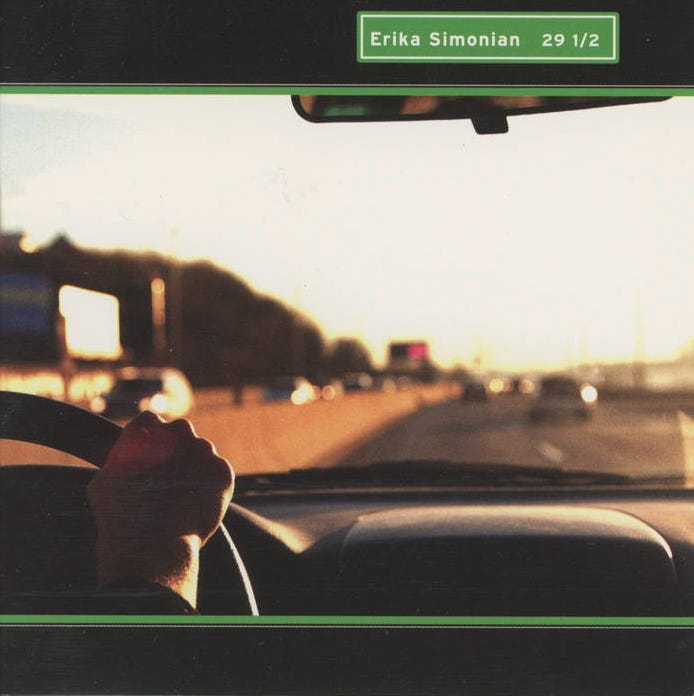

The Beginning, The Middle, and The End of 29-and-1/2

Erika Simonian looks back on making music with her band from the early aughts, touring with her mom, and finally parting with a box of the band's CDs.

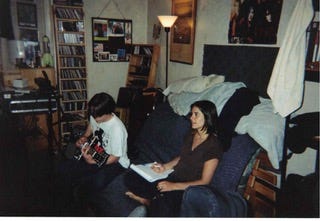

In 2000, my friend and talented engineer, Richard, suggested that I come spend a week at his home recording studio in Boston. I could crash on his couch and record five songs, and he’d get to acquaint himself with ProTools, Version God-Knows-What. Lately, I’d been drifting; the band in which I’d invested all my creative energy had fallen apart because too many band members wanted to be the boss, and no one of us was willing to cede ground to any other. It was the typical ego tangle plaguing many quasi-professional rock outfits. After having put what money I had into said band’s recording, I was broke.

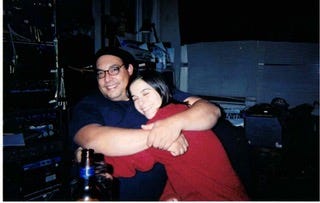

Richard’s gift succeeded in its mission. He produced a beautiful sounding record, and the project lifted me up, steeping me in the creative process after a crushing disappointment. We went deep and added six more tunes to the original promised five. We had an album! It documented a handful of my songs, all written over a span of five years.

I loved—and twenty-five years later still love—this record. It serves, like all records of events, as a diary entry, and this one, a document of my youth. Like any diary, it now conjures a mixture of sheer embarrassment with some amount of nostalgic admiration. It’s rife with lush guitars, a kickin’ rockabilly solo, and of course, some super-powered female anger, which I can forever get behind, but can no longer reproduce. That’s simply a vitality issue.

When “29 1/2” came out, I celebrated its release at a local club called Pete’s Candy Store in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. My friend Todd, who was the guitarist from my defunct previous band, joined me on stage. Todd had come to Boston to record with us for a few days, probably because he also had nothing better to do, post-band-breakup. His vocals and guitar tracks on the recording gave it a beautiful polish that I would not have achieved without him Together, we played a few regional shows in support of the record. Soon afterward, I planned a solo acoustic tour for the west coast. When I mentioned this to my mother, it appeared to concern her.

“But where will you stay?”

I loved—and twenty-five years later still love—this record. It serves, like all records of events, as a diary entry, and this one, a document of my youth. Like any diary, it now conjures a mixture of sheer embarrassment with some amount of nostalgic admiration. It’s rife with lush guitars, a kickin’ rockabilly solo, and of course, some super-powered female anger, which I can forever get behind, but can no longer reproduce. That’s simply a vitality issue.

When I reported that I had a network of friends-of-friends from San Diego to Seattle who’d said I could sleep on their couches, she either saw an opportunity for herself, or possibly wanted to protect me from this catch-as-catch-can, sleep-wherever-the-heck solo woman journey, or both.

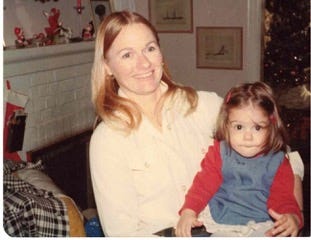

“Ok, I’ll go with you,” she responded, as if I’d asked. “We can stay with my high school friend in southern California, and you have Jen in Santa Cruz, Chris in San Francisco, then we’ve got Christa in Portland….” As we proceeded to compile our list, we realized this was a viable plan, and within a few months the tour was booked.

