(Contains spoilers for the Black Mirror episode Eulogy.)

“Nothing sounds as good as…I remember that.” - Prefab Sprout, 1988

Having grown-up watching reruns of Twilight Zone when I was a Harlem kid in the 1970s, decades later I still love weirdo anthology programming.

Since 2011, the Netflix series Black Mirror has been my must-watch-immediately show. Created and written by Brit scribe Charlie Brooker, many of the episodes deal with technology gone wrong scenarios that usually have sad (or tragic) endings. Though I’m a fan, no episode has ever touched the sentimentalist in me the way a few of The Twilight Zone’s had, especially the one when the world has been nuked and the protagonist just wants to read, but he has accidentally broken his glasses. “Time Enough at Last,” written by Rod Sterling and starring Burgess Meredith as the saddest bookworm in the world, was heartbreaking to watch when I was a boy, and decades later still leaves me weepy.

However, Black Mirror finally took me there with an installment in the latest season. “Eulogy”—led by the world’s favorite curmudgeon, Paul Giamatti, as a lonely man named Phillip—opens with Phillip receiving a phone call from a company called Eulogy telling him that his long ago ex-friend Carol has died. The caller explains that a company called Eulogy is preparing “an immersive memorial” for Carol’s funeral and asks if he can “contribute a memory” that would “mean so much to the family.” Soon afterwards, the caller offers to send a kit.

When the box arrives, inside is a booklet and a small chip that serves as a commutation device between him and a woman who had introduced herself as “The Guide.” Sitting in his home office, where there are shelves of albums and a fancy stereo in the background, Phillip pretends that he barely knew Carol, but the depth of their relationship is slowly revealed when The Guide informs him that he can trigger memories from old photographs. Retreating to the attic where there are pictures stored in a vintage Converse sneaker box, he locates three snapshots that serve as the beginning of his journey to back to yesteryear.

In the first pic, snapped at a party on the roof of their Brooklyn squat, Carol’s back is turned and Phillip can’t remember what she looked like. It is then that The Guide, an artificial intelligence bot played by Patsy Ferran, informs Phillip that she has the capacity to put the two of them together, literally, inside the image. All he has to do is connect the chip to his temple. For the remainder of the episode, after Phillip confesses that he and Carol were a couple for three years, he and The Guide examine the bliss and sorrow of the relationship.

Unfortunately Phillip had erased Carol from his consciousness and so in every picture he has her face burnt out from a cigarette, scrawled away with a black marker, or cut out. Still, with The Guide leading him, together they attempt to conjure not just Carol’s face, but also their time as a couple and what really happened. “We were together for three years and it took fifteen to get over her,” he screams, believing the breakup was completely her fault.

Thankfully, through photos, postcards and music (Carol played cello beautifully, but was also a Stone Roses fan) Phillip begins getting closer to the truth. Though he is obviously afraid of where revisiting those images and sounds might lead, he takes the chance.

Watching that episode I thought about my process as an essayist, and how much I’ve used photographs to recall my past: my years as a New York City boy; spending numerous Julys in Pittsburgh with my “summer mother” Aunt Ricky; going to Daddy’s place on the weekends; spending time with my godfather Uncle Hans on the living room couch as grandma prepared southern delights in the kitchen. Without a doubt, my mother’s extensive photo album archive has been blessing, a resource that has helped enrich my texts considerably.

I asked why she had so many pictures, some going back to the late-1950s and early-‘60s (I was born in 1963), and she told me that my grandma didn’t have any pictures of her girlhood or early teen days in New York City, and she vowed as an older adolescent, when she got her first Brownie camera, to document the people and landscapes around her.

Before digital cameras were on every phone, even casual picture-taking took effort that involved buying film and flashes. When the pictures were taken, mom dropped the rolls of film off at a local drugstore that sent them out to be developed. After getting the photos back, she’d write on the back the year and who was in the images. Today, at 87, she still has a rather good memory, and there are afternoons when we’ll flip through a random album as she tells me details of the lives of various friends and family, many of whom I know only from viewing their faces through thin photo album plastic.

In 2008, having already started writing personal essays mixed with cultural observations for my blog “Blackadelic Pop,” I wanted to write about my Grandma, Mary Peterson. After co-raising me through childhood, she had passed away in 1994, but fourteen years later I kept thinking about her standing over a stove making chitlins for me instead of resting on her cancer deathbed.

