The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #69: Sherrie Flick

"The memoir arose organically from an exploration of place. Me trying to figure out the why of where I came from, the why of how I could not seem to 'see' my homeland, even as I lived in it."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

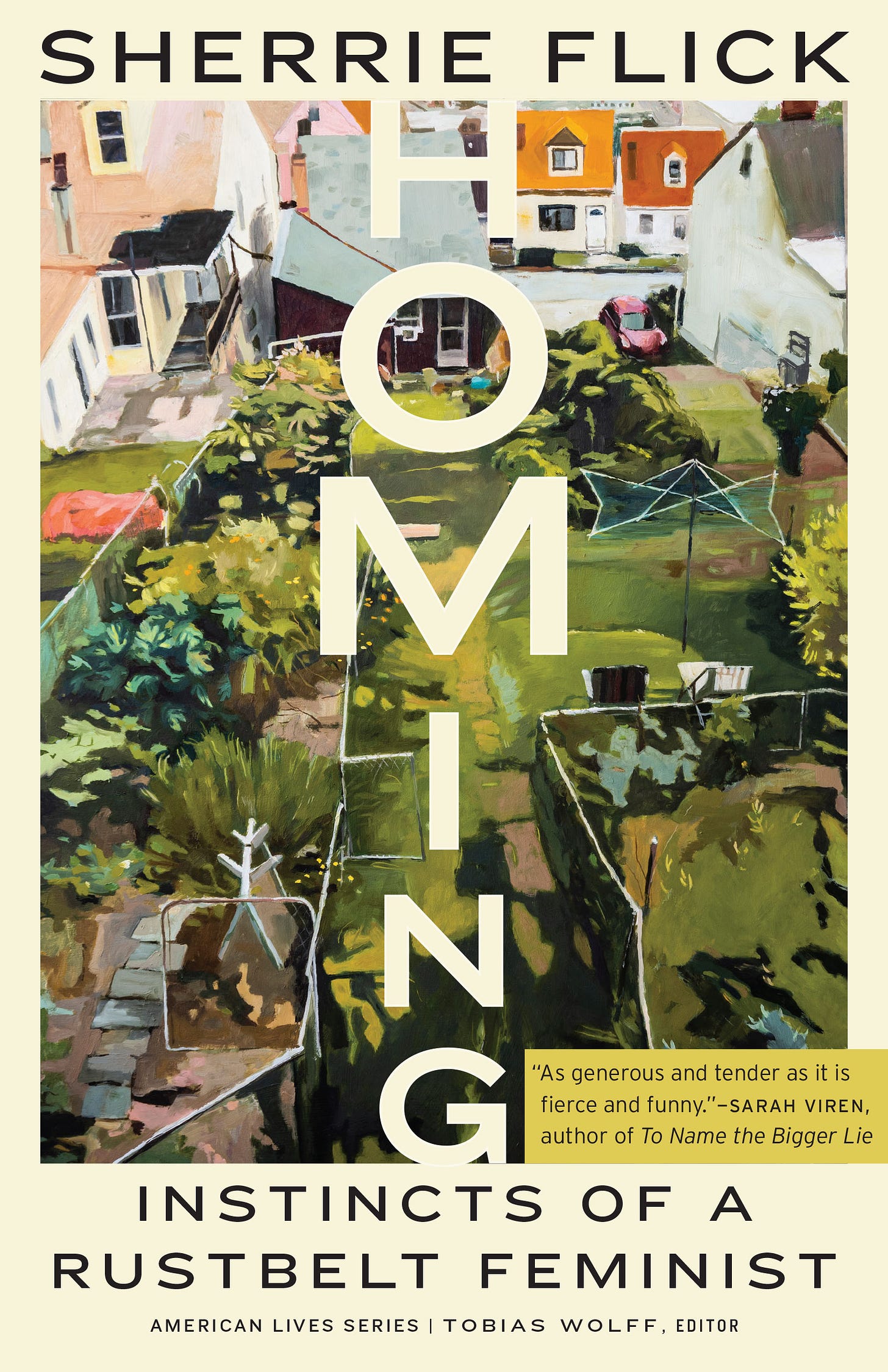

Here’s the 69th installment, featuring , author most recently of Homing: Instincts of a Rust Belt Feminist. -Sari Botton

