When I was in my early twenties and starting out as a writer, I received assorted bits of advice, some good, some bad.

The good: a journalist at Newsday—where I had an internship as a reporter on the arts desk the summer of 1986—told me not to waste my time or go into debt pursuing a Masters in Journalism. “You’ll learn much more on the job, and you’ll get paid while you’re doing it,” she told me. I think this remains sound. While journalism has gotten way more competitive since then, I know too many writers who took on massive loans for “J-school,” only to have difficulty finding jobs with high enough salaries to pay those loans back—if they can find jobs at all.

The bad: a woman named Helen, who ran an editorial employment agency through which I sought jobs after college, told me that when I went on interviews at magazines, newspapers, and publishing houses, I should leave at home the fairly impressive clips I’d garnered at Newsday and elsewhere before graduation. Otherwise, she cautioned, I’d seem too ambitious and unwilling to do the kind of grunt work that came with entry-level positions.

In hindsight, it’s probably no surprise that hiding my achievements didn’t help me land the kinds of jobs I wanted. I mean, how counterintuitive was that advice? Please do highlight your achievements when applying to jobs! And don’t listen to anyone who suggests otherwise. What Helen suggested next, though, had an even bigger negative impact on my career path: that I give up on trying to write for consumer publications (mainstream periodicals read by regular people) for the foreseeable future, and instead get a job writing for a trade publication (a business periodical aimed at people who worked in a particular field).

She said that sometimes the best way into the work you wanted was through a side door—taking jobs that weren’t quite the ones you wanted, but adjacent to them. From there, you could finagle your way into better positions. She added that if I really loved writing, I should love doing it about any subject, for any audience. That might be okay to do early, early in your writing career, before you’ve gotten any experience and are trying to get your feet wet. But I had come to her with some solid clips. Even if you don’t, I’m not sure I’d advise doing only that for too long if you’re trying to write creatively. You might find yourself burned out and sidelined, the way I was, in such a way that it’s difficult to pivot back to the kind of writing you’d prefer to do.

I was so young and impressionable. It didn’t occur to me that Helen wasn’t my writing mentor, she was an employment agency owner, a business person, with particular jobs to fill. She didn’t have my best interests at heart. Unfortunately, listening to her advice contributed to a nine-year detour away from my tandem dreams of covering arts and culture and publishing personal essays and memoir. I got stuck in a trade publishing rut that was difficult to get out of, because I had become labeled a trade writer.

What I learned from this too late is that you need to carefully vet the people from whom you take career advice—certainly more carefully than I did in those days. Many years later, an accountant suggested that before taking advice of any kind from anyone, you should find out whether they had any financial stake in what they were suggesting to you. In hindsight, Helen had a stake in diverting me away from my dreams; she had trade magazine positions to fill.

