The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #53: Charlotte Shane

"The difficulty these questions point to—discrepancy in experience, discrepancy in comfort with disclosure–can’t be eliminated in life or in art."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

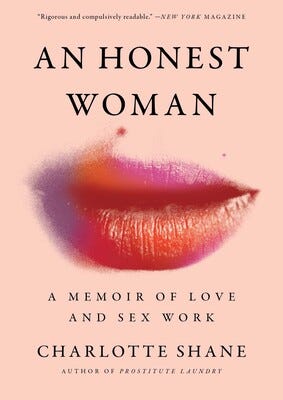

Here’s the 53rd installment, featuring , author, most recently of An Honest Woman: A Memoir of Love and Sex Work. -Sari Botton

Charlotte is an essayist and publisher whose books include Prostitute Laundry and N.B. She co-hosts a podcast called Reading Writers with critic Jo Livingstone, and writes a free newsletter/blog called Meant For You.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m 42, and I’ve been writing since I had a decent grasp on language—pre-literacy, by dictating stories to my accommodating mother.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

An Honest Woman: A Memoir of Love and Sex Work, which was released in August of this year (2024).

What number book is this for you?

My third.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

“Creative nonfiction” is appealing, but I’ve made my peace with memoir, which is how the publisher wanted it identified in the subtitle. I think of memoir as being an autobiography that follows the author from childhood on, and this book is more selective and thematic than that. But the distinction is just for marketing, I think, as opposed to a reflection of how I conceived of what I was doing/what I have done.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

I use my past, mainly my time as a sex worker, to consider the dynamic between men and women. It’s a book about heterosexuality but also women’s non-romantic and non-sexual relationships with men, because heteronormativity and gender roles and money and misogyny infect everything. Ultimately, because I have faith in our propensity and desire to connect with one another, the book is hopeful about the potential for true intimacy and love despite the many obstacles.

I self-published my first two books with the assistance of a Kickstarter campaign, and around that time, agents started approaching me. An Honest Woman is the first book of mine that went the traditional route (agent to proposal to purchase and release by a mainstream publisher.) Before it sold, I hosted a monthly reading series in New York that lasted for two years, and I felt very much in the mix as a writer without having the endorsement of the so-called Big Five. But getting involved with them also seemed like it should be the next step.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I studied writing and literature in undergrad, then got a Masters degree in poetry, which was of no use in terms of getting me “in the door” someplace, but it supported my writing practice and made a writing life seem attainable. After school, I freelanced, and in my twenties I had a well-read blog, then later a newsletter. I built my reputation that way, and a lot of my readers were/are other writers, which has been wonderful and extremely advantageous.

I self-published my first two books with the assistance of a Kickstarter campaign, and around that time, agents started approaching me. An Honest Woman is the first book of mine that went the traditional route (agent to proposal to purchase and release by a mainstream publisher.) Before it sold, I hosted a monthly reading series in New York that lasted for two years, and I felt very much in the mix as a writer without having the endorsement of the so-called Big Five. But getting involved with them also seemed like it should be the next step.

In my twenties, my boyfriend gave me Ariel Gore’s How To Become a Famous Writer Before You’re Dead and in retrospect, I see that it changed my life. As a creator, you can do a lot of things for yourself, especially right now. If someone else won’t do something for you, that doesn’t mean it can’t get done. You don’t have to wait for permission. You might even discover that you like your own way of doing it more.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

My third book’s proposal sold to an editor who was interested in my first book, Prostitute Laundry, so that part felt easy (to me) though my agent indicated the contract required a lot of negotiation, none of which I was privy to. My enthusiasm for the book as it was described in the proposal quickly waned and then died out entirely, so writing the manuscript was challenging for a while—as in, it was not happening at all! I just couldn’t find a way into the subject matter, and I hope to never sell a book on proposal again. But once I figured out a new angle, composition wasn’t so bad. I think it took me about a year, maybe a year and a half. And though my acquiring editor left the publisher in the years between my selling it and delivering it, I ended up working with a wonderful editor, so it was a serendipitous twist of fate.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

I offered to let my husband read the book in advance, or at least the final chapter which is about him, and he didn’t want to. There is no one else in the book who I ran the manuscript by before publication. I changed most names as a basic courtesy, but probably everyone mentioned in the book can easily recognize themselves and some other parties. Those readers must feel (correctly!) that their portrayals are incomplete, if not at odds with their own memories. I tried to include only what was relevant and I certainly didn’t write with an intention to hurt those I wrote about.

The difficulty these questions point to—discrepancy in experience, discrepancy in comfort with disclosure–can’t be eliminated in life or in art. That's no excuse for carelessness, but I think recognition of that much should be the starting point for all personal writing.

