The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #21: Courtney Maum

"I have no problem putting my truth down on the page, but knowing that the real people in my book weren’t going to like that truth was extremely challenging."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

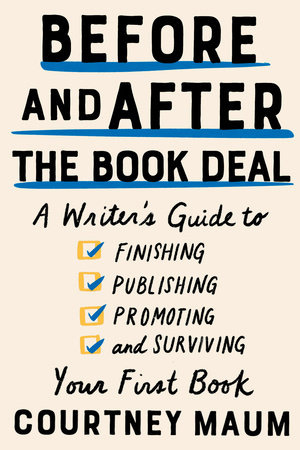

Here’s the twenty-first installment, featuring , author of five books, including the incredibly useful Before and After the Book Deal (plus her newsletter by the same name) and most recently, The Year of The Horses: A Memoir. -Sari Botton

Courtney Maum is the author of five books, including the groundbreaking publishing guide that Vanity Fair recently named one of the ten best books for writers, BEFORE AND AFTER THE BOOK DEAL and the memoir THE YEAR OF THE HORSES, chosen by The Today Show as the best read for mental health awareness. A writing coach, director of the writing workshop “Turning Points,” and educator, Courtney's mission is to help people hold on to the joy of art-making in a culture obsessed with turning artists into brands. Passionate about literary citizenship, Courtney sits on the advisory councils of The Authors Guild and The Rumpus and runs a bestselling Substack on publishing conundrums. You can sign up for her weekly newsletter and online masterclasses at CourtneyMaum.com

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m 45 years old. I have been writing since age 7. In second grade, a wonderful teacher named Mrs. Vicidomini taught us how to make our own books using wallpaper, cardboard and staples. We were supposed to bring in one finished book for our big project—I created five: The Magic Rosebush, The Winter Goblin and The Deer, The Last Lonely Pegasus and The Curious Little Horse, all of which were *heavily* inspired by The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. I even gave my books About the Author sections! From that moment on, I had the bug. Though I’ve had to earn a living using my writing skills in many ways, I never wanted to be anything other than a writer. It has always been my dream.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

My latest book is a memoir called The Year of the Horses. It came out with the independent publisher Tin House in 2022, on the very day that it was announced that Roe v. Wade would be repealed. I haven’t had the best luck with pub dates this decade. The book of mine before that came out during Covid, and the one before that came out just after Trump was elected. “Elected,” if you’ll allow.

What number book is this for you?

This memoir is my fifth book. I wrote two novels, a historical novel, and a book of nonfiction before “The Year of the Horses.”

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

This is a great question. All my projects are shape shifters. My memoir started off as a novel based on a video I’d seen of the dressage rider Andreas Helgstrand and his late mount Blue Hors Matine dancing to Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best” in a sport known as dressage. They were so in sync, so unified. That video made me realize how I wasn’t in my body and hadn’t been for a long time; that I wasn’t connecting with anything authentically; that I was super depressed. I started writing the book as a novel in 2016. It took me four more years to get the courage to write the truth; to write it as a memoir. Technically my memoir could be classified as a “hybrid memoir” because it integrates research, artwork, science and interviews to buttress the larger theme running through it about the patriarchy’s attempts to tame both women and horses, but I never refer to my book as a “hybrid memoir” because it’s a sterile sounding term, and memoir is so intimate.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

THE YEAR OF THE HORSES recounts the year I tried horseback riding as a last-ditch corrective against severe depression when everything else (medication, talk therapy, holistic treatments) had failed. Alternating timelines and braided with historical portraits of women and horses alongside history’s attempts to tame both parties, The Year of the Horses is a love letter to the power of animals—and humans—to heal the mind and the heart.

My memoir started off as a novel based on a video I’d seen of the dressage rider Andreas Helgstrand and his late mount Blue Hors Matine dancing to Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best” in a sport known as dressage. They were so in sync, so unified. That video made me realize how I wasn’t in my body and hadn’t been for a long time; that I wasn’t connecting with anything authentically; that I was super depressed.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I mentioned that watching a YouTube clip of Andreas Helgstrand was a catalyst—but it catalyzed a book other than my memoir. (I wrote a novel I shelved about a woman who’s jealous of the unique relationship that her champion dressage rider husband has with his horses, and one horse in particular, who ends up dying in a plane crash—along with the husband—en route to the Olympic Games. A real comedy!!)