I flew out first, meeting my mother after the first couple of shows. My initial show had me opening up for the mystical Tom Brousseau. It was the first time I’d ever heard him perform and I was appropriately blown away. Here I was, absolutely batting out of my league, but I didn’t care. I felt as if I were on a magical high, a career upswing; I studied and immersed myself in these powerful performances. I gave him a CD.

Following that kick-off, the mother-daughter road trip began at LAX, where I picked my mother up in the rental car and immediately told her all about this musician from North Dakota with a voice like Jimmy Scott. My mom, who was a singular mix of control freak and more of a rebel than you, me or anyone we know, pretended to listen to me while securing her place behind the wheel. I assume it was her anxiety about being in the passenger seat on winding 101 that propelled her to take the lead. Since this was pre-GPS and we had only AAA and the Texaco Road Maps to illustrate the route that we’d meticulously highlighted prior to our trip, I was responsible for navigating.

In the tight streets of Whittier, California, she asked, “Do we need to make a U-turn here?”

“I wouldn’t,” I said, implying that we might wait to make a right and then another, until we were back on track. But I barely had the words formed in my mind before she whipped the car around in the middle of the boulevard, running up over the curb.

“Well, I know you wouldn’t…” she said impatiently, hitting the accelerator.

Day by day, we made our way up the coast. On one of our long stretches to the next stop, and with a couple of days before the next show, we afforded ourselves the luxury of the scenic, coastal route. This evening, she suddenly pulled over to the side of the road along the California coast. Ah, I thought, she finally needs a break. Swiftly, she popped the trunk and stepped out, rounding to the rear of the car, from where she pulled out two bottles—one of vodka and the other of orange juice—and magically produced two plastic cups from her purse. She mixed the drink clumsily and handed one to me, before pouring the other for herself. We returned to the front seat, where we watched the sun descend brilliantly into the Pacific before moving on to a seaside restaurant and laughing until our sides practically split. I don’t remember what particularly set that in motion and it doesn’t matter; it was just a classic case of ‘the giggles’.

Each night, my mother diligently sat at the merch table, selling one or two CDs to whomever came out for these sparsely-attended shows, and running herself back and forth to the bar to get the appropriate amount of change for buyers. I had tee-shirts made for the “Where Can I Get A Good Bagel Around Here?” Tour, my west coast joke that wasn’t really funny, listing the stops in the cities on the tour, with the cliched SOLD OUT stamp across the back. I no longer have any of those, so I either sold them out or gave them all away.

The mother-daughter road trip began at LAX, where I picked my mother up in the rental car and immediately told her all about this musician from North Dakota with a voice like Jimmy Scott. My mom, who was a singular mix of control freak and more of a rebel than you, me or anyone we know, pretended to listen to me while securing her place behind the wheel. I assume it was her anxiety about being in the passenger seat on winding 101 that propelled her to take the lead.

In the eighteen years that followed, I stored the excess boxes of “29 1/2” CDs in my mother’s basement. On visits home, she’d occasionally ask when I’d be taking them, but of course, my New York City solo-closet, one-bedroom apartment didn’t afford me the space to store excess stuff. Meanwhile, I knew in that in today’s streaming music era, there was little chance I was ever going to unload those CDs.

Before my mother sold her house in South Jersey to move into an apartment six years ago, I traveled there for a long weekend to sort through my things. At 47 then, I was nearly two decades past that album’s release, and during that span, digital music subscriptions had long-eclipsed CD ownership. On my drive down, I brainstormed ideas about what to do with the CDs, at that point, mostly not wanting to throw that amount of plastic into a landfill. Other family members descended to help with the moving-out effort, and we all spent the weekend clearing and cleaning, yet carefully avoiding my three boxes of untouched, shrink-wrapped CDs. On Monday morning, when I heard the garbage crew approaching, I watched my mother dash outside, making a purposeful walk toward the truck.

“I struck a deal with the guys,” she said, wiping her feet and closing the front door behind her. “They said you can put all the CDs out and they’ll come back later when they’re picking up recycling.”

In the eighteen years that followed, I stored the excess boxes of “29 1/2” CDs in my mother’s basement. On visits home, she’d occasionally ask when I’d be taking them, but of course, my New York City solo-closet, one-bedroom apartment didn’t afford me the space to store excess stuff. Meanwhile, I knew in that in today’s streaming music era, there was little chance I was ever going to unload those CDs.

I wondered what actual “deal” my mom struck, but I didn’t ask, because almost twenty years later, this felt like a triumphant ending. Too afraid to press her for details on whether or not these records would actually be recycled, I kept my mouth shut; I couldn’t risk the possibly plan-thwarting truth. Instead, I nodded and hauled box after box of CDs to the curb. I plucked only two wrapped copies out of an open box, deciding those would be all I’d ever need.

Looking at the boxes that sat so innocently and intactly at the edge of my mother’s cul-de-sac, I stood, pointedly holding the moment. I realized how grateful I feel to all the people who helped out with this endeavor, for no money at all. That, in and of itself, spoke to our youth. It’s what we did then: played, sang, whatever-ed on each other’s records. And then there’s my mother; a good one supports your dream when it’s happening, and helps you close it up when it’s run its course. My own life is lighter without those plastic CDs, but do I hope that somewhere in a South Jersey dump, a sanitation worker is listening to “Long Day in a Short Skirt”? I really do.

Long day in a short skirt--love it! I bet your memoir will be a fun read. And what a great mom. Lucky you!