The Roads She's Traveled

"What paths do women’s stories take along those arduous journeys toward becoming themselves?" An excerpt of "I Could Name God in Twelve Ways."

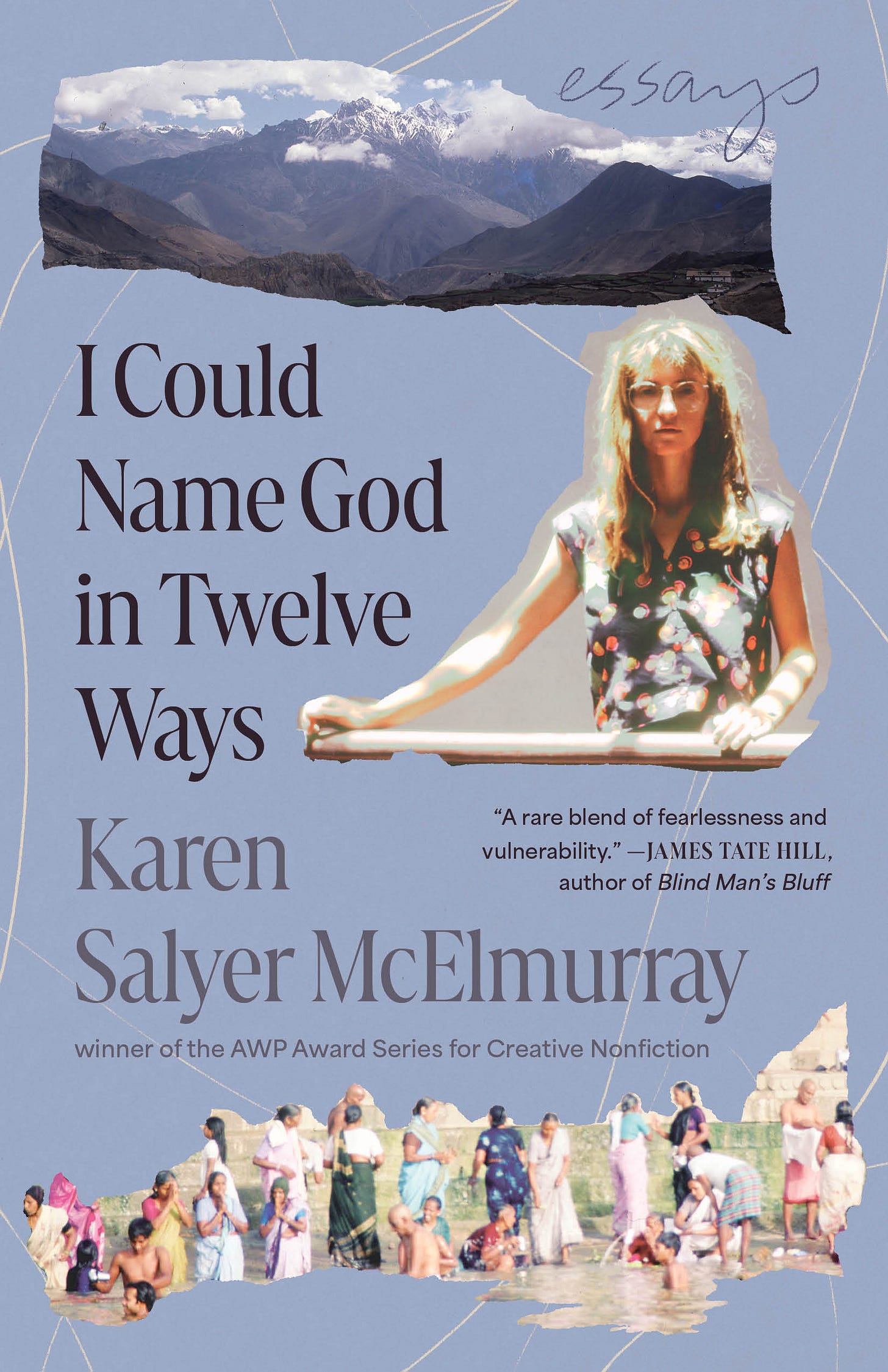

This essay is excerpted from I Could Name God in Twelve Ways published by the University Press of Kentucky. Award-winning writer Karen Salyer McElmurray details her life's journey across continents and decades in this poetic collection that is equal parts essay-as-memoir, memoir-as-Künstlerroman, and travelogue-as-meditation. It is about the deserts of India. A hospital ward in Maryland. The blue seas of Greece. A greenhouse in Virginia. It is about the spirit houses of Thailand. The mountains of eastern Kentucky. The depths of the Grand Canyon. A creative writing classroom in Georgia. An attic in a generations-old house. It is about coming to terms with both memory and the power of writing itself. ©Karen Salyer McElmurray.

