The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #25: Hyeseung Song

"'Docile' is my journey to form an identity outside the model minority myth, contend with mental illness, and find redemption in art. My agent likes to call it the Asian 'Girl, Interrupted.'"

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

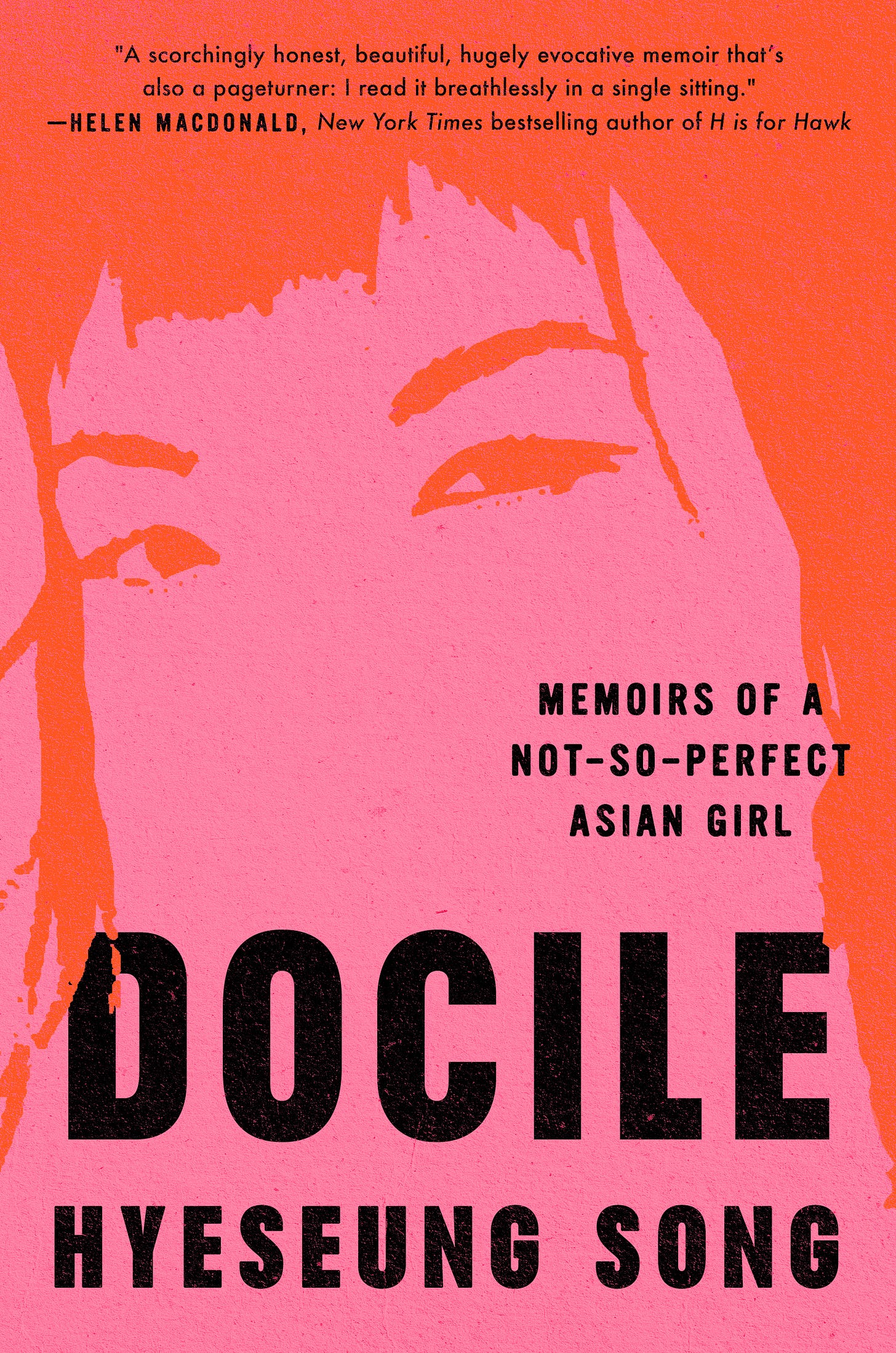

Here’s the twenty-fifth installment, featuring , author of Docile: Memoirs of a Not-So-Perfect Asian Girl. -Sari Botton

