The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #41: Marian Schembari

"I often feel as if I’m on the outside of things. Writing has always been my way to insert myself into the world."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

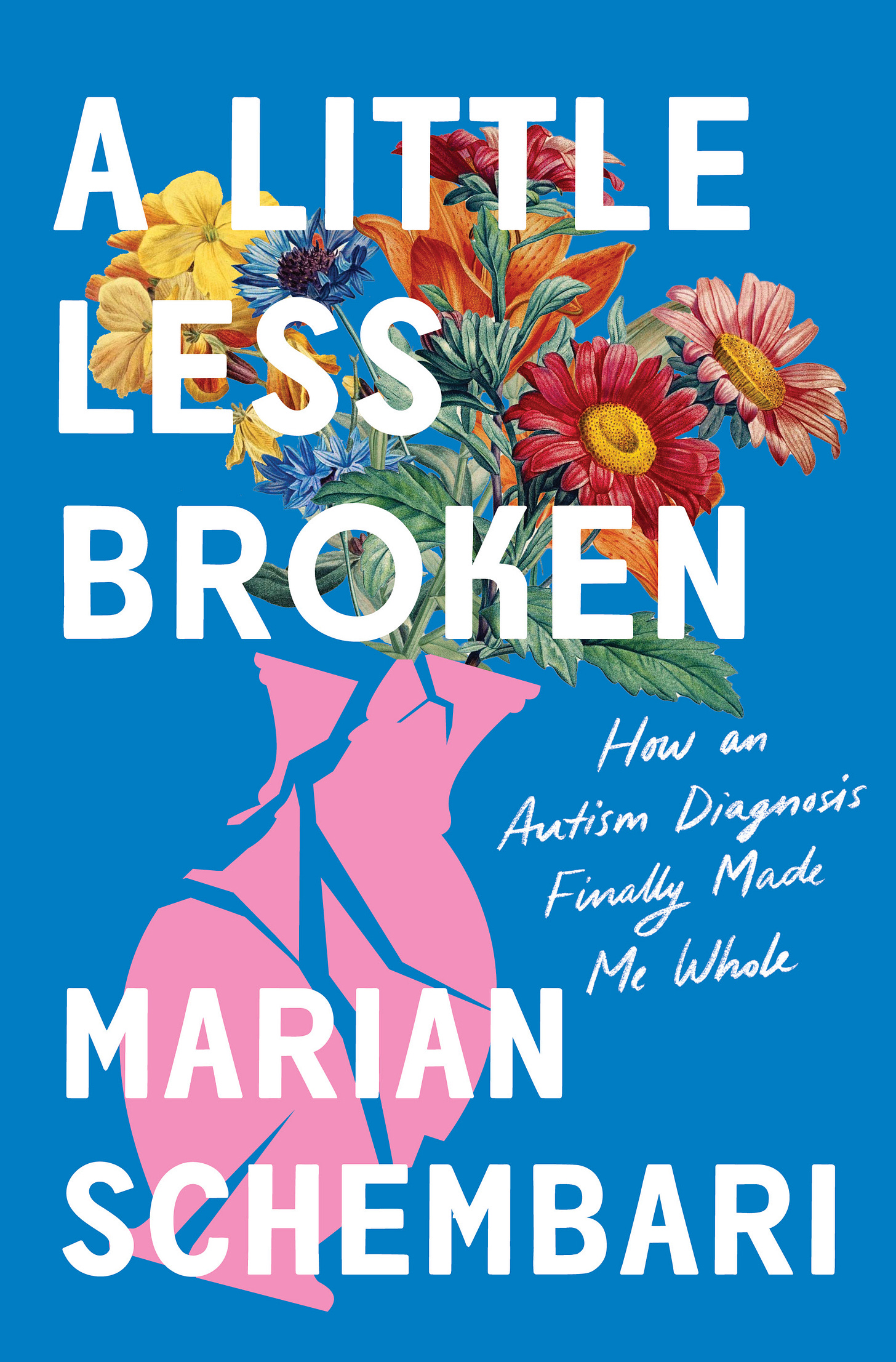

Here’s the 41st installment, featuring Marian Schembari, author of A Little Less Broken: How an Autism Diagnosis Finally Made Me Whole. -Sari Botton

