To Be Well

An unmothered woman’s search for real love. The first in a series called "Writing the Mother Wound."

This is the first in a series called Writing the Mother Wound, edited by and Danielle Amir Jackson, and originally published in Longreads.

Introduction…

I’ve been writing about my relationship with my mother for a long time, but these stories were hidden in journals and computer files. Then my brother, my Superman and first best friend, died in 2013, and I went reeling into the darkest time of my life. I quickly learned that this grief was dangerous, it could take me out and for a time I was letting it. I still remember distinctly the moment I decided to live: I went into my 8-year-old daughter’s room check on her, which I’ve done every night since she was born and still do now when she’s home from college. I pulled the overs up under her chin, kissed her forehead and looked at her. I knew I couldn’t leave her the way I’d been left. I had to climb out of that abyss but I didn’t know how, so I did what I’ve always done—I turned to literature.

I started searching out writing about grief—essays, poems, memoirs, novels. I was looking for respite and escape, I needed to know that I wasn’t alone & I needed evidence that I could survive. Then I read ’s essay “Heroin/e” and stopped when I read this line: “It is perhaps the greatest misperception of the death of a loved one: that it will end there, that death itself will be the largest blow. No one told me that in the wake of that grief other grief’s would ensue.”

By this time my mother and I weren’t speaking. We’d had a difficult relationship for much of my life but it got much worse after Carlos died. My mother’s grief was rageful, and I couldn’t handle it and my own grief, so we stopped talking as we had so many times over the years. She didn’t call me and I didn’t call her. Once I ran into her at my aunt’s house. When she saw me, her face curled in disgust, she stood up in a huff and said: “Me voy.” As she walked by me, she pulled in her shoulder so she wouldn’t touch me.

There was no running from the torment this relationship had caused me. Mother is a foundation from which we build our own, so what happens when you don’t have one? I was starting to see how that relationship influenced every relationship I had, platonic and romantic.

So what did I do? I threw myself into researching mother daughter relationships. That’s where I found the term “mother wound,” and that’s where the seeds of “Writing the Mother Wound” were planted. It’s become my life’s work.

I’ve been doing this work ever since, building curricula and teaching dozens of multi-week and one day classes online and throughout the country. It was a standing room only panel at the 2019 edition of AWP on writing the mother wound that led to my partnership with Longreads where this essay, “To Be Well: An Unmothered Woman’s Search for Love,” an excerpt of the memoir-in-progress, was published.

I’ve kept working on the memoir and I kept publishing excerpts, despite knowing for some time that something was missing. Then ma died last June, leaving me all her writing, including an unfinished memoir and dozens of journals. In the writing she shared that she was leaving her stories to me “para que Vanessa escriba un libro.”

I spent months reading everything, taking my time because of the visceral reaction in my body—I shook, my heart thrashed, jaw tensed, and I cried out of sadness and grief and rage and what-the-fuck, ma? In the writings she answered so many questions, filled in so many blank spots. And she gave me a more nuanced, complicated story.

I’d found what I was missing—ma’s stories of her life in her hand.

I’m still working on weaving her stories with mine, including this essay which has morphed into a longer one that I’m not quite ready to share. Suffice it to say that what my mother felt was more than shame over my falling in love and marrying a butch woman. She was scared for me because of what she lived with her butch partner Millie for thirty years.

That story I’ll tell in this new memoir I’m working on, which we are in many ways writing together, me and my ma. This time, I have her blessing.

Essay…

To Be Well: An Unmothered Woman’s Search for Real Love

by

In one of my earliest memories, my mother is leaning on the washing machine in our kitchen smoking a cigarette. She is watching her butch partner, Millie, who is on the other side of the room. Their eyes are locked. My mother smirks and takes a long drag of her cigarette. Millie walks toward her, leans her weight on my mother’s body, and kisses her. The smoke seeps out of their open mouths. I giggle and look away, blushing.

We never talked about who Millie was to Mom or to her children. As a kid, I made Millie Father’s Day cards, complete with cardboard collar and tie. At some point, we started referring to Millie as our aunt when people asked who she was or how we were related. I was too young to understand what this meant.

I met my now wife Katia in August 2015 at a women’s music festival in Michigan. We fell in love quickly, and when my mother heard whisperings of my relationship, she sent me cruel text messages, criticizing me for being a bad daughter and mother.

