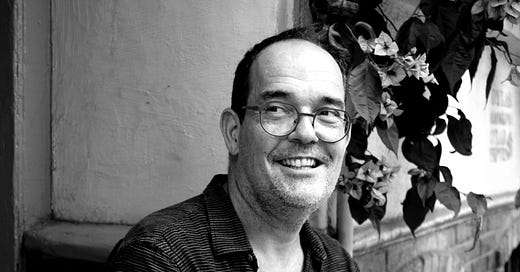

The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #76: Jeffrey Wade Gibbs

"Peril is a memoir exploring my father's suicide and its connection to the racial violence of south Georgia."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

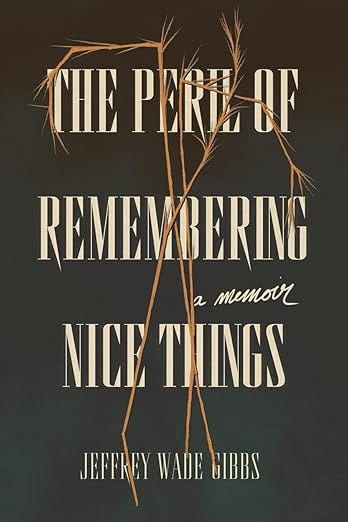

Here’s the 76th installment, featuring Jeffrey Wade Gibbs, author of The Peril of Remembering Nice Things: A Memoir . -Sari Botton

Jeffrey Wade Gibbs was born and raised in rural Florida, shuttling back and forth between his mother's people in Lakeland and his father's in the north central lake region. He grew up fishing, boating, and wandering the woods while learning the dark twists and turns of his Southern heritage at his father's side. He attended the University of Central Florida where he majored in creative writing and then left the South to teach English in Tokyo. Since then, he has made his way around the world, working as a teacher and writer in Japan, India, and now Turkey, where he lives with his wife and son.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I am 53 years old. Is that possible? Internally, I picture myself at about 34. I have been writing regularly since I was 9 when I launched a soap-opera spoof starring barely disguised versions of my friends. I wrote an episode a month for five years and distributed copies to a regular audience of about ten people. I always included a page asking readers for their detailed critiques which, amazingly, they supplied. It was great training.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

The Peril of Remembering Nice Things was published in October of 2024 with April Gloaming Press. The ebook version came out in January of 2025.

What number book is this for you?

Despite almost thirty years of trying to get one book or another published, this is my first one.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

This question scares me. I know a complicated answer renders the book unmarketable. I get it, people like to know what they are getting into and they don't patience for long-winded answers. So the short of it is, Peril is a memoir exploring my father's suicide and its connection to the racial violence of south Georgia.

It is also a piece of creative nonfiction. Incidents from my own life may form the spine of the story, but the flesh and other bones follow what fellow Substacker

calls a thought-arc, tracing the ruin of my father's life and his theatrical death to the racial violence of the South, in particular a lynching my grandmother told me she'd witnessed.In the book itself, I define Peril as a zuihitsu, a Japanese genre of writing that translates literally as "follow the pen." One Japanese dictionary defines it as “Taking your subjective feelings, memories, and things you have witnessed and surrendering them to the movement of the pen, making connections to produce a free-form text.” This free association is what appeals to me and what moves me closest to the truth when hunting my dad’s ghost, for in writing, I sometimes wander from memory to history, from me to him, from emotional impression to numerical data, from my life then as a boy in conservative rural Florida to my time in Japan, to now as a man married into a family of politically active Kurds in Turkey.

“The Peril of Remembering Nice Things blends family history and memoir in this unflinching exploration of the legacy of Southern racism. ‘So, why did your daddy kill himself?’ a family member asks the author in the opening lines of the book. This jarring question sets the stage for a Southern Gothic memoir in which Gibbs seeks to understand his father’s death by piecing together his own childhood in the South and his family’s connection to the 1921 lynching of John Henry Williams. It is an unflinching investigation guided by the heart.”

