The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #64: Seth Lorinczi

"'Death Trip' asks, 'Can trauma be inherited,' and, if so, 'Can psychedelics help us heal?'"

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

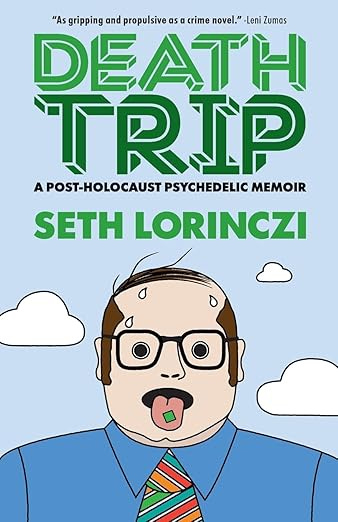

Here’s the 64th installment, featuring , author of Death Trip: A Post-Holocaust Psychedelic Memoir . -Sari Botton

Seth Lorinczi’s writing appears in The Guardian, DoubleBlind, Narratively, Portland Monthly and other print anthologies and periodicals. In addition, he was a co-founder of “Judaism & The Psychedelic Renaissance,” a first-of-its-kind live event in Portland, OR.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I’m nearly 54; I’ve been writing—with one major break—since 1996, when I was 25.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Death Trip: A Post-Holocaust Psychedelic Memoir was published in May, 2024.

What number book is this for you?

This is my first book!

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

When I began drafting, I was taken by the idea of the “nonfiction novel”—though that term has kind of disappeared, if it was ever really a thing. The reason was that I wanted to deemphasize the memoir aspects and play on the historical ones instead. But again and again, my writing partners pushed me to focus more on my story rather than the historical or journalistic parts. I think they recognized the book was memoir long before I did.

As my personal life fell apart I stumbled upon my father’s memoirs—20 pages, give or take—and realized I had a backstory, maybe even an interesting one. (My father’s family were Hungarian Jews who’d barely survived the Holocaust and the Battle of Budapest.) Using my father’s recollections as a roadmap, I began to write about them.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

A marriage story, a search for meaning in the wake of the Holocaust, and a struggle to release the weight of ancestral trauma, Death Trip is a memoir about self-acceptance, forgiveness, and redemption. Along the way, it takes readers from the ayahuasca basements of Portland's psychedelic therapy underground to the streets and alleyways of Budapest during the darkest days of World War II. By turns wrenching and hilarious, it asks, "Can trauma be inherited," and, if so, "Can psychedelics help us heal?”

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I never intended to be a writer! In the mid-90s, I was halfway through cooking school before I finally faced the fact that I wasn’t cut out for restaurant work. Then a writer and food stylist from the SF Chronicle delivered a guest lecture, and I realized I could write about food instead of making it. I had a brief career as a restaurant critic—best job I ever quit!—and then pursued my first love, music, for the next 15 or so years.

When music fizzled out, I was at a crossroads—personally and professionally. Desperate for work, I turned towards copywriting and made some headway. More importantly, as my personal life fell apart I stumbled upon my father’s memoirs—20 pages, give or take—and realized I had a backstory, maybe even an interesting one. (My father’s family were Hungarian Jews who’d barely survived the Holocaust and the Battle of Budapest.) Using my father’s recollections as a roadmap, I began to write about them.

But in the 20 years since my father had died, I realized there was a great deal he was obscuring—or wasn’t saying at all. The people who raised me suffered fairly intense trauma, and—helped greatly by psychedelic therapy—I began to recognize that their experiences might be guiding and distorting my own perspective of the world. So I began to dig deeper. Eventually, I recognized I’d have to go to Budapest to try and find the parts my father had left out of the story. Let’s just say I got far more than I asked for. Hence the book.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

This is a raw and vulnerable book, and many people who know me find it tough going. But I had the strong sense that if I really wanted to change my life, I’d need to delve into the most challenging aspects—the trauma my ancestors suffered, how it shaped me, and the ways it was affecting how I showed up as a husband and a father.