What truly pushed my memoir into being was in 2017, I published an op-ed in the now defunct “Sporting” section of the New York Times about how learning to play the insanely dangerous sport of polo at nearly 40 years of age gave me an escape from my domestic life, and motherhood. So many people wrote me wonderful comments and letters about that essay. It really resonated with people—the way that fear can be empowering; how team sports offer new ways to make friends as an adult. I’d been thinking it was too privileged of a subject to explore, but the way people responded to that article made me think otherwise. Today, I’m proud of the chief message in my book, which is that women—especially mothers—need to have something in their adult lives that is exclusively for their own pleasure that feels a little magic. So much is asked of women in our culture, and honestly, in most cultures. If a woman isn’t fueled by something enchanting and a little selfish, the woman is going to break.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

To be honest, I find the writing of memoir easier than fiction. The great thing about memoir is that initially, your only task is to figure out how to present your memories into a satisfying narrative—you don’t have to make anything up. The “fiction” part of fiction is what challenges me—there are too many possible avenues to take, too many possible ways to tell one story. Publishing my memoir was also a joyful experience because I knew I wanted to partner with my Tin House editor Masie Cochran again (who published my historical novel, COSTALEGRE). Even though my memoir was so different from that novel, and even though Masie had some fear and negative feelings around horses, working with someone with whom I already had a literary love language made the pre-publication part of the journey so safe and nourishing. Once the memoir had a publication date though? That’s when things got hard. I have no problem putting my truth down on the page, but knowing that the real people in my book weren’t going to like that truth was extremely challenging.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

Risking hurting people’s feelings, igniting their wrath, getting something wrong factually, these were the hardest steps of the publication journey, and they’re the same reasons why so many people—understandably, but sadly—don’t put their truths down on the page. For starters, I gave the manuscript to my mother, father, stepmother and husband nine months before the book came out, and I gave them a very specific date by which any changes or requests needed to be communicated by. Everyone adhered to this deadline except for my father, who sent me his requests six days before the book published. For the other people in the book, I gave them the chapters that their sections appeared in so they could see the larger context around their contribution. Not everyone will—or should—share their manuscript with the people in it; that’s a decision that is personal and respective to the topic of the book, but I’d published a lot of personal essays and nonfiction prior to my memoir and had experience, historically, with things going poorly so I wanted to get out ahead of as much negativity as possible so I could be in a healthy place—emotionally—when it was time to promote the book.

Beyond sharing the full and partial manuscript with people, I changed the name of my husband and my daughter. Not really for privacy reasons, because a Google search will tell you what their names are, but rather because I couldn’t write bravely about them using their real names. Especially my daughter, because I gave her her name. I just had to break on through to the other side, really, where I wasn’t blocked with paranoia or guilt every time I saw my husband and daughter’s name in a Word document, and changing their names made that possible.

As for making the changes that my relatives requested—I did something kind of interesting: I incorporated what I got right and also what I didn’t. My mother in particular was helpful with some of the things I’d gotten factually wrong, or hadn’t had the full context around because I’d been a child. But I’d remembered things the way I’d remembered them for nearly 37 years, so what I did was leave my childhood memories intact and then later in the book, you’ll see me interviewing my parents, grappling with their versions of events. I did this with my husband’s feedback, also. There was one instance regarding the way both of us remembered a serious car crash we were in—I didn’t agree with his version, and he didn’t agree with mine, so I put both perspectives in the book with no pressure for the reader to decide which one is “right.”

It doesn’t matter who is right. What matters is that we don’t agree about what happened. To me that was the truest way to honor the act of memory itself, to show—to actually show—that no one will ever remember something the same way as someone else.

I’m proud of the chief message in my book, which is that women—especially mothers—need to have something in their adult lives that is exclusively for their own pleasure that feels a little magic. So much is asked of women in our culture, and honestly, in most cultures. If a woman isn’t fueled by something enchanting and a little selfish, the woman is going to break.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

I love this question. Truly, the thing that most inspired me in the writing and revising of THE YEAR OF THE HORSES was the Family Secrets podcast by Dani Shapiro. I was so inspired by the spiral shape of every episode. We know that there is a secret, because that’s the whole point of the show, but we don’t know when we’ll reach the telling of it. Dani, who is a gifted interviewer in addition to being a gifted writer, brings her guests in and out of their childhoods, a structural seesawing I wanted in my book. Her guests frequently admit to things they misunderstood as children, which gave me confidence to present memories through a few lenses in my book. The podcast gave me—and continues to gift me with—beautiful models for hard stories told well.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

This is going to sound like such a PSA for myself, but I am going to share it regardless because it contains what I think is the most straightforward and accessible way I know to improve one’s memoir writing, which involves incorporating a “double timeline.” I teach the double timeline in an online masterclass—if people would like to check it out, this link will give them a steep discount:

Big picture though, when it comes to writing memoir I think there are three important steps:

Write the first few drafts exclusively for yourself. Do not worry what other people will think or if you are betraying people or are going to get in “trouble.” Write it for yourself.

