The Rebellious Act of Stillness

Migrating from Nigeria to Holland and back again to attend boarding school, a young girl searches for the true meaning of home.

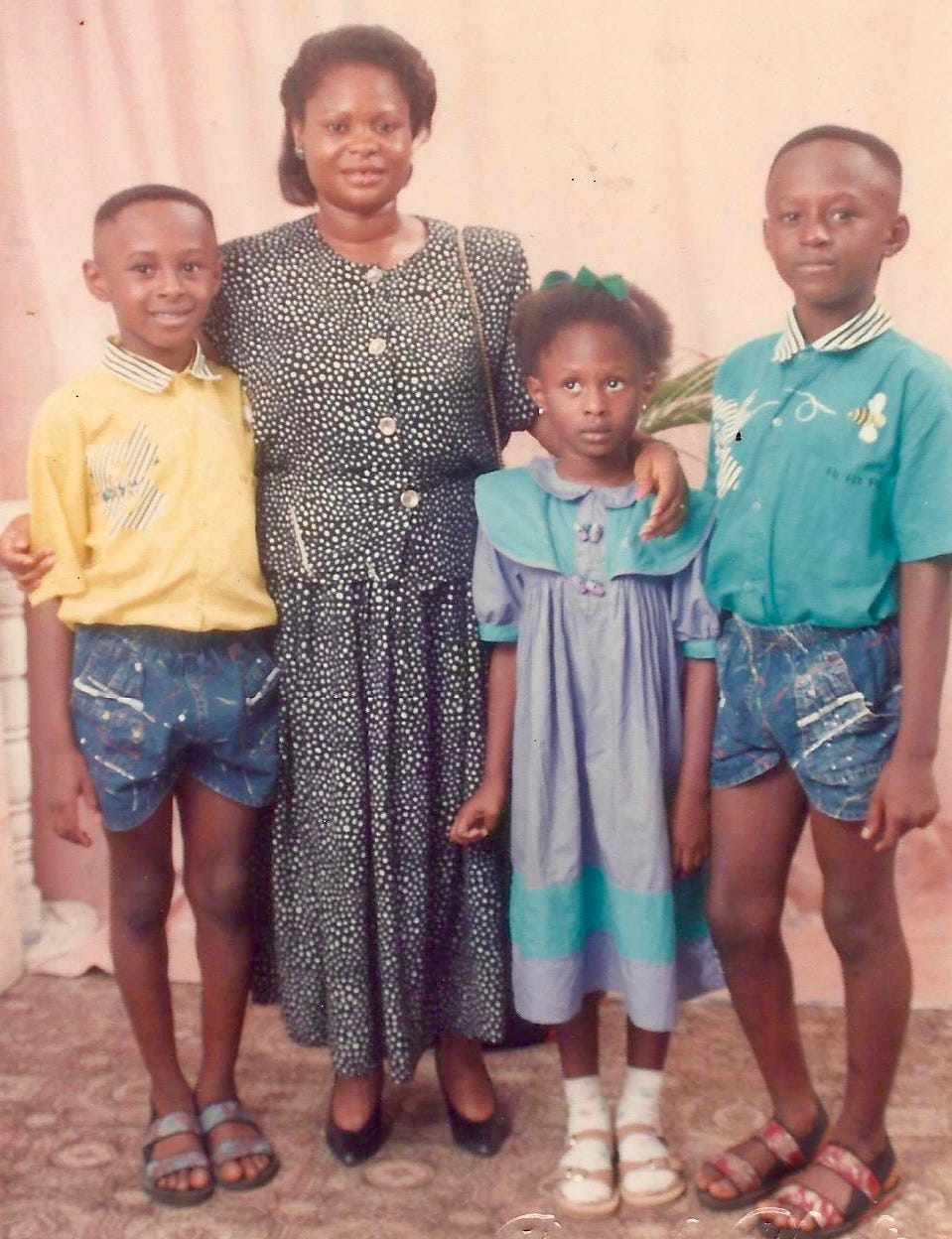

In Nigeria, I was the baby running behind my big brothers, climbing trees, sometimes jumping out of them, and showing my mom my bloodied knees so she could clean them with cotton wool and wipe my tears with her palms.

Our house was full, always full, of doting aunties who drank Guinness straight from the bottle sometimes mixed with a cold Coke; laid-back uncles whose laughter shook the walls; and other kids from our neighborhood in the Shell Residential Area who, like the boys and me, seemed only to be interested in how high any of us could climb the trees in our yard. And joy – the kind that hummed under our feet and sat down with us at meals. And kisses, which we planted on each other’s cheeks before bed.

