The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #3: Leslie Jamison

"I always conceived of this as a book about simultaneity—the way life is often pointed a few ways at once; in this case, toward love and toward grief."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

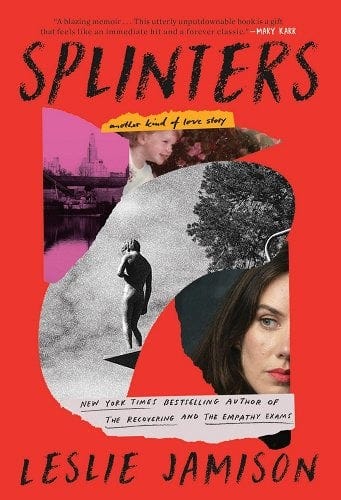

Here’s the third installment, featuring Leslie Jamison, bestselling author, most recently of the memoir, Splinters: Another kind of love story. -Sari Botton

Leslie Jamison is the New York Times bestselling author of The Empathy Exams; The Recovering: Intoxication and its Aftermath; Make it Scream, Make it Burn; and The Gin Closet, and—most recently—a memoir called Splinters: Another kind of love story. She writes frequently for various publications including The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The New York Review of Books, and The Virginia Quarterly Review. She directs the nonfiction writing program at Columbia University, and lives in Brooklyn with her family.

--

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

40.

I’ve been writing for 35 years; even before I could literally write, I was so eager to tell stories that I would force my older brothers to transcribe the fairy tales I’d invented. But I published my first book—a novel called The Gin Closet, a much darker kind of fairy tale—when I was 26 years old, so 14 years ago.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Splinters: Another kind of love story. Feb 20, 2024.

What number book is this for you?

My fifth book.

Splinters tells the story of the birth of my daughter and the end of my marriage, these simultaneous experiences twined like a double helix plotline through the book. It illuminates my consuming love for my daughter, and the rupture of my marriage falling apart, examining what it means for a woman to be many things at once: a mother, an artist, a teacher, a lover.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

Splinters is a memoir. Of all the books I’ve written, this is the first that I feel comfortable using that designation for—I’ve written a novel, two essay collections, and a book that I often call a critical memoir (The Recovering) that blends personal narrative, cultural history, literary criticism, and reportage. But it’s really a book-length essay.

With Splinters, I’m thrilled to have the chance to embrace the category of memoir. This book knew its shape and voice and structure early: it knew it wanted to be composed of these whittled, utterly distilled shards of experience; to stay close to my subjectivity and my sensory experience; and to drill as deep into consciousness as possible.

I think sometimes the word “memoir” can make people want to shy away—as if there’s some shame or compromised ambition in “just” telling a personal story, as if there’s a lack of ambition embedded in that just. But I believe so deeply that personal narrative can hold infinite richness.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Splinters tells the story of the birth of my daughter and the end of my marriage, these simultaneous experiences twined like a double helix plotline through the book. It illuminates my consuming love for my daughter, and the rupture of my marriage falling apart, examining what it means for a woman to be many things at once: a mother, an artist, a teacher, a lover. How do we move forward into joy when we are haunted by loss? How do we claim hope alongside the harm we’ve caused? I think of Splinters as a book that grieves the departure of one love even as it celebrates the arrival of another.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

In many ways, I feel like I spent fifteen years developing my voice and my craft so that I could tell, the best way I could, the hardest story I would ever tell: this period of pain and vulnerability, but to bring everything I could to that vulnerability as a craftswoman, as a writer of sentences and a sculptor of scenes. I always conceived of this as a book about simultaneity—the way life is often pointed a few ways at once; in this case, toward love and toward grief.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

The hardest part of writing this book was figuring out how (and how much) to tell the story of my marriage. I always conceived of this book as telling the story of the aftermath—what happened after my marriage fell apart, as my daughter and I were building a new life. But I knew I needed to tell some of the story of the marriage itself in order to grant that aftermath emotional resonance and impact. As my friend Mary (the great memoirist Mary Karr) put it: “You don’t write the heartbreak of divorce by writing the brutality of the divorce; you write the heartbreak of divorce by writing the love that came before.”

