It's Not Over Until the Bride's Father Sings

Introducing "Goodbye to All That" — a new Memoir Land vertical — with a story about eloping to the old, no-frills Manhattan Marriage Bureau.

Readers, today, on my 19th anniversary of eloping to the Manhattan Municipal Building, I’m launching a new vertical of Memoir Land called “Goodbye to All That”—named for the first of my two bestselling NYC books.

Despite having edited two anthologies with 58 New York City stories combined, I realize I’m not anywhere near done with the subject. I’ve been itching to share more of my own New York stories, — and to publish those of others — about living in the world’s most wonderful, terrible, astonishing, perplexing, inspiring, exasperating, metropolis, a place where I sometimes felt eager to spend every remaining day of my waking life, and other times felt doomed never to be able to leave.

The stories in this section are meant to evoke those dichotomies, and the constant push-pull New York City exerts on its inhabitants, making it equally difficult to leave and to stay.

I don’t yet know with what frequency I’ll publish in this vertical. I’ll probably publish on Wednesdays, alternating with First Person Singular essays. For now I am not accepting submissions. I have some things to figure out. Stay tuned for more about this down the line…

It's Not Over Until the Bride's Father Sings

I couldn’t have found a more effective way to break my father’s heart. I eloped to City Hall—a dingy room in the Manhattan Municipal Building, to be specific.

Other parents grieve when their children run off, even when it’s their daughter’s second time down the aisle and she’s 39, as I was. But my father is Mr. Wedding, a well-known cantor to whom just about every Reform Jewish girl in New York will happily shell out top dollar for singing at her nuptials. Twisting the knife, my fiancé, Brian, was Catholic.

My father gives good wedding, complete with soulful chanting in his Metropolitan Opera award-winning baritone and thoughtful comments about each couple. I can hardly say my last name anywhere in Manhattan without hearing someone gush about the wonderful wedding he performed for a daughter.