—

When I wanted to be alone, I took my notebook along the dirt path, made my way past what used to be a hogpen, and climbed the hill behind Fannie Ellen’s house. I was twenty years old, and I needed solitude, though I wouldn’t understand why for years. All I knew was that my childhood had nearly eaten me alive. At sixteen, I’d given up my son for adoption, and since then I’d partied hard, filling up my emptiness with grief and confusion. Now I was trying a different life on for size: moving to eastern Kentucky to live with my granny in Johnson County while I attended Prestonsburg Community College. As I climbed the hill through a sting of briars, I named trees. Sycamore. Chestnut. Tree of heaven. The sound of the wind in those trees was holy.

At the top of the hill was a rock cliff, where I sat looking out over the whole wide world. Across from Fannie Ellen’s lived distant cousins. Sue, married to Clifford, a laid-off miner. Faye and Alvin, who owned the country store. In my notebook I drew maps of that world. Jenny’s Creek. Bull Creek. Puncheon. Water Gap. Abbott Mountain. Highway 1428 cut its way through the valley toward Floyd County, where my mother and all my maternal relatives lived. Another granny. My pa. The aunts and uncles and cousins—all of them fine for a visit, but none of them offered me a home. Home was far away, deep down and unseen. I got close to it by living with Fannie Ellen and by visiting Bear Holler, the abandoned farm where she’d been raised.

I had an idea of the woman I wanted to become, but most days I was a misfit. I was a stone rattling around in an empty Mason jar. As the sun slipped over the valley, I held my notebook close and studied a world I wanted badly to understand.

Fannie Ellen and I had walked that land more than once. She taught me how to know greens. Poor Man’s Bacon. Creasy. Dock. She taught me about wishes, since Bear Holler had been the place of her girlhood dreams. She’d wanted to be a nurse, an ambition she gave up when she chose to marry my granddaddy. Home became roof and porch, became good men and good women, a fine line of distinction between them. Good men looked after their households, she said, and their women rose up at daylight and prepared their families in the ways of the Lord. I had no idea what good meant, but I’d tried for as long as I could remember to figure it out. My beliefs were books—everything from girl mysteries to Russian novels and the histories of martyred saints. As far as I could tell, God was made of thunderstorms, art, and the stories I knew about the women I came from. Strong women. Granny women. Even a bearded woman who ran off to join a traveling carnival. Armentia George. Exer. Nethaladia. Ida Mae. I kept their names in my notebook.

I wasn’t a woman yet, and I sure wasn’t good. I slipped out at midnight and drove over to Prestonsburg and Dewey Lake to swim with the boys I’d met at Dairy Cheer. I went dancing up at Pikeville, at Marlow Country Palace. I took rides in a coal rig with a boy named Little Boots, who taught me how to shift gears. I was always ready for a fight, as ready to head off into some big city as I was to stay put in Hagerhill. I had an idea of the woman I wanted to become, but most days I was a misfit. I was a stone rattling around in an empty Mason jar. As the sun slipped over the valley, I held my notebook close and studied a world I wanted badly to understand.

* * *

I left Hagerhill and went on to this college and that. I earned one degree, another. I gave myself away to an artist named Tom, then lived for a few years with a woman named Margaret, who tried to help me find my way back. I put love behind a wall I couldn’t climb and told myself I felt nothing at all. I filled notebook after notebook with words and sentences and remembered dreams. I dreamed about crossing the creosote bridge in front of Fannie Ellen’s house. I dreamed of the stone foundations of my great-grandparents’ house up Bear Holler. I wrote stories and poems. I threw my hat in the ring for jobs and conferences and publications. And I always went back, sleeping or awake, to the land of my ancestors. I was forty years old, and I drove the long miles like they were hunger. I craved eastern Kentucky like it was the one good meal that could finally satisfy me.

