The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #97: Matthew Specktor

"The book does render my experience, and faithfully, but it’s really about other stuff...this is actually a book about power."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

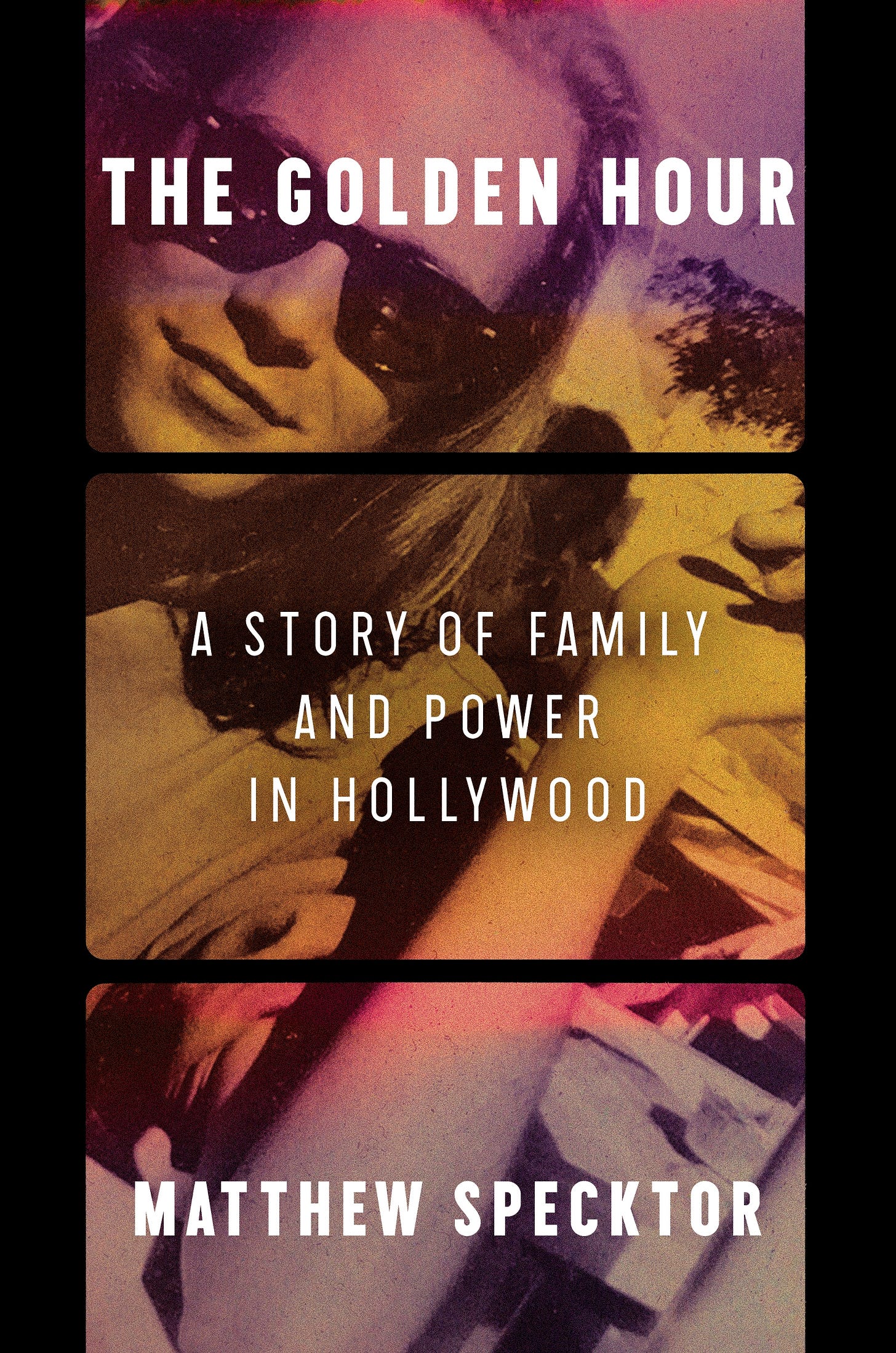

Here’s the 97th installment, featuring Matthew Specktor, author most recently of The Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood. -Sari Botton

P.S. Check out all the interviews in The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire series.

