The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire #30: John DeVore

"In high school, I decided I wanted to be a playwright, and that aspiration made my dad moan. I told him my fallback career was acting."

Since 2010, in various publications, I’ve interviewed authors—mostly memoirists—about aspects of writing and publishing. Initially I did this for my own edification, as someone who was struggling to find the courage and support to write and publish my memoir. I’m still curious about other authors’ experiences, and I know many of you are, too. So, inspired by the popularity of The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire, I’ve launched The Memoir Land Author Questionnaire.

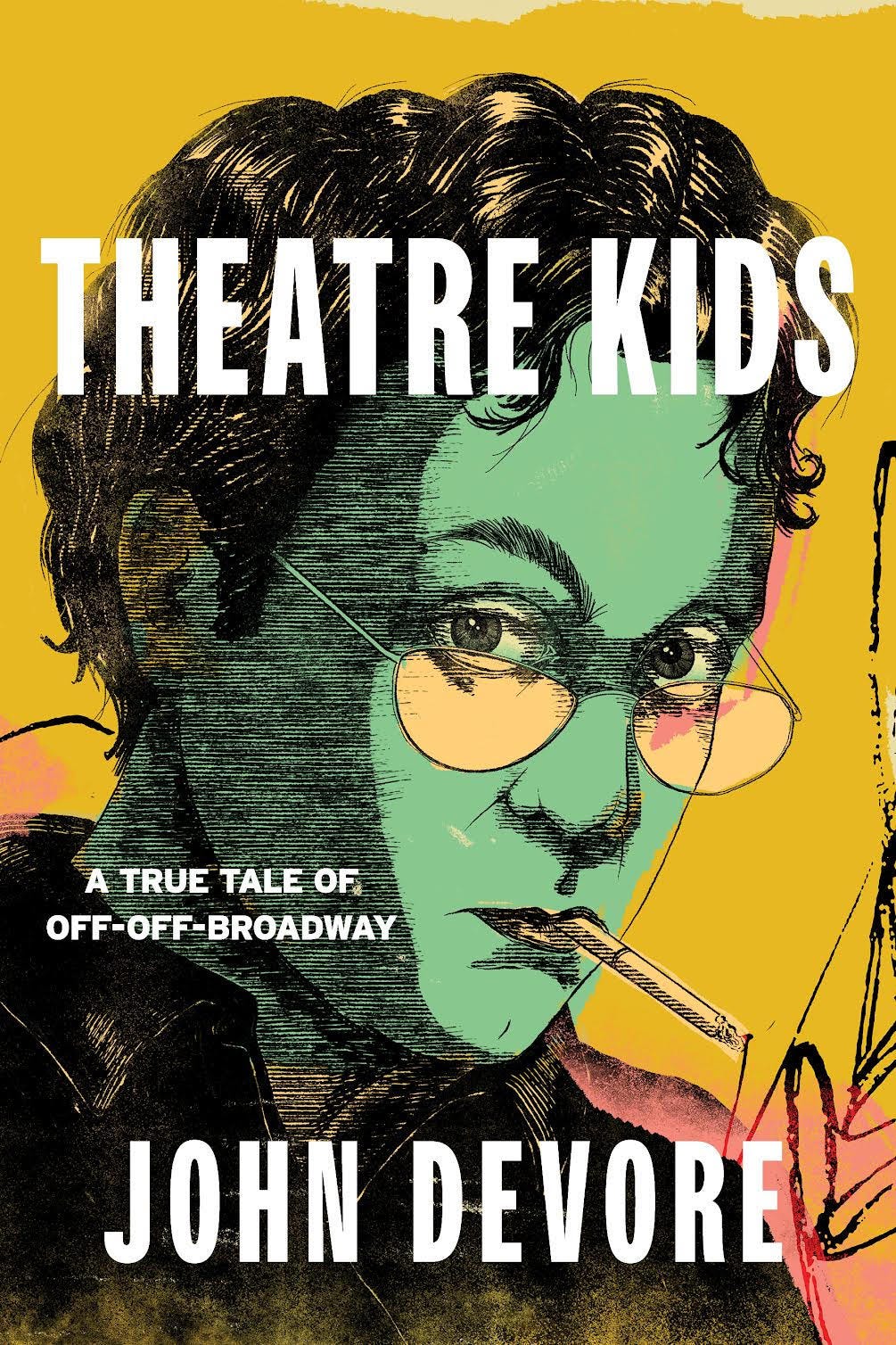

Here’s the thirtieth installment, featuring , author of Theatre Kids: A True Tale of Off-Off-Broadway. -Sari Botton

