The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #87: Diane Mehta

"Be yourself in prose, allow ideas to emerge, and go on riffs—into brambly, wild places. I don’t mean let just anything happen, but follow your mind."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

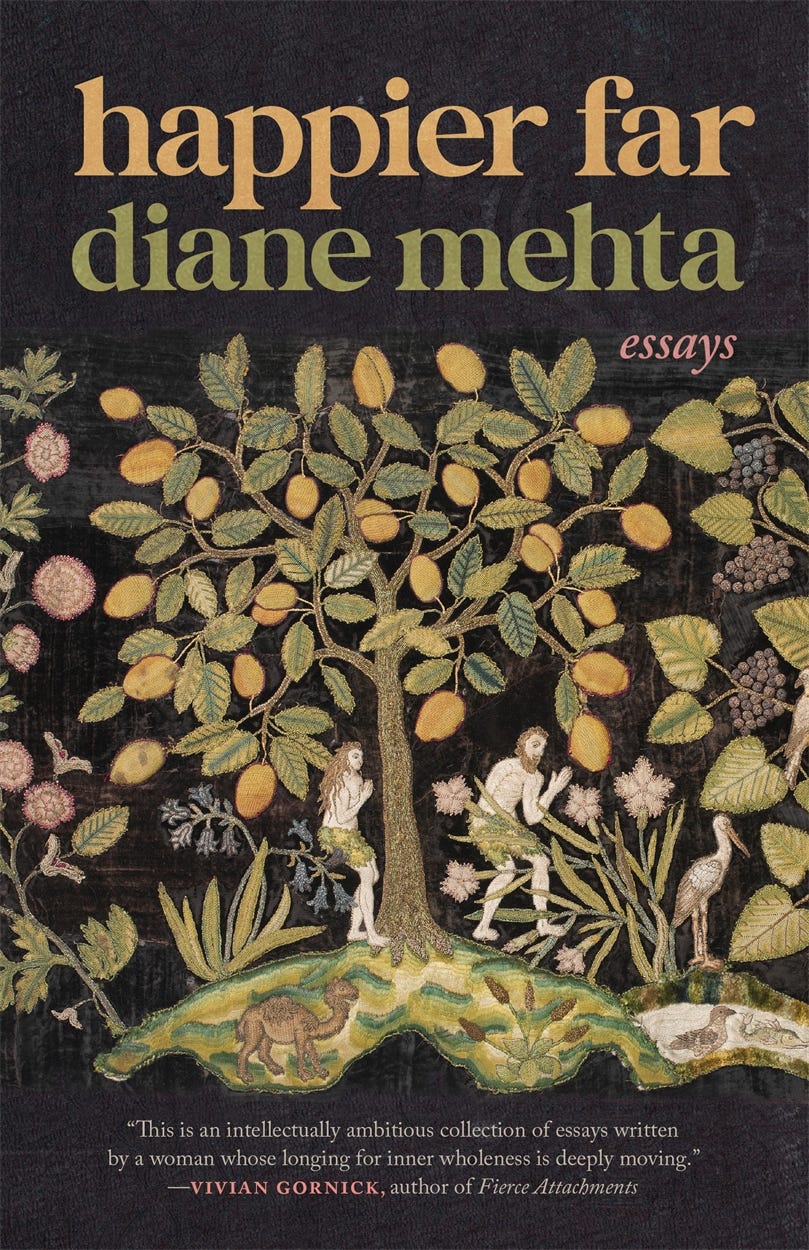

Here’s the 87th installment, featuring , author most recently of Happier Far: Essays. -Sari Botton

P.S. Check out all the interviews in The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire series.

Diane Mehta is the author of the essay collection Happier Far, out in March 2025. She also has two poetry books: Tiny Extravaganzas (2023) and Forest with Castanets (2019), and her writing has been recognized by the Café Royal Cultural Foundation and fellowships at Civitella Ranieri and Yaddo. Her work is in The New Yorker, VQR, and Kenyon Review. She is poet in residence with the New Chamber Ballet in New York City, and her first poem about a dancer was in the New Yorker. Her poem Plum Cake is in the 2025 New Yorker anthology A Century of Poetry in The New Yorker: 1925-2025. This year, she was a judge for the Arrowsmith-Derek Walcott poetry prize and the 2025 Silvers-Dudley journalism prizes.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m 58 and I’ve been writing for nearly 50 years.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Happier Far: Essays, published March 15, 2025.

What number book is this for you?

Four.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

It’s a memoir in essays because the link is a chronological story of “becoming”—from (literally) birth and a childhood in India and New Jersey to the life experiences we all enter and exit, from marriage and a kid to divorce and single parenting, and from trying to make sense of it all to figuring out that making sense is really more of an interrogation of memory while working on the next thing and the next.

Happier Far is a memoir in essays because the link is a chronological story of “becoming”—from (literally) birth and a childhood in India and New Jersey to the life experiences we all enter and exit, from marriage and a kid to divorce and single parenting, and from trying to make sense of it all to figuring out that making sense is really more of an interrogation of memory while working on the next thing and the next.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I came to America when I was seven years old. New Jersey was an unwelcoming place for Asians in the seventies, and my mixed-race Jain-Jewish parents weren’t a fit for the suburbs or for one another. I was often alone, scribbling away in a wild frenzy, and producing what I think of now as fragments of Revelations-style poems. By high school, I had figured out that something creative was happening, and that these were disorganized poems—so I started paying attention to what I was putting on the page and how to do a better job. I also longed to be a singer or a dancer, and what I realize now is that like literature, song and dance work with timing, duration, and training, so it adds up: sentence, gesture, rhythm, pattern.

