The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #45: Colleen Long & Rebecca Little

"In the middle of our research Roe was overturned and so it took on a critical urgency as so many people who never intended to end a pregnancy are now caught up in the post-Roe medical landscape."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

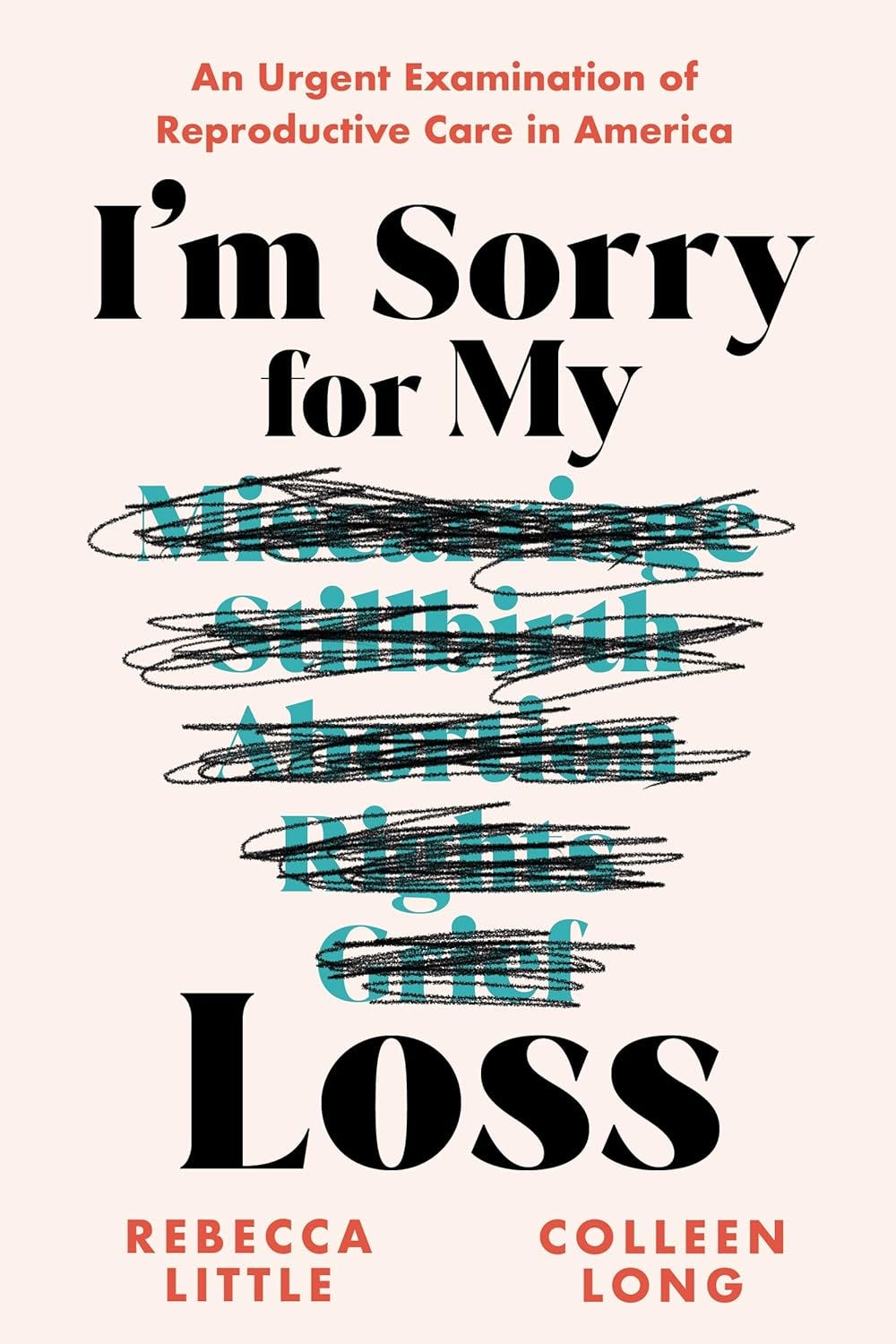

Here’s the 45th installment, featuring Colleen Long and Rebecca Little, co-authors of “I’m Sorry for My Loss: An Urgent Examination of Reproductive Care in America.” -Sari Botton

Colleen Long is a writer and a veteran journalist who has covered some of the most important news in the nation over the past 20 years, including crime and courts in New York City, immigration in the Trump era, and the 2020 and 2024 presidential elections.