As I do with all my personal nonfiction, I shared the entire manuscript with everyone who appears in it, almost a year (or more) ahead of publication, and invited their thoughts and feedback, which I incorporated into my editing process. (Though I do not promise to change everything they want me to change, I do promise to take their feedback seriously, and I always make some changes based on what they say.)

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

I refer to most of the men in the book by nicknames or by initial. Not to be reductive or distancing, but to acknowledge that I am aware that I am essentially creating them as characters—not by fabricating anything (everything is true) but by virtue of being the one constructing and curating the story. Every time we tell a story about other people we are constructing them as characters, as ourselves as well.

I call my ex-husband “C,” not because I’m naïve and think people don’t know how to do a google search, but for this reason—as an acknowledgment of the fact that who he is in the pages of my book is a character; distinct from him in real life, even if everything in these pages actually happened.

As I do with all my personal nonfiction, I shared the entire manuscript with everyone who appears in it, almost a year (or more) ahead of publication, and invited their thoughts and feedback, which I incorporated into my editing process. (Though I do not promise to change everything they want me to change, I do promise to take their feedback seriously, and I always make some changes based on what they say.)

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work?

Splinters has a flock of what I call “godmother texts,” existing texts by other female writers that have explored (often obliquely) the work and beauty of building another kind of life in the aftermath of a ruptured marriage: Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights, Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living, and Susan Taubes’ Divorcing. I like the phrase “godmother texts” because it suggests inspiration, permission, and alternate forms of nurturing and motherhood.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

I’ll pass along two pieces of advice that changed the way I live and the way I write, both from my teacher and mentor Charlie D’Ambrosio. In workshop, he told us, abandon your citizen self. And to me that means that I can’t write to please other people; and I can’t write the sugar-coated version of the story. I need to write into the hard parts, the shameful parts, the difficult parts that won’t please anyone. He also told me once, after reading an early draft of the essay that became “The Empathy Exams,” that “sometimes the problem with an essay can become its subject.” Meaning (among other things) that sometimes the things that seem most difficult about a given project are also the reason it's meaningful at all—which is a way of saying, perhaps the aspects of the project that scare you the most are also the very things that make it worth writing. Sometimes that can be a solace.

What do you love about writing?

I love arriving at a detail, sentence, or moment that feels just right on the fourth or fifth draft, after many hard revisions—feeling that all that hard work was necessary to get to this effortless, perfect brushstroke. It pushes back against the idea that the prose that feels effortless actually was effortless—and that’s liberating.

What frustrates you about writing?

Part of my drafting process involves substantial amounts of repetition—saying the same idea ten times, in order to get to the one iteration or articulation I actually need—and there’s something deeply embarrassing about being so repetitive. But I also believe that a little bit of embarrassment can be a useful guide in the writing process.

Splinters has a flock of what I call “godmother texts,” existing texts by other female writers that have explored (often obliquely) the work and beauty of building another kind of life in the aftermath of a ruptured marriage: Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights, Deborah Levy’s Cost of Living, and Susan Taubes’ Divorcing.

What about writing surprises you?

Where a draft takes me. What ends up being part of the story. In Splinters, for example, I didn’t know that my parents’ marriage would become such an important thread in the book—but I believe in that thread, because it ambushed me; its presence feels organic rather than forced.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

My conversations with friends. Long letters. Long walks.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I am working on two more books: a book about daydreaming that brings together personal narrative, cultural history, and reportage; and a novel that begins with the story of the minotaur’s mother and moves through time to tell the story of a cult of twenty-first century women who worship her. It’s a novel about monstrosity, maternity, and community.

SPLINTERS sounds like the love-and-loss story so many of us would write if we could. Also, I love the idea of godmother texts.

I'm so excited that Leslie Jamison is going to write a novel about the Minotaur's mother. In the novel Circe, Madeleine Miller writes about Pasiphae giving birth to the Minotaur and it's so painful and literal, but also funny--I've been thinking about it for years. I have so many other things I should be doing this morning, but after reading this interview I can tell I'm just going to have to sit here rereading that scene. Thanks, Sari!