Matthew Specktor’s books include the memoirs The Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood and Always Crashing in The Same Car, and the novels American Dream Machine and That Summertime Sound. He is a founding editor of The Los Angeles Review of Books.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m (good grief!) 58, which means I started writing seriously forty years ago. I took a class with James Baldwin—he was my undergraduate writing professor—and that was pretty much it, though I’d had some designs on doing it even in high school. It wasn’t until my mid-20s that I was able to really stand anything I’d written, though. Until then I wrote things, crumpled them up and threw them away (or . . . dragged them into the trash bin on a chunky, primitive laptop. I’m old enough to have started on an IBM Selectric II, though).

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

The Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood, published in April 2025.

What number book is this for you?

Five. Although, if you count the ones I’ve completed and abandoned—which I’d like to: there were two before I published my first, and another between books three and four—it’s technically number eight.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

It’s a memoir, but it must be said that I’m a novelist, and this book avails itself frequently of a novelist’s prerogatives: much of it is written from the perspectives of people who aren’t me, many scenes are rendered (in the book’s first half especially) in which I am not even present, etc. So it’s both a memoir and a . . . nonfiction novel, I suppose, even though I find that term a little suspect. But, and this really is the novelist in me speaking, I was never particularly interested in a straightforward rendering my own experience.

The book does render my experience, and faithfully, but it’s really about other stuff. While I was writing it I described it to people, slightly but not entirely facetiously, as a “systems memoir,” which—like the so-called “systems novel”—is more about the cultural and economic systems that surround the individual (me) than it is about myself. Which is to say, power: this is actually a book about power.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

It’s the story of how the traditional motion picture industry died, and of how this peculiar thing—“The Movies,” which were both America’s greatest cultural contribution throughout the 20th Century and its strongest export—reflected and shaped the peak of American empire. It’s that, told through an acutely personal narrative: my father was (and still is, into his 90s) a fantastically successful talent agent; my mother was a somewhat less successful screenwriter and would-be novelist, a gifted person with some fairly severe emotional, substance-related, difficulties; I was, briefly, a tremendously ambivalent studio executive and then a working screenwriter myself. The tension between these things—between art, creative labor, and capitalism; between American self-image and American reality—seemed worth exploring, and are really what the book is about.

The Golden Hour is a memoir, but it must be said that I’m a novelist, and this book avails itself frequently of a novelist’s prerogatives: much of it is written from the perspectives of people who aren’t me, many scenes are rendered (in the book’s first half especially) in which I am not even present, etc. So it’s both a memoir and a . . . nonfiction novel, I suppose, even though I find that term a little suspect.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

Well, the example was there early on. My father got up in the morning, put on a suit, and hurried off to the office. My mother got up, put on her sweats, poured a cup of coffee, poured a second cup, smoked a cigarette, and wandered off to the little shed behind our house where she spent her time . . . daydreaming, and sometimes typing. When she felt like it, she took a nap or went to the movies in the middle of the day or sat around reading. My father’s suits were fantastic (they got nicer as time went on and he became more successful, though this didn’t happen until I was out of the house), but you can guess which one of these paths appealed to me—a Gen X teenager with an anti-authoritarian streak—more.

Over the years, as my own experience accumulated, both personal (marriage, divorce, becoming a parent, losing a parent) and professional (going to work for a talent agency at 14 years old, working for Robert De Niro in my 20s, becoming a senior executive at a studio, writing screenplays and seeing how films do and do not get made) I became aware a memoir might be in the cards. But again—I’m a novelist! That’s the tradition I work out of, and my fiction is usually personally sourced (but not quite as “autobiographical” as it may present) while my memoirs (I guess now that there are two I can use the plural) always seem to need to create space for imagined or invented material.

This book in particular grew out of a specific moment I witnessed in 1998, wherein Rupert Murdoch and others were in a room (I was there) and one of Murdoch’s henchmen made a remark that I knew betokened the end of an American creative middle-class. I wanted to write about that, specifically. About what killed the middle class in America.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

I was lucky enough to sell this book on proposal, so the path to publication was pretty smooth: I wrote an email to my agent, we teased that out into a proposal (of which there were multiple drafts, over a few months), and it sold quickly. Writing it, of course, was a different story. I must have written the first 50 pages (first 100 . . . once I think I got about a 175 in) at least a dozen times before I really gained traction?

