The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #103: Joyce Wadler

"I’m not enough of a masochist to run my work past other people. I try not to be a jerk when I write about them...But if you write to please other people, you’re finished as a writer."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

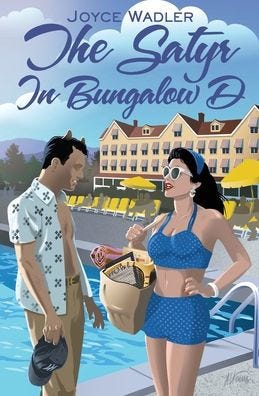

Here’s the 103rd installment, featuring , author most recently of the autobiographical novel, The Satyr in Bungalow D. -Sari Botton

P.S. Check out all the interviews in The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire series.

Joyce Wadler is an award-winning York City humorist and journalist who created and wrote the “I Was Misinformed” humor column for The New York Times, where she was a reporter for 15 years. She now writes a humor column on Substack.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m 77 and have been writing since I was 6 or 7. Although the earliest stuff needed work.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

The Satyr in Bungalow D. It was published May 1. You can order it here. Or here if you’re boycotting Amazon. Or go to your neighborhood bookstore. There are still a half-dozen left in this country.

What number book is this for you?

Three.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

Satyr is a memoir masquerading as fiction—really masquerading. It’s told from the point of view of a lovelorn satyr who lives on the outskirts of a ramshackle Borscht Belt hotel. But it was my family’s hotel, it includes members of my family, and that satyr, Danny, in a lot of ways, is me. He’s the equivalent of an 18-year-old guy, he sleeps in a cave, he’s got horns and hooves, but the more I wrote him, the more I could see he was me: He’s a songwriter—which is just another form of being a writer—and he worries that his work is no good. He’s obsessed with falling in love. He’s convinced that if he can write a song that’s beautiful enough, it will solve all his problems.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

“The resorts in the Catskill Mountains are struggling in 1963, but the town of Fleischmanns has a secret that keeps the tourists coming back: A hidden colony of satyrs. Strikingly good-looking and differing in appearance from humans only because of their short horns and delicate hooves, it is easy for satyrs to pass. In the summer, when New York City ladies take solitary and hopeful walks up the mountain paths, they frequently do. That great-looking guy who gave a New York City college girl the best sex of her life behind the tennis courts and refused to take off his hat? Most likely a satyr.”

That’s from the book jacket. I’ve done so many pitches, it’s seared onto my brain.

Satyr is a memoir masquerading as fiction—really masquerading. It’s told from the point of view of a lovelorn satyr who lives on the outskirts of a ramshackle Borscht Belt hotel. But it was my family’s hotel, it includes members of my family, and that satyr, Danny, in a lot of ways, is me. He’s the equivalent of an 18-year-old guy, he sleeps in a cave, he’s got horns and hooves, but the more I wrote him, the more I could see he was me: He’s a songwriter—which is just another form of being a writer—and he worries that his work is no good.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I’d had the idea of this book for decades. When my agent was pitching this book, an editor said, “Oh, yeah, Joyce told me about that years ago.” I couldn’t even remember meeting the guy.

But I think the idea of the book began with something I saw at my family’s boarding house, in the Catskills: A few middle-aged guys setting up a card table under a tree and putting a maple leaf under the bridge of their glasses to keep their noses from getting sunburned. For some reason, this struck me as hilarious. I was 6 or 7 at the time. Why this image struck me, I don’t know. In my family, we referred to guys this age as “old goats. They also hung out around the pool, again playing cards but always with an eye on the women.

Satyrs with an eye for the ladies sitting around a pool was the starting point of the novel. I’m not sure how it made the leap from men to satyrs, but it immediately did—satyrs who disguised what they were by wearing hats and sandals and just radiated sexuality.

And just as fast, my main character, Danny, appeared. He was the son of one of satyrs at the hotel pool, but unlike the old goats, he did not want to make love to every woman he met. He wanted the one great love he had read about in The Great Gatsby, which he had found on the hotel grounds. He wasn’t able to finish it because the last chapters were ruined in a June rainstorm, but Danny is convinced a love as great as Gatsby’s can end only one way: with Gatsby and the woman he loves together for the rest of their lives.

It doesn’t surprise me that my mind served up satyrs. When it comes to men, I have a type: Warm, beefy, earthy—the kind that would do you up against a tree and who cares if the Boy Scouts see you? In my bedroom I have an etching of a satyr and a naked woman by French artist Almery Lobel-Riche that I picked up at a flea market in Paris. He’s looking down appreciatively at a woman, she’s stretched out on his lap in naked bliss. And what a set of horns on the guy.

And remember, I grew up in a resort community. In summer, the New York City tourists came up but, more importantly, the smart, funny, sharp New York City boys from CCNY and the Bronx School of Science came up to be waiters and busboys. And there were women who were hotel guests, whose husbands stayed in the city during the week, working—weekday widows, who the waiters were ordered to be nice to. That’s nice with no pants. The towns were pulsating with sexual possibility. They were vibrating. I thought the greatest thing in the world would be to make it with someone who loved you, in the summer grass. I guess I still do.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

I was working as a reporter, I didn’t have the time to write a book. And I couldn’t get my arms around it, I couldn’t find the tone for Danny’s story. Should I tell it first person or third person? What age should he be when he’s telling his story?

