The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #106: Margaret Mandell

"Memoir universalizes, I think, when readers see their own vulnerabilities in the characters in the story."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

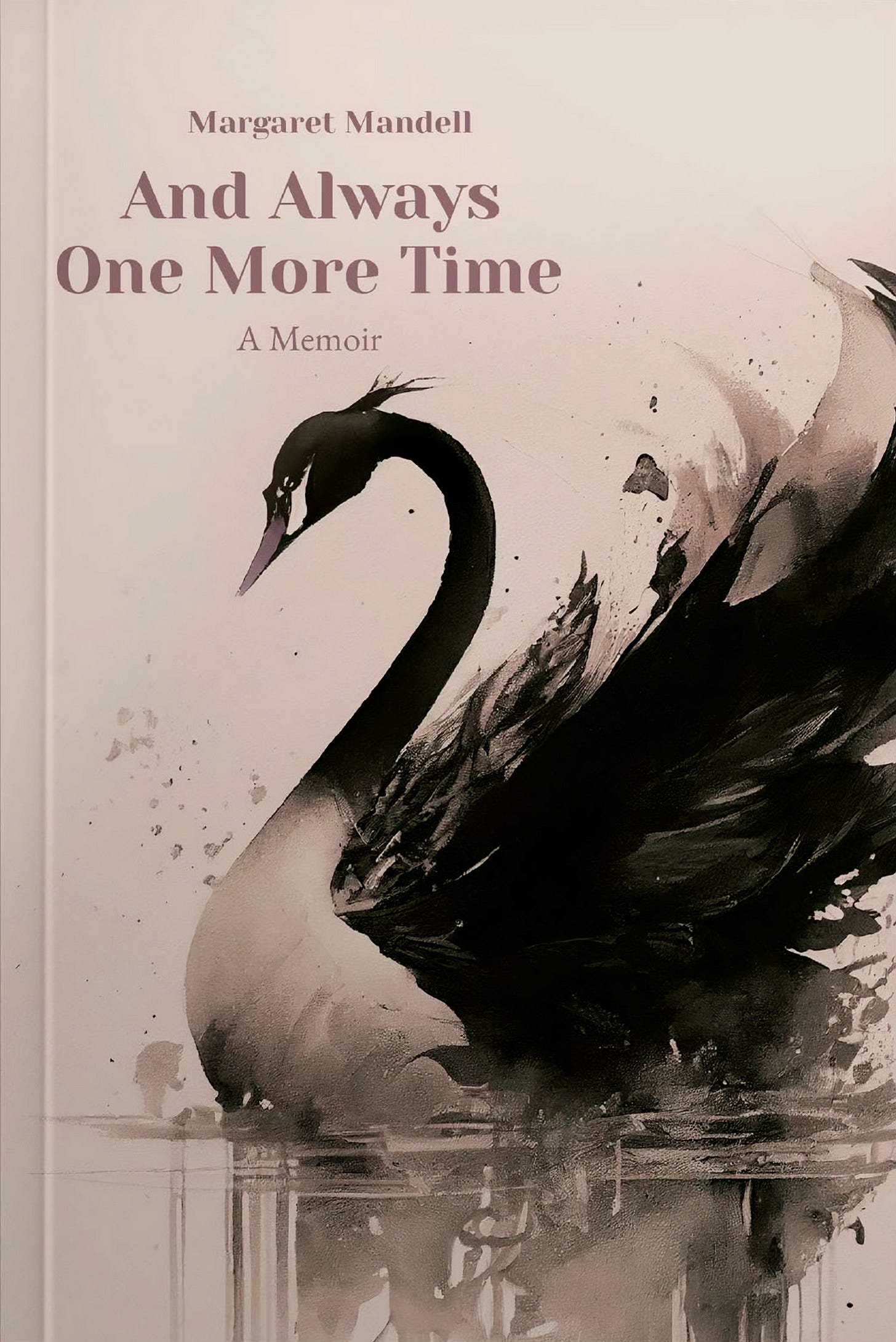

Here’s the 106th installment, featuring , author of And Always One More Time: A Memoir. -Sari Botton

P.S. Check out all the interviews in The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire series.