Between teaching high school physics and running our household, my mom was as busy as a hummingbird but still found time to tuck me between her knees on weekends and thread my hair into plaits. On weekends when her hands were too full with errands, she would bring me to her salon down the street and leave me in her trusted hairdresser’s chair with a packet of plantain chips while she ran around town.

I was inherently restless, full of questions, annoyed by silence, and easily tempted into misadventures that tore holes into peace and logic. For example, in an inexplicable series of events, I pressed my cheek against the face of a hot iron at the beginning of one week and, by the end of that week, I returned to that hot iron and kissed it.

I was a cloud watcher. Even before I entered the sky for the first time, I watched it from the ground, traced its many changing faces, and counted the things it brought and took away. Seasons, birds, clouds wrapped in electricity, and a dull but very present longing to grasp onto what would always be fleeting, what was never meant to stay.

I was inherently restless, full of questions, annoyed by silence, and easily tempted into misadventures that tore holes into peace and logic. For example, in an inexplicable series of events, I pressed my cheek against the face of a hot iron at the beginning of one week and, by the end of that week, I returned to that hot iron and kissed it.

When gleaming white cattle egrets arrived in a hazy December sky in Port Harcourt City like swatches of white paint streaked along the crests of cirrus clouds, drifting into our world like cotton, my brothers Obi, Ik, and I welcomed the migrant birds in the garden with song while they cut across the topaz sky fresh from the north. For creatures whose lives were so tied to the continuous rhythm of taking flight and leaving places (and, inevitably, parts of themselves) behind, there is a stillness about them as they stroll across lawns, peck at insects, or simply sit. We’d shine our fingernails at them, flap our hands, and belt: Chekeleke, give me one better finger! Breathlessly, we checked our hands to see if chekeleke – the egrets – brought us gifts from their arid home down to our forest-filled south. Days later, I’d find tiny cumulous clouds floating on the pink pads of my fingernails, as white as an egret's feather. Then, usually, as the first torrents of the rainy season thundered in, we’d look out at grey clouds pregnant with a new season and realize the absence of the white specks that dotted the green landscape. A small grief set in when it dawned on us that at some point, without warning or ceremony, they’d gathered up their feathery things and their ivory luck, and flown away.

***

There was little ceremony as my family was swept into preparations to leave home. My mom was the messenger: Papa was being cross-posted to the Netherlands for an extended project with Shell for a few years, so we would go with him. We would enter the sky, cross the Mediterranean Sea, and nestle into a quaint Dutch city called Assen.

On our last night in Nigeria, I tip-toed to the window in the middle of the night, heart fluttering, imagining our new life in a new country while Port Harcourt, now an ocean of darkness punctured by a thousand pinpricks of light, winked its goodbyes. I felt ready, open, restless – like I could climb out of that window and fly directly into our future. When I turned to slink back to bed, my mom – a remarkably light sleeper – was already propped up on her elbow. “Ada Baby, why are you awake?” she whispered groggily, sort of irritated. “Go back to bed. We’re leaving early.”

I still wonder if she was as excited as I was about our new chapter. Or if she knew that migration and transition are fraught with dissonance – some of it is harrowing, parts of you die or fall off like feathers, even as you watch new and beautiful things hatch into your life.

Holland was new in a way I couldn’t have imagined. Flat, severely organized, but still pretty especially when it wasn’t drizzling. There were neat lanes and traffic lights for pedestrians, cars, and bicycles. We discovered new delights: sugar-dusted olie bollen that stuck to the roof of my mouth. Vibrant tulip fields. Autumn, winter, and snow. Quiet, sweet-smelling summers. Bike rides past canals and windmills. And trying new food from the many cultures of other expat kids at school. These things were easy.

