The Accurate Term

Her 12-year-old son’s questions about consent forced Natalie Serber to reconsider a long-ago night.

CW: Rape

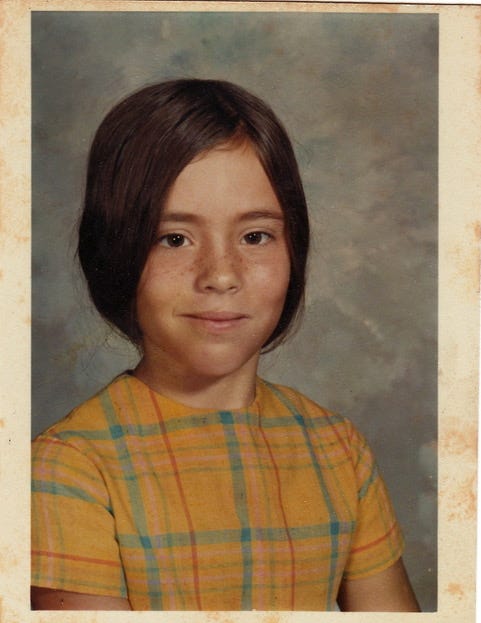

I was a scared kid—fearful of snakes, failing a spelling test, getting lost in a department store, waiting alone in the car while my mom dashed into 7-11 for milk and cigarettes. I was afraid of strangers, of being tied up, gagged, and bruised like the pretty girls I saw on TV. And though I didn’t understand what it meant; I was afraid of being raped.

My single mother worked two jobs to support us in the 1960s, and each required a different performance of feminism. As a cocktail waitress her skirt had to reveal. As a schoolteacher her skirt had to conceal. She once was made to kneel in the principal’s office; the skirt fabric hitting the floor was proof of her morality. At the jazz club, a hand permitted to linger on her thigh was proof she was fun and fuckable, worthy of a big tip. She, like a lot of women, suffered the whiplash of being too sexy and not sexy enough.

In her twenties she relied upon heels, hose, hairspray, and Helen Gurley Brown, who sanctified female sexuality and told her yes, she could have it all—a kid, two jobs, and a satisfying sex life. My mom also wanted love. On date nights she’d swan around our apartment in her little black dress, instructing the babysitter—one scoop of thin mint ice cream, bed by eight, and no, the babysitter could not invite her boyfriend over. She then would rub my head like her own good luck charm, and announce, “I’m going to get you a father.”

In her thirties my mother suffered a blistering break-up with a traveling gem salesman who told her he didn’t want an “instant family.” She stopped promising me a father and flounced out the door, not in a little black dress, but in bellbottoms and a sheer blouse, headed to a bar with girlfriends. She had diet pills, a diaphragm, and drugs. My mother burned her bra, experimented with LSD, sunbathed topless, was a groupie for a famous band. She was beautiful and carefree. And though she touted themes of freedom and sisterhood, she’d also internalized the dictum worst thing a woman could be was an old maid.

Sometimes my mother was giddy, dancing around the house to Mick Jagger. Sometimes depleted, nursing a hangover and depression in bed with the curtains drawn. In the morning she weighed herself and stood sideways before the mirror to check if her stomach pooched out. I learned from my mother that men were confusing at best, dangerous at worst, and a woman’s self-worth was tightly knit to male attention.

My mother may not have had love, but she had lots of men, lots of casual sex, lots of conversations with her girlfriends around the kitchen table with wine and cigarettes. I was privy to all of it. I listened from my perch on the counter, drawing on the white cardboard inserts from her panty-hose packages. The women laughed and lamented about all the good men being taken, about “lame-fucks,” about “being horny.”

At night I heard frightening moans in the bed across the room from mine or worse, crying when she was alone. Sometimes my mother was giddy, dancing around the house to Mick Jagger. Sometimes depleted, nursing a hangover and depression in bed with the curtains drawn. In the morning she weighed herself and stood sideways before the mirror to check if her stomach pooched out. I learned from my mother that men were confusing at best, dangerous at worst, and a woman’s self-worth was tightly knit to male attention.

Along with my fear of being separated from her in Macy’s, or stolen from her car at 7-11, the idea that male attention, and not me, made my mother happy, terrified me. For when she was unhappy, we were separated not by crowds, nor kidnappers, but by her darkness.

Weeknights my mother and I heated Swanson chicken potpies and put placemats on the coffee table to watch the news. Planes were hijacked. Women marched for abortion rights and for the ERA (same as now.) Patti Hearst was kidnapped and locked in a closet. A mass-murderer terrorized our beach town, raping and killing co-eds, burying them in the woods, making Santa Cruz the murder capital of the world. My mom poked at her food, graded her students’ homework, and after she’d had enough of planes, marching, and kidnapping, she’d flick her wrist toward the TV. “Get rid of this.”

I’d switch to The Partridge Family, a single mom with a band! Or I’d find The Brady Bunch, six kids and a maid! Or The Bob Newhart Show, a stable marriage and wacky, dateable neighbors! But the sitcoms didn’t erase what I was learning on the news and in our home, that to be a woman was to be traumatized, robbed of your body, and sad.