But the real crucible was trying to get it published. I wanted the stamp of approval—an agent, a publisher—but as I surveyed the landscape, it became clear that I stood very little chance of getting it published traditionally. When one of my writing partners pointed out that I’d grown up in the D.C. punk scene and already had the skills and orientation to go the DIY route, I decided that this challenge might actually be a portal.

So I co-founded a publishing collective and took it on. It’s hard work for sure, but the rewards have been truly great. I can’t count the number of times total strangers have been moved by the book and offered to help. At the moment a Hungarian imprint is considering translating and publishing the book, and I’m about to start production of an audiobook version—I couldn’t be more thrilled!

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

First of all, I read (and reread) Mary Karr’s advice on the topic. I shared relevant sections (or the entire manuscript) with the people affected, and made a few changes for the purposes of factual accuracy. But there were snags. Late in the revision process, I had a conflict—unrelated to the book—with someone who plays a major role in the story.

After they insisted they be removed, I had to do some serious soul-searching (and a deep dive into libel and privacy laws). Given the large volume of documentation and conversation I’d collected from them—giving me reasonable legal standing that I was portraying them truthfully—I opted to create a stand-in character so that their personal details would be unrecognizable (though I preserved their general role, observations, and dialogue).

I understand that’s not the “ideal” answer—it would read better if I said I’d simply honored their wishes. The fact is that I weighed my desire to be in connection with someone who I felt had been petty and vengeful, and I chose the book over the relationship.

There’s one other way in which identities were disguised. At the very end of my one-month trip to Budapest, a family member took me aside and explained that many of their friends weren’t aware they were Jewish, and asked if I could not mention this fact. I couldn’t, given the subject matter of the book, but with their consent I altered all my family’s identifying details. It’s painful to recognize that they felt this was necessary some 80 years after the end of the Holocaust, but that’s Hungary for you.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

So many! Close to home, Lidia Yuknavitch is an incredible resource and taught me a great deal about handling traumatic material with force but also with delicacy—imparting dense feeling states while often not even naming the trauma in question. And while my writing is nothing at all like his, Ross Gay’s Book of Delights was such a breath of inspiration and joy in quiet, ordinary-seeming moments.

I also read a lot about the Battle of Budapest—in my father’s words, the central event of my family story. The book that affected me most is pretty much unknown now—Nine Suitcases by Béla Zsolt—but it describes in very skillful and harrowing prose some of the experiences my father, grandfather, and extended family went through. It pushed me to get as granular as possible, and as much as possible try to place readers into these senseless and disorienting scenes themselves.

In the 20 years since my father had died, I realized there was a great deal he was obscuring—or wasn’t saying at all. The people who raised me suffered fairly intense trauma, and—helped greatly by psychedelic therapy—I began to recognize that their experiences might be guiding and distorting my own perspective of the world. So I began to dig deeper. Eventually, I recognized I’d have to go to Budapest to try and find the parts my father had left out of the story. Let’s just say I got far more than I asked for. Hence the book.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

Calling upon my experience in the punk scene transformed how I approached getting the book out into the world. I had a healthy distrust of gatekeepers and institutions before I found punk, but punk showed me how to do something with it. I recognized that going to my community for support and expertise would serve me far better than reaching out to more established “authorities.” Once I got over my desire for acknowledgement, it just became a matter of assembling resources and calling upon people in my orbit.

For example: because I had zero experience writing personal material, I really needed basic support in terms of craft. I asked the best writer I knew if they’d be willing to start a writing group with me; six and a half years later, we’re still going strong. And I reached out to local small presses—I bought a lot of people coffee!—and just asked them how they did it. In the process, I went from feeling desperate for a book deal to taking charge of the process and feeling my own sense of agency growing.

What do you love about writing?