Writing essays didn’t seem like a natural fit for at least half of my writing career—especially after reading Ralph Waldo Emerson when young and feeling awfully confused about circles. One day, in the heat of frustration, I wrote about a reading slump I’d fallen into, and produced a reflection on not reading. The Paris Review Daily took it immediately, and so I was chuffed, and ready to grapple with what an essay can do. It took nearly a decade to work out a style that was rhythmic and tender, and years more to become efficient and calculated about what I wanted to discover and achieve while writing the essay.

This book came together by paying close attention to the flow and allowing a certain rhythm to emerge. I was relentless about not putting in as much as I had originally planned, in order to keep it focused. I added motifs (five minutes) and funny moments, and let myself rant and associate in ways that my mind is good at; this, it turned out, was also good for my essays. I tied sentences beat by beat together, as a poet, and started seeing connections between essays. Many grueling drafts later, aided by an enormous about of research (especially the essays on India and Brooklyn), I settled on an approach. The research and history was a thrill, and way to connect the essays while panning out and trying to see the world around me more clearly.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

Relentless editing and rewriting from scratch over and over, and over many years. There’s no end to editing. As Rudolf Nureyev said, of his dancing, “How much you need to use scissors.”

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

My mother is dead so I live out our relationship on the page. My father is 92 and I’ve written what I’ve wanted to, about him and my mother, as well as my personal life, and he has responded with enthusiasm, though while reading the final proof, he kept his opinion of what I observed about him and my parents’ marriage to himself, and, in character, simply said: “I’m only going to make comments on facts.” He found a few mistakes, and so I changed those. One person I wrote about freely, and only told her a few months ago. I think she’ll love it because it’s kind of an idyll with and for her, and in the story I tell about discovering her, during my time with her, I make it clear how much she means to me, and I honor her remarkable career in Indian and Jain art.

This book really came together by allowing a certain rhythm to emerge and by being relentless about not putting in as much as I intended, to keep it focused. I added motifs (five minutes) and funny moments, and let myself rant and associate in ways that my mind is good at; this, it turned out, was also good for my essays. Then I’d tie things beat by beat together, as a poet, and started seeing connections between essays.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

Charles D’Ambrosio’s Loitering: New & Collected Essays and James Baldwin’s Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region of My Mind" in his book Fire Next Time changed the way I thought essays could evolve and move. They both tell slow, idiomatic stories about delicate subjects, and are meticulous on the line while stepping back and suddenly opening up or finding a revelatory moment in a poignant scene or memory—all while twirling into the spirit of the telling, perhaps going a little mad, but the writing holds them up and so they take the writing on a ride, looking around and pointing the finger as they go.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Be yourself in prose, allow ideas to emerge, and go on riffs—into brambly, wild places. I don’t mean let just anything happen, but follow your mind. Writing is like a Venn Diagram, with overlaps or connections. I vote for letting everything tumbleweed together over multiple drafts and editing on the printed page (edit, print, edit, print) and recording out loud to see if it’s working. Every wrong moment leaps out when recording—the tongue gets knotted and words jam together or lose interest in themselves pretty quickly. I record everything, and it helps.

What do you love about writing?

Slipping into it and losing myself, and then editing, shaving, polishing, and getting the main idea pinned down, finally, after the see-saw of confidence and gloom.

What frustrates you about writing?

Two things: My own drafts and how long they take. And the vacuum in my head when I finish something and feel like I’ll never start again.

What about writing surprises you?

There’s always an again.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

I write from the moment I get up, over breakfast, until noon every day, even on vacation, and I make no exceptions, ever.

My mother is dead so I live out our relationship on the page. My father is 92 and I’ve written what I’ve wanted to, about him and my mother, as well as my personal life, and he has responded with enthusiasm, though while reading the final proof, he kept his opinion of what I observed about him and my parents’ marriage to himself, and, in character, simply said: “I’m only going to make comments on facts.” He found a few mistakes, and so I changed those.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I’m immersed in multiple collaborations. Working with other artists buoys and structures my own, and the commitment to collaborating over years rather than weeks or months not only influences the depth of collaboration and what emerges, but time together becomes the collaboration. I’m fifteen months into a collaboration with the New Chamber Ballet in New York City. I’ve been writing poems about the dancers, and now am poet in residence. Something shifted as we made a commitment to the process, and over time to creating a collaborative ballet (June 2025).

I also love swimming, which has a rhythm. It frees my mind utterly, and my body measures the water the way we all measure movement in writing and in life. Everything is blue. Walking also feeds my thinking and I concentrate better while moving.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I have a novel set in 1946 India that my agent will shop later this year or next. Two nonfiction books are emerging slowly: about working with a ballet for several years and about how reading Dante changed my entire oeuvre, or rule of being, way of being, and gave me two remarkable friends. I’m toying with a third novella about a group of young women at a boarding school who don’t follow any rules and neither does the school. And I’m working on a poetry manuscript about the ballet.

So many wonderful tidbits of inspiration in this interview. Thank you so much! 🩷

“the see-saw of confidence and gloom.” That’s it! What a glorious way to put it. Thank you, Sari and Diane, for this beautiful interview.