A Storybook Childhood

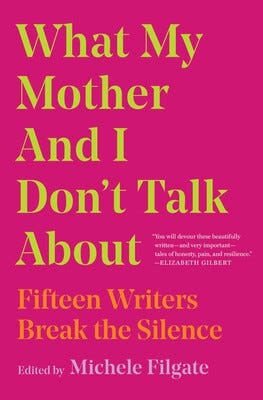

An excerpt of "What My Father and I Don't Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence." PLUS a video interview with Michele Filgate, editor of the anthology.

Readers,

Today we have an excerpt of ’s new anthology, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence, a moving essay by . It appears below this section. ⬇️

The book is fantastic and includes contributions from Filgate, Rakoff, Andrew Altschul, Alex Marzano-Lesnevich, , , Jaquira Díaz, , , , Tomás Q. Morín, , , , , and

It’s a follow-up to Filgate’s first anthology, What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About: Fifteen Writers Break the Silence, in which I have an essay, which was reprinted at Catapult (RIP).That first book came about after I published Filgate’s essay, “What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About” at Longreads, in October of 2017.

Recently I talked with Filgate about the new anthology, and her own essay in it. Here’s our interview:

Tonight at 6pm at Harvard Bookstore in Cambridge, Mass., Filgate will be joined by Rakoff and Kelly McMasters on a ticketed panel moderated by Andre Debus III. I highly recommend attending if you’re in the Boston area!

Below is Joanna Rakoff’s essay. Thanks for reading, and for all your support! -

A Storybook Childhood

by

When my son was little, I spent my days pushing his stroller through the narrow streets of the Lower East Side, carving a path across Grand and up Orchard, stopping in my favorite shops for a bialy or a pickle. The proprietors all knew my name and preferences—poppy seed, half sour—from my days walking these streets with my father, who’d grown up in the boxy, postwar apartment I now inhabited. And as I strolled with Coleman, the neighborhood’s trademark wind pushing forcefully at my face, I pointed out the sites of significance in my father’s life: the high school from which he’d graduated at fourteen; the corner on which his nemesis painted “Elmer Stinks”; the restaurants in which he’d eaten verboten shrimp chow mein. Every site held a story—the Forward building, where his uncle was shot by the police at a union rally!—and these stories had become so much a part of me that I often forgot they weren’t my own memories but my father’s.

It never occurred to me, not once, not ever, that they might not be true.

It never occurred to me that my father survived through the stories he told. Nor that I did, too. Nor that I was teaching my son—and later, my daughters—to do the same.

***

By the time my son was born, a mysterious neurological disorder made it difficult for my father to walk ten feet, but the moment he arrived on Grand Street he summoned the energy to stroll to his father’s synagogue on Norfolk, narrating the way, as he had in my youth, his stories still so vivid I could see his aunts and uncles and cousins popping out of their hat shops on Allen or their union meetings at the Henry Street Settlement to give him a hug. My father had not had an easy childhood, but when he told me about his youth he turned even the most brutal beating into a punchline, laughing so hard at his own jokes we’d need to stop so he could catch his breath.

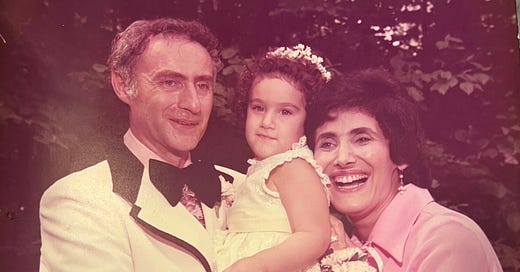

My mother never accompanied us on our walks, as she loathed the grimy streets that produced the man she loved.“She had a storybook childhood,” my father often told me, my mother nodding and smiling in agreement, thinking—I presumed—about the her bucolic early life in Gloversville, a small city in the Adirondacks, where her family owned a bustling restaurant at the center of town. Her family had come not from the shtetl—like my father’s—but from Warsaw, where they owned a flourishing saddlery; they’d brought their fortune to the U.S. in three and four karat diamonds—sewn into their coat linings—one of which my mother wore in a simple Tiffany setting as her engagement ring, because my father, of course, had been too poor to buy her something similar.