Rebecca Little is an accomplished Chicago-based freelance writer and former contributing editor for Chicago Magazine. She has written for The Chicago Tribune, Chicago Parent, WBEZ, Zagat, Google, The Irish Times, and Crains Chicago Business, among other publications, as well as many corporate and university clients. She has written about education, parenting, home design, style, politics, travel and pop culture. She has a master of science in journalism from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

Colleen: I have been writing professionally since I was 22 and non-professionally since I was eight. And now I’m 46.

Rebecca: I’m 46. I’ve been writing professionally since I was 22, and non-professionally since I was in first or second grade. I recently found my first “book,” an adventure story with a very loose grasp of geography.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

I’m Sorry for My Loss: An Urgent Examination of Reproductive Care in America was published September 24th, 2024.

What number book is this for you?

Colleen: One!

Rebecca: First!

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

Colleen: Non-fiction, because while it contains a bit of our own personal stories, it’s a work of journalism.

Rebecca: It’s nonfiction, a researched and reported work of journalism, but we employ authorial intrusion to be the reader’s guide throughout the book. We also interject our own experiences with pregnancy loss, so it has some elements of memoir. We decided to make ourselves, two friends and journalists, the guides through this very difficult subject.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Colleen: The book is an investigation of pregnancy loss; we sought to understand why, when it's so common, so many people feel so unprepared, ashamed and alone. In the middle of our research, Roe was overturned and so it took on a critical urgency as so many people who never intended to end a pregnancy are now caught up in the post-Roe medical landscape. They’re suffering increasingly perilous medical care. We are childhood friends who both grew up to be journalists, and we both have personal experience with this.

Rebecca: The book is an investigation of pregnancy loss—miscarriages, stillbirths, and terminations for medical reasons. We wanted to find out why so many people feel unprepared, isolated, and ashamed when they have these losses, given how common they are. Roe was overturned in the middle of our research, so it both expanded the reporting and took on a critical urgency as many people who never intended to end a pregnancy are now caught up in the post-Roe medical landscape. We are childhood friends who both grew up to be journalists, who have both also experienced pregnancy losses after 20 weeks, and we decided to write the book we wish we had when we were going through it. This is not the book you read in the fog of grief. This is the book you read months or years out when you think, why was my experience like that?

The book is an investigation of pregnancy loss; we sought to understand why, when it's so common, so many people feel so unprepared, ashamed and alone. - Colleen Long

Roe was overturned in the middle of our research, so it both expanded the reporting and took on a critical urgency as many people who never intended to end a pregnancy are now caught up in the post-Roe medical landscape. - Rebecca Little

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

Colleen: As you’ll read in the book, it began with text messages as both Rebecca and I sought to understand what had happened to us, and in the middle of the pandemic as everyone in the world was reevaluating their lives, I thought the thing I really wanted to do was right a book about this. I heard the oral arguments in the Dobbs case and suspected reproductive health would be front-and-center. So we started to form a proposal and look for agents. We knew we needed the tone to be right, so we worked very hard on crafting the voice of the book, we understood that would be the selling point.

Rebecca: I studied English and women’s studies in college, and I was the editor-in-chief of the college newspaper. My first job out of college was at a local newspaper in the Chicago area, and then I attended the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University for graduate school. From there, I worked at Chicago magazine and the Chicago Tribune for years as a full-time freelancer, as well as writing for other publications and corporate clients. My favorite thing is to write personal essays, and I started to work on those more after my pregnancy losses. Colleen is also a journalist, and we decided to combine our professional talents (and personal tendency toward gallows humor) to write this book—not a grief manual, not a memoir—but a book that was deeply reported and represented many voices and viewpoints to explain why America is so bad at dealing with all aspects of pregnancy loss.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

Colleen: For me, two things. One, waiting to see whether our agents (who are fantastically supportive and wonderful) would take us on. We knew we could sell it if we got the right agents. And the second thing is going on right now: I worry that it will be dismissed or relegated to the “lady” stacks because it is a book about giving birth, something traditionally female. I want it to be seen as a true work of solid contemporary journalism, not as a “lady reporter” book though we are proud lady reporters. But you know what I mean. Fingers crossed.