We never talked about who Millie was to Mom or to her children. As a kid, I made Millie Father’s Day cards, complete with cardboard collar and tie. At some point, we started referring to Millie as our aunt when people asked who she was or how we were related. I was too young to understand what this meant.

She didn’t ask me who Katia was or if she was good to me. “Les di un mal ejemplo,” she said.

I deleted her messages without responding and blocked her when they got to be too much.

I married Katia on May 10th of 2019. My mother was not there. I didn’t invite her, but she wouldn’t have come even if I had.

My relationship with Katia is the first where I am not clawing for the love of an emotionally unavailable person, like I’ve done so many times in the past, repeating the “love me, please love me” cycle I learned from my relationship with my mother. This doesn’t matter to my mother. It doesn’t matter that Katia shows up for me, is supportive, kind, and reliable. It doesn’t matter that Katia loves my daughter, so much so that she included her in her wedding vows, turning to her and promising to love her and be there for her like her own.

All that matters to my mother is that Katia is a woman.

***

My mother and I have never been close. She was abusive and harsh when I was growing up, and I learned early on that no one could protect me from her. Not even Millie, though she tried. I left to attend boarding school at 13 and never returned.

Boarding school was my way out. At 13 I had to leave to save my own life.

She’s been in and out of my life since. Whenever I disobey her or don’t live my life the way she thinks I should, which is often, she punishes me by denying me her love.

She’s done this so many times, leaving me longing for her love. A friend asked me recently, “How many times have you lost your mother?” The question connotes that I had her love at some point. It pains me to say it, and I feel so much guilt writing this, but the truth is I’ve never felt like I had my mother’s consistent love. Not as a child. Not as an adult. But nothing exists in a vacuum. I know my mother is unable to mother me because of her own trauma.

***

My mother was raised in Honduras in the kind of poverty we only see in Save the Children commercials. She once told me a story of when she was 11 years old. She’s sitting on the latrine. It looks like the one I used on my first trip to Honduras when I was 9. I was a spoiled Americana who had only used a toilet that flushed so I didn’t have to look at where the stuff went. The toilets at home were white and eddied the business away. This thing was a black, bottomless hole where I imagined all sorts of vermin squirmed, waiting for an unsuspecting child like me for them to grab and chew on.

The wooden planks of the shack were old and splintered, black in parts where the moisture had seeped into the grain, which was now growing mold. You could peek out in spots where the wood had warped. Mom is sitting on the wooden top, no toilet seat to protect her rear, but by this time she knew how to sit so the splinters didn’t dig into her. She’s grown immune to the stench and the frightening thoughts of what’s festering in that hole. She’s swinging her skinny legs, elbows propped on her knees, face in her hands. She’s scarred from mosquito bites and so many falls. She picks at a scab and wonders what they’ll eat that night. Tortillas y frijoles, for sure. The staple diet de los pobres. She hopes her abuelita Tinita has scrounged enough to buy at least a piece of meat. Un pollito o una carnesita de res dripping in fat and juices. It’s been so long since Mom ate meat.

That’s when she feels the shudder in her stomach, like something is moving, slithering. Then she starts to choke. Something has lodged in her throat so she can’t breathe in or out. She kicks the flimsy wooden door of the latrine. Her worn-too-many-times panties and shorts are still around her ankles. Her T-shirt is still rolled up above her belly button. Abuelita, who is sitting on a stool in the patio shelling beans, runs to her and shoves her hand into Mom’s mouth. Mom gags but nothing comes up. Tinita shoves her fingers deeper until she feels it. She grabs hold and yanks, pulls out a tapeworm two feet long. Mom falls back onto the dirt, sweating and heaving.

I met my now wife Katia in August 2015 at a women’s music festival in Michigan. We fell in love quickly, and when my mother heard whisperings of my relationship, she sent me cruel text messages, criticizing me for being a bad daughter and mother. She didn’t ask me who Katia was or if she was good to me. “Les di un mal ejemplo,” she said. I deleted her messages without responding and blocked her when they got to be too much.

Mom told me stories of her childhood when she wanted me to see how good I had it. When she was calling me ungrateful. Stories about how she ran barefoot to school in the morning because shoes were a luxury so the one pair she had were saved for special occasions. If she was late, she would have no milk for the day. It was powdered and tasted like chalk, and bugs floated on the top of the yellow liquid. But they drank it because it was the only milk they had.