Margaret Mandell earned her BA, MA, and ABD in History at the University of Pennsylvania. She has been a doctoral candidate and college teacher, mother of two, executive recruiter and entrepreneur, independent school admissions director, triathlete, and certified yoga instructor. When her husband of many years passed away, she became a widow, a woman still in the midst of becoming. Her debut memoir And Always One More Time, released in March 2024 by Atmosphere Press, tells the story of her next act and new, sustaining love. Excerpts have appeared in The Metaworker, Brevity Blog, NextTribe, , Proseterity, and the Daring to Tell podcasts.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I am 74. I’ve been writing songs, poems, letters and lyrics all my life, and only recently have I embraced creative nonfiction. Because truth is stranger (and lovelier) than fiction.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

And Always One More Time: A Memoir, released on March 12, 2024, by Atmosphere Press

What number book is this for you?

Number one!

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

Decidedly memoir—partly epistolary, partly narrative prose. A selective looking back in the voice of the narrator through love letters to a deceased husband and twenty-one chapters of storytelling: an unfolding plot about having the courage to trust love one more time as an older widow through scenes, dialogue, reflection, and personal transformation.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

“The loss of a life partner strikes over one million new women every year—shattering the present, leaving the future in doubt. At 65 years old Margaret Mandell lost her husband of 45 years to a fast-moving disease. And Always One More Time poignantly captures that loss while making a winning case for unexpected wisdoms, new love, and a still dynamically unfolding self. Wise in the ways of C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed, suspenseful in the tradition of Joyce Carol Oates’s A Widow’s Story, and as universal in its truths as Steve Leder’s The Beauty of What Remains, And Always One More Time offers hope in the aftermath of greatest loss. At 35,000 potent and swift-moving words, it can be read in a single setting, much like George Saunders’s Congratulations, By the Way.”

If you are reading this, it is because I just wrote a book. My first in 74 years. I wrote it because my husband died. Like all deaths of loved ones, the loss left me flailing, incapable of imagining life without him, unable to let him go. So, I began writing to him. Every morning. For years. Like Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking, I believed he was still there.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

The Making of a Writer: One Letter at a Time

Let me begin at the end.

If you are reading this, it is because I just wrote a book. My first in 74 years. I wrote it because my husband died. Like all deaths of loved ones, the loss left me flailing, incapable of imagining life without him, unable to let him go. So, I began writing to him. Every morning. For years. Like Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking, I believed he was still there. Writing is one way of turning horror into redemption, denial into acceptance. I was writing to my husband to hold onto him but also to honor him, in the end discovering that love is being your best self in the presence of another: that keeping him alive on the page was a profound act of love. Moreover, loving another and writing about him, too, freed me to continue my aspirational journey to be my best self in the presence of another.

But how did I become a writer in the first place?

I am the eldest child and only daughter of a reading specialist and an inveterate salesman. She loved great literature, and he understood the power of words to seduce and persuade. By fourth grade I was churning out stories hatched in my imagination and filling my diaries with entries fascinating only to me. “Your daughter is a writer,” the teacher told my mother.

At age 12, my first summer away from my family, nervous and homesick, I wrote daily detailed letters to my parents, chronicling my every activity at summer camp. Letter-writing became the antidote to separation anxiety. Miss somebody? Write a letter!

My third year at camp I became the Jungle Jingler, assigned to write rhyming jingles about life at camp. Jungle was the name of my bunk—what else could they call a cabin full of hormone-cursed 14-year-old girls just getting their periods? Including me. The day I ran sobbing into the infirmary asking for a Kotex you can be sure my parents got an extra letter in clinical, painstaking detail—especially the one to my mother, marked confidential--whereas the one to my father referred cagily to “my time of the month.” That’s what men called it.

In graduate school at Penn, I began hiding behind five-syllable words and rarely, to the chagrin of my professors, used anything shorter. But I also understood by then that the power of words and the power of cogent thought were mutually reinforcing. I had mastered synthetic reasoning and used it effectively in my writing about Modern European History. I thought I was becoming a scholar, destined for the halls of academe.