Hyeseung Song is a first-generation Korean American painter and the author of Docile: Memoirs of a Not-So-Perfect Asian Girl. She lives in Brooklyn and upstate New York. Learn more about her at hyeseungsong.com. Instagram/X: @hyeseungs Tiktok: @noturdocile

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I just turned 46 and have been writing since childhood. As an immigrant in Texas, I grew up largely around native speakers of English, my second language. In stories, plays, screenplays and a novel which will never see the light of day, I tried to capture its cadence and rhythms, its mores and pathos.

I’ve been a visual artist since my mid-twenties and wrote my memoir while I was making and selling paintings for a living. It wasn’t until relatively recently, when I got my book deal at the end of 2021, that I would say that I became a professional writer.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Docile: Memoirs of a Not-So-Perfect Asian Girl is out on July 16, with Simon & Schuster.

What number book is this for you?

It is lucky number one.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

Docile is a memoir—its structure took its inspiration from novels.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Docile is a coming-of-age memoir about growing up as a first-generation Korean American in Texas and earning visibility in my not-so model family and in white society through academic achievement—which works sort of okay until I’m 25 and a graduate student at Harvard, when I wake up one morning in a psychiatric hospital, just having survived a suicide attempt. In the hospital, I come to a reckoning about my self-worth. I decide I must choose and heal myself. I leave the hospital, leave Harvard, disappoint my parents, move to New York and become an artist, finding unconditional self-expression in art. Docile is my journey to form an identity outside the model minority myth, contend with mental illness, and find redemption in art. My agent likes to call it the Asian Girl, Interrupted.

Docile is a coming-of-age memoir about growing up as a first-generation Korean American in Texas and earning visibility in my not-so model family and in white society through academic achievement—which works sort of okay until I’m 25 and a graduate student at Harvard, when I wake up one morning in a psychiatric hospital, just having survived a suicide attempt.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I came to writing as a student and observer of cultures in which I was an outsider. As a young person, I wrote first to imitate others, then to understand myself.

I was strongly encouraged to leave college when I was struggling with my mental health. When I returned, having been sent to Korea as a bootstrapping measure by my parents, I had a new, albeit inchoate understanding of my racial identity as a Korean American. I applied to the creative writing workshops at my alma mater and began writing short stories about the most maddening people I knew: my family. Curiosity took me to the page; I wanted to try to understand the internal drive of the people I’d grown up with and whose spectacular influence I felt on my life. What I was having was my first real experience of how writing can provide clarification.

I also didn’t know what I was writing were the first chapters of Docile.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

I am a painter by trade and wrote Docile in fits and spurts over two decades. The hardest part of writing it was changing—and seeing the world change—as I wrote.

Publication, on the other hand, happened fast. Docile lives in the intersection of race and mental illness. It’s a young Asian American woman revealing how she is not so model—because she has a serious mental illness, because she is human. In writing Docile, I left everything on the page. All of it.

The relative scarcity of AAPI mental health memoirs makes sense given the reality behind AAPI mental health: Asian Americans believe mental health stigma extends to their families, which makes it harder to be open about difficulties. They are less likely than other racial groups to utilize counseling services, and when they do, their symptoms, understandably, are further gone. Finally, the number one cause of death among young Asian American adults ages 15-24 is suicide, a totally staggering statistic that frankly, not enough people know about.

My memoir is in some ways a response to, but also an illustration of, these statistics. I never break the fourth wall in Docile. My own very second-order ideas about AAPI mental health are instantiated in the actions and thoughts of the characters. It was good for Docile but a sad reality about the vacuum in publishing for these intersectional stories, that it was picked up quickly on sub.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

I changed nearly all names and identifying details. A year ago when the manuscript was nearing completion, I sent pages to the people whom I cared to have a good relationship with after the book came out. I did say that this wasn’t an invitation to collaborate but rather a chance to process together anything that they wanted. No one requested changes or processing, with the exception of one family member, who had a factual correction and was otherwise very angry about the fact that I wrote about the family at all (this person did not read the entire manuscript).