As far as I could tell, God was made of thunderstorms, art, and the stories I knew about the women I came from. Strong women. Granny women. Even a bearded woman who ran off to join a traveling carnival. Armentia George. Exer. Nethaladia. Ida Mae. I kept their names in my notebook.

In Floyd County, my mother was in the final stages of Alzheimer’s. Granny and Pa, the aunts and uncles, they were gone too. There were still cousins, but I hardly knew them, and the Pentecostal Holiness Church across Highway 114 near my mother’s house had become a car sales lot. In Hagerhill, Fannie Ellen was in nursing care, where she would pass at ninety-two. It was hard to see where any of it used to be, with her house and the hill I’d climbed all lying beneath new Route 23. I stayed as many days as I could on trips back, trying to hold that world on my tongue like it was Communion. It was an odd holiness. When I tried to walk up Bear Holler a blonde-headed woman came out of a house at the mouth of the hollow. Her eyes narrowed. A shirtless man in cowboy boots picked up a fist-sized rock and aimed it at me. At my mother’s nursing home, a blind one-hundred-year-old woman looked out over the empty dining room tables. “Lord, honey,” she said. “Look what they done to them mountaintops.”

* * *

During those years, I gathered memories I could tell about the world I’d left behind. A short story was about a girl named Mary Ruth who worked at Murphy’s Five and Dime. She loved working at night, winding up all the musical jewelry boxes and dreaming of other towns. I wrote about a collector of dolls, about a lover of snakes and Jesus, about a man who painted the walls of his house with images from the book of Revelation. The women I wrote drifted through the world as much as I had. Leah, a runaway, panhandled on a St. Louis street corner when she felt her baby’s heartbeat for the first time. These stories of a floating world grew bigger. Leah became a memoir. My first novel was about a woman named Ruth Blue, who believed more in visions of angels than she did her own son’s life. In another novel, Miracelle Loving traveled from Fairbanks to Miami, telling false fortunes. The women I wrote were uncertain of their lovers, their homes, their next meals. They rode miles toward futures they couldn’t see, hitched rides along strange highways. Their journeys seemed to have no beginning, no middle, no end, and I let them wander, seeking exactly who they might someday become.

* * *

The women who have inhabited my prose—Leah, Sarah, Ruby, Ruth, Pearl, Lory, Miracelle—have kept a toehold on belonging in the world. Their stories have been about grief and rage. About loss and hurt. About seemingly insurmountable damage. If there’s a common denominator for these women, one word—journey—covers it best. The women on my pages have traveled the stumbles of dirt paths, the perimeters of rooms in houses they seldom leave. They have inhabited spaces they struggle to escape, be they the heads of hollows or the confines of their own hearts. Some readers find the women I have written helpless. “Why,” they want to know, “don’t they just get on with it?” Once I wrote a character who spent a long night grieving the lover who had just slapped her across the face and kicked her out of a bar. As she walked across the parking lot, she tripped and fell and sat staring at a fistful of dirt. “What,” a workshop peer wanted to know, “is all this silly business about dirt?”

The women I wrote drifted through the world as much as I had…The women I wrote were uncertain of their lovers, their homes, their next meals. They rode miles toward futures they couldn’t see, hitched rides along strange highways. Their journeys seemed to have no beginning, no middle, no end, and I let them wander, seeking exactly who they might someday become.

I find the women I have written more held fast than helpless. They are fierce fighters, whether the fight is inside themselves or out. They have been beset by distances. They long for roads that will take them nowhere as much as they long for ones that might take them back home. They try mightily to find the selves they’ve lost or never had in the first place.

