The Re-Parent Trap

Boo Trundle recalls her bumpy road and resistance toward "inner child work."

My friend Tanja was having ice cream and cookies with her imaginary inner child. She wanted me to try inner child work, too. Tanja said it helped her quit drinking and establish what she called emotional sobriety. That sounded fantastic to me. But I had no interest in cuddling with a make-believe reincarnation of my former self. I was 25, a self-styled hell raiser. I wore a zippered leather motorcycle jacket and I cut my own hair. I had no time for self-love.

Since Tanja was helping me get off drugs and booze, she offered other helpful strategies. Today we might call them life hacks. For example, wear stockings under your jeans when the temperature dips below 20 degrees. Take a hot bubble bath when you feel depressed, or stressed, or for no reason at all. Carry a pocket of hard candy to a party. That way you can suck on a piece if the booze tempts you. Avoid the guy who takes Molly and swings around your apartment impersonating a baboon. Lose his number!

Tanja had named her inner child Clara. She talked about Clara in the third person all the time.

“Clara wants to go to the movies today.”

“I need to check with Clara before I make plans.”

“Clara wants Atomic Fireballs.”

“Clara only rides the long bus with an accordion in the middle.”

I didn’t like Clara. I wanted her to go away, or at least shut up. Tanja’s inner-child experimentation struck me as esoteric and fringe. She had just moved to New York City from Los Angeles, and, you know, CALIFORNIA.

I was 25, a self-styled hell raiser. I wore a zippered leather motorcycle jacket and I cut my own hair. I had no time for self-love.

Tanja’s objective was to nurture and support, or symbolically re-parent, her inner child Clara. Tanja’s actual parents had failed miserably at this, as had mine. But I wanted nothing to do with my inner child. Deep down, I must have suspected she’d be a burden, or a miniature menace worthy of a David Cronenberg film. (see, The Brood.)

“Fine,” said Tanja. “You don’t have to do inner child work.”

Then she tricked me into doing it anyway. She told me to write my life story, which would hopefully shed light on the reasons I drank too much. When I finished writing, I was going to read this mess aloud to her. This exercise was part of the group’s recovery program. I found out later that hers wasn’t the orthodox approach, which entails making a list of enemies and resentments. Tanja was my sponsor in the program, though, and this was how she did it. So I filled a spiral notebook with my tales of woe. And I made an appointment to share it with her.

We met at her Upper East Side sublet, which, she explained, she couldn’t afford. It was a studio apartment: dark, lamplit, minimally furnished. Her things were already boxed up for her next move. We perched on the edge of her bed because there was nowhere else to sit. Out came the childhood chronicles, and I began to read. As I read, Tanja asked questions and made observations. My back ached. My head hurt. My stomach growled. It took over three hours.

Tanja must have been suspicious, or at least a little bored, because most of the events I shared with her took place at the Princess Anne Country Club pool. I just had to get this stuff off my chest. There were snack-bar betrayals: a popular boy took a rejected girl’s sandwich apart when she wasn’t looking. He spat inside it, then gave it back to her to eat. I didn’t warn her. Also, near-death experiences: I pushed a younger kid into the pool during her swim lesson, forgetting that she didn’t know how to swim. Basic embarrassments: I fainted during a tennis lesson and peed in my pants. And then there was that thing with Bud Wells the summer after fifth grade.

“We rule! You suck!” I scrawled in huge, looping letters, with bright red chalk, right there on the pavement at the opposing team’s swim club. When the meet was over, my swim coach sat the whole team down on the pavement near the graffiti. He was a shouting grouch with red hair and a bushy mustache. He was built like a truck and always very sunburned.

“Who did this?”

I didn’t raise my hand. Bud Wells would beat me up if I told. It was his idea to write on the pavement. I didn’t think up stuff like that. But I did help him do it. I was wandering around in a dream. In this drifty condition, I often stumbled into bad behavior, which got me into trouble with adults.

“Is this why you became a drunk?” Tanja asked, interrupting me. “Was it the pull of the dream? Or maybe remorse and shame over these bad things you did? Maybe it was worse because you didn’t know why you did them in the first place.”

I stared at her. I didn’t have answers. I just wanted to get to the end of my notebook. I looked down and continued to read.

The coach presented us with a “fess-up-for-your-honor” scenario, I told her.

“We’re not leaving,” he announced, “until the person who did this comes forward.”

Tanja’s objective was to nurture and support, or symbolically re-parent, her inner child Clara. Tanja’s actual parents had failed miserably at this, as had mine. But I wanted nothing to do with my inner child. Deep down, I must have suspected she’d be a burden, or a miniature menace worthy of a David Cronenberg film.