But for the first time in my little life, with my brown skin and fluffy black hair, I looked different from most people around me. So, Holland also began pecking at my soft outer shell almost immediately. Someone once asked me if it had to do with the Dutch tradition of Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet. But as a kid, they were merely part of a joyful and festive foreign Christmas tradition I was learning. Had I been a bit older, maybe I would have noticed that the person playing Zwarte Piete (“Black Peter” who, in the folktales, was a demon St. Nicholas conquered and forced into enslavement), was a white person painted black with overdrawn bright red lips, always wore an afro wig, and behaved buffoonishly. Maybe I would have asked someone why the manifestation of a demon condemned to serve his white conqueror was fashioned to look like a bad cartoon of a Black person with hair that looked like mine. At the time, I wouldn’t have named Sinterklaas as the culprit. Instead, it was a constellation of other hard-to-name, hard-to-pin-down occurrences: my white classmates seeing themselves in the books we read and movies we watched, while I was nowhere to be found; a friend’s mom cornering me during recess and, with her white face scrunched while pinching and inspecting one of my plaits, interrogating in her thick German accent as to whether it was my real hair; white grownups and their children at the supermarket stopping and staring at us like they were witnessing creatures of the dark part of night walking around freely, buying ham and cheese as if we were normal.

This feeling clashed with the love I found at home, the tenderness of still being called “Baby.” It felt like being torn in two: one half of me was familiar and I knew her, the other half was a stranger created by someone else’s gaze. Two halves squeezed uncomfortably inside my body and tangled with one another, shoving, yanking, dragging each other. I grew agitated by that anxious sense that I was wrong – not what I did, or what I thought was wrong, but that my very existence needed to be tamed, conquered, and fixed. I hated that ache, like stretching bones, as my body and spirit made room for the breadth of other names I would bear in the world – Black, alien. I chased kids who hissed that my hair looked like worms, wrestled them down, and had to explain to my mom why my stockings were ripped again. I learned that if I wanted the teachers to be sweet to me and understand me when I recounted why I shoved those kids, I had to bend my tongue and melt my harsh Nigerian accent to sound like the boys and girls from Europe and America. I became an ironsmith, liquifying and recasting my accent into something rounder, into what I was learning was prettier.

On our last night in Nigeria, I tip-toed to the window in the middle of the night, heart fluttering, imagining our new life in a new country while Port Harcourt, now an ocean of darkness punctured by a thousand pinpricks of light, winked its goodbyes.

My name was impossible to carry in the mouths I found in Holland. Too many vowels mashed together frustrated my teachers’ and classmates’ tongues which were accustomed to plainer flavors. My parents hadn’t prepared me for the possibility that my name would be continuously mutilated here and that it would hurt. But they were learning these things for themselves, as the musical curvatures of their names were also hammered and flattened into benign slabs. And yet, the evening I asked my dad for an “easier” name like Sarah, he sat up in his Chesterfield rocking chair, a thick novel lying open in his lap, and said firmly, “No. That’s your name. We’re not changing it.” As if to say, Don’t run away. This is where you are meant to be, and there are good things here.

My parents, both survivors of war, understood this dance. They knew resistance wasn’t only in fighting back – it was also in rooting down. Our names were our proclamations and our refuge, affirmations in our language that we come from people, and that we are people. When anyone anywhere called me Adaeze, they would have called my whole family royalty through their own lips, even if their mouths didn’t know how to carry the ancient shapes of our language.

