The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #116: Samina Ali

"It was important to me to capture as best I could how it feels to have brain damage: the disorientation and frustration and fear and anger and even arrogance."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

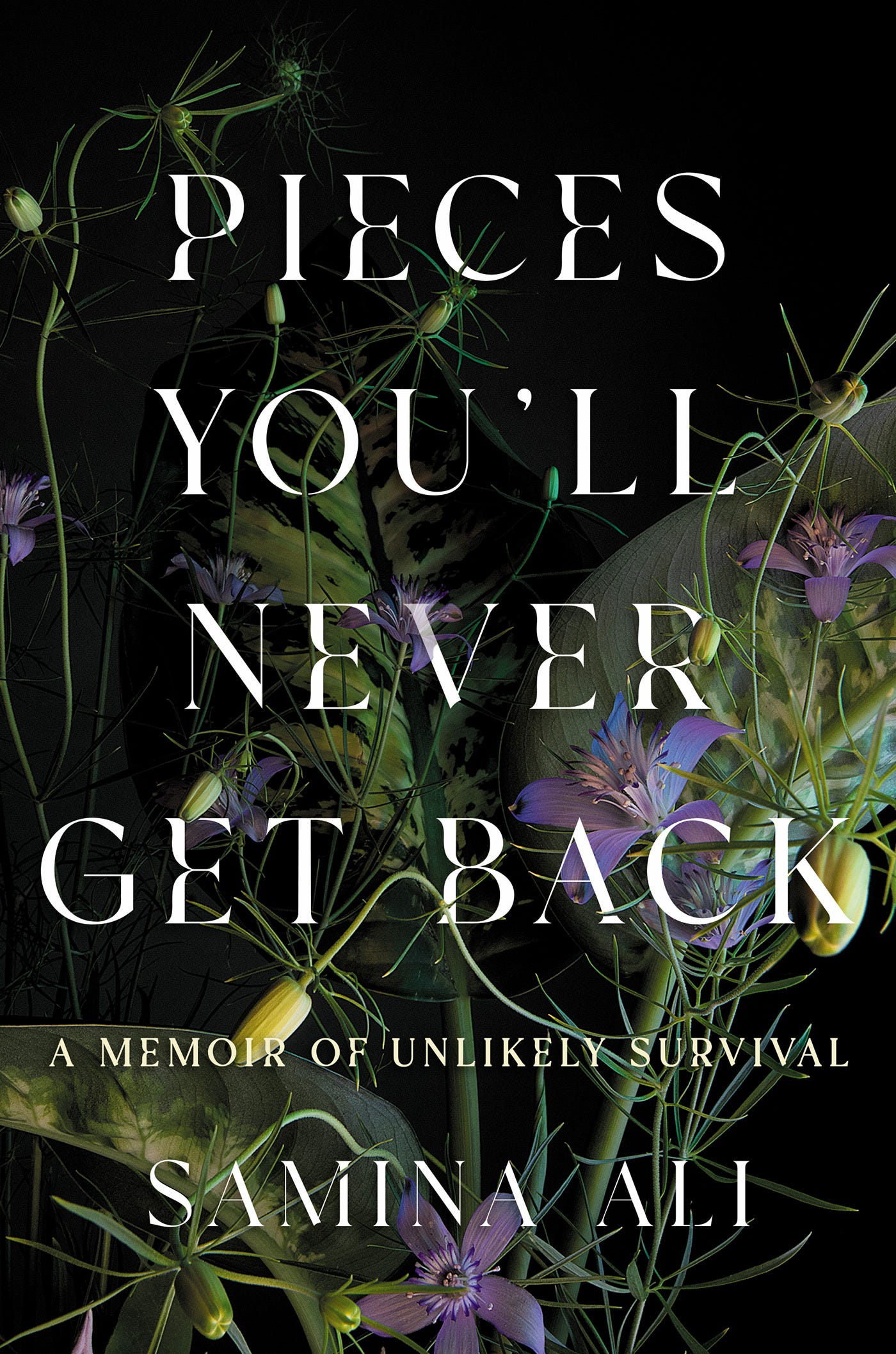

Here’s the 116th installment, featuring Samina Ali, author most recently of Pieces You’ll Never Get Back: A Memoir of Unlikely Survival. -Sari Botton

P.S. Check out all the interviews in The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire series.