If you think you’ve got something publishable, the next step will be moving your memoir out of the “cathartic” stage of writing and bridging it toward the reader. This can mean and look like a lot of things—for me it entailed bringing in a secondary timeline about how (and how long) men had tried to keep women away from horses to move my book out of the “memories” space into a true memoir.

The last piece of advice must come after the first two steps are worked through. You’ll need a gameplan for letting your intimates know you’ve written about them and are intending to publish. Not letting them know might be your gameplan—that’s often the case for people writing about abusers or others who have caused grave harm, but in that case it would be wise to consult a lawyer (or talk things through with your publisher) to avoid legal repercussions.

What do you love about writing?

I love the possibility for connection with a reader, the possibility that you could move or excite or even help a stranger by what you put out into the world. And I love that writing allows us me to travel to so many imaginary places in my head on the cheap, that it allows me to use my imagination just as much as I did when I was a child. That is a real gift.

What frustrates you about writing?

How much time it takes, and how so much of my life—and American culture—is designed to take that time away from me. The pay structure of writing—when there is one—is becoming increasingly more challenging to navigate, and frankly quite unfair. I recently sat down with my spring royalty statements and saw that instead of earning $4 for each of my audiobooks sold, I was earning $1 because the publisher had decided to discount it. I wrote the book, I actually narrated the audiobook, and with this particular book I have single-handedly been doing the promotion for it without any assistance from this specific publisher for the last four years. And I’m getting well under the 25% royalty rate that was promised because they decided to discount the e-book?

There’s a reason authors aren’t educated on how to read their contracts and royalty statements—if we understood them better, we’d be in the streets raising bloody hell. With few exceptions, I have had wonderful relationships with my publishers but let’s be honest: with all the unpaid duties expected of authors today (we are event planners, social media managers, content creators, email list builders, copywriters, our own fact checkers and so forth) royalty rates need to be revisited across the board. I often dream of a socialist literary utopia where authors are given a baseline salary outside of book advances and/or royalties every year plus health insurance through the publisher their current book is with.

What about writing surprises you?

Oh, I think everything about it is surprising. That writers can use the exact same grammar rules and words and yet create something so wildly different from one another; that we can spend an immense amount of time alone only to create something that brings a lot of people together. The day that writing stops surprising me will be a dark, dark day indeed!

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

God, yes. Like every professional writer in America today, I wear a zillion hats. So I reserve Mondays and Tuesdays exclusively for my writing, and Thursday mornings for revision. If I can find other times in the week to work on my manuscript, wonderful, but at least I know I have three slots a week where nothing short of a wildfire can drag me from my work. I never work on weekends. At 45 years old with chronic insomnia that is only worsening as I age, I have to recharge or I’ll crack.

As for making the changes that my relatives requested—I did something kind of interesting: I incorporated what I got right and also what I didn’t. My mother in particular was helpful with some of the things I’d gotten factually wrong, or hadn’t had the full context around because I’d been a child. But I’d remembered things the way I’d remembered them for nearly 37 years, so what I did was leave my childhood memories intact and then later in the book, you’ll see me interviewing my parents, grappling with their versions of events.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

My husband is a filmmaker and we often write films together, or I collaborate and contribute in some other way. For example, I just translated his latest screenplay from French into English. Translation is a great love of mine—it’s what I majored in in college. A dream I have is to get my Spanish to a fluent level and to audit a Comparative Literature program at the University of Mexico. I’d love to work on translations when I’m older, most likely as a hobby. That would be a dream life. Or a dream retirement.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I have a novel that has been kicking my ass for two years and I’m finally in a place where I’m kicking it back. I hope to get the complete draft to my agent this summer, but that was my plan for the summer of 2023, and the draft wasn’t deemed ready. I hope I’m ready now! After that, I have a weird memoir about insomnia that I’d like to write as well as an essay collection. I’m really chomping at the bit to return to memoir writing. I feel vibrant and somehow purer when I’m writing nonfiction. Perhaps it could be seen as an egotistical pursuit, writing and thinking about yourself all day, but with fiction, I’m speaking with made-up people in my head, so which pursuit is kookier?

Great interview! Thanks so much for including the course on the double timeline.

Writers’ royalties DO need to change. Authors are tasked with much more promotion/admin than they used to be.

I also appreciated Courtney’s distinctions between writing fiction and writing nonfiction.