The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #80: Rebe Huntman

"I began this memoir with three questions that were rich and deep enough to sustain me over the years it took to turn them over in the light that became this book."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

Here’s the 80th installment, featuring memoirist, essayist, dancer and poet . -Sari Botton

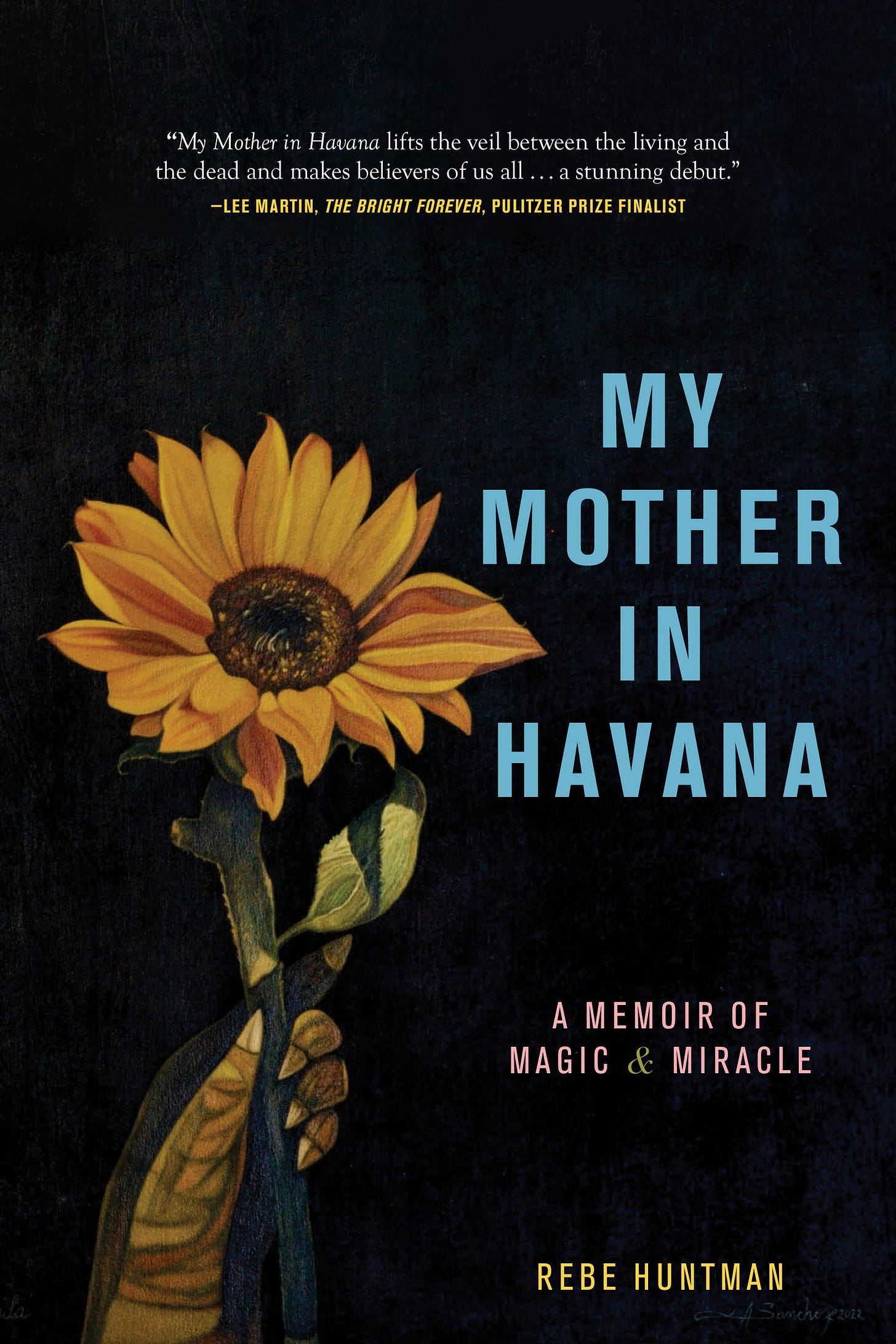

Rebe Huntman is a memoirist, essayist, dancer and poet who writes at the intersections of feminism, world religion and spirituality, and the author of My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle. For over a decade she directed Chicago’s award-winning Danza Viva Center for World Dance, Art & Music and its dance company, One World Dance Theater. She collaborates with native artists in Cuba and South America, has been featured in Latina Magazine, Chicago Magazine, and the Chicago Tribune, and on Fox and ABC. A Macondo fellow and recipient of an Ohio Individual Excellence award, Rebe has been awarded grants and fellowships for her work on My Mother in Havana from The Virginia Center for Creative Arts, Ragdale Foundation, PLAYA Artist Residency, Hambidge Center, and Brush Creek Foundation. She holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from The Ohio State University and lives in Delaware, Ohio and San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Both e’s in her name are long. Find her at www.rebehuntman.com and on Instagram @rebehuntman.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I have been living a creative life—as a dancer, visual artist, book maker and teacher— for sixty years, and I’ve dedicated the last twelve of them to writing.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle. It was published February 18th.

What number book is this for you?

With poems, essays & stories published in places like The Southern Review, CRAFT Literary, The Missouri Review, The Cincinnati Review, Ninth Letter, and The Pinch, My Mother in Havana is my first book-length publication.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

I think of My Mother in Havana as a hybrid memoir because it tests the edges of the genre, layering memory with elements of journalism and mythology, spiritual inquiry, and even fiction to produce a work that author Heather Lanier has likened to a trinity, calling it “an engaging travel narrative, a moving grief excavation, and an awe-inducing spiritual journey.” The result is a sort of palimpsest in which each layer builds upon the other to create a story that is larger, deeper, and richer in meaning than the sum of its parts.

It is impossible to separate my origin story as a writer from my life as a dancer and choreographer. I am drawn to the physicality of language: the way it moves, like the body in dance, allowing us to capture the way the world comes at us as more than one thing. It is this in-betweenness that drives My Mother in Havana’s narrator as she moves between the worlds of Ohio and Cuba, between the spiritual practices of Santería and Folk Catholicism and Spiritism, between the stories of her biological mother and the stories of Cuba’s spiritual mothers, Our Lady of Charity and Ochún.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

