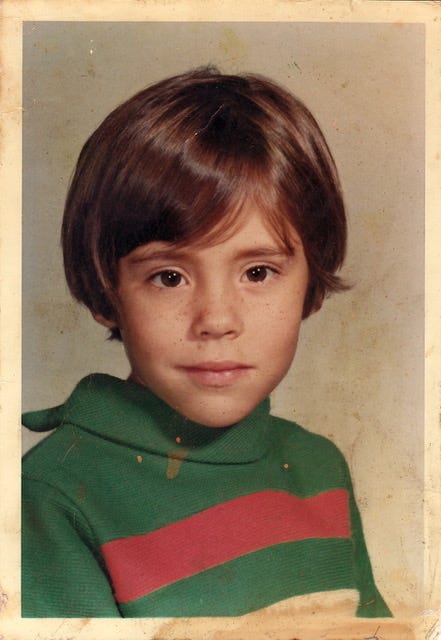

Girls at my new school dangled rabbit feet from their belt loops for good luck and wrote in five-year diaries that came with slim gold keys. Because my mother could afford neither, I made my own luck and diary by decorating the cover of a blue spiral notebook with cartoon rabbits and the words Dear Diary written in bubble letters. Within I confided about dogs on my block in the Hollywood Foothills, a cute boy, and the girls with whom I hoped to become friends. In the brief time I kept it, Dear Diary was my sole confidant. Careless or naïve, I left DD lying around our apartment, in the kitchen, in the bathroom, a pencil stub tucked between the pages.

In February I’d written about a boy in my second-grade class with wavy brown hair spilling down his forehead upon whom I crushed. I think his name was Robert. Sifting through my package of drugstore Valentines, I chose for him one with roses and hearts, suggesting true love.

Robert, a haystack of cards on his desk, slit open my red-enveloped Valentine, and then here he came, striding toward me. I twined my feet around the metal legs of my desk, looked to see if any girls noticed because it was the girls noticing him noticing me that truly mattered. When he reached me, he audibly farted and kept walking.

I wrote in DD about my disappointment. Robert’s act was embarrassing and gross. Kids giggled. But it was manageable.

In the brief time I kept it, Dear Diary was my sole confidant. Careless or naïve, I left DD lying around our apartment, in the kitchen, in the bathroom, a pencil stub tucked between the pages.

A few days later my mother and her friends kicked off their shoes in our living room. Smoke coiled from lipsticked cigarettes, a cloudy haze lingered over the couch where they listened to Nancy Wilson and sipped jug wine from jelly glasses. They flicked ashes into empty tuna cans, crossed their stockinged legs with a swish-swish, and patted the couch for me to skootch between them. Did I like my teacher? What was my favorite subject? Any special boys? They stroked my hair and pulled me in for a “little sugar.” I’m sure I settled in, talking and talking.

Across the room my mother gently tugged at her eyelids, removing the spider legs of her false eyelashes and sticking them to her jelly glass. “Enough already.” She held out the glass for me to deliver to the bathroom.

When I drew close she made a loud fart sound and her friends laughed—not jeering, but now I knew she’d shared DD with them. It’s easy to recall the feeling—an umbrella opening in my throat, blocking my breath. Wavy haired Robert hadn’t liked me back, which was disappointing but survivable. In front of her friends, my mother made it a joke—I wasn’t good enough for the boy. The moment could have gone different ways. I could have been brought into the fold. The women telling me, Oh honey, men will disappoint you. But they did not. In our living room I learned humiliation came with the territory of girlhood. My mother knew humiliation from a string of rejections by men, including my father. Perhaps she thought humiliation was something I should expect. I rushed from the room, embarrassed by what I’d written, ashamed I’d given the Valentine. I crumpled DD.

I wish I could say my mother’s intention had been gentle teasing. But she did not gently tease. “Lighten up!” she may have called after me. Often she wondered how she’d ended up with me, an intense kid. “Lighten up,” was her admonition, not that I should shine brightly, but that I shouldn’t express my “outsized-drama.”

Ten years ago I was walking on Nye Beach on the Oregon Coast. I’d been invited to give a reading at the art center. I’d turned 50, had my first book published, my daughter—my youngest child—had gone off to college, and I’d been diagnosed with cancer. It was staggering and I’d written about it in a journal, a grown-up version of DD, that I was happy to share, and that became my second book. The cancer I had was small—someone called it “baby-cancer,” which felt unkind to me and unkind to babies. A radiologist told me to pull up my “big girl pants” and get radiation already. But the cancer I had was an aggressive baby and big girl pants weren’t going to be enough, so, along with the bi-lateral mastectomy, I’d needed chemotherapy. That was a blow yet here I was, on this beautiful beach in the sunshine, growing new soft hair, preparing to read from my book.