The hardest part was squaring the balance of personal narrative with the wider historical story being told, finding a way to move comfortably between those two poles. I wanted the book to be both intimate and grand, and finding a way to do that in a way that, also, felt natural, was a challenge to say the least. Finding that balance, too, between memoir and invention, clear lanes through territory that in a few places had already been mythologized to death elsewhere. That was a real nightmare for a while.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

Weirdly—for the first time in my writing life—I used real names for everybody, both for family members, friends, ex-partners, and for the historical figures in the book. It wouldn’t have worked any other way. I suppose, since I’m a very private writer—I try not to show things I’m writing to anyone until the last possible moment—I managed to convince myself while I was working that nobody was ever going to read it. Or (this is probably more accurate, since of course I knew people would read it, having sold it before I started writing it) managed to sort of . . . forestall those concerns until I finished.

No changes were requested by those people when they read it, beyond a couple of corrections that grew from lapses in my own memory, and for the most part (I stress that, as I type this, many people who are depicted in the book have yet to read it) their responses to the book have been immensely positive. That won’t be true for everyone (I’ve lost a friend or two over the years to things I’ve written), but I don’t know.

I don’t write to settle scores. I don’t think I’ve ever written anything—I’ve certainly never published anything—in which I’m harder on anyone else than I am on myself, and that applies especially to people with whom my relationships have been fractious or complicated. I’m not interested in that. But at the same time, “memoir,” “fiction” . . . I think of these things both as products of the imagination. They’re not meant to be definitive.

It’s always possible that someone’s going to feel hurt or insulted by something one has written (and it’s been my experience that those people who do feel this are almost never the ones you suspect could feel that way), but this possibility, at least, is unavoidable. It’s the price of the ticket, really.

My father was (and still is, into his 90s) a fantastically successful talent agent; my mother was a somewhat less successful screenwriter and would-be novelist, a gifted person with some fairly severe emotional, substance-related, difficulties; I was, briefly, a tremendously ambivalent studio executive and then a working screenwriter myself. The tension between these things—between art, creative labor, and capitalism; between American self-image and American reality—seemed worth exploring, and are really what the book is about.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

Well, of course there are too many to mention—writing really does grow from one’s reading—but in this case there were a few who loomed particularly large. Don DeLillo, whose novels I reread in order while writing, both because he factors into the book in few places (albeit peripherally) and because I think he defined certain aspects of the late 20th Century, the cinematic century, better than anyone. James Joyce, because he was my mother’s favorite writer, and her story—specifically, her story as an artist—is central to the book. I reread Ulysses, and portions of Finnegans Wake, while I was writing also. And James Baldwin, because he's depicted in the book and was my first, most influential teacher. A thoroughly daunting trinity, obviously, but those are the ones who presented themselves in this case. Obviously, there are others—shoutout to all the writers both living and dead who presented themselves to my attention while I was writing (Charles Portis! Garielle Lutz! My friend Emily Segal, and her wonderful novel-in-progress!)—but those three were central to this project.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Look, writing is, in the truest sense, a small-d democratic process. Every writer is afraid (if they’re not, they should be), every writer is intimidated by the ungodly complications of trying to render experience in words. It’s true that once you’ve done it long enough you learn that your feeling of being completely helpless in the face of what you’re trying to say is transitory—that it is, in fact, a necessary precondition of being able to say it at all—but it’s the same every time. Which is really to say: you CAN do it. Seriously. If you have a high enough tolerance for failure (meaning, if you’re willing to throw out what you’ve written and start over a few times—or maybe more than a few), if you’re willing to be honest with yourself and exacting (which, once you get past the feeling of discouragement, is always about renewing one’s excitement about the material and making the book better) you absolutely can write the book you’re trying to.