“A daughter’s search for her deceased mother brings her face to face with the gods, ghosts, and saints of Cuba. In this dazzling and lyrical debut memoir, the author reimagines the classic pilgrimage quest as she is drawn into the mysteries of the gods and saints of modern-day Cuba. Interweaving the story of her search to reconnect with her mother, thirty years after her death, with the search for the sacred feminine, Huntman leads the reader into a world of séance and sacrifice, pilgrimage and dance, which both resurrect her mother and bring Huntman face to face with a larger version of herself.”

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

It is impossible to separate my origin story as a writer from my life as a dancer and choreographer. I am drawn to the physicality of language: the way it moves, like the body in dance, allowing us to capture the way the world comes at us as more than one thing. It is this in-betweenness that drives My Mother in Havana’s narrator as she moves between the worlds of Ohio and Cuba, between the spiritual practices of Santería and Folk Catholicism and Spiritism, between the stories of her biological mother and the stories of Cuba’s spiritual mothers, Our Lady of Charity and Ochún. But the link between dance and writing is even more literal when it comes to this book, for it was when I first visited Cuba in 2004 to collaborate with native choreographers that I was introduced to the dances that celebrate the Afro-Cuban gods of Santería and the divine mothers that stand at their center.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

I wrote the first draft of My Mother in Havana in a mad fever. I’d just returned from Cuba and wanted to commit the experiences of that pilgrimage as vividly and honestly as possible to the page. But it took six years to braid the remaining elements into that narrative. I scoured family archives and letters for backstory; puzzled over how and where to insert memories of my mother into the more linear narrative of my trip to Cuba. Devoured books about the mythology and practices of Santería and the Afro-Cuban gods known as the oricha. And I made numerous return trips to Cuba to scour archives and deepen my practice with the rituals that lie at the heart of this book. Perhaps the most challenging aspect was to turn off the part of my brain that wants instant results and make room for the process to take as long as it needed to take.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

As a true story, I wanted it to have real names and identifying details. And, as an outsider to Cuban culture, I felt it was crucial that I get those details right. To that end, I made multiple return trips to Cuba to visit archives and further immerse myself in the Santería, Spiritist, and Folk Catholic traditions that lie at the heart of the book. I fact-checked details with many of the characters that populate the book. I was lucky to be given access to archives and invited to share my manuscript at Santiago de Cuba’s International Colloquium on Popular Religions, where I received feedback from leading Cuban and international scholars.