But it kept nagging at me. It was a story that wanted to be told. I felt—this will sounds nuts—I wouldn’t be able to rest, to shut off the voice of it in my head, until I got it down.

Then COVID hit. I had left the Times, I wasn’t writing, so there was nothing to distract me. The idea of this book—which like I said never went away—kept getting stronger. I struggled for a few days trying to figure out how to come at it and then the lead just appeared:

My grandfather came to America in the mind of the woman he loved, an Italian opera singer, and emerged, blinking, into the sunlight of a tiny resort town called Fleischmanns in the Catskill Mountains.

Entering the mind of a sleeping woman is not unusual if you’re a satyr, one slips in and out all the time. What is unusual is that my grandfather traveled over the sea. Satyrs shun and fear large bodies of water. My grandfather insisted it happened after one last tryst before his lover was to leave for a grand tour; that he fell asleep and when he awoke, the ship had sailed. What I believe is she made him so love-crazy, he could not bear to leave.

Getting the book published the traditional way was impossible. I think about thirty publishers turned it down. There was a lot of, “We haven’t had a lot of luck with humor.” And, “Satyrs? I don’t know, #MeToo…”

Finally. I said to my agent, “Screw it, I’ll do it myself—and I’ll make it a beautiful book.” I hired great people; a cover artist whose work I loved, professional editors, a book formatter; I did everything; contacting bookstores, trying to get the book to reviewers, stumbling around Goodreads.

Those two or three years of rejection I’d had turned out to be very useful; I got good input from friends who are writers; even editors who rejected the book had things to say that were helpful. I was constantly rewriting. My copyeditor, Nancy Wartik, who had worked at the Times, said, “You’ve got a book about a guy trying to write songs, but you’re not showing him working.” She was right. In musical comedy, you write a song when the emotions are too strong for words and that’s what I did. I showed a song coming to Danny and him rejecting it because he thinks the words are stupid. But the words keep coming back—they’re his words, his feelings—and at the end he has the confidence to sing them to an audience. The minute I did that, the book clicked. I knew it was where it needed to be. It had the heart it had been missing. With Danny’s song, it was done.

The downside of this whole self-publishing business is, it left me no time to work on anything but the book. I had to put my Substack column on hold and it cost a fortune. But the book is now exactly the way I want it.

Getting the book published the traditional way was impossible. Finally. I said to my agent, “Screw it, I’ll do it myself—and I’ll make it a beautiful book.” I think about thirty publishers turned it down. There was a lot of, “We haven’t had a lot of luck with humor.” Those two or three years of rejection I’d had turned out to be very useful; I got good input from friends who are writers; even editors who rejected the book had things to say that were helpful.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

I’m not enough of a masochist to run my work past other people. I try not to be a jerk when I write about them; I try to respect what they’re sensitive about; but if you write to please other people, you’re finished as a writer.

Also, most of this book takes place in the ‘60s, so the real people in the book—my grandmother, father, and uncle—are gone. I used their first names, but I used my grandmother’s maiden name instead of family.

I was a little concerned because I have cousins in the town I wrote about and I didn’t want the book to embarrass them—these satyrs do have a tremendous amount of sex. But it’s not like it’s real; they’re satyrs. So, I think I will be okay.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

A few drafts in, somebody mentioned Alice Hoffman, who does a lot of magic realism. She’s a beautiful writer, but I picked up one of her books and there was a character, possibly a witch, who could ripen a piece of fruit by just touching it. I had already written about Bavarian nymphs who were so ripe they could do the same and I thought, “Time to stop reading Alice Hoffman.”

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Just write it. Fear is the enemy, fear freezes you up and keeps you from writing. Once you’ve got something on the page, even if it’s not what you hoped, you can rewrite it. But if you don’t have anything on the page, you have nothing to make better.

What do you love about writing?

That’s a question which suggests it is optional, which for me it is not. When I don’t write, I get depressed. When I write something I like, it’s the best feeling in the world. Maybe love in the grass is better, but then you’ve got those mosquitos.

What frustrates you about writing?

When I’m in a dry spell. When I feel like I’ll never have another idea.

What about writing surprises you?

I always get another idea.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

For a few years, when I woke up, I’d stay in bed, turn off the WiFi and write whatever came into my head. A lot of humor columns came out of that. Then I got involved in self-publishing and it stopped. I woke up petrified about loading the manuscript into Ingram Spark. But now that this damn book is launched, I’m going back.

The downside of this whole self-publishing business is, it left me no time to work on anything but the book. I had to put my Substack column on hold and it cost a fortune. But the book is now exactly the way I want it.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I take a lot of time choosing pastry.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

No. This was the book I wanted to write and I wrote it. Now, I’m gong back to Substack.

I've been trying, and failing, to land an agent for an illustrated memoir I've completed. Despite the encouragement I've received, I've also had zero luck moving beyond "Well, we've never seen anything quite like this before, and we're not sure we ever want to again." And yet the excerpts I run from it are my most popular posts at petermoore.substack.com. Not that that proves anything, but still. Sometimes the work needs to be what it is, and nothing else, even when current book-sales group-think says, "nah."

So many great nuggets in here, including that nagging feeling of a story inside us that needs to be told. Also, love the attitude about accepting feedback even when it’s a part of rejection. We can always learn from feedback if we are willing to hear it. Nice interview!