While my father shared a foldout couch with his brother in the living room of his family’s one-bedroom apartment, my mother lounged around a grand Victorian, alongside her doting maternal grandparents and uncles, with frequent visits from her kindly aunts, Lee and Fritzi, who’d moved down to the city, but returned frequently to lavish her with gifts and attention. While my father suffered through Manhattan’s most underfunded public schools, my mother flourished at a tony girls' school. While he saved pennies to buy crackers out of barrels, she snowshoed to school and skated on frozen ponds and sipped milkshakes at the long marble counter of her family’s restaurant. “Poor girl, she had to learn to cook and clean when she married me,” my father often joked. “Well, yes,” my mother would respond, with a close smile. “All our meals came from the restaurant. My grandmother never even turned on the stove.”

The Storybook Childhood, described by my parents in tandem, a practiced routine, proved so enticing to me, I never inquired about certain inconsistencies—where, for instance, was my Grandma Pearl, my mother’s mother, in these tales? Nor did I notice that they failed to elicit, from my mother, even a shred of laughter. Not even, really, a smile.

***

One rainy afternoon, at fourteen or so, I opened the teak cabinet in our family room and a slim, unfamiliar volume popped out. A yearbook. “Walton,” embossed in gold on the crumbling cover. Walton. It took a moment to place the name—my mother’s tony girls' school—and another to find her senior portrait, a full body shot, my mother stunning and chic, her inky hair in soft waves. As I flipped through, I noticed something strange: All the senior portraits appeared to be taken in a city. I turned back to the opening page: Walton High School, Bronx, NY.

Bronx? The Bronx?

At dinner, I gathered the strength to ask my mother about the yearbook. “Yes,” she said, her eyes focused on the paprika-dusted sole she’d immaculately prepared. “I went to high school in the city. I’m sure I’ve told you that.”

My father gave me a warning look and shook his head gently from side to side. Later that evening, as I drafted a paper on Thoreau, he appeared in my doorway. “Your mom’s not like me,” he said, leaning his thin shoulder against the frame. I nodded, confused; I had always thought my parents a discrete unit, symbiotic, identical, rather than two separate entities. Were they different? “You can ask me anything!” he went on. “I’ll tell you all the embarrassing things that happened to me when I was a stupid kid.” He burst into laughter at the mere thought of his childhood antics, then sighed heavily. “But, your mother—” he paused and looked at me, that same warning gaze, “doesn’t like to talk about the past.”

My mother didn’t like to talk about the past. How had I never realized this? It was true. All conversations with my mother revolved around the future: What would we eat for dinner? Where would we find a dress for Edwin’s wedding? Where might we travel in August?

Yes. This was the difference between my parents: My mother avoided the past and my father seemed to live in it.

“So do me a favor? Don’t ask her about her childhood.” he said, his voice steely beneath his habitual smile.

I nodded, for this seemed a small ask.

***

But small asks can have large repercussions. Silence always carries a cost. I became afraid to ask my mother anything.. And afraid to tell her anything, too, anything other than veal piccata for dinner and I can wear the black Martine Sitbon and let’s go to Candlewood Lake.

I pulled away from her, removed my real self from her.

Or maybe that’s not what happened. Maybe she sensed the questions roiling beneath the surface? Maybe she removed herself from me to prohibit the possibility, ever, of my asking?

****

One night, not long after I finished college, my father and I drove to my grandmother’s apartment—a few years before she died, leaving it to me—and as I watched the East River spiraling darkly to our left, I found myself saying, though I knew the words weren’t right, “I don’t understand why mom hates me so much.”

For some time, we sat in silence, spinning past the glimmering water, and then my father said, “Your mom doesn’t want me to tell you this—She doesn’t want you to feel sorry for her or for her past to affect you, but—” He sighed and laughed his habitual laugh. “She was a bastard.” My breath quickened at the sound of this ugly word in my father’s gentle voice.

“A bastard?” I asked, my voice tentative and strange.

“Not exactly a bastard, but she didn’t have a father. Or, her father abandoned your Grandma Pearl in the hospital. Right after your mother was born. Pearl woke up and he was gone. She never saw him again.”

“In Gloversville?” I asked.