Sherrie Flick is the 2025 McGee Distinguished Professor in Creative Writing at Davidson College. She received a 2023 Creative Development Grant from the Heinz Endowments and a Writing Pittsburgh fellowship from the Creative Nonfiction Foundation. She served as co-editor for the Norton anthology Flash Fiction America and series editor for The Best Small Fictions 2018. Her debut essay collection, Homing: Instincts of a Rustbelt Feminist, was published by University of Nebraska Press in September 2024 as part of their American Lives series. Her third story collection, I Have Not Considered Consequences, will release in April 2025 with Autumn House Press. Her other works include, Thank Your Lucky Stars: Short Stories, Whiskey, Etc.: Short (Short) Stories, and Reconsidering Happiness: A Novel.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m 57 and I started publishing short stories in my early 20s.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Homing: Instincts of a Rustbelt Feminist, September 2024, University of Nebraska Press.

What number book is this for you?

If I count my chapbook, five. I’ve also edited/co-edited two anthologies.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

I actually categorized my book as an essay collection and then my press noted, once we had reorganized the order of the essays, that it was actually a memoir-in-essays, which was/is a tiny bit stunning to me because I did not set out to write a memoir. Through a series of unlikely mishaps (one book being killed by the pandemic, me working to resurrect said book into an essay collection against all odds) the book came to explore my life, my coming of age as a creative person and feminist—rising out of a dead steel town, a town that gave its last gasp my senior year of high school.

The historic context of my life—having lived through the rise and fall of steel, having lived on the east and west coast plus the Great Plains, and then landing back in Western Pennsylvania again (Pittsburgh this time) to see the city try to and succeed at becoming a hipster destination—it ultimately all came together in the book not because of the places but because of me. The memoir arose organically from an exploration of place. Me trying to figure out the why of where I came from, the why of how I could not seem to “see” my homeland, even as I lived in it. It was a wild, winding path to a memoir-in-essays.

I actually categorized my book as an essay collection and then my press noted, once we had reorganized the order of the essays, that it was actually a memoir-in-essays, which was/is a tiny bit stunning to me because I did not set out to write a memoir. Through a series of unlikely mishaps the book came to explore my life, my coming of age as a creative person and feminist—rising out of a dead steel town, a town that gave its last gasp my senior year of high school.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

The essays trace the creative coming of age of a mill-town feminist—me. My childhood spanned the 1970s rise and 1980s collapse of the steel industry. I returned to Pittsburgh in the late 1990s, witnessing the region’s before and its after. With essays braiding, unbraiding, and then tangling the story of my father with Andy Warhol, faith, dialect, labor, whiskey, Pittsburgh’s South Side Slopes neighborhood, grief, gardening, my compulsion to travel, and my reluctance to return home, I examine how place shaped my experiences of sexism and feminism. I also look at the changing food and art cultures and the unique geography that has historically kept this weird hilly place isolated from trendy change. Homing is an explicitly feminist, Gen-X, anti-nostalgic intervention in writing about the Rustbelt.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I’m a fiction writer who had no intention of writing nonfiction, except to pay some bills via freelance work. My main focus for the bulk of my career has been writing flash fiction—stories under 1,000 words. I was religiously dedicated to this form for the first decade of my career. These stories make up the bulk of my two short story collections. I eventually wrote and published a novel and ventured into longer short stories.

