The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #114: Cara Gormally

"This is not just my story—it is the story of many people who’ve survived sexual assault. It is also the story of many queer people and the abandonment that they face from their families."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

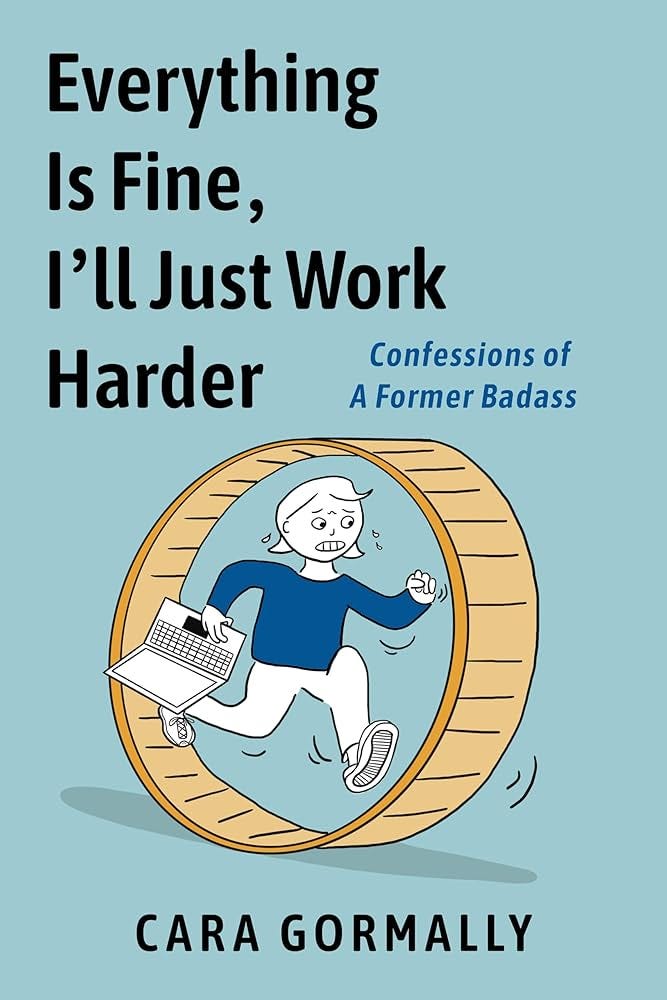

Here’s the 114th installment, featuring , author of Everything is Fine, I’ll Just Work Harder: Confessions of a Former Badass. -Sari Botton

P.S. Check out all the interviews in The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire series.

Cara Gormally is a cartoonist, researcher, and professor. Cara’s narrative nonfiction comics remix autobiographical stories with research about socio-scientific issues to make science relatable. Their comics have appeared in the Washington Post, Mutha Magazine, Spiralbound, and other places, including their substack newsletter, Soft Things. Their debut graphic memoir, Everything is Fine, I’ll Just Work Harder, a story about an unexpected healing journey to come home to themself, is was published in April 2025 by Street Noise Books. Cara lives in the DC metro area with their spouse and child.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m 44 years old. I’ve been writing stories since I was in preschool. My first stories were on tracing paper, bound with yarn. I drew pictures in crayon and narrated the text to my mom. I wish I still had those early stories. In high school, I really committed to writing, writing for my school newspaper and my small-town newspaper. More importantly, that was when I began to document my life. I wrote about life, passing back and forth notebooks with friends, as well as on my own, in my diary.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Everything is Fine, I’ll Just Work Harder: Confessions of a Former Badass, April 2025.

What number book is this for you?

This is my debut book!