Once I was ten, my mom said I was old enough to stay home without a babysitter. My rape fears surged. Alone and shaky, I began dialing 911 and then hanging up, just to be certain someone was actually on the line. I obsessively checked the windows and the doors. I turned on all the lights and lengthened the cord of our yellow rotary phone until it reached beside me on the couch. I watched powerful, sexy women on TV. Charlie’s Angels, slim-thighed with perfect hair, always caught the bad guy. The Bionic Woman who in one episode was crowned a beauty queen, only to be kidnapped by nefarious men, and then escaped by lifting cars off the ground, all while dressed in a peach-colored ball gown. I had none of those things. Not the hair, not the slim thighs, not the bionic body parts. I identified with the tied-up woman, the girl with a gun to her head, the teenager stuffed in the trunk.

Eventually I’d fall asleep, and my mom, coming in late, maybe wobbly, maybe not alone, would turn off the TV and send me to my bed. I never told her I was afraid.

Once I was ten, my mom said I was old enough to stay home without a babysitter. My rape fears surged. Alone and shaky, I began dialing 911 and then hanging up, just to be certain someone was actually on the line. I obsessively checked the windows and the doors. I turned on all the lights and lengthened the cord of our yellow rotary phone until it reached beside me on the couch.

Then I was raped. At sixteen, striving to be popular, fun, a carefree party girl, I accepted a red Solo cup from a stranger at a party. And then I was in the backseat of a car, my pants around my ankles, with the older guy on top of me, his greasy mouse-brown hair flopping against my forehead. And then I was throwing up in the gutter. And then I was home, alone in my bed, curled toward the wall. I fell into a dreamless sleep. When I woke, my head felt hatcheted. My mattress was wet. I’d peed the bed, doubling my shame.

I told no one. And if I had, I wouldn’t have called it “rape,” because there was no rope, no gag, no gun to my head, no trunk of a car, and not one bruise on my body. I believed I had put myself beneath him. I’d been preening beside him. I accepted the red Solo cup. I had a hazy memory of the backseat, pressure, darkness broken by the streetlight in the rear window, the smell of dirty laundry, my ankles tangled in my yanked-down pants.

For years I’d witnessed my mother’s sex life. Did she enjoy or endure sex? I would try to piece things out the next morning, when whichever man had shared her bed, rumpled, whiskered, hungover, would lean at our kitchen counter in low-slung jeans with a thumb ring, drinking black coffee my mom served him. She might retie her bathrobe, sip her sweet, light coffee, anxious for him to leave, to stay, to ask if he could call her. After he left, she might joke about “last call” making everyone at the bar “fuckable,” and claim to be done with men, or she might sing in falsetto, “It’s him!” every time the phone rang. I decoded pleasure or disappointment in the way she struck her match and inhaled her cigarette. Monday morning she’d go to work, the weekend behind her, the next one ahead.

Was the keg party, the greasy hair, the backseat, the wet mattress, the hangover, and the humiliation the beginning of my cycle of weekends?

What happened to me was not an anomaly. Nor was it the fault of my upbringing. There are plenty of girls raised in different homes and plenty strangers with bad intentions. Growing up in my mother’s house may not have put me beneath a stranger against my will, but it did form my response to that night. I spent hours alone in my bedroom, over-plucking my eyebrows, meticulously splitting my already split ends. My hair was frayed and lifeless, my brows a narrow arch of perpetual surprise. “They look nice,” a friend of my mother’s commented. But there was a question mark at the end of her declaration. I returned to parties in the same backyard, drank beer from more red Solo cups.

I told no one. And if I had, I wouldn’t have called it “rape,” because there was no rope, no gag, no gun to my head, no trunk of a car, and not one bruise on my body. I believed I had put myself beneath him. I’d been preening beside him. I accepted the red Solo cup. I had a hazy memory of the backseat, pressure, darkness broken by the streetlight in the rear window, the smell of dirty laundry, my ankles tangled in my yanked-down pants.

I’d wanted to be a different kind of woman, like Ann Marie from That Girl, with her perfect eyebrows, protective father, and can-do attitude. Or Mary Richards who turned the world on with her smile, wore slacks to her glamourous job at a TV station and volunteered to work with needy kids. Or Mary’s friend, Rhoda Morgenstern, who wore bohemian scarves and hoop earrings, who couldn’t get a date, yet had a terrific job as a department store window dresser. These TV women, unlike my mother, and unlike the me I feared I was becoming, respected their body’s borders; they weren’t unhappy pretending to be happy.

In my view, I’d allowed some guy to fuck me, age 16, and then leave me in his car. I hadn’t said yes, but I hadn’t said no. I was the worst thing a girl could be in 1978, a slut, a label I secretly ascribed to my mother. The backseat sex was an assault on my body, and the shame was an assault on my identity. It was as if I had some psychological auto-immune disorder, me against me. The worst thing a girl can be is her own enemy.