Connection. I know that sounds counterintuitive because writing’s by nature such a solitary act. But the notes and other reflections I get back from the world are really heartening, and they make the material I write about—some of which is traumatic in nature—feel far less personal and far more universal. In other words, sharing my story takes the weight off me and seems to give others permission to share theirs as well. That feels like a big win.

What frustrates you about writing?

Finding an audience is hard. I often say: “I believe in reality.” Meaning: We live in the world we live in, and it’s up to us how we relate to it. That said, I recognize that my dreams of a writerly life are probably based on very outdated information. As outlined here on Substack by Christina Patterson and others, the opportunities for freelancers (and writers of all stripes) are vanishing at an alarming rate. I’m not great at Notes or other short-form posts that rely on the kind of “personability” which I lack—I’m speaking medically here, not self-critically. I wish there were more of a market for the kind of longform content I do, but at the end of the day it’s still up to me to find my audience.

What about writing surprises you?

I’m cerebral (and let’s face it: probably pretty self-absorbed) and it can be hard to drop into feeling rather than thinking. And so I live for those incandescent moments when something rises up out of the murky waters and I see a connection I couldn’t before. It’s a map of my past—and maybe my future—laid out before me. Once I find it, all I have to do is describe what I see.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

I used to write first thing in the morning—I try to be up before the sun—but these days I tend to my heart and my body first. A quiet sit, a run, walk the dog and then down to my studio. On writing days I’ll light a candle and burn a little sage or incense. I very much subscribe to the Elizabeth Gilbert notion of genius as something not native to individuals, but a spirit that visits when the invitation is made. Every once in a blue moon, it stops by for a moment.

I wanted the stamp of approval—an agent, a publisher—but as I surveyed the landscape, it became clear that I stood very little chance of getting it published traditionally. When one of my writing partners pointed out that I’d grown up in the D.C. punk scene and already had the skills and orientation to go the DIY route, I decided that this challenge might actually be a portal. So I co-founded a publishing collective and took it on.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

One of my writing partners once said: “A lot of writing happens when we’re not writing.” Meaning that resting the eyes and the brain is absolutely essential—not only for the work but for general life balance as well. I cook a lot, and in rare moments I restore old electronics—amplifiers, tape decks and such. It’s so diametrically opposed to writing—it’s more a handicraft, like needlepoint—and I feel it’s exercising some dormant part of my brain.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

I’ve been working—extremely slowly—on another memoir, this one about my time in the D.C. punk scene. I’d really hoped for it to be further along, but promoting “Death Trip” kind of turned into a full-time job—on top of my other job, which is being a copy writer. Funny, I’ve been hoping for a writing retreat the last year or so but not had any bandwidth. But on an upcoming (Feb. 2025) book tour, an organization I’m presenting with offered a one-week residency in the Hudson Valley. It felt like fate, so of course I said yes. I’m hoping to come out of it with at least an outline….

I purchased the book after reading for 30 seconds. My grandparents were Hungarian Holocaust survivors who lost siblings and loved ones and narrowly escaped, to Miami via Cuba. Then on to the midwest… My father was somewhat walled off emotionally, as this author describes, and the inherited trauma sounds so similar! My ancestors didn’t talk about their pain. Stories have been lost forever. So I will read this hoping to understand my own lineage better. Thank you!!

Hi, Sari. I've been wanting to thank you for some time for this series... I find it so helpful as I wrestle with my own doubts and questions about writing memoir! Every interview has something that speaks directly to me. And I find great resources, ie Lidia Yuknavitch.

Seth, thank you for sharing your process. I don't think it's wrong at all to choose your book over the relationship. The book has value and meaning and primacy too. I think about this as i prepare to share my manuscript with family members. They know I'm writing about our family history, but I don't think they recognize the emotional impact it will have to read it/see it in print.

That's part of why I'm writing it, to give voice to things long unsaid. Hopefully it will bring healing and peace. I love your reflection on how your book creates connection, taking some of the burden from you and allowing others to see themselves and heal. Best of luck to you!