Then there was the story of her muñequita. The Catholic Church up the road gave Christmas gifts to the children in the barrio. They were donated by charities from overseas, but by the time the load reached the barrio, the rich had taken their pick from the lot. So one year, Mom was given just a doll’s head. She had a mass of brown curls and big blue eyes. It was the only doll Mom had.

A few days later, Mom woke to find that Abuelita had fashioned a body for the doll using rags she sewed together and stuffed with leaves and dirt. She made the doll a dress out of one Mom had outgrown. Mom slept with that doll for years. She cried every single time she told that story.

We were poor growing up, but for us poverty meant living in Bushwick, Brooklyn, a neighborhood that was a pile of rubble, in an apartment with walls that chipped and flaked in chunks, giving me asthma and my brother lead poisoning. Poverty for us meant not having the latest kicks and not being able to go on school trips that cost money.

Poverty for my mother meant hunger. It meant watching her baby sister have seizures and die because they didn’t have access to adequate health care. When my mother told me this story, she clawed her hands and flailed her arms to show me como le brincaba el cuerpo a la niña, who was not yet a year old.

A friend asked me recently, “How many times have you lost your mother?” The question connotes that I had her love at some point. It pains me to say it, and I feel so much guilt writing this, but the truth is I’ve never felt like I had my mother’s consistent love. Not as a child. Not as an adult.

Poverty for my mother meant hunger and being unmothered.

My grandmother started working at 5 years old. When she had her children, she worked as a maid for wealthy families who lived in gated mansions surrounded by the shacks of the poor. Three of Abuela’s children died as a result of poverty. Six months after one of her daughters died, the infant my mother saw convulse, she left Honduras for good. She moved to Puerto Rico with the Turkish family she was working for. My mother, who was then 9, was left with her grandmother Tinita. My mother has said: Tinita fue mi madre. She didn’t see her birth mother for five years.

Hunger taught Mom that life was brutal, but she didn’t imagine it could be worse in this country. Nothing could have prepared her.

***

My mother was 15 when she arrived to the U.S. She hadn’t been here two days before her mother’s husband started molesting her. She still had Honduran soil under her fingernails.

My brother was conceived in that rape. My grandmother blamed my mother. My mother has never gotten over what happened to her. I know that’s why she couldn’t and still can’t mother me.

I am unmothered because my mother was unmothered. ***

As a kid, when I watched Claire Huxtable and Elyse Keaton on TV and saw the mothers and their children in my neighborhood, I often wondered why my mother wasn’t like them. Yes, she fed and clothed me, and made sure I had a roof over my head, but she wasn’t tender or affectionate.

Once when I was 5 or 6, I went with her to El Faro, the supermarket on the corner. I reached up for her hand to cross the street and she swatted me away. “Porque siempre tienes que estar encima de mi?” That memory still makes me wince.

***

Months into my relationship with Katia, my aunt had a dinner for the family. I decided not to attend because I knew my mother would be there, but my daughter begged to go.

I saw my mother standing in front of the building as soon as we turned the corner. I told Katia to park behind a large van so my mother couldn’t see us. Moments after my daughter got out of the car, I heard my mother.

“Where’s your mother? Tell her to come. Tell her to come.” The bass in her voice increased with each “Tell her to come.” I couldn’t see her face, but I know that roar. As a kid it would send me running up into the plum tree in our backyard.

I told Katia to hit the gas. I watched my mother yell and flail her arms in the rear view mirror. I later found out she cornered my daughter to interrogate her.

This is how Katia met my mother. She drove us to a nearby park where I sobbed into her chest.

***

I spent much of my life trying to win my mother’s love. I know now that she did the best she could with what she had, but the little girl I was didn’t get what she needed, and the young woman I was still suffered for that love well into adulthood.

I repeated the “love me, please love me” cycle for a long time after leaving my mother’s house. I broke my heart countless times as a result, falling for people who were emotionally unavailable like my mother. I even repeated the cycle in my friendships.

It wasn’t until my college graduation that I finally saw it: Nothing I did would ever be enough for her.

I spent much of my life trying to win my mother’s love. I know now that she did the best she could with what she had, but the little girl I was didn’t get what she needed, and the young woman I was still suffered for that love well into adulthood…I repeated the “love me, please love me” cycle for a long time after leaving my mother’s house. I broke my heart countless times as a result, falling for people who were emotionally unavailable like my mother.