Marian Schembari's first byline was at age 11 in Highlights for Children. It was a poem about dragons. Since then, Marian’s essays about travel, friendship, money, and love have appeared in the New York Times, Slate, Marie Claire, and Cup of Jo. At thirty-four years old, Marian was diagnosed with autism, which formed the basis of her memoir, A Little Less Broken. She lives in Portland, Oregon, with her husband and daughter.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I'm 37, and I've been writing pretty much that whole time. When I was 8, my journalist parents gave me a copy of A Writer’s Notebook by Ralph Fletcher, which encouraged young writers to record everything from their favorite words to snippets of conversation. I still have the notebook I started after reading Fletcher. Inside are conversations I overheard on the bus between two 8-year-old boys ("No, I'M THE BIGGER YANKEES FAN!"), my favorite words (wombat, crystal, edge), arguments with my third-grade teacher, lists of names I liked better than my own (Vicki! omg), and recaps of my afternoon walks through the neighborhood. I’d write descriptions of the most beautiful homes I passed, so I could later write stories about the happy families I imagined inside. I often feel as if I’m on the outside of things. Writing has always been my way to insert myself into the world.

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

A Little Less Broken: How an Autism Diagnosis Finally Made Me Whole. It was published by Flatiron Books on September 24th.

What number book is this for you?

First, baby!

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

It's a hybrid memoir, sometimes called a “reported memoir” or “memoir plus,” a form I only recently recognized as its own subgenre. Early on, it became clear that I couldn’t tell the story of my autism diagnosis without addressing a larger, more pressing question: Why are so many neurodivergent women missed as children? To answer that, I had to explore gendered medical bias and talk to other autistic people who didn’t learn they were autistic until later in life. While it’s mostly a chronological memoir that explores themes like identity, resilience, good therapists, terrible therapists, complex family relationships, parenting even though your mental health is in the toilet, trying to “meditate the pain away”—it’s also a cultural critique on why millions of women are continuously ignored, gaslit, and misdiagnosed.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

At 34, after spending decades hiding my tics and shutting down in public, wondering why I couldn’t just act like everyone else I finally learned the truth: I wasn’t weird or deficient or moody or sensitive or broken. I was autistic. My book takes you on a journey through the mountains of New Zealand to the tech offices of San Francisco, from my first love to my first child, to reveal what it truly means to embrace our differences. The book received early praise from New York Times bestselling authors like Temple Grandin, Susannah Cahalan, Amelia Nagoski and more. Kirkus called it "sparkly, humorous, and personable." Joanna Goddard said, "This book is a gift to humanity." (A gift to humanity! Tattoo that on my forehead! Whisper it to me as I fall asleep!)

Early on, it became clear that I couldn’t tell the story of my autism diagnosis without addressing a larger, more pressing question: Why are so many neurodivergent women missed as children? To answer that, I had to explore gendered medical bias and talk to other autistic people who didn’t learn they were autistic until later in life.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

I didn’t set out to write this book. My parents are both writers—my mom writes about airplane crashes (why yes, I am afraid of flying, thank you), and my dad’s been an editor at The New York Times since I was six. Naturally, I wanted to rebel and be a novelist, not a journalist.

I stopped and started a few novels—one about a witch, another about a bank robber, and one about my great-grandmother who ditched her kids. But none of them made it past the 25% mark. I loved the idea of writing, but honestly, finishing was hard, especially while juggling a kid and a full-time job as a copywriter.

By 2022, after years of telling myself, I’ll write a book someday, I wrote an essay about my recent autism diagnosis for the website Cup of Jo. The very next day, three literary agents reached out, all saying some version of, “You might already be represented, but if you’re open to talking book ideas, let’s chat.”

A few baffling conversations later, I signed with Mollie Glick at CAA. After a few conversations with her, it became clear that the autism story needed more space. Mollie asked for a book proposal ASAP, which I cranked out in three weeks. A few weeks later, my dream publisher made an offer that let me quit my job and focus on the book for the next two years.

Honestly, I still can’t believe it. In just two months, I went from "maybe someday I’ll write a novel about a misunderstood witch" to "I just sold a book about my misunderstood self that I haven’t even written."

That frantic, can’t-overthink-it energy really helped force me through my usual procrastination. Plus, it really really really helps when you’re getting paid to write, instead of working for years on something without knowing whether it’ll see the light of day. To dismiss the financial incentive here would be irresponsible. I’ve never been the type who can write on the same topic long-term without getting bored or distracted by something new and shiny. I need a deadline, a paycheck, something to keep me going.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

The hardest part of publishing is the constant feeling that everyone else knows something I don’t. Whether it’s about the industry or the act of writing itself, it feels like I’m stumbling through an unfamiliar bedroom in the dark. It’s cliché to say that publishing is a black box, but when you don’t know anyone in the industry, it’s tough. You want to come across as competent and professional, but you also don’t want to fuck yourself over by not asking questions or fighting for something you believe in.