I also worked as a professional baker for many years and with this experience and my interest in foodways and food culture I was tapped in 2010 to create and teach a Writing About Food class for the new Food Studies graduate degree at my university. The class is a hybrid literature/writing class and through teaching it for the past 14 years I’ve come to think about nonfiction and creative nonfiction writing in a complex way. I’d written garden columns (also a huge gardener!) and freelanced writing profiles for branding firms and nonprofits, but I’d never committed to writing longform creative nonfiction until my friend Hattie Fletcher encouraged me to apply for a Writing Pittsburgh fellowship from the Creative Nonfiction Foundation. I proposed a project on the city steps in my neighborhood, the South Side Slopes. (There are 69 sets! Where I live it’s ridiculously steep and hilly.)

Through the workshops the fellowship offered and the encouragement of the people at Creative Nonfiction, I accidentally started writing a book. The book was going to explore old and new Pittsburgh—the decades I’d lived through—using research and interviews. The Foundation put the book under contract and when the pandemic hit I had 90,000 words written. And then, well, “old” and “new” became weird words since a global pandemic was at hand and funding became an issue and we all agreed (pretty quickly) to kill the project (and the book series).

It was surreal and devastating and I let that pile of Word.doc rubble just sit there for a while. The Foundation had wanted me to write a full book, not essays, and I’d always wanted the book to be essays, and so one day I realized I was, again, the boss of me, and I set out to pull what I liked from the giant heap of words. The chapters and excerpts and single paragraphs I yanked out started to tell a different story, which was a story about feminism and labor and grit and how memory works and the unlikely fact that I became a creative writer at all, considering the very uncultural (post)industrial world I grew up in.

I had a ton of research at hand from the old book. A ton of interviews that I could now reconsider in this new light. What resulted was a lean, mean manuscript of 41k words. I started sending out essays for publication and had some nice success with Ploughshares and New England Review and although the collection seemed short to me, on the advice of another friend who isn’t my agent but who is an agent, I sent it out to a few university presses I loved. I noted that I thought the book was short but that maybe we could work together to complete it with another essay or two.

That’s how my book was born. Courtney Ochsner at University of Nebraska Press was interested for their American Lives series and sent it out for peer review. Through some great peer review insight and commentary I came to write the final, very long essay in the collection, “Instincts.” I added a couple other essays that I pulled and revised from the old manuscript and it all clicked together to become Homing: Instincts of a Rustbelt Feminist.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

The whole concept behind the book was me trying to “see” a place that I theoretically knew well but had ignored for forever. I had to teach myself to observe a region that hadn’t previously interested me. I had to get into another place in my head, one that helped me reconceive my own life, put it into a historic context, think it through, and make connections across time. It was hard but ultimately completely challenging and engaging work.

As everyone likes to note: essay collections don’t sell, which is something that baffles me because I love essays. So I had to fight against the preconceived notion that the collection I was putting together would never see the light of day.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

For the most part I used real, full names in the book. There is a boyfriend or two that I just name “boyfriend” because we aren’t in contact anymore. I conducted a lot of interviews so most people I wrote about knew the book was coming and had a sense of the subject matter.

My goal was to be honest and to (as Chekhov advises) state the problem correctly. My job was not (as Chekhov advises) to solve the problem. In this way I tried very hard to write as honestly as I could in scene, without judgment. I wanted to be fair to the scene and to the people. That was the goal.

I didn’t run passages by anyone except a few sections I wanted some high school friends to verify, to make sure my memory was close to correct. I made some changes that they suggested.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

I’m a big fan of two Sarahs. Sarah Viren and Sarah Polley—their examination of truth and memory are really important to me. The fluidity of it all—emotional truth vs observed truth, how to merge them on the page. Sarah Viren’s two books: Mine and To Name the Bigger Lie and Sarah Polley’s Run Towards the Danger and her documentary Stories We Tell. Wow, all so important to me and what I tried to get onto the page.

On a longer arc I’ve always loved JoAnn Beard’s work. The Boys of My Youth and Festival Days in particular. She messes with the line between fiction and nonfiction in a way I love.

I also love James Baldwin’s essays for their exploration of large concepts and ideas.