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Oh man, that's a tough one. I have been fortunate to have some extremely positive reviews from Kirkus, Foreword and the Independent Book Review. I have put together a pitch from their insight: The Peril of Remembering Nice Things blends family history and memoir in this unflinching exploration of the legacy of Southern racism. “So, why did your daddy kill himself?” a family member asks the author in the opening lines of the book. This jarring question sets the stage for a Southern Gothic memoir in which Gibbs seeks to understand his father’s death by piecing together his own childhood in the South and his family’s connection to the 1921 lynching of John Henry Williams. It is an unflinching investigation guided by the heart.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I don't remember not thinking of myself as a writer. My maternal grandmother taught me to read and when I was in first grade, I wrote a sequel to The Wizard of Oz because I wanted to see what happened next. I distributed the finished book (self-published of course) to my family.

Peril came about because I was haunted – my father's ghost kept poking me, and for that matter, so did John Henry Williams', the man who was lynched in Autreyville in 1921. Two people asked me seemingly unrelated questions at around the same time. One was my therapist, who after several long sessions explaining my father and his suicide, asked why I had never written about it. The other was my father-in-law, a Kurdish dissident. He spent three years in jail as a political prisoner – his crime was teaching Kurdish. In fact, he was arrested two months after my wife and I were married, and it left a traumatic mark on our early marriage. I remember feeling we could trust no one. The media smear campaign was intense, portraying every act of those arrested as terrorism.

In fact, the guest list of our wedding was offered up as evidence that he worked with foreign spies. My friends and family were the spies. Anyway, after he was released, we were talking about the American Civil Rights movement and how much he admired it. Coming from a family of political activists and knowing my political proclivities, he naturally assumed my family must also have been involved in protests and demonstrations during that time, so he asked, "What did your parents do during the Civil Rights movement? What were their roles?" And I had no answer. My mom, who has never been political in her life, was one thing, but it was another thing altogether that my father, a man who talked of almost nothing but politics and history, should have had nothing to say on the subject. I wanted to explore that silence.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

Craft-wise, the hardest part of writing this book was finding the narrative connection between the two main events I was exploring, my father's suicide on a railroad track in small-town Florida and my relatives participating in the lynching of John Henry Williams in south Georgia. Once I started writing though, the details fell into place. Sometimes just the right piece of information would fall into my hands with such timeliness that I almost attributed it to something supernatural.

As for getting it published, for a year I sent it out to agents and independent publishers and did not even get a form letter "no," not one from over thirty queries sent out. It was very disheartening. I know my query letter was solid. I followed all the rules, queried people who had published books similar to mine. But it didn't matter. Then, finally I ran across April Gloaming, and they scooped it up.

I am told the market does not like memoir these days, but I think the market should like what I am doing, a white man looking at civil rights history as the perpetrator and addressing the crimes he is heir to. It's a reckoning.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

I used real names for all the dead. This seemed important. My father died in obscurity, a victim of a poisonous family dynamic that affected all of us in profound ways. We had always pretended everything was fine, and that pretense killed my dad. I wanted to name names.

For those living, I either got their permission or changed their names. My family aren't big readers and so running passages by them was not something that even crossed my mind. Plus, as the title makes clear, they have a tendency to want to edit out anything that isn't "nice," so most likely any changes they wanted would have killed the narrative. Only my Aunt Nancy loved to share the dirtiest secrets, and since she would tell the stock boy at Walmart or the drive-thru cashier at KFC as readily as she told me, I didn't feel it was all that secret anyway.

I did run all memories of key incidents by people involved again and again to make sure I had it right, or at least, that I had all the versions correct. That's part of the book's mantra; memories are not trustable. I also followed in part, Mary Karr who said in an interview that she had given her mother a heads-up that she was writing a memoir airing the family's dirty laundry. Did she mind being outed? “Hell, go for it,” her mother says. Karr writes, "She was an outlaw and didn't really give a rat's ass what the neighbors thought." Well, weren't we outlaws, too?