“In New York,” my father explained. “But she brought your mom back to Gloversville. She had no choice. A single mother in those days—” he paused. “It was hard for her in Gloversville, though. She was a pariah. So she left your mother with her parents and her brothers, Uncle Sam and Uncle Jake,” my father said, his voice now hoarse with emotion in a manner that frightened me. “It was very hard for your mom, too.”

“And so she went to,” I asked, tentatively, trying to piece together this story and failing. “The Bronx?”

“She did,” my father confirmed. “Uncle Jake married a woman named Rose. Your mom was about twelve. Rose couldn’t stand your mother. I think she was jealous. Of how much Jake loved your mom.”

“Jealous?” I asked, cautiously, my own voice now raspy with the threat of tears.

“Yes, yes.” My father shrugged. “Or that’s one story. I think there was also some trouble with her other uncle.”

Suddenly, I realized that though I’d heard a bit about her uncles, I’d never met them. Which perhaps wouldn’t be unusual except that she spoke to her aunts nearly every day, and we visited them so frequently, I could still, to this day, describe to you every knick-knack on their shelves and the specific notes of their perfumes. My heart began beating too heavily in my chest and I willed him not to go on. I did not, I realized, want to know the truth. I wanted the Storybook Childhood. Even if it meant my mother and me, forever, keeping each other at arm’s length. Why? I asked myself, enraged by my cowardliness, my coldness. Because I could not bear to hear the extent of the pain beneath my mother’s perfectly knotted Leger scarves? Or because I knew that it came with an assurance of silence? Silence which would not thaw the chill between my mother and me but only exacerbate it?

The Storybook Childhood, described by my parents in tandem, a practiced routine, proved so enticing to me, I never inquired about certain inconsistencies—where, for instance, was my Grandma Pearl, my mother’s mother, in these tales? Nor did I notice that they failed to elicit, from my mother, even a shred of laughter. Not even, really, a smile.

“Your mom was sent to live with Aunt Lee, but she couldn’t handle your mom.” He looked at me, a hint of his usual mirth at the corners of his mouth. “Your mom had been very spoiled in Gloversville. And I guess she threw tantrums if she didn’t get exactly what she wanted. She’d just scream and scream. So, they sent her to Aunt Fritzi, who laid down the law. Apparently, she locked her in a closet for an entire day.” My father shrugged. “Okay,” he said, as we exited the Drive onto Grand. “That’s enough of this sad stuff. But listen. Don’t, under any circumstances, ask your mother about any of this. Do you hear me?” I nodded, my heart beating rapidly. My father rarely got angry but when he did, it was terrifying. “Your mother put all this behind her when we got married. She’s a different person now. Don’t ever bring this up with her.”

***

I never did. Never. Not ever.

But one afternoon, a few years after my father’s death, my mother and I had a rare afternoon alone at her kitchen table. “You know,” she said, breaking off pieces of rich, buttery pound cake, “you were so lucky to have Daddy.” I sat up straighter, astonished, for my mother, still, never spoke of the past. Nor did she utter grand statements or what she considered “treacly” sentiments.

“I know,” I said, smiling, but she wasn’t listening.

“You know,” she began again, “I never knew my father.”

“You never met him?” I asked, steadying my hands around my tea, grown cold in its thin china cup.

“I knew his name,” she said, with a long intake of breath, her gaze on the cake rather than me. I could see the effort it took for her to utter these simple sentences, perhaps for the first time in forty, fifty years.

“Herb Reissman.” She paused, her brow drawing in on itself, and looked up from the cake and into my eyes. “I saw him. Once or twice. Maybe three times. He came to Gloversville to see me. He came—” she paused and I saw both the relief and the anguish in her pale amber eyes—“not to our house because my uncles would have killed him. He abandoned my mother, you know. They would have strung him limb from limb. But he came to the restaurant and sat at the counter, and just looked at me.”

“You never talked to him?” I asked, nervously, ready for her guard to shoot up, for her anger to rise.

“It’s a funny thing,” she said, smiling into her own cup of tea. “I don’t remember.” She looked up at me again, in a manner that reminded me of my children, when they woke in the night, disoriented by the darkness. “How can I not remember?” she asked. I shook my head, in sympathy. “But I don’t. I never have. All I know is he came to the restaurant and looked at me. He wanted to see me. I don’t know how I knew he was my father. I don’t know if he told me, or someone else told me—” her voice broke and as I watched her eyes fill, I noticed my tears forming in my own—“I don’t know, Joanna, I don’t know. All I know is he wanted to see me.”