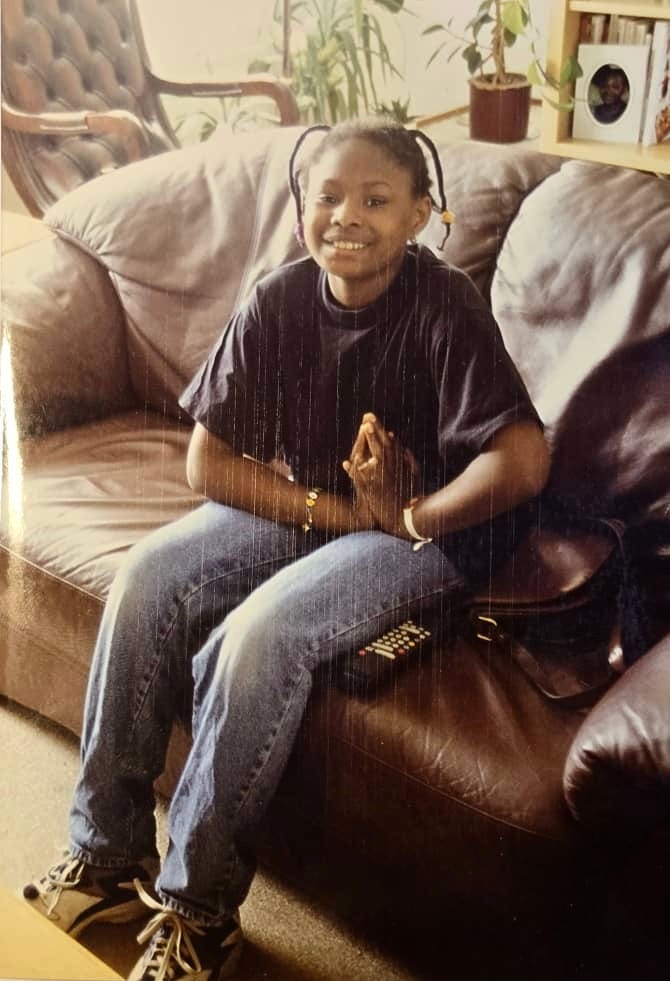

My mom’s resistance was displayed through living monuments she created on my head, which we changed out every Saturday. Without a work visa in Holland, she was suddenly a housewife with more time on her hands than in Nigeria. And since there weren’t any hairdressers for our kind of hair in Assen, she turned her bathroom and bedroom into a salon for two. No relaxers to melt my coils into submission despite my begging. Instead, she would scrub my hair with jojoba shampoo, letting the warm water wash over my soft black halo, like anointing, flushing away my heart’s bruises with last week’s dandruff. Then she would bind my hair with thin black thread, constructing sculptures like exposed tree roots along my crown.

Every week, as she freed, washed, and re-bound my hair in the private quiet of her bathroom, she salved my wounds, my confusion, and restless agitation, and tethered us both to Home. Each movement into stillness, staying put against the urge to bend ourselves or run away from who we were, made room for us to hold the duality of our transition.

We sang our alsjebliefts and dank u wels at the Dutch shops and playfully to each other at the house, my mom filled our home with Delftware and wooden Nigerian figurines that looked like little gods, and our garden was radiant with tulips. We summered in Paris and Oslo and London to look at cathedrals and fjords and famous bridges. We were immersed in our international expat community who’d flown in from every corner of the world and were engaged in their private dances of shedding old selves and welcoming new ones.

We did these things even after a faction of Dutch men at work confronted my dad, indignant that he (a foreigner) was promoted instead of one of them (a Dutch man). As though he hadn't earned it, as though they hadn't noticed that he gave them and their work most of his waking hours. We opened ourselves to the beauty of our new life even as my mom began stopping in her tracks to stare back at the hostile white gazers; even when my dad scolded a restaurant host for not seating us for nearly an hour while she welcomed other non-Black families who arrived after us; and even after my mom and I found that globule of spit, like a tiny jellyfish, sliding down the side of our car in our driveway. When she kissed her teeth and muttered, “Those stupid children,” I wondered what else she’d already endured at their hands.

***

My parents didn’t tell me that when you leave home when you’re five years old, you can’t really go back. You may not have felt it happening, but you changed in your years away. Some parts of you won’t return, some parts shrank away to make room for new parts that are hungrily pushing into the world.

I returned to Nigeria differently – eleven years old, shier, moving through the world like I now knew pain and was averse to it. My sanded-down accent and my sensitivity made my extended family and friends step back. Without knowing what to do with this version of me who was taller, taciturn, and British-sounding, they simply called me oyinbo and béké, meaning white. They said it playfully, endearingly. Sometimes they replaced “Ada-Baby” with “Ada-béké as a compliment because to them I was now something exotic, a bewildering amalgamation of the deeply familiar and the completely foreign. It made me wince.

But underneath everything, I was still hungry for the world. I was hungry for belonging and enough freedom to give myself a name of my own.

***

There is a season on campus at Adesoye College, Offa, one of Nigeria’s most elite secondary schools, when the giant cottonwood tree behind the wood workshop begins to puff out small clouds of cotton from its branches. It is lovely for a few days, the tree and its head of white hair. Then a wind descends that steals the loosely-formed orbs from the tree and spreads them across the classroom area like cotton candy floating through the air. White fog perches over campus in the mornings hindering our ability to see into the distance before the sun rises fully and melts the fog away, revealing another lighter haze of dust blown in from the Sahara desert.

The Adesoye College slogans, God the Almighty and A Quest for Excellence, had wafted to the Netherlands and planted into my mom’s ears. The school set out to produce Nigeria’s next generation of leaders out of children who mostly lived in comfort’s lap. ACO students were to continue our parents’ towering educational and occupational legacies. ACO parents understood that this couldn’t be achieved if their offspring were spoiled, and many of them didn’t know how not to spoil us, so they pushed us out to the school when we were 10, 11, 12 years old, to be educated, trained, and toughened for six years.

