The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #9: Lucy Sante

"The truth is always more interesting than the stories we make up to disguise it. And as they say, the truth will set you free."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

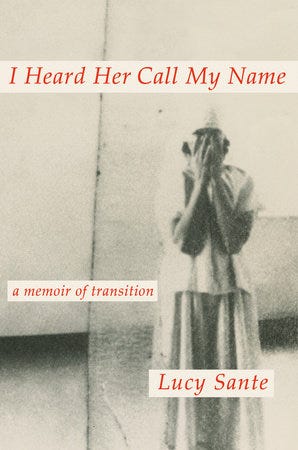

Here’s the ninth installment, featuring prolific author, critic, and artist Lucy Sante, whose most recent book is I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition. -Sari Botton

Lucy Sante is the author of ten books, most recently I Heard Her Call My Name. She has been a professional writer for over forty years, and wrote for many magazines when magazines still roamed the earth. She recently retired after 24 years teaching writing and the history of photography at Bard College.

--

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I'm, at this writing, a month from turning 70, and I've been writing since I was 10.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

I Heard Her Call My Name was published February 13, 2024.

What number book is this for you?

10 (more or less).

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

It's just a memoir.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book? (Up to one paragraph.)

My gender transition, and why I denied my gender identity for nearly 60 years.

My books are nonfiction and seemingly diverse, but they all have deep personal significance and none was a job of work. I've written about the places in my life: Low Life (about New York City), The Factory of Facts (about my Belgian birthplace), The Other Paris, and Nineteen Reservoirs (about the Catskills)…I Heard Her Call My Name is actually my second memoir, after The Factory of Facts.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

My fourth-grade teacher told me I had writing talent, and suddenly I wanted to be a writer. I also wanted to be an artist, but when I was 18 I decided to make writing the top choice. I was a poet, also wrote short stories, until I got a job at the New York Review of Books and began writing for them. I wrote for magazines for ten years before my first book.

My books are nonfiction and seemingly diverse, but they all have deep personal significance and none was a job of work. I've written about the places in my life: Low Life (about New York City), The Factory of Facts (about my Belgian birthplace), The Other Paris, and Nineteen Reservoirs (about the Catskills). I've also written three books on photography and published two collections of short pieces. I Heard Her Call My Name is actually my second memoir, after The Factory of Facts (according to a graduate student who interviewed me, I'm the only person to have written memoirs before and after transitioning).

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

It was the easiest and fastest writing I've ever done. It took about two months all told, while I wrote four significant essays on other subjects and did all the publicity for my previous book. There was absolutely nothing difficult about it, except stopping every night.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

That's an interesting question, because previously when I'd written autobiographical pieces I'd gone to great lengths to disguise my friends' identities. Realizing that that was part of the apparatus of denial I'd constructed to disguise my gender identity, I made it a point to be totally candid in this one. There are only four people whose names I don't use, which includes my two ex-wives, because my judgment of them is severe. I usually don't have anyone read my manuscripts before I submit them, but this time I had four people read it: three of its principals and a control.

Previously when I'd written autobiographical pieces I'd gone to great lengths to disguise my friends' identities. Realizing that that was part of the apparatus of denial I'd constructed to disguise my gender identity, I made it a point to be totally candid in this one. There are only four people whose names I don't use, which includes my two ex-wives, because my judgment of them is severe.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

I honestly didn't have any other writer in mind when I was writing this one. I did, though, recognize a certain music, a certain rhythm to the prose that felt familiar, and I eventually determined that I had unconsciously lifted it from The Madness of the Day by Maurice Blanchot, translated by Lydia Davis.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

The truth is always more interesting than the stories we make up to disguise it. And as they say, the truth will set you free.

What do you love about writing?

I became a writer as a direct result of learning English as a second language. As a child, I suddenly had a language that owed nothing to my parents. It was mine alone, this great synthetic entity with all its keys and pedals. When I was young I also wanted to paint, to make music, and to direct films, none of which I did—but which I do every day in my writing, all those operations transposed to the writing process.

What frustrates you about writing?

The fact that literature started going out of fashion even before I started on my career. It was vital as late as the 1960s, but now it is consumed by a thin minority and allows hardly anyone to make a living. Of course it was always mainly consumed by a thin minority, but that minority was culturally central; literature was aspirational, and it was a lure for someone like me, the child of working-class immigrants, neither of whom finished high school. If I were young today, from my circumstances, would it be my choice? Would it even be possible for someone with nothing to fall back on?

What about writing surprises you?

That I can routinely surprise myself. I figure things out by articulating them on the page—much better than I ever can in my head—and I never know where it will lead. It's endless entertainment provided I have a sufficiently chewy subject. And few sensations are as heady as when one is on a tear, the words seemingly being beamed in from somewhere else, the thoughts galloping across the page, the rhythms lithe and elastic.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

No, only deadlines.

I figure things out by articulating them on the page—much better than I ever can in my head—and I never know where it will lead. It's endless entertainment provided I have a sufficiently chewy subject. And few sensations are as heady as when one is on a tear, the words seemingly being beamed in from somewhere else, the thoughts galloping across the page, the rhythms lithe and elastic.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I still make collages—I had two gallery shows last year. Making collages is very much like writing poetry: suggesting meaning without ever spelling it out, building tension through juxtaposed ambiguities.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I'm working on the second of my two-book contract. It's about the Velvet Underground in their time, and of course it's about the band, but also represents the chance to write about New York City in the 1960s, something I've long wanted to do. After that I want to do a book about writing—a practical manual of sorts.

This interview is so enlightening and intellectually so close. Lucy Sante's sentiments as "the truth will set you free" or "I figure things out by articulate them on page--much better than I ever can in my head" are so true. They are also the postulates in my own memoir writing. And English as a second language... My English is still a second language, though it opened to me all the best literature, including Lydia Davis and Maurice Blanchot. Thank you for interview. Larisa Rimerman

This is amazing and such an important book. I'm ordering for a couple of people in my life with gratitude to the author for laying out an emotional map.