With my US characters, I asked family and loved ones to corroborate memories. I particularly wanted to make sure that my son and my now-husband Rick were comfortable with anything I’d chosen to write about them. Both declined my invitation, and my husband cited his reason as not wanting to influence what I’d chosen to write.

Wild was the book I studied most closely, patterning my structure, in which each chapter—except for the first—begins on the pilgrimage to Cuba after the way Strayed begins each chapter on the Pacific Crest Trail. This clear linear narrative created the scaffolding around which I could then braid memories, mythology, research, and inquiry to create a multi-layered, lyrical memoir that moves elegantly across time and space and thought.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

My Mother in Havana has many literary godparents: lyricists like Lia Purpura and Eula Biss and Brenda Miller who gifted me models for the kind of structural and linguistic choices that make their pages sing. Toni Morrison for her gorgeous blending of the spiritual and the mundane. James Baldwin for the rigor of his intellectual inquiry. And memoirists like Cheryl Strayed (Wild), Helen MacDonald (H is for Hawk), and Doireann Ní Ghríofa (A Ghost in the Throat), whose memoirs braid excavations of grief with a parallel quest that allows them to transform that grief.

Of those memoirs, Wild was the book I studied most closely, patterning my structure, in which each chapter—except for the first—begins on the pilgrimage to Cuba after the way Strayed begins each chapter on the Pacific Crest Trail. This clear linear narrative created the scaffolding around which I could then braid memories, mythology, research, and inquiry to create a multi-layered, lyrical memoir that moves elegantly across time and space and thought.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Writing a book is a marathon, not a sprint, and it’s important to fall head over heels in love with the thing you’re writing about because you’re going to spend a lot of time with the material. It is important for me to write about big questions that don’t have easy answers because it’s the act of following those questions that leads both me as the writer and my reader into areas of mystery and surprise. I began this memoir with three questions that were rich and deep enough to sustain me over the years it took to turn them over in the light that became this book. The first: If my mother has been dead for thirty years, and if, in that time, I have all but forgotten her, then what is it that I’m missing when I say that I miss my mother? The second: How can I connect with that larger maternal spiritual energy? And the third: How might connecting with that larger spiritual energy lead me back to my own mother?

My advice about falling in love goes for process, too, because if you’re going to enter into a marathon you might as well enjoy the ride. I love reading craft books to see how other authors and artists approach the creative process. Personal favorites include Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic (which is such a refreshing primer in trusting our intuition as creators) and Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit (in which she gave me permission to think about writing a book like a building process). My final advice would be to ask for help when and if you need it. As writers, we depend on outside readers to help us see our blindspots. And I’m a huge believer in working with a developmental editor who can help take your great writing and make it even better.

What do you love about writing?

For me, the act of writing is an act of saying I am here. This is what I stand for. This is what I find beautiful. Important. Worth paying attention to. And there is a gesture in reaching out to the world through that act of attention and saying: Won’t you pay attention alongside me? In writing this book, I found myself addressing the reader directly because I wanted to create that intimacy of standing alongside them, of sharing those things that have lived in my heart and bones: the Afro-Cuban religions of Santería and Folk Catholicism and Spiritism and the power of those religions to help us find our way back to our lost beloveds; a way to know Cuba—not through the more masculine lens of pirates and revolutionaries, Hemingway, and classic cars, but through the radical lens of the sacred & the feminine.

My Mother in Havana is a map that shows us how to push past the five senses to claim a more mythic life. A way to find our way back to those things we understood clearly as a child. An invitation to connect with the deep & long story of our lives and our ancestors. Chase those ancient rhythms of conga & shekere into a world of séance and pilgrimage, sacrifice & sacred dance. I wanted to say: Look at these great spiritual mothers, Ochún and Our Lady of Charity: both of them as real as the woman sitting next to you on the bus, and as mysterious & vast as the deepest river of your being. A feminine path to the divine that has been largely buried in today’s rush toward materialism & consumption. A soft voice in our ear reassuring us that everything IS going to be all right.

What frustrates you about writing?

The very thing I love about writing—all that focused time and devotion and mystery—is also what can frustrate me. Because in order to write, we paradoxically have to let go of certainty and wade into the unknown to find the sort of deep and resonant truth that’s not available at the surface. I have to lay down a lot of words before I can find my way through them. And that initial mess can be very disconcerting. It can feel like you will never find your way to a polished draft.