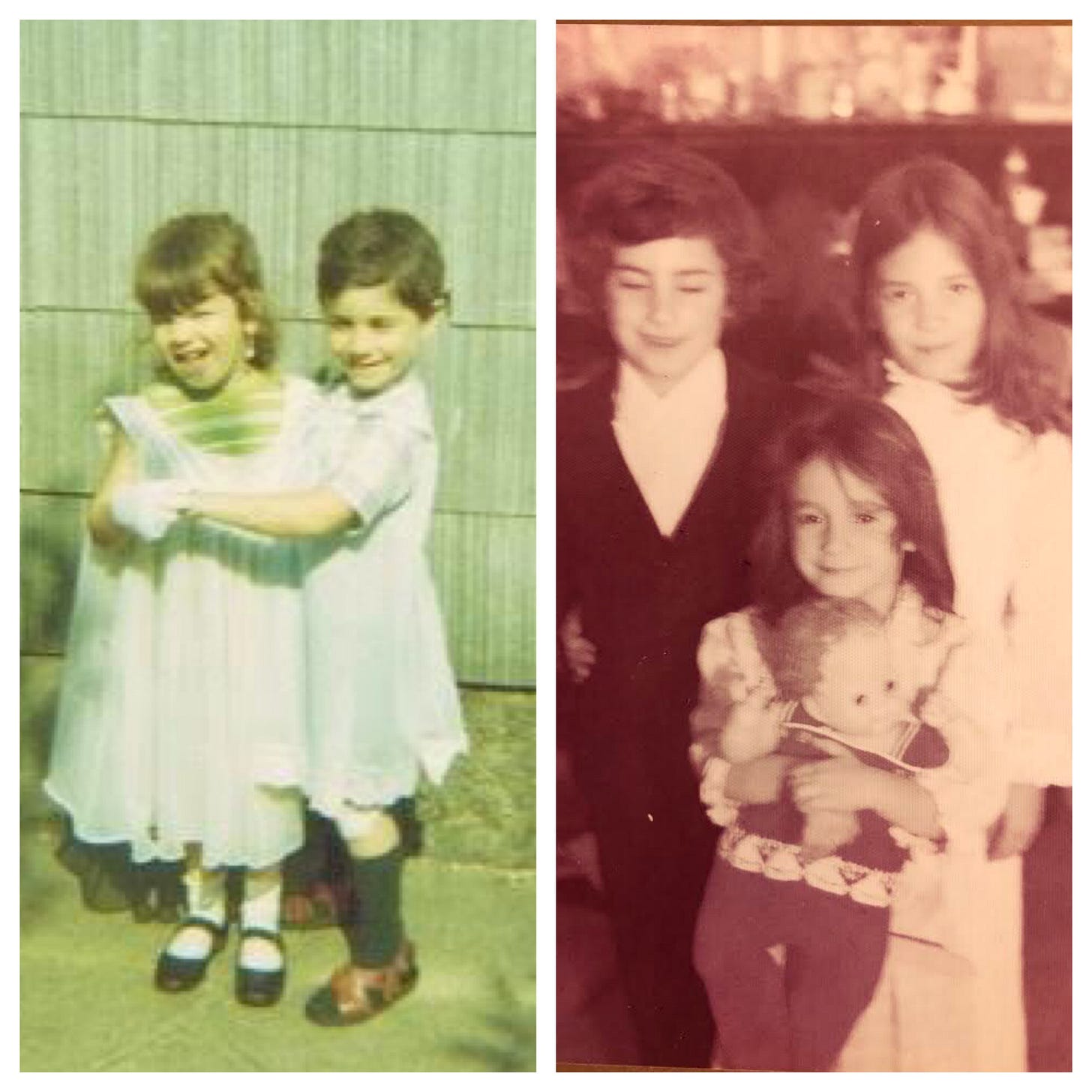

I grew up going to weddings. After my parents divorced when I was 10, my father used to pick up my sister and me for visitation after Sunday school. Often, our first stop before the movies would be a wedding ceremony he was performing. These events always gave me a little thrill. I, a child whose father had just moved out, was fixated on matrimony. I’d already wed my gay neighbor twice, when we were 3 and then 6 (we both wore gowns). I couldn’t wait to do the real thing.

In too big a hurry, I married my college sweetheart, in a ceremony performed by my father in a temple, when I was a clueless 23. We split when I was 26. After the divorce, I took my time—thirteen years—getting to my second wedding, the one that tore my father apart.

Upsetting him was never the point. My fiancé and I had a practical reason for going to City Hall on a blustery February afternoon in 2005. We were getting kicked out of our East Village apartment and needed to earmark our wedding money for a down payment on a new place. I had also harbored a secret desire to elope. Since I’d already had the Big Jewish Wedding the first time around and had attended so many similar affairs in the city, that custom had come to feel hollow. I wanted to live out a different New York fantasy.

Other parents grieve when their children run off, even when it’s their daughter’s second time down the aisle and she’s 39, as I was. But my father is Mr. Wedding, a well-known cantor to whom just about every Reform Jewish girl in New York will happily shell out top dollar for singing at her nuptials. Twisting the knife, my fiancé, Brian, was Catholic.

The biggest factor in our decision, though, was religion, or our common lack thereof. Brian was nonpracticing, and I hadn’t been to temple in years. The divisiveness organized religion could cause had troubled me for years, ever since 1976, when I was 11 and got my first boyfriend, a non-Jew. We were “going out” in the sixth-grade sense of the term, which meant that we never really went out except to walk together to a pizza place near school at lunchtime on Fridays. If the relationship could have led to something more, I’ll never know, because at my father’s urging I broke up with him after two weeks.

“You must end this!” my father pleaded, a divorced, disco-era Tevye with a Jew-fro and a shiny Huckapoo shirt. “I counsel couples all the time, so I know it rarely works with two religions.”