In the year 2000, everything seemed precarious and in flux. Nigeria was a newly minted democracy after decades of military dictatorship under a handful of corrupt and violent juntas. We were transitioning as a nation, as we students at ACO seemed to be in a constant state of movement: lights-on, chores, inspection, morning tea, classes, breakfast, more classes, “siesta” (during which we hand-washed our clothes), classes again, dinner, homework period, evening tea, lights-out. Repeat for six years – without our families except for three visitation afternoons per semester (most of which my parents couldn’t make because Port Harcourt was so far away from Offa), and with achy homesick hearts. I hated the daily cold baths in the dorm’s grimy utility block, where we washed our shivering bodies side by side with flitting mosquito larvae and, occasionally, wall frogs. I resented the punishments, often meted out because of my classmates’ or dormmates’ shortcomings and not my own. I was too busy striving to be good. Every morning, as my fine-tooth comb fluffed up my cropped coils, now shaved so low you could sometimes see my scalp, I felt like an alien unto myself. I wondered if the other girls felt as alone and untethered from their mothers as I did without my hair. I wanted out of this place. I missed my family. And time moved so slowly, it was as if the whole school was trapped in amber.

I was in Class 2 (eighth grade) on the day in question, and one of the junior students, as we were called – the caste of girls without many privileges or freedoms or hair. There was cotton everywhere that day – decorating lawns, walkways, and tops of hedges. I’d left the dorms early and arrived in the classroom area to begin my chores for Green House, my school house. I was responsible for arranging Class 6B’s furniture into neat rows, cleaning the blackboard, and wiping the dust, bugs, and pencil shavings off the furniture and louvers. When I stepped onto the verandah on the second floor, I should have branched left into Class 6B. Instead, I swiveled right to look out across the campus shrouded in white. A tangle of emotions whispered to me over oceans and across borders like blown cotton. Nigeria, the Netherlands, and Nigeria again – Nigeria anew because I was learning my country all over again. It was a riddle as hard as a pebble that I carried everywhere, worrying its rigid, unyielding surface.

Maybe I would have asked someone why the manifestation of a demon condemned to serve his white conqueror was fashioned to look like a bad cartoon of a Black person with hair that looked like mine.

No one at Adesoye College was free. Not the boys who snuck into town at night to drink with locals and eventually had to sneak back to their narrow beds before lights-on. Not the girls who befriended the school matron, skipped the weevil-infested dining hall beans to gorge on jollof rice in her rose garden, and still had to bathe in the utility block the next morning.

This was what filled my thoughts on the verandah from where I could see the narrow lawn rectangles in front of the Class 1 block peering up at me. There was no cotton on that grass. Another student must have been cleaning down there that morning. I ran my fingers over the bright yellow metal railing that protruded from the brick chest-level wall. It was cold and lumpy.

Beauty wove into the anguish of boarding school like a golden thread along a hem – bobbing in and out, shining, then disappearing again. I loved how cool the mornings were in the dry season and the aroma of things burning in the distance – a farmer razing his field in preparation for the next planting; the incinerator beyond the girls’ dorm turning used sanitary pads and insect carcasses into ash; a dry bush whose tinders caught onto a fleeting spark and went up in flames. I loved the silence of early mornings in the classroom area, so starkly different from the chaos of the dorm. Intention was everywhere – someone had sat down and planned this place. Every building was built with hand-laid terracotta bricks, every flowering tree had been planted and tended to by careful hands. No lawn was ever overgrown. If a glass louver slipped from its frame and shattered, its shimmering replacement was never far.

Freedom. I gripped the railing and thought about the first time us juniors saw those senior boys rain down from the sky like colossal black hail. It was about a year before, when we were in Class 1, killing time between our evening class and dinner. The first boy shot down like a comet. It was so quick, he passed by the corners of our eyes like a speck. But the noise of his body landing was unmistakable. Thud! He landed on his feet and rolled forward in the grass from the momentum.

We ran to our ground-floor verandah, horrified. Before we could make out exactly what had happened, another one dropped down before us. The boys upstairs stood high above us, the next one to jump had one foot on the shallow brick wall and the other on the yellow railing as he held onto the vertical part of the railing for balance. We gazed at them, angels in white, blue, and maroon uniforms, chests heaving, eyes darting around the ground below. Did they know they could die if they didn’t aim correctly? Or at least break their teenage bones on the concrete. They had to be precise. If they pushed off too forcefully and flew too far, they would crumple against the hard pavement. If they didn’t push enough, another strip of pavement flanking the patch of lawn waited for them. We looked up from below, the way my brothers and I used to watch for egrets high above us. We all held our breath. My eyes grew as big as plates.