There are many dark nights of the soul when self-doubt creeps in. And the only way to get to the other side is to keep moving. Because the flip side of fear and uncertainty is a sense of mystery and surprise. And the reward for wading through mystery and surprise is transformation. I am not the same person who began writing this book. I have been transformed by what I learned in writing it. And my hope is that, by bringing my reader along with me, they too will be transformed.

What about writing surprises you?

The way seemingly disparate threads of thought and research start to find their way to one another while you’re doing something else. I keep a journal next to my bed and couch to catch the aha moments that seem to break through when I’m resting. I carry my cell phone with me when I run so I can catch the thoughts that begin to bubble up on a voice memo. Some of my biggest breakthroughs came when I was doing something else: the idea to bring the historical characters that anchor my book to life came when I was reading a book about the history of El Cobre. The scenes in which I imagine into my parents’ 1951 trip to Cuba became possible only after I discovered four Polaroids that documented their trip. The most important thing is to start the process of writing and trust that your subconscious will meet you and carry you through.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

In The Artist’s Joy, creativity coach Merideth Hite Estevez says that the first thing she asks her clients is what they’ve eaten for lunch. That’s because it is easy to forget when we are creating that we are human beings with physical needs. That our minds and bodies are the instruments through which we create, and those instruments require care. And so, while my writing processes and routines have changed over the years, I try always to consciously build my days around both my writing and the routines and habits that support that writing. And because we live in a world that puts so many demands on our time, I approach each month’s calendar by first blocking out the hours I’ll devote to writing and to caring for the human who does the writing. From there, everything else constellates around those first decisions.

The very thing I love about writing—all that focused time and devotion and mystery—is also what can frustrate me. Because in order to write, we paradoxically have to let go of certainty and wade into the unknown to find the sort of deep and resonant truth that’s not available at the surface. I have to lay down a lot of words before I can find my way through them. And that initial mess can be very disconcerting. It can feel like you will never find your way to a polished draft.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

With this book, I gave myself a devotional practice of folding origami cranes. When I was in high school and my mother was fighting cancer, a Japanese friend suggested we fold origami cranes to hang above her hospital bed. She told us legend had it that if we folded a thousand cranes we could surely save her. It’s a lot of work to fold that many birds and we only made it to a hundred. And so, 30 years later, while I was working on My Mother in Havana, I gave myself the task of folding a thousand birds. As I worked, my hands remembered those first folds I made all those years ago, and that allowed me to tap into memories that I in turn folded into the pages of the book.

Similarly, running, walking and knitting all support my general writing practice because they give my mind a chance to wander constructively, to seek and make connections between the various threads I’m thinking about in my writing. Knitting in particular underscores the physical nature of writing because it gives me a tactile, physical sense of weaving together actual threads. I also practice a form of Julia Cameron’s morning pages, which allows me to sort out my thinking on the page. And I make my own journals. Like knitting, the process of binding and collaging their covers, gives me a tactile outlet that reminds me that the process of writing is a process more akin to building than just about anything else.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I’ve got a couple of projects that I’m excited to start in on—novels based on the stories of my grandmothers. A work of fiction that dives into the worlds of the Nordic gods. But first, I have a poetry collection that is almost ready to find a publisher. Like My Mother in Havana, the poems are a cinematic exploration of the forces that collaborate in the shaping of what it is to be woman.

Unlike My Mother in Havana, the settings of that inquiry widen to include a kaleidoscopic catalog of Midwestern bowling alleys and 1950s burlesque clubs, mermaid meet and greets, a dead mother’s tour through 1980s Russia, and of course the mother saints and goddesses of Cuba. Tentatively titled Zinnias in My Mother’s Vase, the collection is both a container for wildness and a portal between generations—an invitation to join the author as she and the concentric circles that bloom from that central eye—ancestors, role models, & ultimately that ineffable, unnamable force that animates life itself—weigh in on the feminine body. Is it object? Is it vessel? Or is it a cosmos both contained by & too vast to be contained by any vessel?

Thank you, Rebe and Sari! This is wonderful - in particular I love the comment about the physicality of language, and this: "Because the flip side of fear and uncertainty is a sense of mystery and surprise. And the reward for wading through mystery and surprise is transformation."

It's important to fall head over heels in love with the thing you are writing about...I can't think of better advice for a writer. For this writer. Thank you!