For example, I hated the first cover design for my book and got so much conflicting advice on how to handle it. Some told me, “Trust the marketing team. You don’t want to develop a reputation as being difficult,” while others insisted, “Don’t settle for anything less than your perfect cover or you’ll hate looking at your own book.” (The best answer, of course, lay somewhere in the middle.) In my previous jobs, I always felt like I could rely on my talent, but in publishing, I often feel like I’m missing something crucial or making hideous faux pas that will ruin my career before it even really starts.

The one shining star in all of this has been my editor, Lee Oglesby, who is the kindest, most thoughtful, and talented editor on the planet. I got very very lucky, and couldn’t have done any of this without her.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

It’s funny—I stressed about this so much during the year I spent writing the book. It kept me up at night, I did a lot of therapy over it, read books on the subject, but in the end, it didn’t matter as much as I thought it would. Ultimately, the people who mattered didn’t ask for any changes and understood my perspective, even if it differed from their own.

Both my parents are journalists, and my dad had a popular family column for years while we were growing up. Our names—mine, my brother’s, my husband’s, and my daughter’s—are already public, so changing them for the book didn’t make sense. Plus, my parents used my name in print when I was a kid without my consent so I think they both understand that I can write whatever I want, even if there were moments in the book where I didn’t portray them in the most flattering light.

I sent the pages to six people and said, “If I got anything wrong, or misremembered something, please let me know.” I didn’t promise to change anything, but I did want to fact check my memories. There were a few instances where we remembered things differently, but no one asked me to remove or change anything.

I didn’t notify every single friend from childhood or the therapists and doctors from my twenties. To be perfectly honest, I didn’t feel like having Big Hard Conversations with people who are no longer part of my life.

While it’s mostly a chronological memoir that explores themes like identity, resilience, good therapists, terrible therapists, complex family relationships, parenting even though your mental health is in the toilet, trying to “meditate the pain away”—it’s also a cultural critique on why millions of women are continuously ignored, gaslit, and misdiagnosed.

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

I used three books as a sort of blueprint for how to write a hybrid memoir: Brain on Fire by Susannah Cahalan and What My Bones Know by Stephanie Foo. Both are “medical mysteries,” and I found their integrated use of research paired with deep vulnerability so gripping. The Honey Bus by Meredith May was another book I kept on my desk. While she might not describe it as a researched memoir, she uses bees and beekeeping as an overarching metaphor throughout the book. The way she pulls back to tell us about bees when she’s really talking about her absent mother is some of the most genius writing trickery I’ve ever seen. I was constantly inspired by her ability to craft a good sentence.

Finally, I have one inspiration tool that’s frankly a little unhinged, but I can’t imagine a world where I didn’t have access to it during the writing process: a Google Spreadsheet.

At the beginning of the writing process, when I panicked that I had no idea how to write a book and thought I’d have to give back my advance, I created a spreadsheet cataloging all my Kindle highlights that I’d been saving since 2010. So far, I’ve tackled 9,131 sentences, breaking them down into categories like Dialogue, Character Descriptions, Transitions, Summary, Sound, Taste, etc. (Tell me you’re autistic without telling me you’re autistic.) It’s my most-used writing tool—I rely on it for inspiration, education, and motivation when I’m not in the mood to write. It’s my most prized possession.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

I feel wholly unqualified to give advice because, honestly, I feel like I lucked into this. I didn’t spend a decade perfecting this book. I wrote the proposal in three weeks, sold it in two, and then wrote the whole thing in a year. It’s not the approach I would have chosen, because I worry it’s imperfect. But not having time to second guess myself was incredibly powerful.

For me, writing is a job like any other. When I ghostwrote or did copywriting for other people, I didn’t obsess over every word. I had a deadline, I wrote the thing, and I moved on. I’d like to treat my next project just like the first. That fast-and-dirty approach unlocked what I needed to finally fulfill my lifelong dream. It turns out I did have the ability to write and sell a book in a year. I can do it again.

So, my advice? Stop second-guessing everything. That’s advice to myself, too. Are you listening, Marian?