It’s easy to recall the feeling—an umbrella opening in my throat, blocking my breath. Wavy haired Robert hadn’t liked me back, which was disappointing but survivable. In front of her friends, my mother made it a joke—I wasn’t good enough for the boy.

I was miserable, withdrawn into darkness. My frightened husband insisted he accompany me to the coast. He drove and for that I am grateful because I think, and I don’t say this for outsized- drama, had he not, I may have driven myself at high speed into a tree. I’d been thinking a lot about it and hadn’t shared my plan with anyone.

The hormone suppressing medication, meant to keep the cancer from returning, brought menopause in a thunderclap, along with a full body rash. If you lightly scratched my skin, if my glasses sat too long on the bridge of my nose, if my waistband or my socks were snug, an angry red line appeared and would remain for hours, sometimes days. I had new scars, missing parts, fake parts, hot flashes, inexplicable numbing and pain. I felt as if I’d been dismembered by dogs and strewn about. I didn’t see a way through.

The winter had been particularly stormy, leaving the beach piled high with tangled roots, entire tree trunks which had been blown down, swept into rivers and creeks, washed out to sea, only to return to shore here. Stumbling over driftwood, bits of frayed rope and ravaged plastic water bottles—so many water bottles—I held my cellphone to my ear, crying to my mother who listened from her couch, her TV on low, she heard my despair. She made sympathetic sounds. I cried harder. When anyone, particularly my mother, listens with tenderness, I cry harder. “Oh honey,” her tiny voice pleaded through my phone. She did not tell me to lighten up because desperation and hopelessness were also feelings she understood. In this moment, I was my mother’s daughter. “Hang on.”

I humiliated my daughter in our living room. Friends were over for drinks on an autumn afternoon. Light reflected off the yellow Gingko tree in our yard. We had Pinot Noir in our glasses, a tray of Manchego, baguette and green olives. Here came my bright girl, perhaps 16 at the time, her eyes shining with excitement from her day. Sitting between our neighbor and me she began to tell us about it. I watched and listened as she kept talking. She shared something that delighted her. And then, I chided my exuberant girl, “Enough about you, what do you think about you?”

…the cancer I had was an aggressive baby and big girl pants weren’t going to be enough, so, along with the bi-lateral mastectomy, I’d needed chemotherapy. That was a blow yet here I was, on this beautiful beach in the sunshine, growing new soft hair, preparing to read from my book.

My daughter’s face stilled. I knew in the moment exactly what I’d done. I reached for her hand, which she drew away. I said, “I’m sorry. I was joking. Please, go on.” Perhaps I’d wanted the conversation to return to what it had been before she arrived, perhaps I grew bored. Why wasn’t her glee enough to sustain my attention? Maybe she took too much light. I shudder to think I was that petty. The shame I felt then, and now feel, is an inside job, so much larger than the shame I felt when my mother made the fart sound in our living room. I wish I could lay the blame at my mother’s feet. I wish I could lay the blame at the feet of a world that pits women against women. Were it today, I would fiercely defend my daughter’s right to keep the mic for as long as she wished. But on that day I did not. I made it hard for her to feel free. The blame lands at my feet.

When I recently told a friend this story, the first time I’d told it to anyone, she said, “Maybe you were trying to teach her how to have a conversation? To stop and listen.”

God, do I love my friend for saying that. But I wasn’t teaching my daughter anything except that women shouldn’t hog the light. Did I think humiliation was something she should expect? Something women deserved?

When I was 5 I woke to find my mother on the ugly tweed couch that came with our apartment. Her legs curled beneath her, she wore baby-doll pajamas with puffy sleeves, and her forehead rested in her hand. A full ashtray and an empty jelly glass made a still life on the coffee table, along with a small brown prescription bottle, the white lid popped off. The way I remember the moment, a record was spinning on the stereo, the needle thumping against the label. The room was too warm and too dark, the drapes still drawn. On the couch beside my mother the envelope of my school pictures—wallet sized, five by seven, eight by ten—had been slit open. Two dozen heads scattered around her. My short hair shining, eyes solemn, cheeks freckled, I wore the green dress my mother selected for me, though I disliked it so much .

Here came my bright girl, perhaps 16 at the time, her eyes shining with excitement from her day. Sitting between our neighbor and me she began to tell us about it. I watched and listened as she kept talking. She shared something that delighted her. And then, I chided my exuberant girl, “Enough about you, what do you think about you?”

She patted a cushion. "Skootch up." I crossed my arms over my body and remained standing. She’d been awake all night. She was so sad. She wanted to end it, to kill herself. I didn’t know what to do with that information. "You saved me, Sunshine." She reached for my elbow with her dry, light hand. "I hung on to your picture all night. You are my best thing. You are a good girl."