Rebecca: The interviews where we talked with birthing parents about their losses were almost sacred. They were emotional and personal, and their trust meant so much to us. Sometimes that was hard, but it also convinced us that what we were doing was important. There were definitely times as chapters evolved where we couldn’t find a home for a quote or a story, but knew it needed to be included, and that could be really frustrating. There was so much ground to cover, and we wanted to make it so comprehensive, that organizing it all was sometimes a challenge. We ended up finding the perfect narrative spot for everything, but the process included us putting our heads down on the kitchen table in despair for long stretches of time. You know, writing.l

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

Colleen: We interviewed more than 100 people who suffered some kind of loss, and we let them choose how they wanted to be identified because of the extremely personal nature of their stories. Some used their first names, a few chose pseudonyms. We fact-checked and had them read their parts so that we could ensure accuracy. We did make factual changes but, as with most journalism, we don’t allow sources to dictate the way the book was written or organized.

Rebecca: I mostly identified the people close to me by relationship rather than using names, and of course ran the whole book by my husband because I talk about our personal pregnancy losses. (He was very supportive.) As far as the non-relatives, we interviewed more than 100 people who suffered some kind of loss, and we let them choose how they wanted to be identified because of the extremely personal nature of their stories. Some used their first names, a few chose pseudonyms. We fact-checked their stories with them so that we could ensure accuracy. We did make factual changes but, as with most journalism, we don’t allow sources to dictate the way the book is written or organized.

We are childhood friends who both grew up to be journalists, who have both also experienced pregnancy losses after 20 weeks, and we decided to write the book we wish we had when we were going through it. - Rebecca Little

As you’ll read in the book, it began with text messages as both Rebecca and I sought to understand what had happened to us, and in the middle of the pandemic as everyone in the world was reevaluating their lives, I thought the thing I really wanted to do was right a book about this. - Colleen Long

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

Colleen: I really thought a lot about Mary Roach, whose work I deeply admire and who once answered an email I wrote to her when I was in my 20s about advice on how to write a book. Her specialty is making palatable topics that are taboo or at the least very difficult to talk about. And she deploys humor in a surgical way to cut the sadness or to lighten the mood. We really sought to do that, too. And then of course Joan Didion, because she in her nonfiction was able to capture something accurately and write personally about it but also somehow remark ON it, even as it was happening to her. The observer-within-the-observer was also something we sought to model. We wanted everyone to be as sad, angry, shocked, delighted as we were reporting it.

Rebecca: We really looked to Mary Roach’s books—she takes difficult topics and makes them accessible and entertaining. Other nonfiction writers I love are Barbara Ehrenreich, Joan Didion, Nora Ephron, David Sedaris, Bill Bryson and Caitlin Moran. A mix of reporting, dry prose and wry observation is my favorite combination.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Colleen: People told us that you must be really interested in your subject, and that’s true. You really do. You must care very deeply about the thing, because otherwise there’s no point in going through any of this because it is challenging and humbling. But I would also say if you care, do not give up. Keep trying. Also, my friend Jon Lemire, who wrote the book “The Big Lie” gave me the best advice of anyone. You just must work on it a little bit, every night. It has to become routine.

Rebecca: The best plan is to make a roadmap and then break that down into smaller pieces. For us, the proposal became the basic outline of what we wanted to research. Then we did the research, took notes, and organized those into our subtopics. As we interviewed, we loosely placed what we learned under those broader categories, so we knew what we had, and those interviews also informed new areas for us to research and ask other sources about. These broader topics then became multiple, more specific chapters. I’m making it sound more rigid than it was in practice, but it really helped not to just have a mound of research to try to organize at the end. If you knock something off that outline every day, eventually you have a book.

In Michelle Obama’s memoir, she has a great line about fighting imposter syndrome, where she says, “I have been at every powerful table you can think of…they are not that smart.” She’s specifically talking about the tendency for women to count themselves out, or think they aren’t qualified, but I think it works here, too. Plenty of other people have written books. Why not you?

What do you love about writing?