I was still wearing the blue gown with the Columbia University crown stitched onto the lapel. I’d asked my drug dealer then-boyfriend, one of a string of terrible decisions, not to come because I didn’t want to incite my mother. We went to an Italian restaurant not far from campus. Most of my family was there — my aunt, grandmother, sister, cousins. We were eating when I told them that I’d decided not to go to law school, a decision I’ve never regretted. I was going to take a year off to work and figure out my next move. My mother slammed her fork so hard, the entire table shook. She glared at me and said: “Yo sabía que tú no ibas a ‘cer ni mierda con tu vida.”

I’d like to say that this was the moment I stopped trying to please her, but that would be a lie. That wound walks with me always.

***

When my brother died in 2013, I reeled into the darkest place of my life. People say that the death of a loved one is the greatest loss. No one tells you about the griefs that grief will uncover. No one tells you how those griefs will suffocate you.

The grief that came hurtling at me was my mother wound. I had to face it. I had to give it a name: I am an unmothered woman. You can’t take on or heal what you haven’t named. This was the beginning of my healing journey.

I dedicated myself to my healing: I went to therapy, I wrote, I hiked, I worked out, I created art, I did what I needed to be well. It was two years and three months later that I met Katia. I realize now that I was finally ready for a love that I’d never known. A reliable, supportive, I-gotchu love. I’m still learning how to receive it and nurture it. The image of love I’d been taught is so very different from the real thing.

***

The next time I saw my mother was a year later at my cousin’s baby shower. I knew she would be there but I decided to go anyway, with my daughter and Katia.

At first she ignored me and pretended not to care, but once I ran into her alone in the stairwell, she fell apart. My mother is a tiny woman who’s been dealt a hard hand in life. That doesn’t give her a pass.

In that moment, the angry woman was gone, replaced by a frail, broken child.

“I miss my daughter,” she said, smoothing her hand on my cheek. It was the most tender she’d been with me for years. My chest caved. “What happened, Vanessa?”

“I can’t let you hurt me anymore, ma,” I said. I didn’t try to explain myself or defend my partner and our love. It was devastating to see her so broken. I’ve had to remind myself many times since that choosing me was and still is the right thing to do.

She refused to let me introduce her to Katia. “I’m not ready,” she said. Katia was unfazed. She’s been out since she was 16 and doesn’t need my mother’s approval. It’s me who still wants it, though I know that may never happen.

Later, my mother started downing shots of tequila. I watched her, knowing what happens when she does this. When she asked me to take her to the bathroom, she had a crazed, faraway look in her eyes. She was slurring her words and bumping into people. She looked at herself in the bathroom mirror and splashed water on her face. Before long, she was back in that space I remember from childhood, what I’ve learned is a psychotic episode.

She doesn’t remember any of it — how she cried and talked about the man who raped her, “ese degracia’o.” She sobbed when she spoke of my brother. “I miss my son,” she said over and over. Her pain raw and palpable.

Katia held her hair while she threw up. “You remind me so much of Millie,” she said, looking up at Katia, bits of half digested food on her chin.

“But I’m not her,” Katia responded as she held my mother up so she wouldn’t fall into her own vomit.

It’s been three years since that day. I’ve seen my mother only a handful of times since.

***

My mother was a Jehovah’s Witness when she met Millie. She went to the apartment of the sister of an elder, and there was Millie. Mom says she was sitting in a living room filled with women talking and drinking and dancing, when Millie sat next to her. “Do you know what’s going on here?” Millie asked.

I imagine my mother, all of 23 with three children. She had gone through so much in the few years since she’d been in the U.S. She found community, hope, and maybe even redemption in the Jehovah’s Witnesses, but she was still very naive about the world. Millie saw this and started pursuing her.

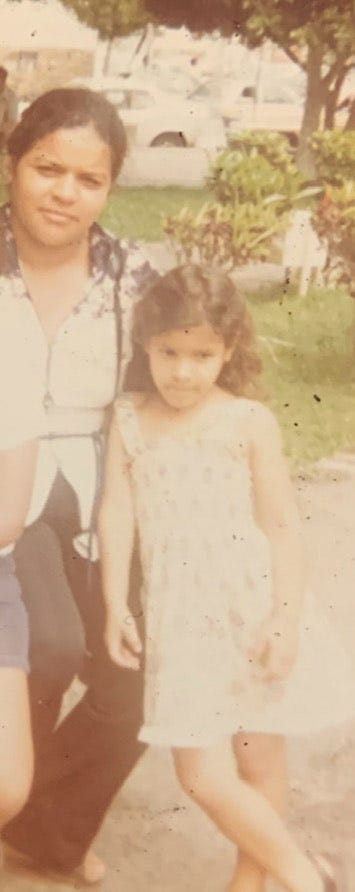

She’d roll up on her bike when we were walking in the street. We’d come home to find Millie hanging out on the stoop of our building. My brother, who was 5, remembered Millie inviting herself in one day. A short while later, she moved in and that December we celebrated our first Christmas. This was Brooklyn, 1978. I was 3 years old.