I suspected that maybe these boys who’d taken to leaping from the verandah had brushed against something like freedom in those milliseconds between catapulting themselves from the bright yellow railing one story up, and crashing down onto the grass. They had tasted that liminal sweetness when you became nothing but a being of its own definition – a flying body that launches itself into the air, not shoved out of its nest by impatient beaks or given names they hadn't chosen for themselves. Who could control them in the air? Who could tell them they weren’t magnificent? Who could tell them they weren’t beautiful or good or wanted?

I marveled as they launched themselves from the railing one by one. They were soaring albatrosses, broad and weightless in the air. They didn’t plummet like rocks – their uniform shirts and trousers caught the wind and ballooned and rippled around them. Some spread their arms wide like wings, others switched their legs in flight, some shouted into the air, others were silent as their bodies thudded to the ground and the grass received them. Each of them submitted himself to hope’s buoyancy, to gravity’s pull. They were resplendent in the red sunset – a procession of synchronized sky swimmers, leaping into invisible portals in the air, being reborn against the ground.

Freedom. I hoisted myself onto the half-wall and swallowed back the shock from the elevation. We were all doing restless, dangerous things in ACO. Was my teetering high above the ground so different from the boys and girls who climbed up the huge overhead water tank in the middle of the night to sign their names on the concrete in permanent marker? Or the boy who had thrown himself from the moving car that was carrying him to the sickbay when he had malaria because... well, we never got an explanation for why he did that, but after our initial nervous laughter dissipated, his urge to do it quietly resonated with me. Maybe we did these things to push back against the torment and insurmountable ache of homesickness the only ways we could. As I raised one foot onto the railing, I gripped the column for stability like I’d seen the senior boys do. I now knew why they did it. Even with just one foot on the railing, it felt precarious, and my gripless plastic soles could easily slip. My eyes slid shut and the cool air ached my nostrils.

Every week, as she freed, washed, and re-bound my hair in thin black threads in the private quiet of her bathroom, she salved my wounds, my confusion, and restless agitation, and tethered us both to Home.

I thought about picking the rubbery weevils out of my slop of beans in the dining hall. I thought about those brilliant egrets. I thought about the scent of jojoba shampoo on Saturday mornings.

I was ready to raise my other foot. Whatever happened, I thought, wherever I went on the other side of my flight, I would relish those fleeting seconds of nothing holding me, nothing trapping or surveilling me. I would escape, I would fly.

I sucked in a wave of air and stood there for what felt like a long time – one foot on the railing, the fog standing still around me, holding its breath.

***

Death is never far. Neither is rebirth. Some of us who left home early and had to morph as we migrated have died many small deaths, beginning from when we were as soft as down feathers, still sucking our thumbs. For years, we’ve been departing and reuniting with ourselves.

So, what did it mean that I – already familiar with ephemera, how easily things can disappear from us, and how malleable we become in the process – couldn’t partake in this spectacle of impermanence? What did it mean that I only stood there on the half-wall and smelled the fog; that I only looked out forlorn at the cotton; or that I carefully climbed down and entered the classroom to begin untangling the chairs from the tables?

My spirit and my body recalibrated in the quiet of the classroom. My pulse pounding in my ears dissipated. I heard the wood scraping across the concrete floors. My body settled. I noticed and felt the weight and movement of small invisible things like the tender caress of the cross breeze when I opened the classroom louvers. Peace.

When I would stumble into pockets of stillness like this during my six years in ACO, beauty would parse itself from ugliness. Small delights — as small as biting into puff-puff pastries hot from the campus kitchen that tasted just like Dutch olie bollen –– transported me far beyond the school walls, to the bathtub where my mom rinsed my pain away, to nestling in the soft safety between her knees as she threaded my hair. I clung to these things, the precious sweetness of them, the ways they expanded the walls of my heart. When it was finally my turn to graduate, my heart was heavy. By then, all I could see in ACO was its beauty.

I saw my parents agitate back at the world when things were in flux and unjust. I also watched them simultaneously create sacred quietude. Maybe they knew that when you sit in stillness, it’s easier to feel everything coming and going around you, everything dying and being born, what is true, and where you belong in that cosmic waltz. And maybe that is as transcendent as leaving, as leaping, as flying.

This is one of the most beautiful essays I have ever read. Thank you.

Utterly magnificent writing. I won't forget this piece. Thank you, Adaeze.