The Sound of Grief

Hearing her father's voice on a home video prompted Vishakha to confront her father's alcohol-related death, and the bitter resentment she harbored toward him for her family’s financial ruin.

My ears were close to the laptop speakers, which were at full volume. My younger brother Vikrant was sitting beside me, his eyes fixed on the computer screen. We were watching a home video of our parents sitting in a pooja for their newly born son, Adi, our youngest sibling. My father was wearing a classic white kurta-pajama and my mother was in a red saree, a matching vermilion mark in the parting of her hair. They were sitting cross-legged in front of a havan, which is a fire ritual performed on special occasions. Their hands were positioned near their chests in namaste, while they listened to the pandit (a Hindu priest) humming chants. With my parents’ approval, the pandit slipped in a few Sanskrit words. “Om Tryambakam Yajamahe Sugandhim Pushtibardhanam Urvarukamiva Bandhanan Mrityormukshiyya Ma Mrityat….” Back then, I thought the chanting words sounded like gibberish, some fancy Hindi words that only adults use. These words that once held no meaning for me were now suddenly bringing up clear memories of my father. Ironically, this chant is the most potent one used in Hindu households to ward off evil, fend off disaster, and avert premature death. However, the Sanskrit chants did not work. Neither did they fend off disaster nor my father’s death.

In the video, I spotted my 7-year-old self running around with Vikrant in the background. I was wearing an orange salwar suit and my hair was in pigtails. I heard my father’s coarse voice and thought how strangely soothing it sounded, but a few seconds later, a looming sensation struck me. While I recognized the voice on the video and the gravitas it held, I can’t say that if that voice were to call me now, I might recognize it. I was disappointed. In just ten years, I’d forgotten what my father sounded like.