Colleen: I think I communicate best in writing, so I love that feeling – of being in command of what I am trying to say and thinking (or hoping I guess) that people will actually understand it. I also really love how a good bit of writing, fiction, non-fiction, memoir whatever it is – it just makes you think and feel so strongly.

Rebecca: I love when it’s effortless, when everything pours out and it makes perfect sense and just works. Every writer probably chases that feeling, that “flow,” even though it’s not the daily experience. I also love getting a great idea and knowing just how to execute it. That’s living the dream.

What frustrates you about writing?

Colleen: It is so fucking hard. Writing is so hard. And it feels so futile and lonely sometimes.

Rebecca: I get frustrated when I am circling an idea but just can’t get there. I always get there eventually, but sometimes the process is a slog. The slog days make me wish I had any other marketable skills, but alas, writing is all I have to offer. In a broader sense, I am frustrated that writing as a profession is so underpaid and undervalued.

What about writing surprises you?

Colleen: I had these moments where I was lost in a chapter and suddenly the way through revealed itself, it was like all of I sudden I very visually saw the path forward, or I visualized taking a left or a right into a new place. Then I would mentally look behind and think, oh yes, I know where I am going and I know where I have been. There’s this Fiona Apple song, “Extraordinary Machine,” and she sings in it: “I can’t help it the road just rolls out behind me.” I felt that writing and it was such a surprise. To think, oh yes! That’s where I was and here’s where I need to go.

Rebecca: It always surprises me when something becomes clear that I hadn’t expected before I sat down to write; when you think the story is going one way only to realize it’s so much better if it zags. I think non-writers find this strange, because how can a writer be surprised by what they’re writing? Is a poltergeist involved? But every writer recognizes this feeling, and it’s the best. (Although, to be clear, I wouldn’t say no to an author poltergeist to do some of the heavy lifting from time to time. A chore ghost would also be very welcome.)

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

Colleen: Yes. Because I am a full-time journalist, I do my day job, then make dinner and put the kids to bed and then write for a few hours at night. The mental post-dinner break really helps me refocus my mind. Though I routinely fight the urge to go downstairs and watch TV.

Rebecca: My writing practice is less informed by my own natural rhythms than the hours of the school day out of necessity. I tend to use the mornings to respond to emails and do life admin, then start writing when all those fires have been extinguished. I work until 330p, then shift to kid time until 9p, and then work at night if I’m on a roll or I’m under a deadline.

We interviewed more than 100 people who suffered some kind of loss, and we let them choose how they wanted to be identified because of the extremely personal nature of their stories. Some used their first names, a few chose pseudonyms. We fact-checked and had them read their parts so that we could ensure accuracy. We did make factual changes but, as with most journalism, we don’t allow sources to dictate the way the book was written or organized. - Colleen Long

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

Colleen: I love to sing, but I haven’t been able to find the time to get involved in anything formal.

Rebecca: I love to thrift and decorate, and I also keep a pretty detailed diary. I started the diary as a way to keep track of the funny things my kids said and did, and then it became a time capsule of each year of my life. Those diaries have then informed essays I have written professionally.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

Colleen: I am working on a TV pilot for a show based off my job as a New York City crime reporter, and we are going to launch the research for our second book at the start of the new year!

Rebecca: I am in the process of writing a book of personal essays, launching a Substack, and Colleen and I start working on our next book in the new year.

I am excited to read your book. After a dear friend and journalist colleague lost a baby to a stillbirth, she wrote a memoir called Life Touches Life by Lorraine Ash, which took her years to find a publisher for. It opened my eyes to how many women had pregnancies that ended in miscarriage or stillbirth, or who needed extreme medical care.

Just yesterday, a longtime friend said she had lost a boy to stillbirth and at the time, 40 plus years ago, there was no one to talk to about the loss. Books like yours and Lorraine’s are part of the new conversations about what it means to be a woman in a cultUre that shames those whose bodies cannot hold a pregnancy, through no fault except of the realties of human pregnancies. medically, one out of five pregnancies end in natural miscarriage or stillbirth, or other heartbreaking, life threatening complications. Yet, woman were shamed or guilted into never talking about their experiences. I hope your book will add to the body of information that will help end the stigma around imperfect pregnancies.