Samina Ali is an award-winning author, curator, and popular speaker. Her debut novel, Madras on a Rainy Day won France’s prestigious Prix Premier Roman Etranger and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award. Samina’s viral TEDx talk “What Does the Qur’an Really Say About Muslim Women’s Hijab” and her global exhibition Muslima: Muslim Women’s Art and Voices express her passionate advocacy for contemporary women who are defining their own identities and shattering pervasive stereotypes. She was a featured speaker at the 2017 conference of the Nobel Women’s Initiative, an international advocacy organization founded by five women Peace Prize laureates. Samina's latest memoir, PIECES YOU'LL NEVER GET BACK, is about how her encounter with death from a nearly fatal illness fundamentally changed how she lives. Named a "Most Anticipated Book of 2025" by multiple outlets, including the San Francisco Chronicle, PIECES YOU’LL NEVER GET BACK is both deeply personal and an inspiring example of human determination and courage for anyone facing overwhelming odds. Find her on Instagram at @samina.ali.writer or www.saminaali.net

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’ve been writing for as long as I can remember. We emigrated from India to the US in the early 1970s, when I was about a year or two old (I don’t have a birth certificate). Every year, I traveled back and forth, spending months at a time in the twin cities of Hyderabad-Secunderabad and then the twin cities of Minneapolis St. Paul. I went to school in my birth town, learning Urdu and Arabic, and then I also went to school in a white suburb of Minneapolis, learning English and eventually French. It was a truly bi-cultural, bi-lingual upbringing—and also a bifurcated upbringing. Writing in English and Urdu, the script moving left to right and then right to left, was my way of bringing my two worlds together.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Pieces You’ll Never Get Back was published March 4, 2025.

What number book is this for you?

My first book was a novel, Madras on Rainy Days. It was released twenty years ago! I wrote that novel through brain damage. The process was so excruciating that, although I’d written since I was a child and, although writing had always been sacred to me, I couldn’t get myself to return to the desk. Every time I thought about sitting down to write, the image of me sitting at my computer writing my novel would rise up.

Back then, in the early stages of trying to write, in the late stages of massive brain trauma, any attempt to write would bring on a massive headache. After only five minutes, I’d have to allow my body to simply fall from the chair to the ground, where I would lie curled up in a fetal position against the pain. The English language had left me because of the extreme Aphasia I was dealing with, so words I thought were not the words I would end up typing on the page. Often, I wrote nothing more than gibberish—and would not even realize it was gibberish until much later, because it would make sense in the moment of writing to my broken brain. Those troubling memories stopped me from writing for many years. And when I did return, it was to confront those very memories.

Pieces You’ll Never Get Back is a searing look at how, at 29, as a young writer working on my first novel, I nearly died giving birth to my son. I went into the hospital to have a baby. I came out brain damaged. Miraculously, I survived the unchecked eclampsia that had endangered my pregnancy, instead sustaining major brain injury and falling into a coma as I gave birth. When I woke up, only my deepest memories were intact. My husband was a stranger to me, I didn’t remember having a baby, and any language other than my native Urdu was foreign. Medical consensus was I would never recover—much less write—again.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

My current book, Pieces You’ll Never Get Back, is a searing look at how, at 29, as a young writer working on my first novel, I nearly died giving birth to my son. I went into the hospital to have a baby. I came out brain damaged. Miraculously, I survived the unchecked eclampsia that had endangered my pregnancy, instead sustaining major brain injury and falling into a coma as I gave birth. When I woke up, only my deepest memories were intact. My husband was a stranger to me, I didn’t remember having a baby, and any language other than my native Urdu was foreign. Medical consensus was I would never recover—much less write—again. I don’t consider it a medical memoir because I keep medical jargon to a minimum. Rather, the central message is about resilience and hope.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Although the central story is about my recovery from the complete collapse of my body (multiple organ failure, brain damage, heart damage, vasculature damage, etc.), my ultimate purpose was to express how my encounter with death fundamentally changed how I live. My brain damage showed me how so much of our identity—our ideas about who we are and where we belong in the world—is nothing more than the wiring in our brains. And that wiring in our brain is the result of what we’ve been taught growing up by our parents, teachers, the wider communities we live in, as well by as our past experiences—and, importantly, the meaning our brain then assigns to those past experiences. One of the most unfortunate things all of us have been taught is that the differences in our skin color, economic standing, cultural background, gender, or our faith make some of us inferior to others. Our differences have long been weaponized to sow divisions. An experience with death shatters these demeaning notions, renders them meaningless. We are matter and energy, all of us, united as one humanity at the most intrinsic levels.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

The first person to tell me to write this memoir happened to be my neurologist. At our final meeting three-and-a-half years after my son’s delivery, we discussed what might have contributed to my recovery. When I told him that I’d written a novel, he was struck with the idea that I might write about my recovery. He said that doctors could explain what’s happening inside a damaged brain only from the outside, based on medical books and practical experience working with patients, but that I could write about it from the inside. He imagined it might be useful. It took me many years to feel like I could write about my journey. When I finally sat down, I used his comments as a guide. While it’s true that every patient with brain damage recovers differently, it was important to me to capture as best I could how it feels to have brain damage: the disorientation and frustration and fear and anger and even arrogance. It’s an isolating, lonely experience.