Maybe that sounds less “encouraging” than it’s supposed to, but I mean it in the most concrete and forthright sense. When I was writing my first book, many years ago, I wondered if I’d ever finish it. It seemed like a mystic process of some sort. It wasn’t. It isn’t. It’s like cooking. You probably have to scorch a few pancakes unless you’re very lucky, but you have the ingredients and you have the stove and if you find yourself confronted, the first few times, with inedible results, well, like I said, that happens to everybody. (It’s cooking . . . but where the ingredients are private and you don’t really know how to combine them and there’s no written recipe. You have to do it on the fly, and by looking over your neighbor’s shoulder.)

The only other piece of advice I’d offer is something Salman Rushdie said in an essay he wrote about The Tin Drum in Granta, sometime in the mid-80s. “Go for broke. Always try and do too much. Dispense with safety nets.” Max it out. You’re going to fail anyway—“fail” in the sense that no book is ever going to be as absolute as you want it to be, not fail in the worldly sense of publication—so aim for the stars. Your stars, which are nobody else’s. Which is precisely why everybody else, perhaps, needs to see them.

What do you love about writing?

Everything, but above all else the sense of absorption. Of being present and attentive, away from the distracting pull of the internet and everything else. The deep, deep concentration.

What frustrates you about writing?

The understanding that it happens in its own time. One feels, often, one is “supposed to be working” or that one is frittering—I feel that way, at least—but for the writing that’s most personal, and most valuable? That tends to happen on its own clock. Even with deadline-driven writing, I find myself thinking “Well, I should be able to knock this out,” and then finding I can’t. I’ve never in my life missed a deadline, but there’s always a period of inactivity where I’m marshalling my thoughts, not quite ready to set pen to paper. That frustrates the hell out of me.

What about writing surprises you?

The way it tends to happen behind my back, as it were. I’ll be struggling with a problem—or simply to start something—and no matter how energetically I throw myself at it, the door won’t open. Then—it does. The fact that it tends to work out its problems unconsciously, and that solutions often arrive fully formed (albeit always after periods of flailing and frustration). This never fails to astound.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

Usually, yes. There are times where the writing has to get done no matter where I am, so I’ve done it on planes, trains, in airports, on friends’ couches and so on, at any time of day, but usually I try to get to it first thing, before anything else has asserted itself to me as something that needs doing instead. I wake up, drink my coffee, and try to hop to before anything else suggests itself as more important (which, of course, sometimes it does and it is!) But I do my writing as early as I can, and then tend to the rest of my life after that, which I’m lucky to be able to do, usually, as a freelancer. When I’m in a project, I write every day, six days a week. When I’m not . . . all this goes out the window, and I get very, very cranky after a while. But, of course, those periods of not writing are important. The cisterns need to fill.

This book in particular grew out of a specific moment I witnessed in 1998, wherein Rupert Murdoch and others were in a room (I was there) and one of Murdoch’s henchmen made a remark that I knew betokened the end of an American creative middle-class. I wanted to write about that, specifically. About what killed the middle class in America.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

Like everybody in Los Angeles, hiking, long walks, gym-going, and pilates are part of my life. (I wish I’d known earlier how essential regular and sustained physical activity is to just about every aspect of life, but especially to creative life.) I’m a music nerd, a cinema nerd, and a baseball nerd, although my wonky writer’s back means I’m no longer much of a player. I cook, although hardly professionally. I’m a parent and a spouse. I’m a dog-owner, which is, uh, also something of an occupation in my particular case. (Do you like smart dogs? Get a miniature schnauzer! Do you like dogs who do not require much attention, with quiet dispositions? Get . . . something else.) I think of all of these things as creative pursuits—art tends to flourish when you’re giving it both conscious effort and unconscious attention, the attention it can only receive when you’re directing your conscious attention elsewhere. No doubt there are other artistic mediums I’d like to take up—play guitar! Learn photography!—but, man, I’m busy enough as it stands.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

Yes, a novel. It’s just starting to crystalize in mind, so I won’t—really, can’t—say much about it, but it has nothing to do with the motion picture industry, or with my family. I’m excited!

Thank you. It’s refreshing to think about my own memoir as an act of imagination —a fiction tethered to facts. That’s what made the writing of it joyful instead of painful.

Love the part where he says writing happens “behind my back” and problems get worked out unconsciously and solutions sometimes arrive fully formed.