***

Though my mother and Millie were together throughout my childhood, my mother remained conflicted. I know this because when I was in sixth grade, she put me in Jehovah’s Witness Bible studies classes.

At first, I was ever the serious student. I did all the assignments, read the biblical stories and scriptures, answered the questions, reflected on the lessons, and went to the Kingdom Hall on Sundays. God became my everything. So much so that my sixth grade writing teacher took me aside once and said, “It’s beautiful that you have such a great love for God, Vanessa, but you have to write about something else.”

I kept at it. I imagine that somewhere in my mind, I thought: Maybe this will make Mom love me.

When my brother died in 2013, I reeled into the darkest place of my life. People say that the death of a loved one is the greatest loss. No one tells you about the griefs that grief will uncover. No one tells you how those griefs will suffocate you…The grief that came hurtling at me was my mother wound. I had to face it. I had to give it a name: I am an unmothered woman. You can’t take on or heal what you haven’t named. This was the beginning of my healing journey.

It was all good until I started questioning the teachings. I hadn’t admitted to anyone that my moms were in a lesbian relationship. I didn’t realize it myself until I was in fifth grade and a student told me butch means lesbian.

I think I knew. I think I just didn’t want to know.

When Caroline, the sister who gave us the Bible studies classes, started talking about love and relationships, I asked: “What does the Bible say about love between women?”

Caroline raised her eyebrows. “The Bible says we should all love one another.”

I pushed. “But what does the Bible say about women who love each other like a man and woman love each other?”

Caroline looked around our small living room at the pictures on the walls. Pictures of my family. Pictures of me and Millie and my sister and brother and my mom. “The Bible says it’s a sin.” For homework she had me read the story of Sodom and Gomorrah.

That’s when I started to rebel.

See, the one who loved me, who showed me tenderness, who held me up, who whispered in my ear that I was going to be somebody, was Millie. When I became obsessed with basketball when I was 9, she nailed a bike rim to a splintered board and put it up in the backyard. Then she went out and bought me an official Spalding basketball. When I wanted a bike when I was 10, she went around the neighborhood junkyards and built me a bike out of the pieces she gathered. The body was sparkling purple, one wheel was yellow, the other blue, the seat was a cracked white leather, and the grips, which were peeling away, were a pretty aqua blue. The kids made fun of me and called it Rainbow Bike, but I rode it like it was a king’s chariot.

I was too young to understand the complexities of queerness and what it meant to be gender nonconforming, so when Caroline said what she said about love between women, it was Millie I thought of. Millie was the one who would grab the brim of her Kangol cap and say, “Yo soy butch.” The way she said it, it was like she was dancing salsa but just with her shoulders.

But I couldn’t accept that Millie was sinful. She was the one who loved me.

I started questioning everything Caroline said. If she tried to teach me another portion of the Bible, I went back to Sodom and Gomorrah. I demanded that she explain. When she showed me the scriptures, I shook my head and said, “No. I don’t believe it.”

One day, frustrated and hurt, I yelled, “Well, who wrote the bible and who says God told them to write it?”

Caroline looked at me, her eyes sad and resigned. Without another word, she packed her things and never came back.

Mom beat me that night. She didn’t say why, but I knew.

***

Mom told me once about how Abuela confronted her about being with a woman. They were in a train station when my mother stood up to Abuela. Abuela who didn’t mother her. Abuela who accused her of seducing her husband. “Me ganó la cara,” Mom said. In the scene I imagined, they are in the Wilson Street L train station near where we lived then in Bushwick. They are standing in the turnstile, the wooden bar between them. I hear the roar of the train and I see my mother’s face. The red handprint on her cheek. She is glaring at her mother. That was the day my mother decided to stay with Millie, “por rebeldía.”

My mother thinks I am with Katia to be rebellious. To spite her.

***

“I was never gay, m’ija,” she once told me. “It’s just that Millie was there for me.”