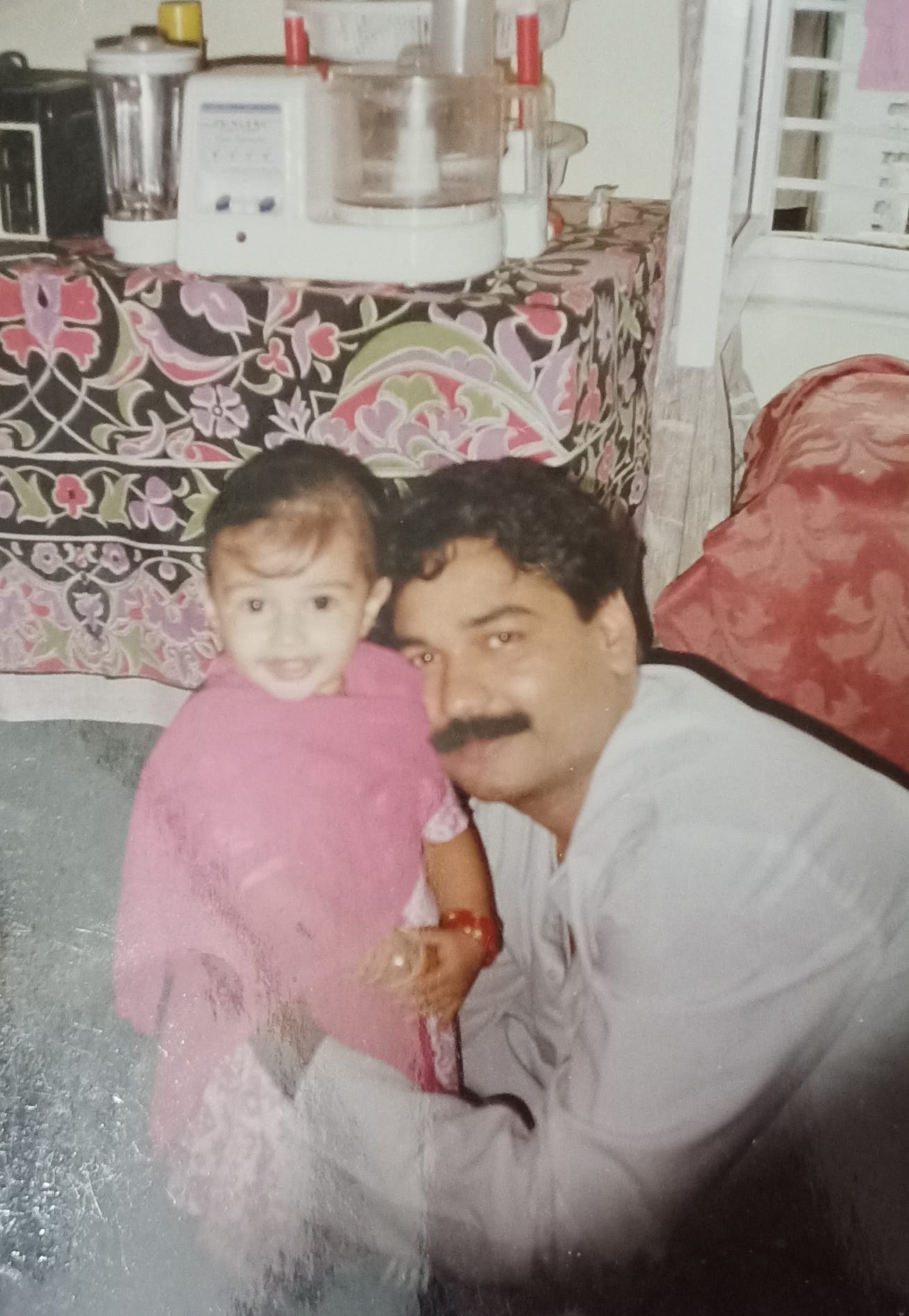

That night, after watching the video, I scrolled through old photos on my phone. The pictures that I found made me realize that over the years, though I’ve seen my mother age, (lines creeping near her mouth, freckles slowly covering her cheeks) I couldn’t imagine my father getting older. What would he look like with grey hair or a turkey neck? Would crow's feet form near his hooded eyes, or had he lived, would he have a furrowed forehead? Maybe his belly would have grown or his thick mustache gone white. At that moment, I wanted to know that man, to feel close to him. But this desire was new. For many years, I had intentionally kept memories of my father at bay. I was only 15 when he suddenly died of liver failure. Back then, my family was grieving and in pain, but moreover, we were also suffering from the financial hole my father’s death had put us in. The latter became our top priority.

I heard my father’s coarse voice and thought how strangely soothing it sounded, but a few seconds later, a looming sensation struck me. While I recognized the voice on the video and the gravitas it held, I can’t say that if that voice were to call me now, I might recognize it…In just ten years, I’d forgotten what my father sounded like.

My mother sobbed every day, especially when it became crystal clear to her that my father had left us with absolutely nothing but crippling debt. As the months passed, the crying went down to twice a week, then once a week, and finally only on important occasions, like festivals or his death anniversary.

Eleven years have gone by, and now both my brothers live in different cities, and I am the only one that stays with my mother in Kanpur, a small town in India. Recently, I heard her start to privately sob again. That night, she sat next to me while I read a book, and suddenly said, “When your father was gone, I was so busy building your lives that I did not have the time to properly honor him, but now I feel the loneliness. I have no one that I can take care of.” Joan Didion was right when she wrote, “Grief, when it comes, is nothing we expect it to be.”

As for me, now and then, small moments will remind me of his absence. I once saw my best friend’s father hug her tightly and was jolted back to an occasion when my father returned home late at night from a business trip, laden with gifts. My father tiptoed into our bedroom while my siblings were fast asleep. He caressed my face and I instantly sat up and hugged him tightly. His arms felt like a big cloud and he smelled like a mix of aftershave and cigarettes. I rocked my brother Vikrant awake. To our surprise, my father handed him a massive toy car, and me an mp4 player, something I had longed for. Adi, my youngest brother was given a colorful bicycle. Before falling back to sleep, I overheard my mother questioning him about the amount of money he’d spent. He shushed her and said not to worry.

Whenever I miss my father, I also miss my younger self, the girl in the video with the pigtails, the one who had the freedom to explore, and was unfamiliar with the responsibilities of adulthood. People say that grief is the response to the loss of a loved one but I think it is also the response to the loss of the past self.

My father was a civil contractor, and my mother was a housewife. After he died, his business died as well. At the time of his death, my mother had 7,000 rupees in her bank account, which is about $85 in U.S. dollars. The only thing she knew was that we were in debt. The woman who had a drawer full of designer shoes and handbags quickly realized that she had to earn for herself and her children.

Both of my parents grew up poor, so the status they had reached by adulthood meant a lot to them, especially to my mother. She wanted to preserve my father’s image. Thus, she lied to everyone about our financial condition and the true nature of our father’s death.

My mother sobbed every day, especially when it became crystal clear to her that my father had left us with absolutely nothing but crippling debt…Eleven years have gone by, and now both my brothers live in different cities, and I am the only one that stays with my mother in Kanpur, a small town in India. Recently, I heard her start to privately sob again.

One day I saw red stains in the family bathroom. It didn’t register to me at first that the stains on the floor were blood. I went straight to my parents’ room only to find my mother counting bundles of money. She looked up at me with red eyes. Before she could speak, I knew something terrible had happened.

“Your father is hospitalized. He vomited blood last night,” she said and quickly went back to counting the rupees.

I could not fathom my father dead. For me he was untouchable. I was scared to see him in such a vulnerable state, so I never visited him in the ICU. Days later, though, when he was moved to his hospital room, I gathered the courage to see him. It was his 40th birthday. My brothers and I brought my father his favorite cake—pineapplslathered with frosting with a cherry on top. My father lay on his bed. An IV drip hung near him. The blackness under his eyes was prominent; his arms were like two twigs. The stubble on his face looked odd and made him look impoverished. The only traits I could recognize were his mustache and massive belly, which looked bigger because of the inflammation caused by liver cirrhosis. His lips curved, forming a weak smile when he saw us enter. I wanted to cry at that moment, but I didn’t. We had no idea that he would die a year later.