I had also fallen head over heels in love with an aspiring medical student, not yet my husband, and when I traveled to France alone to pursue graduate study during the summer of 1973, my letter-writing to my future husband surpassed anything I wrote at summer camp in length, frequency, and unremitting detail. I had to use air mail paper, like writing on a tissue. Herb would propose to me by the end of the summer. Was it the letters?

Eventually I landed back at Springside School, my alma mater, for a twenty-year stint as Director of Admission, where I could be both my mother and father: an educator and a salesman. The work suited me perfectly because there were admission acceptance letters to write. Heart-rending, truth-telling letters to parents of three-year-olds persuading them to choose Springside School for the next fourteen years in a crowded field of expensive elite private schools in Philadelphia. Letters in which the child was seen, valued, and well-matched to a rigorous college preparatory curriculum. A brilliant teacher and colleague taught me to observe the children so closely during their visits that I discovered a profound truth about writing: great writing begins with great seeing.

By the end of my career, I’d written thousands of letters. It wasn’t just that the children enrolled in the school. It was that the parents saved my letters and trotted them out years later to show me that almost everything I foretold came true. A three-year-old’s play preference, such as being drawn to a stethoscope, ropes, and pulleys, often led to a lifelong interest in medicine, physics or engineering. A child who displayed empathy when another child cried would remain emotionally intelligent into adulthood, finding her way into mental health or pastoral care. Emotional forecasting was part of my work, and it was authenticated in the letters—another kind of love letter, it turned out.

But it was the untimely and tragic death of my husband that would unleash my passion for letter-writing as never before. Every day after he died could not begin without a fulsome letter as I filled book after book after book, tears marring the ink on the page, until one day I thought, I really am a writer. It happened when I realized my letters were no longer just for my husband but would become a narrative that grappled with universal questions about loss, aging, resilience and trust—even motherhood.

And Always One More Time is my new beginning.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

I had no idea how hard either would be. Humility, persistence, and embracing steep learning curves in uncharted terrain got me there.

Writing. Pushed by two exacting writing coaches, I had to learn that my raw material, that beloved first draft, those 1,000 letters, were lightyears away from a completed memoir. Revision is an accordion in constant play—contracting, expanding, adding, taking away. Tedious, plodding work, aiming towards a narrative arc, a moving target that materializes over time. For me it was four years of revision after transcribing the handwritten letters into electronic form—word surgery, exercising my brevity muscle (“Nope, nope, nope,” she said; “Go deeper, go broader,” she said). After the book was out in the world, readers wrote, “Packs a punch.” “Not a wasted word.” “Left me wanting more but fully satisfied.” Only then did I appreciate the power and necessity of all that revision and the wisdom of my coaches.

Publishing. Researching publishers (traditional and hybrid), pitching my manuscript to several agents, I finally submitted my manuscript to the hybrid publisher, Atmosphere Press, and never looked back. As a first-time unknown author, I knew I had to do all the work including writing book adjacent essays for online publications—a different genre, learning as I went along, meeting more exacting editors, such as Sari Botton. Soliciting reviews from Kirkus, BookLife, IndieReader. Finding an audiobook producer so I could record the book in my own voice for Audible—an arduous, unexpectedly long task in itself. A performance. The work of promotion called upon entirely different skills. Such as creating a professional website and social media presence from scratch. Developing a contact database and composing monthly newsletters to them. Pounding the pavement calling upon bookstores and libraries; scheduling talks, interviews, and podcasts. Saying “yes” to every opportunity. Nothing fuels persistence more than wanting it so badly you can taste it. After Herb died, I conjured the film “Out of Africa”: once I had a man; he was not mine; he was never mine. So, too, with the book: once it is out in the world, it is not mine; it was never mine. Publishing is letting go.