I sat there and sat there. All the kids looked around at each other. The coach waited. I did not confess. The coach threatened to punish the whole team with extra practices and restricted snack-bar access. Bud, sitting near me, cross-legged in his tight speedo, gave me a reptilian warning with his green eyes. There was no way I was going to give myself up.

I see the confused child that I was, the skinny girl by the pool, becoming unmoored, turning into a human hot-air balloon. Bud handed her the red chalk and said, “Write this on the pavement.” The pavement was hot. She stopped thinking. She wasn’t thinking.

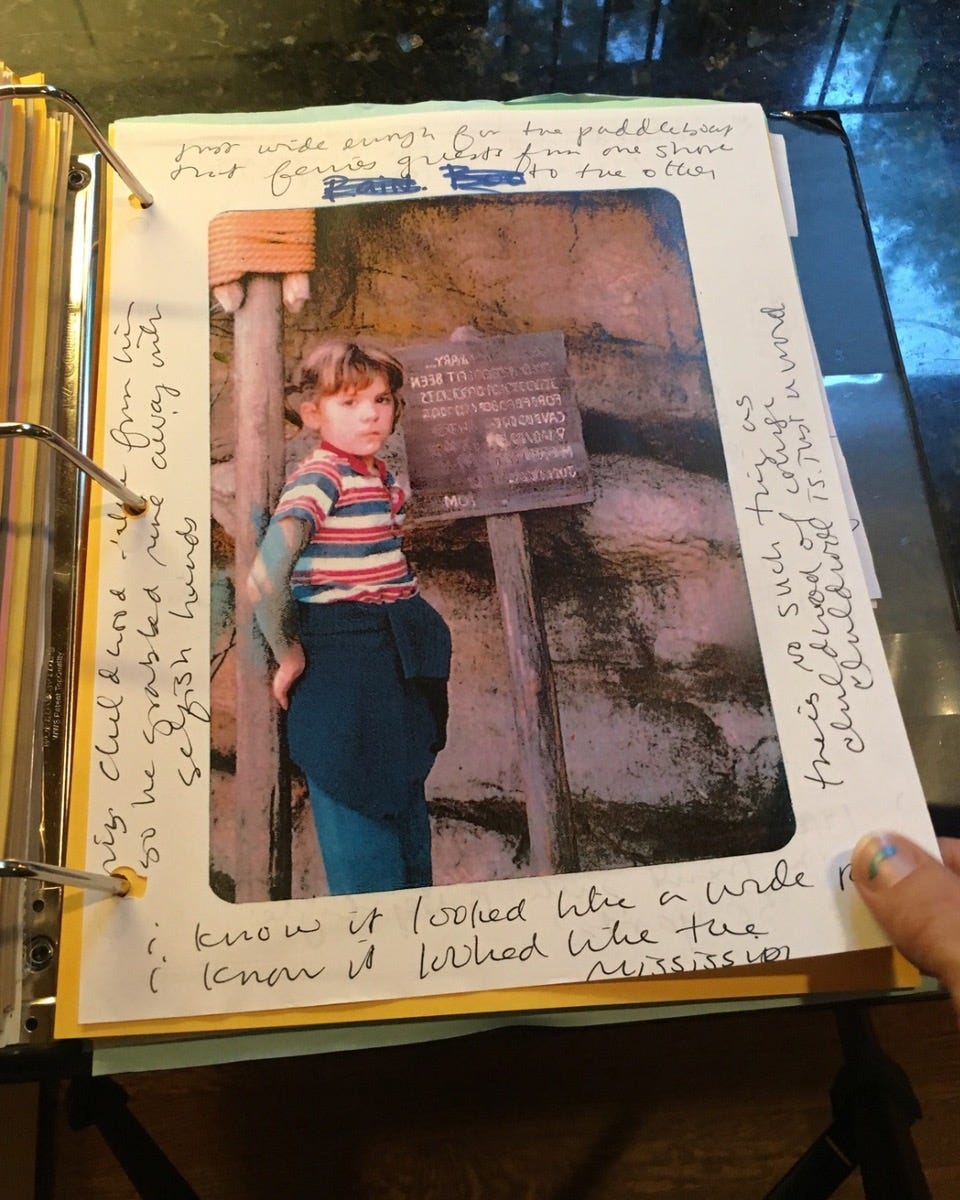

This easily coerced girl is my inner child. She wears that green-and-white striped bathing suit every single day of the summer. She’s sun-kissed, tan. She has short brown hair. When I say that Tanja tricked me, I mean that by writing about these incidents, I did, in effect, bring my inner child to life. But that was all. I didn’t say hi. I certainly didn’t offer to give her a hug. I wouldn’t be ready for that until many years later. My afternoon with Tanja was only a first stab at getting honest about the past. There was a lot more to look at than tennis and swimming.