Craft-wise, the hardest part of writing this book was finding the narrative connection between the two main events I was exploring, my father's suicide on a railroad track in small-town Florida and my relatives participating in the lynching of John Henry Williams in south Georgia. Once I started writing though, the details fell into place. Sometimes just the right piece of information would fall into my hands with such timeliness that I almost attributed it to something supernatural.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

William Styron is one, as a white Southerner from a traditional Southern background who wrote unflinchingly about some of the most heinous historical crimes. Sophie's Choice combined research and story in a masterful way. Also, Joan Wickersham's The Suicide Index, about her own father's suicide was an inspiration.

In terms of structuring Gothic Southern memoirs, I read Jeanette Walls The Glass Castle and Mary Carr's The Liars' Club. I also learned a ton, mainly my limitations, from Ta-Nehisi Coates' Between the World and Me. But there was one author whose statement guided the whole thing. I kept his quote taped on a notecard over my desk, “The race question involves the saving of black America’s body and white America’s soul.” I was writing for the endangered souls, calling them out.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Be relentless and celebrate all successes, however small. When you finish a chapter have a beer or glass of wine or whatever constitutes a treat for you. When you finish a book, I don't care if only one person buys it, celebrate. You wrote a book! That's amazing. Now advocate for it as you would advocate for anything you love. And take nothing personally.

I had to beg my hometown library to carry my book, and it pissed me off, because better libraries jumped at it, but it was going in that library come hell or highwater. I come from a family of bizarre backwoods Southerners. I don't have time to be shy or embarrassed or proud. My advice is, don't fool with those emotions. Be practical.

And practically speaking, save money and set aside a budget for advertising, book prize applications, and reviews. All these things are important to getting your book out there, but they cost money. It was a two-year wait to see The Peril of Remembering Nice Things in print, and I set aside money every month in anticipation of these things. I am so glad I did.

What do you love about writing?

Moving the reader. I know I am supposed to write as if no one is watching, but I think you need to keep a reader in mind because you are trying to communicate something, and I just love it when someone tells me my story moved them or spoke to them, or they think a particular passage is lovely. It makes it all worth it. I feel like an actor on stage, in fact I have done some theater here and there. I know there is an audience watching, and if it comes, the applause at the end is just magic.

What frustrates you about writing?

Pretty much everything, but most of all when I find embarrassing typos after scouring it for errors four times and using Grammarly, spellcheck and everything else available. I am convinced my words change themselves after I close my laptop.

What about writing surprises you?

That it can get to a place beyond words sometimes.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

I have a toddler at home, so my routine is heavily proscribed these days. I generally get to work at 7:30. I'm a writing teacher at a private high school in Istanbul. Classes don't start till 8:00 so I try to write for those thirty minutes, Monday to Friday. I have to find a hiding place to do so or else students and fellow teachers harass me. In the old days, I would write at home on weekends from about 7:30 till 12:00 and then two or three nights a week from about 8 to 9. A routine is crucial.

I used real names for all the dead. This seemed important. My father died in obscurity, a victim of a poisonous family dynamic that affected all of us in profound ways. We had always pretended everything was fine, and that pretense killed my dad. I wanted to name names.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

Walks through the city are crucial to my process. So is long-distance running. I get these bursts of insight when I am out exercising like this. I have done some theater as well, mostly sketch comedy and improv. I also draw and love music. I love to sing, and I have learned Japanese drums and the ney, a Turkish wind instrument. I also love a good drunken bout of karaoke.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

Yes, but the aforementioned toddler makes getting much done on it difficult. It's a novel inspired by some of the research into family history I did while writing Peril.

Basically, my ancestors moved to south Georgia at a time when a lot of cultures and languages were crashing together, Muskogee Creek, Yuchi Indian, Gaelic, Spanish, West African and English. As a traveler and an amateur linguist, I am fascinated by languages. I want to explore this time when what is now a very monolithic culture was so diverse.

I discovered a murder in the family that was blamed on Creek Indians and happened around this time. It was never truly solved as the Creeks had long abandoned the region when the murder occurred. I want to explore that in fiction. Does that sound interesting? God, I hope so, because I'm writing it!

I really love reading these interviews. I want to read this book!

Loved this interview! Reckoning with our historical heritage is hard but necessary work…

Excited to read the book! I suggested it for my local library, hoping it comes through soon🤞