When I lost my ability to speak and write, I’d also lost my higher mental processes to think, to imagine, to create —those abilities that are intrinsically human, separating us from animals. I felt lost then, unmoored. It was one of the darkest periods of my life. While I still experience moments of aphasia when writing and speaking, losing my ability to speak properly in English taught me the importance of words. Think about how magical language truly is. We are able to make sounds with our mouths and tongue that have meaning, not only to us but to those around us. Letters are symbols that, without our mutual agreement, would have no meaning or purpose. How amazing! Think how lonely and myopic our experience of this world would be if we were unable to communicate with one another, to make connections—not just by speaking, but by putting words down. That’s where I lived during one of the darkest periods of my life.

When I became pregnant with my daughter, I knew there was a chance I wouldn’t survive the delivery. It suddenly felt urgent to write the story, to leave a legacy for my son, who was almost 9 years old at the time. That story was never formal. I handwrote my memories in a journal. After my daughter was born, I put the writing aside because I wanted to experience motherhood, something I hadn’t the first time around. But every moment I spent with her was a reminder of those moments I’d lost with my son. Like that, the trauma of his delivery continued to impact me in different forms throughout my life.

We believe healing should end at a certain point, but we carry our losses and our pain and our struggles. About six years ago, when I finally got serious about writing the memoir, I was astonished to discover that eclampsia was still the most common complication of pregnancy. We still don’t know what causes it. Women are still dying from it. The U.S. is the only developed nation where the maternal mortality rates are rising. How could this be possible, fifteen to twenty years after I delivered? With a heavy heart, I have to admit that my story is still timely.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

I not only was trained as a fiction writer, but I also teach fiction writing! That made the process of writing a memoir incredibly difficult. All too often, I found myself turning to fictional craft, creating scenes and dialogue and trying to show what happened rather than just coming out and telling it. It was actually the biggest hurdle I had to overcome this time around. Draft after draft after draft, I had to fight against my own impulse to craft scenes. Writing memoir is an entirely different skill set, and I had to teach myself that skill set while writing the memoir. It wasn’t easy.

I went with Catapult for many reasons: it’s an independent press; my entire team (including my two uber agents at Janklow & Nesbit and everyone at Catapult) is women; and, most importantly, I chose Catapult because I was so impressed with how smart and talented my editor, Kendall Storey, is. She impressed me during our first discussion of the memoir with her vision and then, when she was editing my manuscript, she just kept on impressing me with her insights and feedback. I’m indebted to her for helping me to shape this book. My publicist, Megan Fishmann, is a dream come true, a true PR sorceress. To say I’m grateful for this power-team is an understatement.

Although the central story is about my recovery from the complete collapse of my body (multiple organ failure, brain damage, heart damage, vasculature damage, etc.), my ultimate purpose was to express how my encounter with death fundamentally changed how I live. My brain damage showed me how so much of our identity—our ideas about who we are and where we belong in the world—is nothing more than the wiring in our brains. And that wiring in our brain is the result of what we’ve been taught growing up by our parents, teachers, the wider communities we live in, as well by as our past experiences—and, importantly, the meaning our brain then assigns to those past experiences.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

I only changed one name: the name of my son’s father. I did that because we’ve been divorced for over twenty years and we each have married again and have children. I respect his privacy. Others in the book all bear their real names.

Writing a memoir is different than writing a news story. I’m not a journalist. I’m not trying to get down facts. I’m trying to hold multiple truths in my memoir—and those multiple truths lead to some semblance of fact. So, I didn’t feel I needed to run passages by anyone. In fact, my son’s father had stopped his subscription to The Washington Post during the 2024 presidential elections. Recently, however, Pieces You’ll Never Get Back was featured prominently in the book section. He read the profile and was deeply moved—so much so that he resubscribed to the Post and thanked me for truthfully representing the important part he played in my delivery and recovery. I’ll be giving him a copy of the memoir.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

I read memoirs. Helen MacDonald’s H is for Hawk. Jill Bolte Taylor’s My Stroke of Insight. Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air. And, Brain on Fire by Susannah Cahalan. I wanted to read about others’ accounts about trauma, healing, forgiveness, spirituality, and hope.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Fear is a natural part of writing. I think every writer is afraid on some level of the empty page, of starting a new project. I don’t think it helps to try to ignore fear. Nor can we be ashamed of being afraid. We have to embrace our fears, see what those fears teach us about who we are and, most importantly, listen to what those fears tell us about what we want for ourselves.