When I was in my 40s and my marriage of two decades was falling apart, I found a therapist who specialized in inner child work. I didn’t know this when I started with him, but it was a professional passion. He urged me to find a young version of me. He claimed she was waiting inside, desperate to be discovered. I was willing to try almost anything to save my marriage, but my old resistance was still there.

Or maybe it was a new resistance. The first time around, when Tanja introduced me to Clara, I dismissed her as goofy and New-Age. This time, I had doubts about my own ability to succeed. No one is safer for your inner child, the thinking goes, than the adult you. I wanted this to be true, but I was scared it would not be. What if I let this child down, after she waited all those years?

My therapist persuaded me to try. Our first step was to create a safe inner space, like a cozy living room in the center of my soul, where we could introduce my adult self to my inner child. It took several months of guided meditations for me to seal off a space in my head. If I imagined myself on a white beach with blue water, my then-husband would come strolling over the dunes. If I imagined myself on a country road in a flowery meadow, he’d come crashing through the field on a tractor. I finally settled on a one-person spaceship, a tiny pod attached by a thin cord to a station floating just outside of Earth’s orbit. That’s how far I had to go to feel like I could get some privacy. Even after I left the earth’s atmosphere, I sometimes saw my ex-husband outside the pod in a little spacesuit, like George Clooney in Gravity, peering in through the window. But eventually, I pulled the plug, and I was alone out there.

When I say that Tanja tricked me, I mean that by writing about these incidents, I did, in effect, bring my inner child to life. But that was all. I didn’t say hi. I certainly didn’t offer to give her a hug. I wouldn’t be ready for that until many years later. My afternoon with Tanja was only a first stab at getting honest about the past.

Once we had a safe space in which to meet her, my therapist and I made initial contact with my inner child. But I had no idea what to do with her. It was enough, at first, to bask in the feeling of safety we had created, even if only in my imagination. A hard-won familiarity with that feeling led me to realize I was never going to feel safe in my marriage, and my husband and I made the painful decision to divorce. This was just the very beginning of my journey with my inner child. So don’t try this at home.

Luckily, you don’t have to. There are several different support groups that focus on inner child healing. My therapist was solid, even brilliant, but my deepest healing has come from working with what recovering people call “fellow travelers.” In other words, each other.

We went on retreats and weekend gatherings where we held hands (symbolically and sometimes literally) and traveled into the past together. We did things like playing a modified version of musical chairs called “Shame Busters.” We used crayons to scrawl letters from our child selves with our non-dominant hands. We cuddled with giant, stuffed teddy bears. If you google “life-sized teddy bear,” you’ll see how big they can get. Some of us need a lot of plush and cuddling.

Human beings cling stubbornly to the notion that time is linear, moving forward toward the future. But emotional timelines are perfectly reversible, stretchy, bendy, and wild. We file psychological events away in our subconscious. Trivial or pivotal, these pictures and images are intangible and often invisible. Childhood memories morph into emotional habits and inexplicable attractions, tendencies, moods. The simple act of intentional recall, then getting what we remember down on paper… this is a form of time travel. Once you’ve created your time machine and traveled into the past, it’s up to you. Will you soothe, comfort, care for, coddle, connect, talk to, protect, and love your younger self?

Once we had a safe space in which to meet her, my therapist and I made initial contact with my inner child. But I had no idea what to do with her. It was enough, at first, to bask in the feeling of safety we had created, even if only in my imagination.

The newly sober me, that tough chick in the leather jacket with the crooked bangs, had no time for reparenting. She called it wishful thinking, science fiction. The current me, sitting in my sunny home office, typing this out… let’s take a quick snapshot: healthy mother of beautiful teenagers, sober, stable, awake, busy living her fifties. Still here.

Inner child adventures? I say yes, absolutely. I’ve created an entirely new, parallel timeline, and two new selves. The original child has been introduced, over and over, to a caring adult version of me. And the adult me who goes back, when she can, to retroactively nurture that child, also changes. Reparenting results in a different adult, one who grew up in that improved version of the past. The alternate child version of me thrives in the light of that intervention. On many days, our good days, we’re all in a very safe place. Together.