When my father came back from the hospital, I served him spinach soup every evening. One night, while heating the soup I asked my mother, “Why does he need to drink this soup?”

“Because it helps with the iron in the blood,” she said.

I swirled the bubbling soup for a second. “How bad is it?” I asked.

“Very bad.”

My father was an alcoholic. I am not sure why I never picked up on this detail. Maybe because I don’t remember him behaving differently when he drank. He was the same to me, day or night.

My father stayed home and sober for six months straight. The longest he had ever been away from his work travels. After one of his hospital check-ups, my mom came back home with sweets, and a grin plastered on her face. The recent hospital report yielded great news. The scar tissue on his liver was almost gone. Not unlike my parent’s entire savings that went into paying for my father’s hospital bills and medication. My father immediately started making calls to get work locally. However, the news of his health condition had spread throughout our town. He had no choice but to go back to traveling. “I’m the man of the house, I need to earn,” he said. My mother pleaded with him. “You need to stay alive,” she said. But he did not listen and started traveling the very next day. Soon after, he started drinking again.

Three months after my father’s death, my mother started a clothing boutique from our home. She put up a poster at the gate of our building and distributed marketing cards to friends and neighbors. After getting her first customer, she worked diligently, but the customer was unhappy. I was with my brothers in the living room watching a Hindi movie on television when I overheard the customer complain, “No, no this doesn’t look nice…” Gradually, the customer's voice got louder, so much so, we could barely hear the TV. The woman began screaming, telling my mother that she had failed and had done a bad job. Listening to the insults I realized that first-hand humiliation is far better than witnessing the humiliation of a loved one. That night, my mother sobbed uncontrollably while my brothers tried to console her. The more humiliation we faced, the more repulsed I became by my father’s memory. He was the reason we were in this financial mess after all. His death led to my family’s financial collapse, which led to our humiliation.

To pay off the home loan and to afford our school fees, my mother sold all her jewelry. Since I was the eldest, I accompanied her to the pawn shop. Gold rings encrusted with diamonds of various sizes, beautiful necklaces she had saved for my wedding day, the designer golden watch that my father once gifted her, everything was sold. Everything except her mangal sutra, a necklace decorated with black and gold beads and a gold pendant attached to it. The mangal sutra is given to the bride as a symbol of her marriage. One day when I was 17, my school teacher questioned me in front of the entire class about my unpaid tuition. I felt humiliated, all over again. When I got home, I handed my mother a note from my teacher. She read it and slowly walked across the room and opened her closet. She stared inside for a few moments. That evening, my mother and I returned to the pawn shop and she sold her mangal sutra. “What is the use of this?” she said casually, “I can’t wear it anyways.”

Whenever I miss my father, I also miss my younger self, the girl in the video with the pigtails, the one who had the freedom to explore, and was unfamiliar with the responsibilities of adulthood. People say that grief is the response to the loss of a loved one but I think it is also the response to the loss of the past self.

My mother finally accepted we were poor. Soon after, she stopped eating regularly. She stopped wearing embroidered suits and started wearing cheap cotton ones that hung oddly on her now thin body frame. The blonde streaks in her hair began to vanish as new silver strands took their place. To go places, we had to travel through the cheapest mode of transportation like rickshaws and three-wheeler green tempos, cramped with strangers. We walked on asphalt roads with flimsy footwear, and many nights survived on instant ramen noodles. When I was a child, I used to look at the tanned poor people on the road in their cheap, tattered clothes, while I sat inside a spacious sedan with full-blown air conditioning, and think, How can they live so deprived like that? Now, I was one of them.

A few years ago, I started having arguments in my head. One part of my brain was on my father’s side, and the other part was with the angry 15-year-old daughter who lost her father.

My father knew that his liver was failing. And yet, he chose to drink. Sometimes I wonder if he felt so lost that he stopped caring about his wife and three children. Did he ever think about how his wife or his kids would tackle the financial burden?

This argument carried on inside for years. I wanted to understand his perspective but somehow I couldn’t. Every time my mother faced the humiliation of not being able to pay some bill, I blamed him. When my 14-year-old brother returned home crying after falling in a ditch on a rainy evening, I blamed him. When I cut myself several times, trying to cope with anger, confusion, and grief, I blamed him. Maybe if it had been a more “natural” death, I told myself, then I could have blamed my kismet. But that wasn’t the case, his choice to keep working and drinking led to his demise, and then later, ours. Yet, as hard as I tried to keep my feelings at bay by forgetting his voice and his image, I finally came to realize that underneath my anger, I missed him.

A couple of days after watching the home video, I went through some family old photos. To my surprise, my vision became blurry and at once, a stream of tears flowed, like water over the dam. The gate that once held back my anger, as well as my love, had been lifted.