Watching the “Eulogy” episode of Black Mirror, I thought about my process as an essayist, and how much I’ve used photographs to recall my past: my years as a New York City boy; spending numerous Julys in Pittsburgh with my “summer mother” Aunt Ricky; going to Daddy’s place on the weekends; spending time with my godfather Uncle Hans on the living room couch as grandma prepared southern delights in the kitchen. Without a doubt, my mother’s extensive photo album archive has been blessing, a resource that has helped enrich my texts considerably.

Living in Brooklyn years later, I asked mom to send me a few pictures of grandma, two of which I used in the Southernist essay, “Filth from the Swine,” that I published in October, 2008 The last twenty years of her life had been a rather bleak time with the death of her boyfriend Joe and many other dark days, but in one of the pictures she is laughing, and in the other it looks as though she is being a hostess, something she did very well and loved doing. Those black and white pictures reminded me of the cheerful, but nervous Mary Peterson of my childhood: the woman who picked us up from the babysitter, cooked most of the meals, and every Friday night asked me, “Michael, what channel does Sanford & Son come on?”

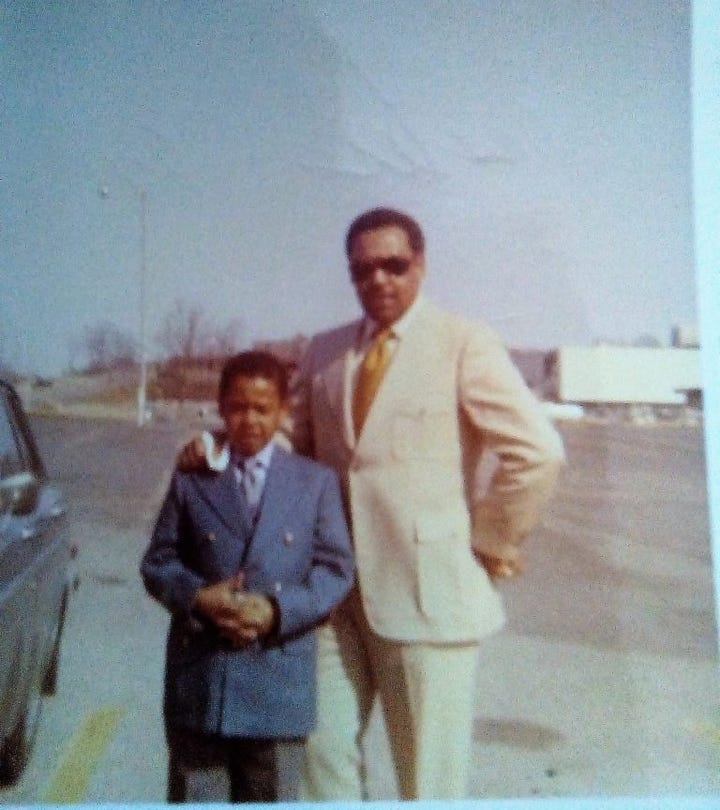

One year when I was 10 and my brother Perky was 8, mom gifted us cameras. They were boxy Kodak Instamatics, and we took them outside on special occasions, including Easter, 1974. My biological father, Lafayette Dixon took us somewhere I can’t recognize from the picture that Perky took of me and him. It’s actually one of the few we took together, ever. Decades later when I was writing about Lafayette for the CrimeReads essay “A New York State of Mind: The Unexpected Bonding Powers of Billy Joel's Melancholy Noir,” I located that picture of him in a beige suit and sunglasses, and it was as if I’d entered a time machine.

When I started writing essays I used mom’s archives, but I also relied on images online. Having grown-up on 151st Street between Broadway and Riverside in Manhattan, I hit the jackpot when I discovered the work of Thaddeus Wilkerson, an early 20th century photographer who took hundreds of pictures of my old neighborhood, which I’d found on the Museum of the City of New York website. Wilkerson had lived on 145th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam directly across the street from P.S. 186, where I attended to 1st grade. Moving steadily up Broadway (and Riverside Drive), from 1910 to 1916 he took pictures of buildings, side streets and parks, some that were made into postcards. Though the demographics of the community changed over the years, the apartment houses, schools and landscape remained the same.