Writing is one way of turning horror into redemption, denial into acceptance. I was writing to my husband to hold onto him but also to honor him, in the end discovering that love is being your best self in the presence of another: that keeping him alive on the page was a profound act of love. Moreover, loving another and writing about him, too, freed me to continue my aspirational journey to be my best self in the presence of another.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

And Always One More Time honors two men, one living and one dead—John and Herb. John was given right of first refusal for every word. He requested plenty of deletions and I respected each one, pushing back on a few. After all, John wrote on the dating website where we met, “What makes me laugh? Life’s inevitable humiliations!” This man can laugh at himself. So, too, with my children—Dan and Lydia—including how I portrayed their father and grandmother, both now dead. First, do no harm.

My book is not a book of grievance or revenge. But it is about vulnerability: Herb’s, John’s, my mother’s, my children’s, and above all, mine. Memoir universalizes, I think, when readers see their own vulnerabilities in the characters in the story. It was a supreme act of generosity that the real people in my life gave me a wide berth in exposing their frailties, perhaps because I modeled my own unvarnished self-disclosure. We are all terrified. Why pretend otherwise?

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

I shall name my top three, each of whose whole body of work inspires me.

Margaret Renkl

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

How badly do you want to write your best book? Not someone else’s, yours. Pretend, as I did, when you write your first draft, no one will ever see it. The first draft is for you; all future drafts are for others. Find the best mentors you can and be willing to find new ones. Then listen to them. Just when you’re ready to quit and give up (everyone hits that wall), dig deep. Give it all you’ve got. Submit an excerpt you’re proud of to lit mags—in a sea of rejections (get used to it), it only takes one acceptance to believe in yourself as a writer. Keep going. The rewards are beyond rich.

What do you love about writing?

We write to know what we think. We write to see more clearly, think more deeply, experience all the sensations of life more fully. Above all, to connect with others, to give to them, to leave a piece of ourselves behind after we’ve departed this earth. What’s not to love?

What frustrates you about writing?

When I’ve written something and I ask, “So what?” Or when I’ve poured out my deepest yearnings onto the page and someone still asks, “So what?” When the words just won’t come (my therapist says we are not silent because we have nothing to say; we are silent because we have so much to say). My worst enemy is my impatience.

What about writing surprises you?

How thoughts can materialize out of thin air. Truth, too.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

Morning, morning, always in the morning. Every day creation is renewed.

Pretend, as I did, when you write your first draft, no one will ever see it. The first draft is for you; all future drafts are for others. Find the best mentors you can and be willing to find new ones. Then listen to them. Just when you’re ready to quit and give up (everyone hits that wall), dig deep. Give it all you’ve got. Submit an excerpt you’re proud of to lit mags—in a sea of rejections (get used to it), it only takes one acceptance to believe in yourself as a writer. Keep going. The rewards are beyond rich.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

As a yoga teacher, I write themes for every class and weave these themes into my teaching, which is an interactive conversation with other peoples’ bodies. First, I frame the practice, then I elaborate while modeling poses for my students, coming to a bit of a climax, then working towards a grand conclusion. More than just exercise, my students love the evocative, dramatic storytelling. All 90 of the classes I taught in the past year and my one-paragraph descriptions are archived at burnalong. This online fitness platform allows me to create original content and store it permanently for on-demand access. Taken in its entirety, it could be a textbook that illustrates how to combine the craft of writing with the physical practice of yoga. It is joyful, challenging work.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

As I write this, I am in Merida, Mexico (capital of the Yucatan) where I just gave a reading and book talk at the Merida English Library

I’ve been on book tour for the past year and am scheduled through May 2025, but this was my first author event outside the United States. Promoting and fulfilling commitments for And Always One More Time has consumed all my creative energy for now. Every review, every author event, every encounter with another reader teaches me something new, and humbles and uplifts me beyond my wildest expectations.

But I shall write again.

Peggy! Here you are, in Sari's fabulous Oldster, where you belong. Many congratulations on taking this book all around the world. (And can't wait to join your book club later this summer.)

Excellent strategy. My library uses Libby-- and I just found your book there. Yay! Readers should be sure to ask their local libraries for titles of books they'd like to listen to but that aren't (yet) available. It supports all your favorite (and especially independent) writers.