Charles Simic was the first person who made me understand that writing about food was an important and worthwhile endeavor. I love his early essays.

The essays trace the creative coming of age of a mill-town feminist—me. My childhood spanned the 1970s rise and 1980s collapse of the steel industry. I returned to Pittsburgh in the late 1990s, witnessing the region’s before and its after. With essays braiding, unbraiding, and then tangling the story of my father with Andy Warhol, faith, dialect, labor, whiskey, Pittsburgh’s South Side Slopes neighborhood, grief, gardening, my compulsion to travel, and my reluctance to return home, I examine how place shaped my experiences of sexism and feminism.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

I think writing scenes from memory as a first step in the process is less intimidating than starting with research or interviews. After writing a detailed scene, ask yourself questions about it—those questions often lead to the research you need to do, the interviews you need to conduct. It’s a way to avoid over researching, I think. Stay bound to your scene writing. Really work on getting setting right and complex and layered. Write scenes that you own, that you know well, that haunt you. You are your own resource and expert in this way.

What do you love about writing?

There’s a lot to love. The process of thinking through the ideas and the drafting before it gets hard is something I love. My main love, though, is revision. I love having something to work with, to mold and refine. I am particularly in love with revising on the sentence level, trying to tighten my sentences to have the greatest meaning, trying to replicate the way we remember with structure and paragraphing. All of that laborious attention to detail is when I’m stuck to my seat unmoving for hours, deep into it. There isn’t anything better.

What frustrates you about writing?

The industry more than anything. There’s a lot of invisible labor even after a book is accepted that no one talks about. The exhaustion that sets in after you’ve gone to bat for yourself for months.

What about writing surprises you?

In writing this collection so many surprises came to me through the writing process itself. The connection between labor and creativity, for instance. I made that connection through the writing—I hadn’t thought about how the labor-centered steel industry, the heart of my hometown, influenced how I see work. How it pushed me to become a baker and how doing things with my hands helped me make sense of the world for a time. That kind of writing always surprises me. How I help myself understand myself and the world just by trying to tell a story, usually about something else entirely.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

I cycle through routines, sometimes writing every day for a whole semester from 7am-7:30, sometimes working on revisions at a real or DIY residency for a few weeks straight. I do these things for a time and then I have no interest in continuing and I find another way. I tend to write at my kitchen table. I’ve tried to not write at my kitchen table and it just doesn’t work.

I also always have a process journal near me—I write notes and ideas and draft things in there. I used to draft everything in there, but now I’m more likely to think via the process journal and type on my computer.

My goal was to be honest and to (as Chekhov advises) state the problem correctly. My job was not (as Chekhov advises) to solve the problem. In this way I tried very hard to write as honestly as I could in scene, without judgment. I wanted to be fair to the scene and to the people. That was the goal.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I’m a gardener. I have a huge urban garden (mainly vegetables, herbs, and berries) that I’ve been cultivating for over 20 years. I consider it part of my creative process. It’s also great to actually finish something: growing a carrot, for instance. It’s satisfying in a way that writing can rarely be, and it’s super important to my mental health.

I write songs, sing, and play the ukelele with friends. It’s probably the only pure hobby I have because I do write about gardening for publication. Playing music is the only time my creative brain shuts off. It’s so fun and we always have a giant potluck every time we get together, so it’s super social for me as well.

I’m also a big kayaker. I love paddling on lakes. It’s another time my brain gets to roam freely. It’s so calming and definitely helps erase the static that sometimes keeps me from making progress with my writing.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

Yes, I have a story collection coming out with Autumn House Press in April 2025. It’s titled I Have Not Considered Consequences and it has a lot of bears in it. Some pretty weird stories. I wrote a bunch of them during the pandemic. I’m also working on a nonfiction craft book with Ladette Randolph and Heather Lundine that should publish in 2026. The working title is No Regrets.

Thank you, I enjoyed this read and the snippets of advice re paying attention to both the creation and editing.