Decades later we all learned about roofies, and I began to understand the story of that night differently. Was I roofied? I had been flattered to be handed a red Solo cup by an older guy who seemed to be into me. Perhaps that is where I was most like my mother: my self-worth was also informed by male attention.

I married, became a mother. My family and I went on beach vacations, we camped, had bagels on Saturday mornings, got a dog, then another. Training wheels came off bicycles, spelling tests went on the fridge, curfews got a little later. We ate together around a table. After dinner we popped in a Seinfeld DVD. Everyone loved Kramer. We laughed about puffy shirts, and bubble boys, and the “master-of-my-domain” contest. We talked about body autonomy; we talked about being ready for sex. My husband and I celebrated our fifteen-year anniversary. I was fine. Better than fine. If ever I thought about that stranger’s car, it was random, awake in the early morning dark, or waiting at a red light. “Maybe that was rape.”

Until my son, at twelve, called me into his room to watch a funny video. Frat-bros were doing a skit, a parody of something they didn’t believe in, date rape. One of the beefy boy/men cornered another pretending to be the girl. They went from fake kissing with hands over their mouths, to cajoling, to forcing. The “girl” was pressed face-first against a bunkbed, the dude whisper-yelling into her ear, sneering while she made high-pitched squeals of protest through small giggles and smiles. She played the worst kind of girl, the one who says no, but everyone knows she really wants it. The tease.

My son, already taller than me, watched the screen, watched me, then watched the screen again. Committed to neither laughter nor disgust, he seemed to be asking, was this funny? Was this harmless? What is true?

The “girl” flipped toward the bed, the boy trapped her beneath his full body weight. My breath snagged. My hand covered my mouth. My son’s bed was unmade, dirty clothes littered the floor around our ankles, and the room smelled of sweat and dirt and old crackers. I knew that smell.

“Turn it off,” I said. “Turn it off.”

His gaze snapped from the screen to me. Was he in trouble? What had he done wrong?

I clasped my hands together to hide their shaking.

“What’s wrong?”

My stomach folded in half, and in half again, the way you fold and fold a dollar bill into a tiny, lumpy square. “That is rape. Rape is never funny.” I was shrill. “Never funny.” I remembered the car, the light, his greasy hair, my vomit in the gutter, my wet mattress. My isolation.

“I was raped,” I told him. I had no trouble saying it. I was absolutely clear. The frat-bro video and my questioning son pulled the truth from me. I wasn’t bionic, but I felt power in saying the words. I needed my son to know, he had to know, not that I was raped, but that he could never pretend rape is funny, he could never pretend that no means yes, or that silence means yes.

I wish I’d checked to see how he was doing after I left him holding my story. I wish I’d been calm and considered when I spoke. Did he have questions about what he’d seen on his screen or what I’d said? I could’ve told him that for years I carried so much shame. And then, slowly I began to feel real tenderness for the girl who smiled up at the older man in the backyard, the girl who accepted the red Solo cup, even said thank you because he’d made her feel worthy.

“I was raped,” I told him. I had no trouble saying it. I was absolutely clear. The frat-bro video and my questioning son pulled the truth from me. I wasn’t bionic, but I felt power in saying the words. I needed my son to know, he had to know, not that I was raped, but that he could never pretend rape is funny, he could never pretend that no means yes, or that silence means yes.

I wish my mom had explained to me something about her pleasure, anger, silence, or resignation when she closed the front door behind the men. But maybe that was too much to ask from a woman struggling to love herself when men didn’t. A woman who perhaps was pushing back her own isolation. I felt tenderness toward this woman, my mother, as well.

Years later, while home on winter break from college, my son told me that my revealing my rape the way I had “was some bad-ass parenting.” I straightened my spine. It’s not often, in my experience, that adult children lay on the accolades. He told me he’d shared the story in his dorm, in a conversation around consent, which are thankfully common now. It caused a pause in the conversation, for his friends to consider. That moment of me sharing me had landed in a room full of young men.

I’ve never told my mother I was raped, and I don’t know if she was ever raped. I can picture her smoking and furrowing her brow at the counter with a cup of coffee, planning her week, making her list, grocery shop, pay bills, grade papers, plan lessons, go to the gym, dry cleaners, call her sister-in-law. On Monday mornings my mother modeled for me the truth that disappointment is bearable and not the end of the story.

My childhood fears all came to pass. I failed tests, got lost in a department store. I’m still afraid of snakes. And I was raped. If my son ever thinks back on us watching the video in his room that day, I believe he understands the truth that pain has long arms, and that pain is not the end of anyone’s story. Trauma, when you speak it, is survivable. The worst thing a woman can be is silent.

I’m floored. The writing is tight and the emotional grip tighter. I have grappled with whether and how to tell my daughters I was raped. They’re 14 and 10 now. This example is startling and empowering. The affirmation from your son is just the repair that the daring announcement needed… and so much more. “Psychological auto-immune disorder” is a very compelling term. I think I’ll be meditating on this for a long while.

What a powerful story. What a wonderful son.