The Burden of Leaving

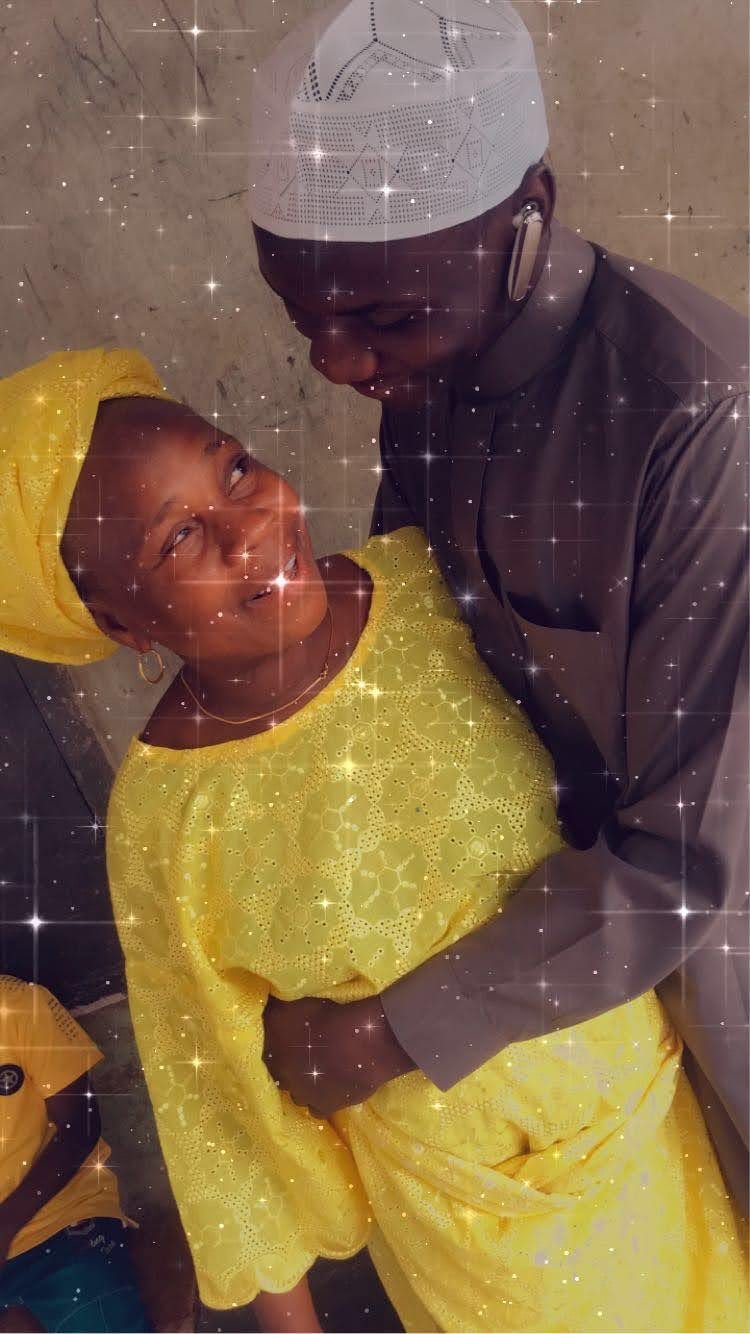

Ahmad Adedimeji Amobi considers what it means for his long widowed mother each time he departs for school.

I have packed my clothes in my bag. I have put the exfoliating scrub my mother bought for me inside the pack that contains my foodstuff. I have ruffled garri and sugar pack to the bottom of the sack. The tins of Three Crowns Powder Milk and Milo have also been packed together with the bottles filled with palm oil. My brush, my hair cream, my toothbrush, my Vaseline and my spray, all forced into one nylon bag, are ruffled inside the sack. What remains now is tying the sack. Tying the sack would mean I have perfectly completed my ritual of leaving.

But reluctance has crept into my body, making me drag my feet to the floor of my room. I’ve left before, I always leave when it is time, but this strange reluctance to tie the sack comes as constantly as my leaving itself. I understand what it means, this reluctance. It alludes to history, a scratch of memory, of memory that is folded into packs of other memories.

I’ve left before, I always leave when it is time, but this strange reluctance to tie the sack comes as constantly as my leaving itself.

Every time I’m about to leave my mother for school, this reluctant feeling arrives and reminds me of what my leaving means to her. The first time I left for school, as an undergraduate at the University of Ilorin, I watched tears burst from her eyes as she melancholily waved at me, while the bike man rode me out of her sight. I buried my head in my palms and sobbed into them.

Before that moment, it had never occurred to me that my mother could cry for me. I had watched her cry when I was in secondary school and a report came, saying that I was one of the most troublesome students in my class; or when the proprietor of my school drove me home himself to inform her that I had thrown a stone to crack his windshield. I had heard her saying, while sobbing, that she wished she had flushed me out. Until the day I was leaving for school, I had never realized how much I meant to her, how much my being around her meant to her.

All these memories come back to me whenever I’m leaving her. She won’t cry today. She won’t. This is my fourth year as an undergraduate; she’s used to seeing me leave after spending a few months with her. But I see that shade of missing, that crack of her other face that doesn’t want me to leave, as I turn my back to go.