Everything is Fine, I’ll Just Work Harder is a graphic memoir that tells the story of living with the aftermath of trauma until I couldn’t, when a trigger reawakened that traumatic experience and my coping strategies failed. The book interweaves research which reflects my nerdy love of research deep dives, the research that saved me and helped me to know myself in more informed ways. And it's a memoir about my journey through therapy to heal.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

My book is a technically a graphic memoir. But “graphic memoir” always feels a bit too fancy to me. I like to say I make comics. But they’re not “funny, haha” comics, they’re comics about vulnerable stuff that I hope people can relate to. My book is a unique graphic memoir. It’s a very personal story that is interwoven with strands of research, because I’m a big nerd, and research deep dives are what helped to save me.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Everything is Fine, I’ll Just Work Harder is a graphic memoir that tells the story of living with the aftermath of trauma until I couldn’t, when a trigger reawakened that traumatic experience and my coping strategies failed. The book interweaves research which reflects my nerdy love of research deep dives, the research that saved me and helped me to know myself in more informed ways. And it's a memoir about my journey through therapy to heal.

Everything is Fine, I’ll Just Work Harder is not just my story—it is the story of many people who’ve survived sexual assault. It is also the story of many queer people and the abandonment that they face from their families. Ultimately this is also the story of how another world is possible for us all.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

As a kid, I dreamed of writing a book. My grandmother always believed that I’d write a book one day. In high school, I wanted to become a journalist. I was on my school newspaper, editing the sports section, which makes me laugh now—no one else wanted that position, so editor friends pushed me to do it. I also interned at the local paper.

But I really began to become a writer of memoir when I was a teenager trying to figure out who I was. I kept a diary. That diary changed my life for better and worse in so many ways. I don’t want to say more as it’s part of my memoir—you’ll have to read it to find out why the diary was so important.

During my first year of college, I imagined that journalism would be my future. Instead, I became fascinated with science—beginning with neuroscience and neuropsychiatry, and then ecology. I went to grad school to study evolutionary biology. As a biology professor, I write a lot but in a very academic format. I found my way back to writing memoir through comics.

This book is a story—several stories, actually, that are deeply intertwined—that I felt compelled to tell. The overarching story is of how I went to therapy to heal from one trauma, a sexual assault. But often when you start to unpack one trauma, the rest comes tumbling out. For me, the rest included the deep trauma of familial homophobia, that shaped who I am. I had to get the story out of my body and onto paper.

Comics are my medium. Comics gave me the freedom to tell a story about trauma, using visual metaphors and pacing through panels in a way that shows how we feel and experience trauma responses in our bodies.

I began to make this book as a gift to myself. Besides therapy, it’s the hardest and best thing I’ve done for myself. Now, it doesn’t feel like just my story anymore. I hope it’s a useful gift for others to see a path forward—for us all to feel less alone as we do this work to come home to ourselves.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

For me, there were three hard aspects to writing this book: trusting the process of writing; the loneliness of writing a book; and the reliving of some of the trauma. Writing a book is an emotional process. It’s a rollercoaster, a feelings-wheel of all the feels. I tried to lean into trusting in the process, to normalize everything I experienced—resistance, impatience, frustration, joy, gratitude, being in the flow—it is all part of the writing process. And everything passes.

Being in this space, committed to birthing this project, I felt isolated. No one can write your book for you. While I was deeply compelled to tell this story, the process of telling it was long, winding, and at times lonely. I’m so grateful for Sequential Artists Workshop (SAW). Tom Hart, Beth Trembley, and Vanessa Davis created spaces for cartoonists working on graphic memoirs to show up to offer each other constructive feedback. That community sustained me through this process. Through SAW, I joined a critique group, and those three lovely humans continue to help me orient to my north star of my comic-making journey.

I found it hard to write this book at times. I’d spent so much time working through these traumas, and yet small shards remained. I offered myself lots of tenderness when I’d find these tiny shards. This book required me to nurture these old wounds in new ways. I learned to put aside the book when I needed to take care of myself. I learned to be with my grief in new ways, to trust that I could move through it as it flowed through me.

From this process, I learned that I now know in my body when my writing is ready to be shared. It took me numerous drafts and rounds of pitching to recognize that embodied gut sense.