Good girl was now my job. I made my own cinnamon toast, kept things neat in my desk at school, made my bed, woke up happy, kept watch. My mother kept Daily Living Hygiene Lists: Get up. Get dressed. Brush teeth. Take Natalie to school. Go to work. Pick up Natalie. Order chicken delight.

When my children turned 4 then 5 then 6, I safeguarded their childhood. Mermaid birthday cakes, bath time tantrums, bedtime stories, footie pajamas—all of it happened. As a young mother I felt outraged for my kid-self, for what I’d missed out on.

After dinner one evening, my mother and I may have been watching my children chase the dog in our backyard, maybe I was washing the dishes while she finished her wine. I surprised myself by asking, "How could you have done that to a little girl? To me?"

"What about me?" she’d said, affronted and indignant, her jaw muscles clenching. "I was single and alone. Heartbroken. I was only 27. Do you know how I felt?"

"I was 5."

There would be no gesture. No reaching across the table. No, That must have been really hard. Not from her. Not from me.

Walking along a different beach, my friend told me of her huge achievement. She’d received an academic award with a hefty grant. She’d worked terribly hard and had every right to be proud, to share the details of her success, and I was proud with her. Pelicans rose and crashed into the Pacific beside us, causing joyful eruptions of salt spray. But my friend had incredulity tucked into her cheek. When she’d sung of her achievement to her family, her teenaged daughter said through gnashed teeth, “It’s my time to shine.”

We laughed, my friend and me. “It’s my time to shine,” became a punchline, purportedly making fun of moments when we felt dimmed, over-shadowed. The phrase brought us closer the way an inside joke does. “It’s my time to shine!” we crowed when someone got a new job or a good haircut, or soft boiled a perfect egg—anything at all.

But there was a crushing seed of despair in her girl’s exclamation. I think the reason I laughed at her daughter’s fierce and tender declaration was because at her age, 17, I would not have been brave enough to say those words aloud. I grew up believing other women’s success diminished mine. I had been trained to hide in the psychic bathroom and whisper in my mind, “Stop making me look bad. There’s not enough light to go around.” I was embarrassed by my collusion with the idea of scarcity. Her girl was brave enough to say it out loud.

I grew up believing other women’s success diminished mine. I had been trained to hide in the psychic bathroom and whisper in my mind, “Stop making me look bad. There’s not enough light to go around.” I was embarrassed by my collusion with the idea of scarcity.

It didn’t occur to me that female competition was a construct, that success isn't finite. Humiliation and despair needn’t be dominant emotions of womanhood, as they had been for my mother. When our friends, sisters, mothers, daughters brightly shine, they light us up, too. That is shine theory. Stand beside the bright light. We should all be telling each other to lighten up.

Please, I wish I’d said to my daughter, tell me everything about your day. Please, I wish I’d said to my mother, tell me about the ways men can disappoint. Please, I wish I’d said for myself, I was too small to carry your burden, but now, I wish you would tell me more. And, thank you for holding on.

Again I’m walking on Nye Beach. It was ten years ago that I wanted to drive my car into a tree. When I walked here before, having just finished chemotherapy, on the awful cocktail of medication, I was so deeply at a loss for how to be in my changed body. I recognized myself only in numb and painful pieces. Today the beach is clear of wood and plastic, and it’s a joy to move my legs on the hard sand. Sea grass, kelp, shells, and jellyfish stud the beach. What I make of the detritus: hair from seagrass, lungs made of hinged shells, a seaweed Fallopian tube, a kelp heart. The seawash returns me to my body.

I call my mother, still on her couch, Anderson Cooper in the background. “It happened,” she says. “I made it. I’m old. I regret nothing.” Maybe that’s the truth. “You’re old too,” she says, still wanting my company.

And then this, my daughter texts me with idle bits. Our dog humps all the puppies at the park! How do you make fondue? I like your haircut! What’s wrong? When I tell her nothing is wrong, she says, Why are you using periods? In your texts? The punctuation makes you sound angry! Periods insinuate anger! I am not angry! If proper grammar makes me sound mad, grammar be damned! In communication with my girl, I will punctuate with glee!

There are so many accumulated cuts, both by my hand, and on my body. Cuts that formed me, that formed my friends, my mother, my daughter. I gaze at the faint day moon, a fingernail in the light sky. I don’t know what to say about the moon up there. Memories of wrongs that can never completely be undone? It seems trite, to make the moon my therapist, my metaphor. Perhaps we just go forward, mindful, kind, messy, and forgiving. The shining moon is lit by the sun. “Tell me, what do you think about you?”

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 800-273-TALK (8255), 988 (call or text) or 988lifeline.org (chat).