is a two-time James Beard Award-winning writer and editor whose essays have been published in Esquire, Vanity Fair, and Food & Wine, to name a few. John lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Ryan, and their ten-year-old, one-eyed mutt, Morley Safer. His debut memoir, Theatre Kids, was released earlier this summer.

—

How old are you, and for how long have you been writing?

I turned 50 years old a few days ago.

I've been a writer ever since 5th grade when Mrs. Crawford asked the class to write a short essay titled "What I Did For Christmas Vacation." In that essay, I wrote that the Grand Canyon looked as if it had been "carved by the Hand of God," a line I shamelessly stole from a short, overwrought promotional video I watched at the Grand Canyon visitors center, but Mrs. Crawford was so moved by that description that she told me I was a writer, and to my surprise, I agreed. Thanks, Mrs. Crawford!

What’s the title of your latest book, and when was it published?

Theatre Kids: A True Tale of Off-Off-Broadway. It was published in June, which feels like last year.

What number book is this for you?

This is my first book.

How do you categorize your book—as a memoir, memoir-in-essays, essay collection, creative nonfiction, graphic memoir, autofiction—and why?

Theatre Kids is a memoir that focuses on one specific time in my life—four months in 2004. I write a bit about the years leading up to this eventful season, but it mostly takes place during one winter twenty years ago.

What is the “elevator pitch” for your book?

Theatre Kids is a funny/sad memoir that I’ve described as Patti Smith's Just Kids meets Glee — or, if you prefer, Hipster Waiting For Guffman. It’s a very Gen X book about many things: addiction, masculinity, and suboptimal romantic choices. It’s also about making avant-garde art doomed to fail in post-9/11, pre-iPhone New York City.

The book tells the story of an experimental, four-hour adaptation of William Faulkner’s novel As I Lay Dying staged inside an enormous wooden coffin that could barely fit the eccentric cast, much less an audience, built inside a small, windowless theater in then-desolate Williamsburg, Brooklyn. It was a hopeless cause directed by a gently monomaniacal director. This production saved my life for a brief moment.

Theatre Kids is a funny/sad memoir that I’ve described as Patti Smith's Just Kids meets Glee — or, if you prefer, Hipster Waiting For Guffman. It’s a very Gen X book about many things: addiction, masculinity, and suboptimal romantic choices. It’s also about making avant-garde art doomed to fail in post-9/11, pre-iPhone New York City.

What’s the back story of this book including your origin story as a writer? How did you become a writer, and how did this book come to be?

In high school, I decided I wanted to be a playwright, and that aspiration made my dad moan. I told him my fallback career was acting.

I loved the very mid-century idea of the playwright — a serious, singular artist whose work could not be altered or edited at all. I dressed the part, too, and I wore thrift store tweed and long scarves. Instead of the Great American Novel, I wanted to write Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller's subversive masterpiece about the toxicity of capitalism, which is a hilarious ambition in hindsight. What was I thinking? I really had no idea how the world worked after graduating from theatre school, so I just assumed the want ads in the back of New York's free newspapers like the Village Voice would be full of employers looking for “playwrights.”

After a year or so as a temp, I would get promoted from receptionist to fact-checker at a small technology magazine. I learned journalism as a trade there; a half-dozen old-school editors gave me a very practical education in publishing. My first paid clip was a 75-word review of an ‘80s horror flick released on a new kind of physical media: the DVD. I was to review the technical specs of the format, not the artistic merits of the movie.