We sat at the table, covered in an oil cloth imprinted with pale blue flowers, until dusk fell. The big Victorian, my mother dancing through it in frilled dresses, had been a quadplex, filled beyond capacity with her aunts and uncles and cousins. She’d worn, for her whole childhood, her older cousin’s hand-me-downs, which hung wrongly on her spindly frame. And my father’s parents—those Lower East Side labor activists—had regarded her with derision, not good enough for their family of respected intellectuals.

“They thought I was some hick from upstate,” she said, coldly, as if the injury were still fresh. Perhaps it was. “But your father didn’t care.” She sighed, her eyes again filling with tears. “I was the love of his life.”

“And he was yours?” I asked, smiling, my father’s daughter, always trying to lighten the mood, to ease the pain.

“Maybe,” she said, with a shrug. “If you believe in that kind of thing.” She looked at me, hard. “I guess you do. You’re a romantic. Like your father. He always saw himself as a romantic hero.” Her voice had taken on a sardonic edge and I suddenly felt afraid, as I had two decades ago in the car with my father. Something would be revealed, something I didn’t want to hear, didn’t want to know. “He needed to see everything a certain way. Glamorous. Special.”

I nodded, strenuously attempting to appear calm, as the scales fell from my eyes. All those years, a lifetime, I’d believed the stories, the mythology, the Storybook Childhood had been put in place by my father to protect my mother. The silence, the omission, the reinvention.

But it had been the opposite all along.

My father had reinvented the world to adhere to his vision, his dream, his ideas of himself. My mother had merely played along. The stories, she knew, had ensured his survival.

Just as they ensured mine.

***

Not long after our conversation, I left the Lower East Side. In a new city, my older kids and I made a new life, a happy life, and the person I’d been—the person in thrall to my father’s mythology—slipped off me, like a once-loved dress now reduced to tatters. When my third child arrived, I felt a twinge of panic, that she was not, would never be a native New Yorker, that the streets I walked with my father and my son—still the streets I know better than anywhere in the world—would remain foreign to her. But soon, a sense of peace set in: She was free. In a way I had never been.

Last year, my mother died. In her final days, I held her warm hand, reminding her of our favorite escapades from my childhood, unvarnished, as they happened, or at least as I remembered them. My kids, all three, came down to New York with me for the funeral and we visited my old neighborhood together, walking the streets I’d walked with my father, and then my son. Across Delancey and up Orchard and east on Grand, the salty brine of the pickle barrels filling the air.

What stories did I invoke, I wondered, as we walked and walked those streets—my father a silent presence at my side—reminiscing about our years on those blocks. I strove, at every turn, for honesty over mythology, for answers rather than silence. But perhaps—it occurred to me as the wind from Corlears Hook burned my eyes—my father had done the same. Perhaps we are all at the mercy of our helpless selves. What stories did I tell—was I telling them at that very moment—in order to survive, and what stories did I invent to make it through my days? What stories did I omit? Has silence allowed me to survive, too? And can they, will they, forgive me?

Thanks for that very personal history lesson, Joanna. When my mom died, the crematorium asked my brother if he’d like to have a genetic analysis done on her remains. He said “sure.” A few weeks later the results came back: She was one quarter Ashkenazi. So three generations back, one of my maternal great grandparents was likely Jewish, probably fleeing some kind of hell and settling in Germany (!) with an invented identity. And after a lifetime imagining myself as WASPy as they come, I realized that I’m 1/16th Jewish. The secret persisted until DNA analysis exposed it. Secrecy is a rotten foundation for a family. Personally I think that makes my background more interesting, but I have the luxury to be a little bit Jewish and not die because of it.

Beautiful story. For some reason, I keep replaying a therapy session my mother agreed to go to with me and my sister, in which she said, "I don't know why you girls want to keep bringing up the past. Can't we focus on the future?" Her past was the devastating loss of two of her four children, and my sister and I's past was the devastating silence around the loss of our siblings. And then I wonder what my kids will want to go to therapy about. What am I not talking about that's harming them?