Every time I recall these scenes, it evokes the story of how she lost my father. I didn’t know my mother was so soft at handling departing. Twenty-two years ago, my father departed from her—from life, from this world—when she was young, and still carrying me inside her. My father married my mother when he was old, and death was lurking in the distance. Though he couldn’t see it, he was already at the age when death could come in without knocking. My father died at age 84, and I was born shortly after his death. Every time I intend to leave, I always imagine how it must have felt for her: handling my father’s departure while also expecting my arrival.

Until the day I was leaving for school, I had never realized how much I meant to her, how much my being around her meant to her.

My mother’s senior wives—the wives my father married before her—died before my father did. The loneliness would’ve been softer if they were alive. My mother told me that they all shared a tight bond despite being much older than her. My mother gave birth to nine of us, but she was so young when my father died. She doesn’t know her own exact age because she doesn’t know her birthday, but when I calculated the age of her first born, my eldest brother, with the year she thinks my father married her, she was roughly in her early thirties when my father died.

Widowhood was tough for my mother. As little as I was, I still carry the memories of how hard it was for her to care for and cater to her nine children. I remember the day she broke into tears when my immediate elder brother, who is a barrister now, was sent back home for owing school fees. That was the very first time any of her children would be sent home for school fees. My mother didn’t go to school herself, but she vowed to immerse her children into western and Arabic education. My mother still asks me, even at 22, if I’ve observed my prayers. Any time we speak on the phone, she still asks whether I’ve read my books. She still tells me, every time, to choose my words carefully when I speak, as though what I have to say could be the last sentence to fall out of my mouth. You know, we are always remembered by our last utterance, my mother would tell me.

When I think about my mother’s life as a widow, it makes me wish there’d be a global law enacted prohibiting marriage between a man who already has two or three wives, and a woman in her early adulthood. Or between an old man and a much younger woman. In Nigeria, child marriage is as common as inflation on every commodity in the country. Though death is not age-predictable, there is no clearly foreseeable death for a young person. You see a man approaching his grave marrying a teenage girl. After the old man’s death, the young widowed soul is left to wander, because most married women, like my mother, always have this conviction of not making themselves open to any other man after their husband’s demise. Widowhood was tough for my mother because she believed she’d married a man she was going to spend the rest of her life with.

You see a man approaching his grave marrying a teenage girl. After the old man’s death, the young widowed soul is left to wander…

At an early point in writing this essay, I searched online for what it means to be a widow in Nigeria. Later, I deleted Nigeria and replaced it with Africa. I believe my mother’s story does not exist in isolation. I wanted to know how common it is. I came across an essay by Tolulope Ajiboye in Ms. Magazine documenting the experiences of widows across African countries with their “dehumanizing cultural and ritual practices,” which are clearly always detrimental to women. But I couldn’t find one that documents an experience quite like my mother’s. An experience of a Muslimah, a pregnant widow, and a mother.

A report by the United Nations on International Widows’ Day caught my attention. On the cover was a photo of a woman with her child strapped to her back, captioned: “Hawa was pregnant when she lost her husband and the rest of her family in the fighting in the Central African Republic.” Hawa, like my mother, is a Muslimah, a widow and a mother. Of course, the report didn’t cover Hawa’s story specifically, but three points in the report haunt me; that there are an estimated 258 million widows around the world, and nearly one in ten live in extreme poverty; that in some parts of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, for instance, it is reported that around 50 percent of women are widows; and that widows are coerced into degrading and even life-threatening traditional practices, like shaving their heads bald as part of burial and mourning rites. I still haven’t gotten over these details because I have a firsthand experience of what they mean. The biggest take-away from the report that I was able to decipher was that almost every widow experiences traumatic episodes after her husband’s death.

In Islam, women are excluded from certain cultural practices, but not 'Iddah, a period of four months and ten days after a husband's death, during which a widow is not allowed to remarry. But religious observance is not necessarily an indication of goodness; even in pious families like mine, widows are often subjected to grudges and hostility from family members.

Religious observance is not necessarily an indication of goodness; even in pious families like mine, widows are often subjected to grudges and hostility from family members.

Before my father died, he told my mother to point at any portion of his wealth that she wanted (whatever that even means) because tomorrow he might not be around, and family issues might be exhumed, but my mother refused. She wasn’t expecting him to die even a decade later than he did. What it means to be a widow in an extended family is that the moment your husband dies, you become property to the family, and your children do not belong to you. Your decisions do not belong to you.

My mother wanted to break this convention. She wanted her children to belong to her because she understood what her children would become after her husband’s death. They would become seeds planted into different soils. One uncle in Lagos would want your brother to come stay with him. Another in Oyo thinks he’s the best to nurture you. She didn’t want her children to become flares of light shooting and fading out of Christmas fireworks. In the beginning, it always seems right. But the consequence is watching your children grow to become what you don’t want. My mother held her children around, provided everything she could for them and watched us grow, to become wonders.

What makes my leaving hard is knowing the assurance that my coming to this world gave her. My being inside her whilst she provided for my elder siblings, and later giving birth to me, assured her that she was a force, capable of anything.