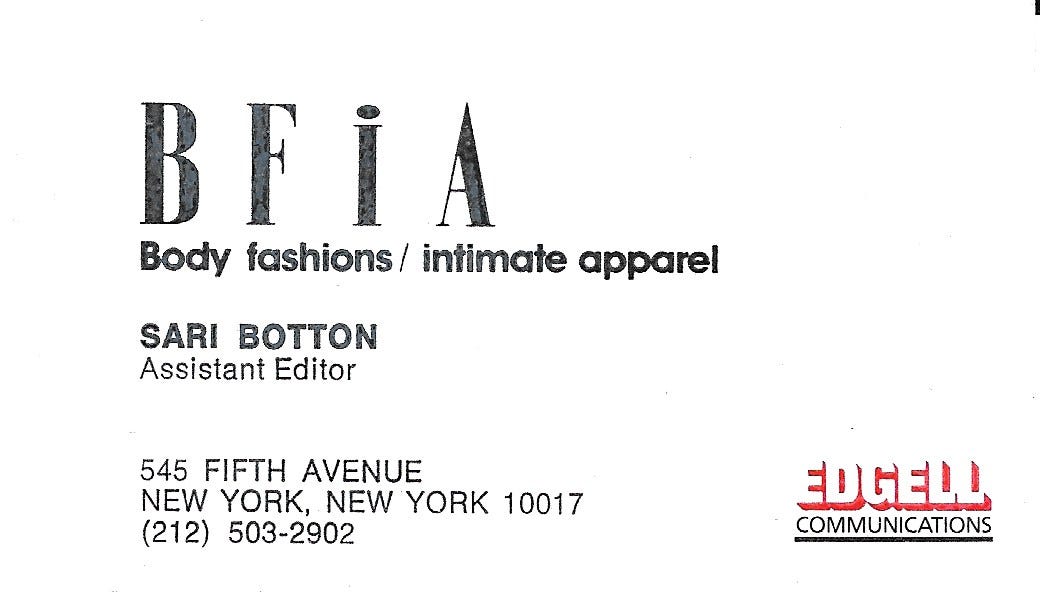

The first interview she sent me on in the summer of 1987, at a magazine covering the pest control industry—as in, exterminators—should have been a clue. They offered me the job, and despite feeling deeply depressed by the prospect of covering the ins and outs of the insecticide business, in the absence of other offers, I was prepared to accept it. Just before I signed on, though, I got a better offer (which obviously wasn’t saying much): an assistant editor/reporter position at Body Fashions/Intimate Apparel (BF/IA) a trade magazine covering the women’s underwear business, for $17,500.

I look back tenderly on 22-year-old me, the cub reporter who took her job at BF/IA verrrry seriously. It might not have been the arts pages of the New York Times, or even my alma mater, Newsday, but I earnestly acted as if it were. I took on extra assignments on my own time, and applied my arts writer flair to them. I wrote a long essay—my first longform!—drawing connections between Madonna’s penchant for wearing bustiers and bras publicly and the Rococo period of art, when Jean-Honoré Fragonard painted The (Happy Accidents of the) Swing, in which a woman’s long bloomers peek out at the viewer.

When BF/IA flew me out to a bra-fitting promotion at a Marshall Fields in Chicago sponsored by a company that manufactured underwire, I looked to it as an opportunity to build my chops as a journalist. By gum, I was going to get the bottom of what percentage of women wore the wrong size bra, and why!

Aside from those two assignments, though, I found the job tedious and stifling.

From there, I landed at assorted other trades—Women’s Wear Daily; Home Furnishings Network, where I had the weirdest combination of beats: decorative pillows, luxury linens, air purifiers, and personal alarms, like the one Tonya Harding had deployed when she was attacked in a parking lot in the early 90s. At 25 I became the editor-in-chief at Fashion Jewelry Plus!, a joke of a publication owned by a trade show company, really more of a trade show directory. I freelanced for others, including even—somehow—The Newspaper of Cardiology, despite zero background in medicine.

I suppose that would have made Helen proud: I had truly learned to apply my writing abilities to any random subject. The advantage to that capability, if there was one, might have been that it prepared me for one of many turns that lay ahead on my wayward career path: ghostwriting other people’s books, on every topic under the sun, including: children with learning disabilities, herbal medicine, home birth midwifery, what it took to stop a mass shooting, biographies of Tin Pan Alley musicians, and more.

On the bright side, I had developed a skill, and I knew how to implement it in a versatile way. I could use it to survive. Given how unpredictable media and publishing have grown, it’s not altogether a bad thing to know how to use your writing and editing skills flexibly, wherever scarce opportunities arise.

There was a disadvantage, too though: somewhere along the way I realized I wanted to write my own books instead, to publish more of my own personal writing, and all the draining day jobs and gigs as a writer that I kept collecting were getting in the way of that. There’s only so much writing one brain can manage, and it’s important to know when to draw the line, when to say, “I’m doing too much of this thing that I’m good at for work I don’t care about, and it’s taking me too far afield from the work I really want to do.” This is not always easy, especially when you are financially unstable, as I have consistently been all my life. But there comes a time when you must find a way to choose yourself and your own writing; to say “no” to random wordsmithing so that you can say “yes” to yourself.

In 1992, the year I turned 27, I took the first tiny steps in that direction. I went through a major personal reckoning. (A psychic blamed my Saturn return.) I left the marriage I’d entered three years before, along with our suburban home for the city. Nothing else in my life felt right to me, either, including the writing and editing work I was doing at trade magazines. The prior year, I’d taken a personal essay workshop at NYU, and instantly I knew: this is what I want to do.