“I’m 11,” I reminded him.

“But dating is premarital behavior!”

That was the end of that.

When I was 15, on the way home from confirmation class at my father’s Manhattan synagogue, I casually informed him, “By the way, I’m not Jewish anymore.” I’d learned that afternoon that David Ben-Gurion, the first Israeli prime minister, once said that to become a Jew, all you had to do was decide you were one. I figured it had to work in reverse, too.

This was not random rebellion. My declaration was coming from a much deeper place: the boy my father had made me break up with in sixth grade had now made the high school football team. He was suddenly very popular, and he hadn’t spoken to me in the four years since I’d broken up with him.

My father was relieved when, in my junior year in high school, I picked a boyfriend who was a member of the tribe. My next boyfriend, in college, was also Jewish, and he became husband No. 1. But that was the end of Jewish boyfriends for a while.

I loved our no-frills civil ceremony at the Municipal Building, in an institutional room with bad fluorescent lighting. It was intimate and private, and we got to focus on each other without worrying about whose heritage was better represented, or who would be seated on the dais. Afterward, we walked to the middle of the Brooklyn Bridge for a Champagne toast.

Now and then my father would try to intervene. Once, he set me up with the fellow who stayed late after Friday night services to rearrange the prayer books. My father also campaigned endlessly for the television “gadget guru” I’d met at a trade show. When that guy got busted for selling cocaine, I sent my dad the Associated Press article by e-mail. Subject line: “Your son-in-law, the gadget guru.”

When Brian and I announced our engagement, my father thankfully spared us the lecture about the challenges of a mixed marriage. He even offered to perform our wedding. But we wanted a ceremony that fit us uniquely—a “recovering Catholic” and a wayward Jew, both with Buddhist leanings. We wanted to make everyone happy, not just my parents, but also Brian’s mother, an orphan who was raised in convents. We decided to just go to City Hall and have a party later that year.

I loved our no-frills civil ceremony at the Municipal Building, in an institutional room with bad fluorescent lighting. It was intimate and private, and we got to focus on each other without worrying about whose heritage was better represented, or who would be seated on the dais. Afterward, we walked to the middle of the Brooklyn Bridge for a Champagne toast. I can’t think of a happier moment. Before escaping to the Catskills for a honeymoon weekend, we made a quick round of calls.

“Well, if there’s anything I’m not,” my father said slowly on the other end, “it’s unhappy for you.” His usually confident voice was unsteady, barely masking his disappointment. My throat grew a lump. A few months later, we argued over who was more neglectful of whom. My father won. “You ran off and got married without your parents present!” he yelled. “By a civil servant! A nobody!”

I thought I could make it up to him at the small celebration we’d planned for a few months later. Brian and I had discussed a “some from Column A, some from Column B ceremony,” with a little Thich Nhat Han here, a little Rumi there. I could give my father something to do—a kiddush, maybe.

Then we went to a friend’s Park Avenue wedding. Brian eyed the chuppah as we sat down. “It symbolizes the couple’s first home,” I whispered. “Oh,” he whispered back. “Can we have that?” Next, he heard the cantor sing sheva bruchas, the seven blessings meant to send the couple off to a life of health and happiness. Brian leaned in again. “Can we have that, too?”

I couldn’t very well have a chuppah and sheva bruchas without enlisting my dad to officiate. It felt surprisingly good to ask him. He didn’t even try to hide his glee.

On a hot Sunday in June of 2005, under a homemade chuppah, my mother and Brian’s mother lighted a unity candle together. His brother and nephews took turns reciting lines from a traditional Irish blessing. Then my father did what the other New York Jewish girls pay him the big bucks for: he offered many kind words, and sang one blessing after another, magnificently.

Funny and touching. I particularly liked “a divorced, disco-era Tevye with a Jew-fro and a shiny Huckapoo shirt.”

Beautiful. Just beautiful.