One thing that theatre school taught me was that any role was a good role. I had working actors as professors, and they really pressed upon me that booking a canned tuna fish commercial was as good a gig as getting cast as Hamlet. That is why writing about DVDs for magazines read by a few thousand people felt like the big time to me. I remember feeling very proud of putting down "writer" on my tax forms when I was 24. I shared that with my dad, who was also proud that I was paying my rent.

So Theatre Kids is the result of years and years of writing nonfiction proposals and tireless pitching from my agent, who believed in me. I’ve written short-form memoirs my entire life. I was part of the First Person Essay Industrial Complex of the late aughts and early teens. My goal was always to write a book and eventually, a friend of a friend mentioned she knew a book editor who was open to hearing non-traditional pitches about theatre, and so I got to work. I almost immediately had an idea for a memoir. The proposal poured out of me over the course of months and then we pitched him. He bought the book for a very modest sum. I’m still thrilled it ever happened.

What were the hardest aspects of writing this book and getting it published?

If you had asked me before writing this book, "How many drafts of Theatre Kids do you think you'll complete?" I may have replied, "Three? First, second, third?" Reader, if I could churn out another draft of my book right now, I would. It was, and still is, hard to let go of the book.

I have been telling friends that while I normally loathe comparisons to parenthood that don't directly refer to parenthood — for instance, my beloved dog is not my "baby," — I do feel that publishing a book is a little bit like having a kid. My book has a life of its own now. It exists in the world outside of me, and people are having relationships with it that have nothing to do with me. I cared for the book, and now it is free. That's hard but also amazing.

What was hard about getting it published? Literally, everything. There are rules, and then the rules change. There is self-doubt and setbacks, impossible highs and ice-cold lows. There are also weeks (months?) where absolutely nothing seems to happen. It’s work, but it’s worth it.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life? Did you use real or changed names and identifying details? Did you run passages or the whole book by people who appear in the narrative? Did you make changes they requested?

I once told an ex, “Lay down with writers, wake up with things written about you.” She thought it was mildly funny.

I did not change any names. The people I wrote about were friends and family who, during the months when the book takes place, loved me, which felt baffling at the time. They're heroes in the narrative because caring about difficult people, especially those in the throes of active addiction, requires a bit of courage.

I let most of the people I wrote about in the book read early drafts, and they all gave me feedback. Their suggestions made the manuscript stronger. One friend asked for a few factual changes, which I made because her memory of certain long-ago events was sharper. There is a difference between fact and truth, and a memoir is the truth after two scotches at an airport bar.

I did not extend this courtesy to my mom, however, who accepted long ago that I would be writing about her. She figures prominently in Theatre Kids. In 2014, I wrote an award-winning essay for Eater about Taco Bell and growing up with a Mexican-American mother. It was about our relationship and how challenging it can be to grow up with one foot in two separate identities. I didn’t ask her for permission then, either. My mom has always supported my writing, and to write what moves me, and she has lived to regret that in a way.

Instead of the Great American Novel, I wanted to write Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller's subversive masterpiece about the toxicity of capitalism, which is a hilarious ambition in hindsight. What was I thinking? I really had no idea how the world worked after graduating from theatre school, so I just assumed the want ads in the back of New York's free newspapers like the Village Voice would be full of employers looking for “playwrights.”

Who is another writer you took inspiration from in producing this book? Was it a specific book, or their whole body of work? (Can be more than one writer or book.)

I love

as a songwriter, performer, and writer. Just Kids is an important record of a magical time that paints a portrait of two artistic legends as young people. My memoir is not as iconic as hers but I like to think it is funnier because the stakes are so low.What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to publish a book like yours, who are maybe afraid, or intimidated by the process?

I spent years convinced that publishing was a straight path when, in fact, it is a crooked path.

There are so many writing coaches and experts online selling a 1-2-3 process but the process is chaotic, and no two paths are the same. The best advice I think any author can give is to refuse to hear “no.”