But how could I make that switch, I wondered? A woman I worked with at one of the trade magazines was pursuing her MFA in poetry on the side at Sarah Lawrence. On her suggestion I applied (there, and elsewhere) and got in. I was so thrilled, I neglected to figure out a few important details, such as how I’d pay for an MFA, and how I’d manage the workload (and the commute to and from Bronxville) while working a fulltime job.

I knew I could use a portion of my small divorce settlement to pay for the first semester, part-time. But what would I do after that? (In my memoir, you can read about one of the crazy things I tried.)

I dropped out of the MFA program, and a year later tried again at much less pricey City College. Once more, though, I struggled to balance a full-time job as a reporter with my creative writing pursuits. There were just too many words swirling through my head, in too many different situations. I dropped out of school once more. It broke my heart, and left me feeling defeated. Since then, I’ve felt regretful that I didn’t keep going with my MFA, and finish it (although I am glad I’m not saddled with the associated massive debt). And I’ve often wondered whether it would have been easier to if I’d had a different kind of day job, one where I wasn’t working all day with words and sentences that meant nothing to me.

I could give you a guided tour through all the subsequent turns in my circuitous, chaotic writing and editing career (you can read more about it in my memoir, And You May Find Yourself…) but instead I’ll just spell out for you what I’ve finally realized after all these years: I wish someone had told me early on that I could have a day job in a different field entirely, and on the side, still become the kind of writer I really wanted to be—a creative writer. I wish someone had warned me that writing just anything for a living, including so many things I couldn’t have cared less about, would drain me, mentally and creatively, and keep me from producing enough of the essays, memoir, and fiction that I realized, thirty years ago, were my passion.

If you are in a similar place in your career—working for trade publications or using words in an utterly uninteresting, mercenary way, and you’re young enough to learn some other skills and start out in a new field, let me tell it to you straight: Do something else for a living, and pursue your writing dreams on the side. It will add to your life experience, and your life experience informs your creative writing. Don’t let a different day job stop you from feeling like a writer. If you’re a writer, it’s because you write—in the early morning, late at night, on weekends, on the subway—not because you climb ladders at editorial or media concerns that take you nowhere.

Of course, this advice might not ring true for everyone. Some might find that working with words all day doesn’t interfere with their creativity. And for those who genuinely want to pursue full-time jobs in publishing or media, climbing those ladders might pay off. But for those of you who want to prioritize your own writing projects while supporting yourself with work that doesn’t drain you creatively, this is the advice I wish I knew.

The advice Helen gave me, to just take any writing job I could get, on any subject, led me astray. Okay, maybe it helped me develop some of my writing chops, rendering me a more versatile wordsmith. But after wandering through the trenches of trade publishing for a few years, then ghostwriting, followed by copywriting gigs for websites like USPS.com (I know more about Click-n-Ship™ than I ever bargained for), then more horrible ghostwriting—and always struggling financially—I’ve come to wish that years ago, I’d learned some other skills, pursued some other field, one that paid better, and more importantly, left me with the bandwidth I needed to focus on the writing that mattered more to me than anything else in the world. If you are able to do that, do it! If I could, I would.

But at 57, it’s now probably too late for me to start anew in another arena. These days I make much of my living reading and responding to other people’s writing. While I love this work, with our industry in freefall, I have to keep doing more of it for less money. It takes a mental and emotional toll, and it detracts from my own writing. Even though I wish I had more time to write, I worry constantly that someday my opportunities to work as an editor and teacher will dry up completely. Then what will I do?

Sometimes younger aspiring writers ask me for advice, and I often suggest that they try to make their living some other way, while pursuing writing on the side. They tend not to like that answer, and I probably wouldn’t have liked it if someone had suggested it to me before I got going in my career. But from where I stand now, that looks like a smarter bet, and an option I wish I had now.

Doing something that makes more money and doesn’t turn you into a zombie is something I often say I would tell my younger self. That girl knew she wanted to be a journalist. She was for a long time but working with the wrong people will drain you and burn you out.

This is good stuff! ❤️