Before I found a publisher for the book, an excerpt of the book was published as a comic in the Washington Post. This part of the book was hugely important to me to share with the world. The comic was about tonic immobility, a physiological state of being frozen during a trauma. This is an innate passive defense that is automatic, instinctual, and not a choice. Many people experience tonic immobility during sexual assault. Learning about this passive defense helped me release the blame I heaped on myself after sexual assault. I want others to find freedom from self-blame through the gift of this knowledge, so that we as a society can place responsibility for harm where it squarely belongs—on perpetrators.

And after publishing this comic, I didn’t expect anything else to come of my book project. But months after I’d pitched, as is sometimes the case in publishing world, a publisher reached out, interested to see the full manuscript. I reworked the whole book and pitched it again to several indie presses. And my book found a home at Street Noise Books. I can’t say enough great things about the Street Noise team and how much my book evolved through their thoughtful editing process. I’m so delighted with how it turned out.

This book is a story—several stories, actually, that are deeply intertwined—that I felt compelled to tell. The overarching story is of how I went to therapy to heal from one trauma, a sexual assault. But often when you start to unpack one trauma, the rest comes tumbling out. For me, the rest included the deep trauma of familial homophobia, that shaped who I am. I had to get the story out of my body and onto paper.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

Memoir is true and it is fictionalized because it’s storified. Some people in my life became characters in the book. But I used very few names in the story. For those people actively in my life, I offered them the opportunity to review the book and share their reflections about it. A few read it in full, and a few read sections.

This is my story. I did not share it with people whom I love but who are no longer present in my life. I wish them no harm through this story, but ultimately their reactions are their own.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

Four graphic memoirs were particularly inspiring to me. I deeply appreciated the intimate narration of Teresa Wong’s first book, Dear Scarlet. It’s such a powerful and deeply moving story in its vulnerability. Georgia Weber’s Dumb really showcased the power of images in comics. Erin Williams’ graphic memoir Commute is hella gutsy. Her interweaving of the mundane yet profound everyday experience of moving through the world as a survivor, what plays out in moment-to-moment interactions, inspired me to be brave. And as I was nearing the end of writing my book, Tessa Hulls’ book, Feeding Ghosts, came out. Tessa’s book blew my mind in its rich complexity of familial emotions and history.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Please give yourself so much kindness and tender care. Take breaks. Find your people to support you through the process. Your story is worth telling. There are so many stories the world needs to hear.

What do you love about writing?

Making comics is magic. I love that everyone has their own style. I love how my own style is continually evolving. I love the space comics offers me. I love the way stories can dance on the page.

What frustrates you about writing?

The continual letting go and trusting in the process—I’m not sure if that gets easier? At least it hasn’t quite yet for me.

What about writing surprises you?

How necessary it feels.

I found it hard to write this book at times. I’d spent so much time working through these traumas, and yet small shards remained. I offered myself lots of tenderness when I’d find these tiny shards. This book required me to nurture these old wounds in new ways. I learned to put aside the book when I needed to take care of myself. I learned to be with my grief in new ways, to trust that I could move through it as it flowed through me.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

Oof. To finish this book, I drew one page every morning and one page every evening until I was done. More generally, however, I don’t subscribe to a routine for writing and drawing. I do give myself unscripted drawing time simply for myself every day. It’s a deep pleasure that I savor.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I find research deep dives to be deeply creative. I love quenching my curiosity. I love the winding nature of a deep dive. It’s something I do both professionally as a professor and researcher and for fun.

I find walking often helps me to work out the next part of my writing.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I’m working on a series of braided comic essays. I’m compassionately curious about the emotional inheritance of parenting while estranged from my parents, and the freedom, grief, and growth inherent in that experience. I’m also deeply concerned about our larger inheritance of climate change. I’m excited to see this second book beginning to take shape.

I loved everything she said!

Love to see Cara in this space!