I use my past, mainly my time as a sex worker, to consider the dynamic between men and women. It’s a book about heterosexuality but also women’s non-romantic and non-sexual relationships with men, because heteronormativity and gender roles and money and misogyny infect everything. Ultimately, because I have faith in our propensity and desire to connect with one another, the book is hopeful about the potential for true intimacy and love despite the many obstacles.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

Rachel Cusk’s Aftermath was in my mind as well as The Incest Diary, which is anonymously authored, because they’re extremely powerful short books. The writing in each is excellent but I wasn’t modeling my organization or tone on theirs, at least not consciously. (I haven’t read either of them in years.) It was more like I aspired to that quality of intensity and impact.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

This is a really hard question. Mainstream publishing is intimidating, and frustrating. Maybe I should take this opportunity to confirm that the system is not a meritocracy, that luck, prejudices, and capitalist cynicism are the dominant deciding factors. That might not seem reassuring at first, but my point is that if you’re having difficulty finding an agent or publisher, it isn’t proof that your writing is bad. Perhaps your writing does need improvement, or the manuscript isn’t working. But your book could be very good, and the issue is that it’s difficult to sell.

The industry’s fixation on follower counts and public presence is exhausting and demoralizing. But if you’re able to find a readership on any platform, in any way—through fan fiction, a newsletter, a writing group or workshop—it will give you valuable experience. The media industry is in freefall and social media’s power is waning by the hour, so it’s a very difficult time to break in. But not impossible. The Freelance Solidarity Project’s resources guide might have tools you find helpful even if you don’t want to freelance.

It might be useful to ask yourself why you want to be published by someone other than yourself: is it for validation, or money? Or because you don’t know how to reach an audience? You might not want to take on the labor of publishing and distributing, which is entirely understandable. But there may be a point at which that’s your best option.

What do you love about writing?

I’m most myself while I’m doing it, so it’s not a behavior I can abandon. Because it’s instinctive and imperative for me, loving it feels beside the point. Yet writing can be a route to the fulfillment people crave across contexts and careers: to be respected by those you respect, to have fun, to create, to connect, to learn. Often, the absorption of the moment gives way to joy.

What frustrates you about writing?

The longer you write, I think, the more inevitable your confrontation with the limitations of language—not just your language, but the whole enterprise. Of course my failures and struggles are at the forefront for me, but I worry I’m asking something of my writing or imagining my writing can accomplish something that no writing can achieve. This is an existential inquiry that goes well beyond style or craft, into larger questions about human behavior and communication, our responsibility to one another and so on.

There’s an essay by Judith Thurman in which she speculates that while Neanderthals were going extinct, they began to imitate the artistic expression of the Homo sapiens who supplanted them. (“The pathos of their workmanship—the attempt to copy something novel and marvelous by the dimming light of their existence—nearly makes you weep.”) That’s how I feel sometimes when I look at the gap between the finest writing and my own. But it’s either that or don't make the effort at all.

What about writing surprises you?

That you actually have to do it. I’m somehow always trying to find a way of having written without doing any writing.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

Not really, but that’s to my detriment. For years I’ve wanted to be someone who can establish a routine, but I guess I haven’t wanted it enough to do it. I used to write mostly at night, probably between 11pm and 3am. Now I mostly write during daylight hours. When I freelanced, deadlines deranged any nascent pattern.

In my twenties, my boyfriend gave me Ariel Gore’s How To Become a Famous Writer Before You’re Dead and in retrospect, I see that it changed my life. As a creator, you can do a lot of things for yourself, especially right now. If someone else won’t do something for you, that doesn’t mean it can’t get done. You don’t have to wait for permission. You might even discover that you like your own way of doing it more.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

My writing suffers when I don’t read, though sometimes I let reading substitute for writing and that’s also bad. I recently went on a trip with two close friends where we wrote together (meaning separately in the same space) and shared some of our writing on the last night. I left so inspired that it felt illegal, like I’d taken a Class A drug. For everything, friendship is indispensable.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I’ve started two novels, one of which is substantially written and the other of which is still at its beginning. Lately I’ve been concentrating on a short story unrelated to either. And there’s a project my husband and I have planned to do with our press for years, about grief, but I haven’t finished it because every time I think about it intensely, I cry! A lot! But I hope we can complete it and release it next year.

I loved this interview! I love so much of Shane’s criticism and am hoping to read An Honest Woman soon—this was such a great conversation and so lovely to read about her writing process, the arc of her career, and how she thinks about disclosure, publicity and ambition.

Her note on the ethics of personal narrative/memoir was particularly useful and insightful: “Probably everyone mentioned in the book can easily recognize themselves and some other parties. Those readers must feel (correctly!) that their portrayals are incomplete…The difficulty these questions point to—discrepancy in experience, discrepancy in comfort with disclosure–can’t be eliminated in life or in art. That's no excuse for carelessness, but I think recognition of that much should be the starting point for all personal writing.”