Theirs was a violent and tumultuous relationship, but my mother agrees, “Of all my children, Millie loved you.” So, it’s not completely surprising that once I embraced my queerness, I fell in love with a butch.

***

I saw my mother this past March. I invited her to my house for the first time since Katia and I moved in together three and a half years ago. It was my turn to host the monthly family brunch, a tradition my aunt started a while back.

A few weeks before, Mom hosted the brunch in her house and called to invite me. When we hung up, she texted, “you can invite your friend.” I laughed but didn’t address it. By then she knew Katia and I were engaged and had talked a lot of shit that I ultimately ignored.

That’s the thing about the mother wound, even when you know it’s dangerous, you still hold out hope that the relationship will change. That your mother will one day mother you.

I was too young to understand the complexities of queerness and what it meant to be gender nonconforming, so when Caroline said what she said about love between women, it was Millie I thought of. Millie was the one who would grab the brim of her Kangol cap and say, “Yo soy butch.” The way she said it, it was like she was dancing salsa but just with her shoulders.

We had a good time at the brunch in her house. My mother was decent, even kind. She and Katia talked and joked. Katia was sick with a bad cold and had to leave early. Mom sent me home with Tupperware full of food for Katia. The next day, Mom texted to ask how Katia was doing.

It was progress. So when it was my turn to host brunch, I invited my mother.

The day started with drama. She said she lost her keys and couldn’t come. I was distraught. I had doña clean my house the week leading up to it. Mopping and wiping and moving furniture and ensuring my house was in tip-top condition. I didn’t say this aloud but I know why — I wanted my mother’s approval.

I woke up super early to cook a lavish meal. We bought steaks to grill on the deck. I had Katia buy champagne and gallons of orange juice to make mimosas.

Mom came in hours late, after we’d all eaten and had several drinks. She walked in criticizing. She didn’t like that I lived on a hill. She didn’t like where I live because you have to walk down a path at the side of the house to get to the entryway then up a narrow set of stairs to get to our apartment on the third floor. She said I pay way too much rent. “Why don’t you buy a house already?” She told me to close my writing room door because she didn’t like the pictures I had posted. This was the room I cleaned the deepest, that I was most excited to show her. I shook my head. “You can move,” I said and kept talking to the family.

She said my plants needed watering. I needed to change the soil. She was surprised I had a bag of soil on hand. She showed me how to repot one of them. The plant has thrived since she put her hands on it.

She wasn’t there two hours before it happened. The topic of the wedding came up and I started talking excitedly about our plans when she demanded that I stop. She said it was disrespectful of me to discuss it in front of her. She called me malcriada. It was then that I saw in real time all the healing I’ve done over the past few years. I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t flip out. “You cannot take away my joy,” I said.

She stormed out. I haven’t seen or spoken to her much since.

I married Katia on May 10th, surrounded by the people who love and support us — Katia’s family, her mom, siblings, a few cousins; my chosen family including my sister friends. my mother’s sister and brother, and my abuela.

Yes, I wish my mother was there.

Yes, I wish my mother would accept my relationship.

Yes, I wish she could mother me, but the fact is that she can’t, and though it pains me, I’ve gone no-contact for now.

That’s the thing about the mother wound, even when you know it’s dangerous, you still hold out hope that the relationship will change. That your mother will one day mother you.

It hurts to not have her in my life, but it hurts more when she’s present and in my life.

Thankfully, I’ve learned that I can make something beautiful out of my suffering: I can start the Writing the Mother Wound Movement, and I can help people write and publish their stories about their fraught relationships with their mothers.

The greatest thing that has come out of this work, however, is this: My daughter is not unmothered. She walked me down the aisle, though she made it clear: “I’m not giving you away, but I’m willing to share you.”

This is the love I’m reclaiming. This is how I’ve learned to mother myself.

As a 55 year old woman with a mother who was more cruel than not, I loved reading every word of this.

That "mother wound" seeps into every part of your life like you wrote. I too, did the "pick me, love me" dance with far too many relationships. Why? Because it felt normal to beat my head against a cold wall of motherlessness.

I write all the time and it's too painful to write about her. I struggled with her eulogy last year. How do I honor a mother who didn't honor me?

“This time, I have her blessing.” What a powerful intro and courageous reckoning with the complex layers of mother/daughter relationship. Glad you’re teaching from this. I’ve slowly been trying to understand the nuances of how we tell stories about our inheritances, good, bad, whole. I feel it’s beautiful work.