My father, who is such a big character in the book and also has the last word, has always had access to the manuscript, but refuses to engage with Docile. Giving me a wide berth is his attempt at respecting my art when he is afraid it might hurt him. To many in his generation of the Korean diaspora, American memoir is a bizarre baby—my father has little understanding of the difference between memoir and autobiography, and expects a press release or greatest hits parade of family achievements.

The relative scarcity of AAPI mental health memoirs makes sense given the reality behind AAPI mental health: Asian Americans believe mental health stigma extends to their families, which makes it harder to be open about difficulties. They are less likely than other racial groups to utilize counseling services, and when they do, their symptoms, understandably, are further gone. The number one cause of death among young Asian American adults ages 15-24 is suicide, a totally staggering statistic that frankly, not enough people know about.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

Thankfully, in this culture of scarcity, inspiration is not a finite commodity. Many, many authors inspired me. Quickly: Rachel Cusk, George Eliot, Vivian Gornick, Cathy Park Hong as well as the generous authors who blurbed my book, including Grace M. Cho, Joanna Rakoff, Chloé Cooper Jones, Helen Macdonald, Kat Chow, Frances Cha, Rachel Yoder, Marie Myung-Ok Lee, and David Henry Hwang.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Don’t worry about the publication process yet; focus on the story. Do the emotional work that’s necessary to write memoir, be curious about your life, and don’t fret if while you’re writing about the past, if the present seeps in. It has to—understanding needs that distance.

When you do get to the publication process, take control, be a good student, and feel your power (your story is important) even though it’s a thorny industry to break into.

What do you love about writing?

Feeling powerful and fulsome, having agency and freedom. Expecting from the page nothing and everything.

What frustrates you about writing?

That it can take its own time. That you can feel you’ve learned things one day, and then realize you know nothing the next. That it is Sisyphean—you can push the boulder to the top of the hill and have written something good, then the boulder rolls down again, and the same problems are there in a different guise, for a different project for which your old solutions don’t apply. It’s actually a bit funny.

What about writing surprises you?

What surprises me the most about writing is how the process essentially flips the internal into the external—a river rushing towards the ocean. Even if you’re writing something you think you’ll never show anyone, the practice of shaping and ordering your thoughts and placing them into a container—that externalizing process metamorphoses those internal thoughts.

And then, if you do end up sharing those thoughts with someone else, the fact that we are two (or more) separate entities with our own particular minds, but we can still recognize the ocean for the river in the writing? That recognition never ceases to amaze me.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

I’m a morning person. I like to slide from my bed, to the coffeemaker, and then to my desk. I write first drafts by hand.

My father, who is such a big character in the book and also has the last word, has always had access to the manuscript, but refuses to engage with Docile. Giving me a wide berth is his attempt at respecting my art when he is afraid it might hurt him. To many in his generation of the Korean diaspora, American memoir is a bizarre baby—my father has little understanding of the difference between memoir and autobiography, and expects a press release or greatest hits parade of family achievements.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I’m a visual artist. I make mostly large-scale figurative paintings starting in realism and representation and then proceeding towards abstraction or even surrealism. The work is mainly about the parameters of creativity and what I call “psychological incipience,” the process by which we become the people we are meant to be.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

Yes, I’m writing a second memoir right now about mental health and the importance of metabolizing your emotions and about feeling your feelings. It is also about grief and art.

I loved this interview—so illuminating about the mental health issues facing the AAPI community. Can’t wait to read this for August book!

Excellent interview. I'm new to Substack, but I've started my own journey of writing my own memoir about processing the suicide of my immigrant Caribbean father. Hyeseung's POVs are definitely affirming that I'm moving along the right path. Thank you for sharing!