What do you love about writing?

I love the editing process. I can’t even think about trying to write a beautiful, true sentence until I have some sort of structure on the page. But once that structure is there? That’s where the magic happens. The drafting and structuring phase feels like I’m an architect, reverse engineering a good story, piecing together the frame. During the editing process (which takes me at least seven drafts to get right), that’s when I feel like an artist. It’s where I’m most creative, most free—playing with a single word for 15 minutes or trying on a thousand different ways to articulate the sound of the sea.

In my day-to-day life, my thoughts are always a jumble. I’m not particularly articulate in person. There are seventeen conversations going on in my head at any given time. My mind is never still. What I love about writing is the peace that comes with pulling out the exact thread of a thought. Without writing, I’m not sure I’d ever hear the sound of my own voice.

What frustrates you about writing?

What frustrates me is how little I know about what I’m writing while I’m in the middle of it. Every pass adds a new layer, and I know this with distance, but in the moment it’s so layered that it’s impossible to see the whole picture. The story just feels too big. I have to work at it one layer at a time, day after day, page after page. As someone who catalogs sentences for fun, this is deeply frustrating and, frankly, unpleasant. I hate this part, but I know I have to get through it in order to get to the fun stuff. What’s even more annoying is that I know this flailing is part of my process, but every time I start a new project, I’m surprised all over again by how adrift I feel, whether I’m writing a 900-word essay or an 85,000-word memoir.

What about writing surprises you?

I’m often surprised by the sentences I’m capable of writing. While most of my early drafts embarrass me, there are times when I’ll re-read a sentence months or years later and think, “Wow. I nailed that.” (With no memory of how it happened or how to make it happen again.) It’s like I blackout during the creative process, then come to later with a finished piece. It’s such a joy to see it all come together in the end. Every time I finish a piece, I’m amazed at how it all finally clicked.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine or writing at specific times?

Absolutely—my writing is the engine, but my routine is the fuel. If I don’t sit down by 8:30am, dressed, face washed, kid at school, breakfast eaten, with a fresh cup of coffee, then I’ve sabotaged myself for the day. Early doctor’s appointments, lunch dates, yoga class… if I do any of that first, stressful or not, I can never quite get into the creative groove. My brain just fades too quickly as the day progresses.

I’ve also recently started co-working with a friend, Shalene Gupta, who wrote the brilliant hybrid memoir, The Cycle. Three to four mornings a week, we hop on Zoom and write silently for an hour. When we’re done, we’ll sometimes talk about how it went, but most of the time it’s just the accountability to do what we call “touching the project.” Even if I only work on something for 15 minutes, just touching it gives my brain this momentum to keep it going, working in the background constantly.

The hardest part of publishing is the constant feeling that everyone else knows something I don’t. Whether it’s about the industry or the act of writing itself, it feels like I’m stumbling through an unfamiliar bedroom in the dark. It’s cliché to say that publishing is a black box, but when you don’t know anyone in the industry, it’s tough. You want to come across as competent and professional, but you also don’t want to fuck yourself over by not asking questions or fighting for something you believe in.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities do you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I’m obsessed with obsession. I always have a new creative hobby I’m puttering around with, but I don’t stick with it more than six months. It took me a long time to not feel ashamed of that “fickleness.” I took a yoga teacher training but never taught yoga. I took horseback riding lessons but never went faster than a trot. I taught myself to knit, made 12 sweaters in a season, then didn’t pick up my needles again. I’ve gone deep on backyard chicken keeping, rockhounding, piano playing, veggie gardening, Spanish speaking, friendship bracelets, singing…

I’d much rather have a patchwork of knowledge and experiences than a) none at all or b) one main interest. There’s just so much to be curious about, and I love the experience of getting absorbed into something new. And yes, many of these obsessions will inspire my writing.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

Writing books is all I’ve ever wanted to do, and now that I’ve done it, I don’t think I can go back. My next book is about abortion, and right now I’m trying to juggle the early stages of “How the hell do I tell this story?” while simultaneously launching and talking about A Little Less Broken. Easy! No pressure at all! Everything is fine!

Another late-diagnosed autistic writer here! 👋🏻 I relate so much to everything about this. I’m so glad more of us are sharing our stories with the world. Adding your book to my TBR!

So funny and heartening and warm-making to find yourself mirrored. Makes me feel less, well, wrong. Your book now top of my to-read list. Thank you Marion. And thank you Memoirland...