* * *

A few summers ago when I visited Kentucky, I rented a room at Jenny Wiley State Park. I rode around town, had a meal at Billy Ray’s Restaurant and then took 114, the old road beside what used to be my mother’s house. A planter sat on the porch next to the metal chair my pa used to sit in, whittling cedar. A car in the driveway belonged to this cousin or that one, not a one I really knew. I was lonely, but I needed silence. Come afternoon, I hiked in the park and climbed a hill to the unmarked grave of a soldier’s wife. Beyond me was a blur of ridge and lake and, beyond that, an empty expanse of rutted hills. It began to rain, so back at the lodge, I sipped wine at the karaoke bar and sang along to easy-listening country until that left me wanting my room and a bed and bad television movies. In my burrow of sheets and blankets, the cold from the open balcony doors touched my face. Just sleep now, a voice said. Sleep and see what you can see. Like that, the stories I hadn’t found all day found me.

“Your stories are like dreams,” a friend once said of my writing, and so it was. Mist became a ghost shape, a ghost became a body, and Fannie Ellen stood beside my bed. Her veiny hands reached for mine. “Follow me,” she said, and I did. We stepped through the balcony doors onto the red tile of her kitchen floor, and we stood by the window, looking up at the hill I used to climb. We climbed until the top of that hill became a road, and we took that too. We rode along all the old roads I’d once taken. 1428. 114. 23. We passed the mouths of hollows, the lit windows of houses, doors that opened to let us in. We rode until highways became interstates, until interstates were nothing but mountains. In the distance, some of those mountains had been laid bare, stripped to their bones, made of nothing but grief. But Fannie Ellen still said the old words, the holy ones.

* * *

Once a friend wrote to me after reading a draft of my novel Wanting Radiance. He worried that readers would wonder why late-thirties Miracelle Loving, the main character, hadn’t married and settled down yet. He seemed to want a stronger plot, maybe a plan for my character’s life. I sat down, trying hard to sketch a plan for Miracelle, but all I came up with were questions. Why choose riding the roads over a home? Is it because of how highways sound at night? Can strangers fill up your heart more than safety and love? Those were all questions I asked myself until I was forty-five and chose to share my life with a partner. Questions. Dreams. Journeys. Those are the ways stories have revealed themselves to me. Narrative arc. Structure. Plot. Are women’s lives always that clear? Mine certainly hasn’t been. The journeys have always been challenging, both on the page and along the roads I’ve traveled.

I still wait for the eastern Kentucky earth to tell me something. I grieve for land that no longer exists, for mountains razed by highways, highways slashing through the memory of wilderness. I grieve for memories and the people long gone. I am gone, too, in a lot of ways. I have chosen a different path than Fannie Ellen wanted for me.

If I asked Miracelle Loving or any of those women I have imagined whether their journeys have been straightforward, I think they’d say no. Miracelle might describe some night ride on a highway she took on a whim—a whim that led to a two-lane, then to an unmarked gravel road and some juke joint with a broken neon sign, a great place to get just one drink before heading on her way. Who knows what could happen next? That’s Miracelle’s story, and it was my own, for years and years. Sometimes, I’ve come to think, my stories have meant that an ending might well come before the middle, followed by another surprising turn in the road. The opening might end up being on the last page, just as the lights to the last bar come on. Beginning. Middle. End. What paths do women’s stories take along those arduous journeys toward becoming themselves?

* * *

I still wait for the eastern Kentucky earth to tell me something. I grieve for land that no longer exists, for mountains razed by highways, highways slashing through the memory of wilderness. I grieve for memories and the people long gone. I am gone, too, in a lot of ways. I have chosen a different path than Fannie Ellen wanted for me. I rise up with good daylight, but it’s to write the stories of what was and the stories of what might be. I’m a seeker. I drive home to Kentucky again and again, trying to summon the ghosts of all the places that once were. Like Miracelle Loving says as she contemplates the places her journey toward peace has taken her, “I didn’t know of what I was more afraid—roads out, or all the roads leading inside.” I don’t much know either, but I take the next turn, and the one after that.

What a stunning piece of writing. I didn't mean to read it, but couldn't stop! How it evokes an inner and outer geography, how Kentucky is so tied to moving and yet staying grounded, finding that ground. Oh. I will read more!!!!

Beautiful, evocative - my morning coffee was supposed to be accompanied by reading the news, but instead I tripped over this and now my day is wrapped in something far more thought provoking and rich. And I want to read more of your writing … thank you for this unexpected gift.