That doesn’t mean there aren’t obstacles when trying to get published because the business is ever-changing and frustrating and full of biases and bureaucracies. Like any industry, there are dishonest or casually cruel players. Disappointments abound. But I had an acting teacher once say, "You cannot fail forever." He was right. Now, you can fail for a long, long, long time. But he wanted me to know that sometimes, you just have to forge forward, not listen to reason or advice, just go, go, go, knock on doors, pound on doors, and find a way into the rooms you want to be in.

What do you love about writing?

I love listening to music while I write, and I love my French coffee press. I love writing during the very early hours of the day or the witching hour. There are times when writing is genuinely exciting—it makes my heart pump like I’m exploring a cave full of crystals. Sometimes, writing brings me a quiet, a calm that I find hard to replicate. My sobriety is built on living in the moment, and I write my best work when I’m in the moment, too.

What frustrates you about writing?

Talented marketers are never given their due: it is a dark art that some people are very good at doing. I was told that I would have to shoulder a great deal of my book's marketing, so I was not taken aback when that proved true, but I wish, in retrospect, that I had done more, far earlier than I thought was necessary. Live and learn. Anyway, hustling for readers is frustrating for me, specifically because I don’t think I’m good at it. It’s an insecurity that I’m trying to get over. Really effective social media strategies, for instance, require a brain that is both shrewd and creative, a unique combination.

What about writing surprises you?

When I'm doing it right, everything about writing surprises me. I always outline, for example, but sometimes, while writing, new directions and opportunities reveal themselves, new thoughts and perspectives that were hidden are uncovered. I write for the same reason I read, to be surprised — and delighted or moved or horrified. My life is the story of all the things I wasn't expecting and how I reacted to them — we are all a collection of surprises.

Does your writing practice involve any kind of routine, or writing at specific times?

I am a big believer that the only way to find your flow — that mental space where time and space melt away, and you're connected to your subconscious and just writing — is to set a timer and write. Sometimes I set that timer for 5 minutes, sometimes 15, and I write — I fill the page with words — and when the timer dings, I stop writing. Unless I have momentum, and then I keep writing, and there are times the wind is in my sail and I write for hours.

That doesn’t happen often but when it does — wow.

I love listening to music while I write, and I love my French coffee press. I love writing during the very early hours of the day or the witching hour. There are times when writing is genuinely exciting—it makes my heart pump like I’m exploring a cave full of crystals. Sometimes, writing brings me a quiet, a calm that I find hard to replicate. My sobriety is built on living in the moment, and I write my best work when I’m in the moment, too.

Do you engage in any other creative pursuits, professionally or for fun? Are there non-writing activities you consider to be “writing” or supportive of your process?

I love walking. It's one of the perks of living in an expensive, fast-paced city like New York — the walking is exceptional. I also love going to the movies. When I sobered up, I promised myself I could see any movie I wanted in a theater, and I could eat all the popcorn, and I could go by myself or with friends. This activity isn't cheap, but it's not as expensive as my drinking habit, that's for sure. So I see all kinds of movies: new ones, bad ones, classics, art house faves.

What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned, or in the works?

Oh, the dreaded “What’s next?” question, which I was first asked during the launch party the day my book came out. I answered: “Death.” Luckily, that triggered a laugh and not a long awkward silence.

There’s a part of me that feels wrung out after the release of Theatre Kids, but another part of me desperately wants to apply all that I’ve learned these past two years to a second book.

I do have a sort of new idea, a vibe, really: a romantic, political, slightly mordant, magical realist nonfiction western that explores my family’s long history in El Paso, Texas, and the controversial border itself, which is an ancient, endless stretch of desert that is neither Mexico nor the U.S., but a third place that is both haunted and hopeful. I’m researching the Conquistadores and Mexico’s war with France right now and talking to my mom about my great-granddad, who allegedly ran guns for Poncho Villa. My old man was, of course, a Lucha Libre ring announcer in fabulous/sketchy early 60s Juarez, which is where he met my bookish, chain smoking, teenage mamacita. Anyway, as I wrote, it’s all vibes for now.

John Devore is the greatest.

My son pre-ordered your book and it is on his nightstand.