What do you love about writing?

Writing is a space where anything is possible. It’s MAGIC.

What frustrates you about writing?

Since I was struggling with English when writing Madras on Rainy Days, I heard the novel in my head in Urdu. All the characters spoke in Urdu. The narrator spoke in Urdu. To write my novel, I had to first translate the Urdu to English and then type the English onto the page accurately through the aphasia.

Part of my journey to re-master English meant that I had to live inside English, speaking it to others, speaking it to my son, and speaking it to myself. Over those years, that meant that I gradually stopped thinking in Urdu and started thinking in English. When I wrote Pieces You’ll Never Get Back, I heard the words in English and, for the most part, I accurately typed the words in English through whatever remnants of aphasia I still experience.

Who I am in Urdu is different than who I am in English, so while I’m grateful that my English has returned, I’m also frustrated and sad about what I’ve lost in the process. Writing is a reminder of both my losses and my gains.

What about writing surprises you?

Novels are different than memoirs. You can plot a novel. In the early stages, you can have a narrative design in mind and stick fairly close to it as you write. With memoirs, the structure and narrative design often comes at the end, after you’ve written the story once or twice or even multiple times. I often joke that Pieces You’ll Never Get Back was as traumatic to write as my son was to deliver. That’s because it was an emotional journey and because, as I spoke to earlier, of my own struggles over learning how to write a memoir, and also because I wrestled with the structure for years.

I knew this story couldn’t be told as a straight narrative, but my brain was stuck in “novel-mode,” and I couldn’t think outside that. When the breakthrough finally came and it struck me that I had to break open the book so that the chapters mirrored the different islands of my broken brain, coursing back and forth in time, presented as long and short, as though the narrative itself was shattered, I felt such overwhelming joy. All the stagnant energy I’d accumulated over the years of struggling with the structure suddenly had an outlet and came gushing out. I sat down and rewrote the entire book in six weeks. So, anyone writing a memoir: please be patient. Know that the form will emerge from the story, and not the other way around.

While I still experience moments of aphasia when writing and speaking, losing my ability to speak properly in English taught me the importance of words. Think about how magical language truly is. We are able to make sounds with our mouths and tongue that have meaning, not only to us but to those around us. Letters are symbols that, without our mutual agreement, would have no meaning or purpose. How amazing! Think how lonely and myopic our experience of this world would be if we were unable to communicate with one another, to make connections—not just by speaking, but by putting words down. That’s where I lived during one of the darkest periods of my life.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

Writing a book demands a daily writing routine. It’s not just about training writing muscles to string words and sentences together with more ease, it’s about remaining inside the world of the book. When I’m in the midst of writing, I’m most terrified by school holidays: summer, winter, spring break!! My son is now grown and independent, but I have a daughter at home, and any break from school means an abrupt, jolting stop to work. It’s the thing I dread the most.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I think of writing as a long, lonely walk through the desert. You never know if you’re headed in the right direction. You don’t know if you’ll make it out. Then, suddenly, you reach an oasis. That oasis is necessary. The oasis reinvigorates you to continue the long, lonely walk. For me, an oasis means going to art exhibits and traveling to foreign countries and even teaching other aspiring writers. Because my two children are nearly a decade apart in age, when my son went off to college, my daughter was still in elementary school. This means I’ve been nonstop parenting for what feels like 80 years. So, an oasis for me also means I’m lucky to get the chance to play … and play a lot with my kids.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I’m in the early stages of working on a fantasy novel. It’s so exciting because it means I get to play on the page!

What an incredible story of resilience and recovery. Ms Ali mentions this:

>>I went to school in my birth town, learning Urdu and Arabic, and then I also went to school in a white suburb of Minneapolis, learning English and eventually French. It was a truly bi-cultural, bi-lingual upbringing—and also a bifurcated upbringing. Writing in English and Urdu, the script moving left to right and then right to left, was my way of bringing my two worlds together.

I'm wondering if her amazing brain was able to recover -- in ways doctors don't fully understand -- because it was so adaptive before the injury.

Loved the Q&A with Samina. Raw and beautiful, the part around our differences weaponized to sow divisions amongst is so timely. Not in the Q&A of course, but during the interviews, the way you interject your experiences and make it sort of like a seamless conversation with the author being interviewed makes for a very satisfying listen/watch (and a useful!)