There are other contemporary photographers whose books, prints or online images I often scan when in need of inspiration including: Gordon Parks, James Van Der Zee, Martha Cooper, Ernie Paniccioli, Joe Conzo, Jamel Shabazz, and Dawoud Bey—especially a postcard photo I got of a cool kid chilling in front of the Loew’s Victoria movie theater on 125th Street, from the Studio Museum of Harlem. That picture was snapped down the block from the hospital where I was born, around the corner from my stepfather’s crib, and a short walk from Rice High, which I attended from 1977 to 1978.

Another photographer I admire and have worked with is Newark, New Jersey-based Akintola Hanif, publisher and editor-in-chief of the photo journal HYCIDE founded in 2011. With then-New York Times writer Fayemi Shakur serving as editor, my first HYCIDE essay was “Black Hiroshima.” I was sent a stack of Hanif’s pictures of crack addicts and asked to textually riff from them.

In addition I’ve been good friends for years with two wonderful Lower East Side-based photographers, Alice Arnold and Maggie Wrigley, both of whom I’ve worked with on stories and art projects. And as with mom’s archive, both have many photos taken of me throughout the 1990s. In 2024 when I wanted to write a memorial essay about the life and death of my girlfriend Lesley Pitts, it was Alice who supplied me with the photos that served as my guide.

The same week I watched that Black Mirror episode mentioned above, I chanced upon a wonderful feature on the Evergreen Review site called “My Orphans: Snapshot Stories of An Analog World” by Jane Ursula Harris. In the piece’s prologue, Harris writes about buying random photos from Brooklyn junk shops and using them as inspiration for “snapshot stories,” flash fictions based on those images. “As someone who grew up in a family that hardly ever took photos and kept no family albums, I was compelled by the stories they at once held and withheld,” Harris writes. “There was so much beyond the personal too; these were cultural artifacts, enticing material objects that carried in them the many histories of New York, and that of photography itself.”

***

In the new millennium one of the best inventions has been YouTube, another of my go to sites when writing essays. After I know exactly what I’m going to write about and what years, I go to YouTube to watch movie trailers, bits of TV shows and commercials. I must’ve watched over a hundred television ads from the 1970s when I was writing yet story about my grandmother, “Queen of the Supermarket.” Documenting granny’s excessive shopping in NYC and New Jersey, those commercials of long discontinued products featuring long forgotten spokespeople or animated mascots, informed the piece greatly.

In Eulogy, when Phillip and The Guide enter a photograph taken at another party, she sees a cover for the Stone Roses single “Fools Gold,” and tells him, “Music’s great for jogging the memory.” Seconds later, when the song starts playing, Phillip loosens up as the memory comes alive, and he smiles. Many of us have had the experience of being in a store when a song we haven’t heard since childhood comes on through the overhead speakers, pushing out classic pop songs, and you remember every lyric. Which is why every time Guns‘N Roses’ “Welcome to the Jungle” plays, I remember my first trip to Los Angeles; I think about my mid-1980s girlfriend Initia whenever Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” is on and I reminisce about working at Tower Records when I hear Bryan Ferry singing. When I fall down a soul stereo rabbit hole of Prince and Aretha Franklin, I see images in my mind of Lesley and recall our life together in our first-floor Chelsea apartment from 1992 to 1999.

Music was weaved throughout the Eulogy episode, including by The Head, a band Phillip and Carol played in, as well as her own original avant-garde composition played on her beloved cello. Earlier we see a photo of young Phillip looking lovingly into Carol’s room as she practices, but it isn’t until the very end of the segment, after he locates a cassette of the song in his desk, plays it as he reenters the picture and stands behind his mid-20s self, that he’s finally able to see her radiant, smiling face. Letting go of the pain of distorted truths, Phillip finally exhales.

At 58, as a fairly new memoirist, I've realized that I functioned in my family as the archivist--looking at photos, asking questions, listening to my mother's and grandmother's stories about Peru, taking photos and videos as an adult, remembering and recording and remembering again. I've used photos as launching points for a few of my memoir-essays, as well as music from my youth--from Pachelbel's Canon to Prince's When Does Cry. Of course the master of the sensory memory trigger is Proust and his famous bite of madeline dipped in tea. Thank you for writing about your process and including those amazing photographs.

Wonderful! I loved reading this and the tip about YouTube for commercials is golden. Thank you.